Next summer, some 110 million visitors will enter America’s National Parks. Among the most enthusiastic will be the paddlers running whitewater sections of the Merced River through Yosemite. That’s because, for the first time since the invention of modern whitewater kayaks and rafts, the National Park Service is allowing them on parts of the river that offer some of the most scenic and challenging rapids anywhere in the world. The opening up of the Merced is part of a much larger project, five years in the making, that will attempt to alleviate road traffic problems, as well as roll back some of Yosemite’s early, ill-conceived development—the ice rink in the shadow of Half Dome will be moved—while allowing more access for some of the sports that have come to define modern adventure.

The , as it’s called, is a small but significant example of a transformation under way in our national parks. Last October, , Interior Secretary Sally Jewell announced an “ambitious initiative … to inspire millions of young people to play, learn, serve, and work outdoors.” Among her goals is getting ten million urban kids into the parks by 2017, a response to the country’s evolving demographics and the aging of park users. At Yosemite, the average age of visitors is 38, with the largest group between 46 and 50.

Jewell’s vision of inclusivity should be enthusiastically supported by anyone who cares about the future of our park system. I say this despite the fact that it falls well short of what we need. Because, while she has the right idea in reaching out to new communities, like her predecessors, she’s ignoring the people who are most desperate to be allowed in: the paddlers, mountain bikers, and other adventure-sports athletes who are banned from many of the nation’s best natural playgrounds. It’s an outdated stance that overlooks the role these activities now play in our relationship with wild places, and it seriously undercuts public support for an expansive and growing park system.

Since the Park Service was founded in 1916, managers have struggled to decide which activities to allow. The congressional mandate is to leave the land “unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.” “Not dented, not scratched, but unimpaired,” says Mike Finley, a former superintendent at Yosemite, Yellowstone, and several other national parks, who now heads up the , media mogul Ted Turner’s family land-conservation outfit.

Of course, “unimpaired” and “enjoyment” have always been fuzzy concepts, open to interpretation by whoever happened to be making the rules at the time. From the outset, commercial cattle grazing was grandfathered in at a number of parks. Then, in 1957, Congress approved Mission 66, an unprecedented ten-year, $700 million series of construction projects intended to improve infrastructure by building thousands of miles of roads, visitor centers, campgrounds, bathrooms, gift shops, and maintenance bays. The parks as we now know them are a reflection of this single act. In his 2007 book, , Ethan Carr, a professor of landscape architecture at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, writes that the act “came to symbolize … a willingness to sacrifice the integrity of park ecosystems for the sake of enhancing the merely superficial scenery by crowds of people in automobiles.”

As Carr notes, Mission 66 certainly opened the parks to more people, but it was widely viewed as a disgrace for the Park Service. Oddly, the backlash hasn’t so much been against cars or hotels or sprawling RV campgrounds but against recreation, which many preservationists came to see “as the primary agent of … destruction.” Officially, superintendents, who have wide latitude in determining what’s allowed in each park, weigh the impact of activities like kayaking against that “unimpaired” mandate. Unofficially, though, as Finley explains, the debate is both simpler and more philosophical: “You can’t roller-skate in the Sistine Chapel, nor should you.” Which is to say that adventure sports are banned in parks for cultural reasons.

What all this has left us with is phenomenal natural areas that are for the most part managed like drive-through museums. Meanwhile, a growing number of outdoor athletes, who should be among the most committed park stewards, have been ostracized. The nonprofit , a Washington, D.C., umbrella group for human-powered-advocacy organizations like , climbing’s , and the (IMBA), has 100,000 members and skews toward a Gen Y demographic. By comparison, the (NPCA), the historical champion of the national parks, has 500,000 members with a median age in the sixties.

“There’s a real relevancy problem with the parks,” says Adam Cramer, Outdoor Alliance’s executive director. “They’re shutting off vectors like bikes and kayaks for people to have the kinds of meaningful experiences that are the genesis for a conservation ethic.”

Indeed, many young people fall in love with wild places by playing in them. And yet, in a number of instances, park authorities have taken moves to curtail sports. Last December, Death Valley National Park , citing safety concerns for runners in the heat. And despite intervention from Colorado senator Mark Udall and governor John Hickenlooper, the USA Pro Cycling Challenge was to use roads that pass through Colorado National Monument.

“It’s a case where the paperwork hasn’t kept up with the sports,” says John Leonard, a ranger in Denali National Park, which requires guides and clients to be roped together much of the time on Mount McKinley, effectively banning guided skiing. “Out of one side of our mouth we’re saying we want millennials to come to the parks, and out of the other we have all these bureaucracies in place that make everything difficult.”

The result is that many wilderness-loving athletes find themselves opposing new public-land designations because the added protections would get them barred from areas they currently use. This dynamic was revealed starkly in 2011 when bikers and climbers sided with motorized off-roaders in near Aspen, Colorado, which would have locked out all three groups. (In the end, the IMBA and others successfully advocated for backcountry land that was bike-friendly but not open to development.)

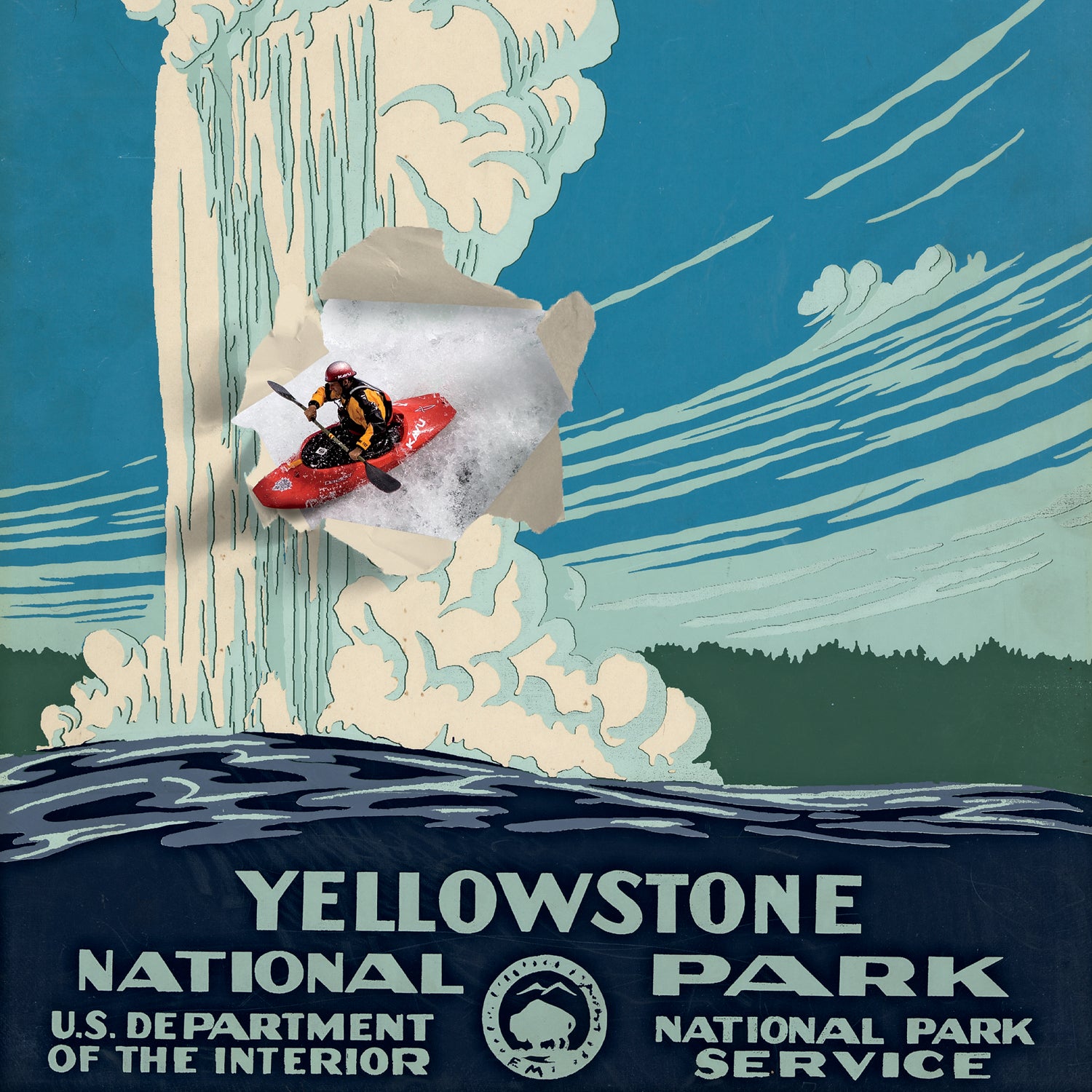

In another instance of odd bedfellows, last February Cynthia Lummis, a Republican congresswoman from Wyoming, introduced the , which would give the Park Service three years to figure out how to allow boats on Yellowstone’s waterways. In February, it passed the House of Representatives. It’s hard to say whether the bill was a politician representing her constituents or a shrewd way for a conservative to divide environmentalists, but it effectively set paddlers against the NPCA, which opposes boating on the park’s rivers.

Within the parks, much of the progress has been due to the efforts of advocacy groups. In Yosemite, long an outlier in welcoming athletes—hang gliding has been permitted since the late seventies—the Merced River Plan was championed by D.C.–based American Whitewater. In 2011, the IMBA helped convince managers at Texas’s Big Bend National Park to perform an environmental assessment and allow a comment period for the new Lone Mountain Trail.

If anyone understands the need to evolve the Park Service’s attitude toward recreation, it’s Jewell, who spent 17 years at REI before she was appointed by President Obama. So far, though, she has ignored the topic. If Jewell truly wants to build a park system that will endure, her next move should be to issue a directive for superintendents to study where and when outdoor sports might be appropriate. Nobody is demanding that bikes be allowed on every trail, that kayakers be given license to bomb every creek, or that climbers be granted blanket permission to start bolting routes. But there is room for more sports alongside the quiet reverence.

Imagine the possibilities. You could park near an entrance point, grab your bike, boat, climbing gear, or even wingsuit, and, you know, roller-skate in the Sistine Chapel. When I asked IMBA executive director Mike Van Abel what his dream trail would be, he was ready with an answer: circumnavigating Grand Teton National Park and connecting to Teton Village. Then he offered something more provocative: “There’s some real interest in winter fat biking on the roads in Yellowstone. Wouldn’t that be cool?”