On February 26, 1919, President Woodrow Wilson signed the Grand Canyon National Park Act, preserving more than 1.2 million acres of the country’s most spectacularly scenic land “as a public park for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.”

And the people have taken advantage: today��the Grand Canyon��attracts more than six��million visitors a year, exerting an almost magnetic pull on hikers, rafters, explorers, and tourists from all over the world. Artists and writers are also drawn to the canyon, hoping to capture its legendary beauty and breadth. But according to the scientist and explorer John Wesley Powell, who in 1869 led the first-recorded expedition of white men through the canyon, this may be a bootless errand. “The wonders of the Grand Canyon cannot be adequately represented in symbols of speech, nor by speech itself,” Powell wrote. “The resources of the graphic art are taxed beyond their powers in attempting to portray its features. Language and illustration combined must fail.”

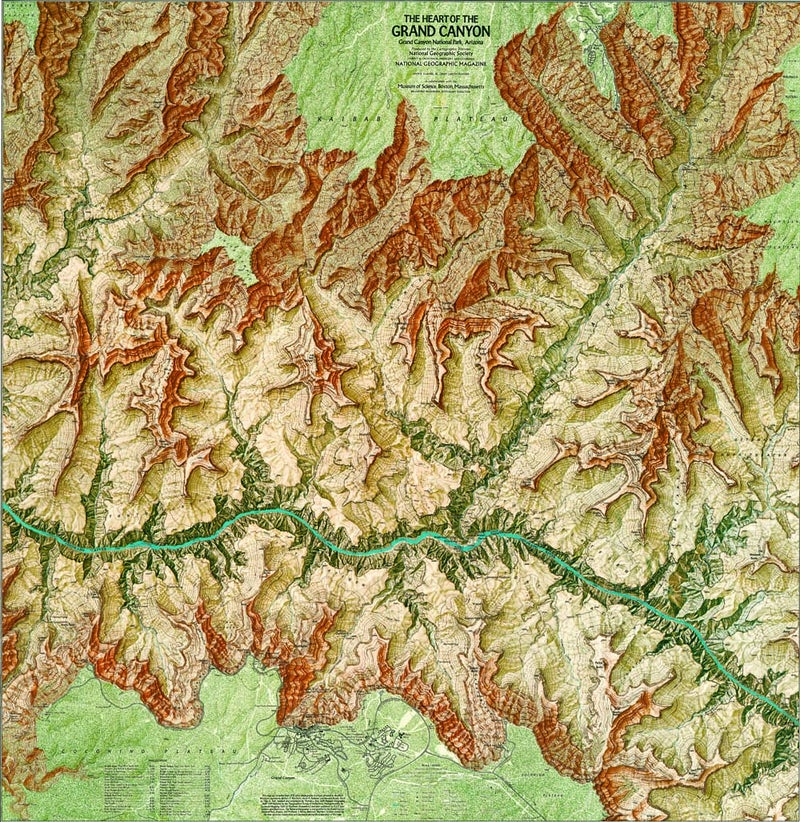

One hundred years after Powell’s famous expedition, another explorer was inspired to try to portray the canyon’s grandness through a different medium: cartography. Bradford Washburn’s map, “The Heart of the Grand Canyon,” published by National Geographic��in 1978, is still considered by many to be the most beautiful map of the area ever created.

It took eight years of planning, fieldwork, analysis, drafting, painting, and negotiating to create his map of the Grand Canyon. Such an endeavor would be unheard of in today’s digital world. “Maps are simply not made like this anymore,” writes cartographer Ken Field. “It’s the epitome of dedication and commitment to the craft of making a map.”

The story of Washburn’s map, as told in the 2018 National Geographic book , started when Washburn and his wife, Barbara, visited the Grand Canyon in 1969. They had come to acquire a boulder from the bottom of the canyon to display in front of Boston’s Museum of Science, where Washburn was the director. “We were astonished that no good large-scale map was available anywhere,” he recalled. So��he decided to make one himself.

At age 60, Washburn was a world-renowned explorer, mountaineer, and photographer with an impressive and unusual résumé. He was the first to ascend more than a dozen peaks in Alaska; he gave Amelia Earhart��advice that might have kept her from getting lost had she heeded it; and a book of his mountain photography would one day include a preface written by Ansel Adams. He had led dozens of mountain expeditions, all without any major injuries to his teams. He even once risked his life to rescue three sled dogs from a crevasse. Barbara accompanied him on many of his expeditions and became the first woman to climb the tallest mountain in North America, Alaska’s Mount McKinley (now officially called Denali).

Several of these expeditions were backed by the National Geographic Society, and one resulted in a gorgeous relief map of part of the Saint��Elias Mountains on the Alaska-Canada border. In 1939, Washburn became director of the Museum of Science, which provided a small annual research fund of $10,000. In 1970, he used that money to get started on what would become an epic project to map one of the world’s greatest natural wonders.

After a few weeks in the canyon, Washburn was convinced of the potential for “a map of really superlative beauty as well as topographic quality.”

The first order of business was to get an aerial view of the canyon. Washburn ordered complete coverage from around 26,000 feet and then again from around 16,000 feet. Photos in hand, he and Barbara headed into the canyon for the next step: setting up a survey network in the canyon and along the rim, starting with Yaki Point, which had a known elevation, latitude, and longitude recorded on a USGS��brass benchmark hammered into the rock.

Many of the points in their survey were extremely difficult or impossible to reach on foot, so Washburn hired helicopters to get them there. The Washburns and their assistants may have been the first people to ever set foot on some of the canyon’s most remote points.

Often Washburn was dropped off on top of a pinnacle or small butte��along with surveying equipment, such as a state-of-the-art laser range-finder device still under development, on loan from the company that made it. Using a built-in telescope, Washburn would aim the helium-neon laser at a reflecting prism positioned on another point miles away. The laser beam would be reflected back to the range finder, which measured how long the beam’s round-trip took and translated that into distances that were accurate to within 6/100 of an inch per mile. Washburn used a 40-pound surveying instrument called a theodolite to measure the angles between each of the control points, providing him with the relative position and height of each set of points.

After a few weeks in the canyon, Washburn was convinced of the potential for “a map of really superlative beauty as well as topographic quality.” Knowing exactly where to find the expertise, and the funds, needed to realize that potential, he asked the National Geographic Society to join the project.

The society’s archives contain hundreds of pages of correspondence about the project that reveal Washburn’s boundless enthusiasm, penchant for effusive prose, and stubborn commitment to make a map of the highest possible caliber. “The resulting map, if produced with sparkling quality, could be an exciting addition to world cartography,” he wrote in a funding proposal, “and depict one of the world’s most magnificent cartographic challenges.”

According to Washburn, it would sometimes take Swiss cartographers “more than a day of intense labor to produce a few square centimeters of cliffs.”

In 1971, Washburn got the $30,000 he’d asked for, and in return he promised, “You can count on me leaving no stone unturned to see to it that this job is beautifully executed.”

He wasn’t kidding. Over the next seven years, Washburn sweated every detail, from instructing his team on how to coax helicopter pilots into early-morning flights��to how to make the canyon’s cliffs look jagged enough on the map. Along the way, the project doubled in size, from 84 square miles��of the South Rim, the most heavily visited area in the canyon, to a 165-square-mile area that included both rims and around 90 percent of the most popular trails.

Every measurement on the ground was double- or triple-checked, with particular attention paid to trails. The Washburns measured nearly every foot of every trail at least once, if not twice, using a wheel with a circumference exactly one-thousandth of a mile. By pushing the wheel along the ground and marking their progress on a special set of aerial photos taken along each trail from around 12,000 feet, they determined the trails’ precise lengths. Not satisfied with just his own measurements, Washburn sent assistants and volunteers into the canyon to retrace his steps with very specific instructions. “If you make a bad mistake, never back up, as the wheel won’t reverse,” he wrote to one volunteer surveyor. “Just stop and cuss a reasonable amount. Then go back to where you know you made your last reliable measurement.”

By 1974, the fieldwork had entailed around a dozen trips by the Washburns that amounted to 147 days in the canyon, almost 700 helicopter landings, thousands of measured distances and angles, and around 100 miles of triple-checked trail measurements. The costs, split between National Geographic and the Museum of Science, had topped $100,000, equivalent to nearly half a million dollars today. But the hardest part was yet to come.

Turning all of this fieldwork into a map would turn out to be just as laborious and twice as complicated as gathering the data. Washburn’s goal was to produce a masterpiece, which meant putting together an all-star team to make the map. “Nothing quite like this has ever been done before,” he wrote to the president of the National Geographic Society.

To translate all the aerial surveys and field measurements into contour lines on a base map, Washburn hired a New York mapping company that he deemed “extraordinarily expert in this intricate work.” For what he considered “the most complex and challenging shaded-relief project ever attempted,” he insisted on engaging the universally acclaimed Swiss Federal Office of Topography (also known as Swisstopo). The rest would be in the hands of National Geographic’s own world-class cartography shop.

The Grand Canyon map was the largest and most time-consuming relief map Tibor Tóth, a Swiss-trained cartographer, worked on during his 22 years at National Geographic.

Washburn directed every aspect of the map’s creation and had his say on each detail. He corrected contour lines so that the sharp corners of trails lined up precisely with creek crossings, worried about what sort of line should represent ephemeral streams, and debated how much blue shading should be used in the shadows. He was particularly concerned that the canyon’s distinctive colors be captured faithfully, so he ordered yet another aerial survey, this time in color, “in order to give the cartographers a very accurate understanding, not only of the color of the rock, but also the exact extent of trees and other vegetation.”

Even then, Washburn wasn’t satisfied. He arranged for a cartographer from Switzerland and another from National Geographic to be flown to the canyon to see the colors for themselves. Internal National Geographic memos about the project reveal a sort of admiring exasperation with his determination in comments such as, “Bradford Washburn will not take no for an answer!” and “Bradford Washburn never gives up!”

The Swiss cartographers were, and still are, unrivaled in their ability to give mountains and cliff faces the illusion of three dimensions with a technique known as hachuring, which involves drawing short, precise lines in the direction of the slope. According to Washburn, it would sometimes take them “more than a day of intense labor to produce a few square centimeters of cliffs.” To date, cartographers have been unable to top the handiwork of the Swiss.

“I think everyone would agree that the manual rock hachuring that you see on Washburn’s map, and other maps made by Swisstopo, is just wonderful,” says Tom Patterson, a cartographer for the National Park Service whose own work mapping the canyon has been inspired by Washburn’s map. “It’s basically state-of-the art and hasn’t been replicated by digital tools.”

National Geographic’s��Swiss-trained cartographer, Tibor Tóth, painted the relief shading onto the map. The Grand Canyon map was the largest and most time-consuming relief map Tóth worked on during his 22 years at National Geographic. By his account, it took 1,074.5 hours to paint it.

In the end, all that work paid off exactly as Washburn hoped: the map is exceptional, both technically and aesthetically. National Geographic produced two versions of “The Heart of the Grand Canyon” map, one at the full 33-by-34-inch size��and another covering slightly less territory as a supplement to the July 1978 issue of National Geographic magazine, putting it in the hands of more than ten��million readers around the world.

Today��this sort of arduous, time-intensive data collection has been largely supplanted by GPS technology. But the artistry of the map has arguably not been surpassed. “Washburn’s ‘Heart of the Grand Canyon’��map is still the gold standard for Grand Canyon mapping today,” Patterson says.

This article has been adapted from , published in October 2018.