FROM THE TOP of a 164-foot-tall metal shaft perched on the small Danish island of Samsø, the wind can just about suck the eyelashes off your face.

Samsø, Denmark

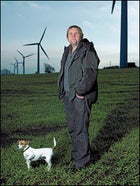

Dairy, pumpkin, and wind farmer Jørgen Tranberg, with his dog, Vaks

Dairy, pumpkin, and wind farmer Jørgen Tranberg, with his dog, VaksSamsø, Denmark

Erik Andersen and friend

Erik Andersen and friendSamsø, Denmark

The road to Langør, on Samsø's east coast

The road to Langør, on Samsø's east coastSamsø, Denmark

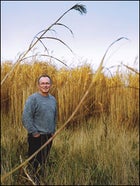

Søren Hermansen in a field of elephant grass, an energy crop

Søren Hermansen in a field of elephant grass, an energy cropSamsø, Denmark

Green-powered homes in Langør

Green-powered homes in LangørAfter climbing 140 ladder rungs, I’m gripping the railing inside the vibrating engine room, a bread-truck-size space at the tippy-top of a windmill that holds a series of gyrating generators. At the press of a button, the ceiling peels away, James Bond style, to reveal a cloudless sky, interrupted only by the regular rotations of three sleek, white, 88-foot-long blades.

The humming platform feels and sounds like a jet about to lift off, but all the kinetic energy ends up beside me in the ten-ton gearboxthere and in my hair. It’s exhilarating, like riding a Harley through a hurricane. I’m almost tempted to burst into a Springsteen song. What I’m feeling at the base of my spine is the prevalent weather pattern roiling in from the North and Baltic seas: 20-mile-per-hour winds being converted into 463 kilowatts of electricity, enough to power more than 600 households this very moment.

And the view’s nice, too.

I see the expanses of productive corn and pumpkin fields, the Ben & Jerryesque cows munching local silage among the sunflowers, the bike lanes, the sensible traffic flow, the traditional timber-frame and brick houses, including the one belonging to the proud farmer who owns this turbine. It’s enough to make a New Urbanist weep. From up here, Samsøa dollop of land some 12 miles off the nation’s main peninsulalooks like a marvel of social and natural engineering. To the south of me stand two more windmills; to the northeast, eight more, like pins on a military map, and about two miles offshore is a necklace of an additional ten.

The land turbines provide enough electricity for the entire Nantucket-size island of about 4,200 people. The clean power generated by the offshore turbines is just gravy; sold to the mainland, it more than atones for the amount of carbon dioxide that Samsø pumps into the air due to its use of “dirty energy” like petroleum, which fuels its cars and some home furnaces. In fact, Samsø has spent the past decade becoming an eco-wonderland, setting up wind, solar, biofuels, and other renewable technologies to satisfy its energy needs. The island has even gone beyond “carbon neutrality,” the cherished environmental goal of zeroing out the production of CO2, the greenhouse gas most responsible for global warming.

Now, in addition to its renown as a land of new potatoes, Samsø enjoys the distinction of being the most carbon-negative settlement of its size on earth.

IT’S A RELIEF TO BE ON THE GREEN ISLE, a CO2-safe zone where, for once, my everyday habits won’t add to climate change. I’ve come to Denmark determined to be an ultra-low-carbon traveler, but I spent my first few days in Copenhagen, where I really had to work at it. I rode a Dahon folding bike all over the place and calculated the CO2 output of every mile of public transport so I’d know how many trees to plant or clean-energy credits to buy when I got back home, to make up for my carbon transgressions. In the biggest sacrifice, I spent three nights sleeping in one room with 33 other people at the Sleep-in Green hostel in Copenhagen. I took to calling it the Can’t-Sleep-in Green. So what if the bunk beds squeaked and the girls from Texas donned their boots at five in the morning (and left large canisters of hair products that simply would not sort into any of the dazzling array of recycling bins)? It was great for my planetary balance sheet: solar electricity, organic juices, energy-efficient lightbulbs, and minimal waste.

To get with the program even more, I sought tips from a local carbon guru, Bente Hessellund Andersen, who’s known for her polite climate harangues directed at non-green European leaders. A longtime environmentalist, she’s neat and pretty, a soccer mom without the SUV. She doesn’t even own a car. “I feel sad when young people tell me they need to have a carvery sadsince it’s their kids who’ll suffer from global warming,” she told me during a torrential rainstorm at a bar near Tivoli Gardens. We were both sopping wet, having arrived, naturally, by bicycle.

Each Dane produces on average 13 tons of carbon dioxide per year, Andersen said. (She herself produces less than that.) Each American produces about 20. “We call it ‘the American lifestyle’ when we eat a lot of meat,” she said, and proceeded to explain the golden rules of a low-carbon life, ticking off a list that made McDonald’s look like the seventh ring of hell: Eat vegetarian, locally grown foods, preferably organic, because they require less gasoline to transport and fewer fossil-fuel-laden pesticides and fertilizers. If you’re really feeling zealous, eat your food cold, or, if you need it hot, keep a lid on the pot. “And as a tourist, buy locally made goods,” she added. I don’t think she had in mind my latest souvenir: a gel-filled plastic pen with a floating Viking ship inside.

But the biggest carbon spewers, Andersen went on, are transportation and housing. Together they contribute 60 to 80 percent of a person’s CO2 footprint. I was off the hook with my carrot slaw consumption and with the hostel and the bike, but the planes and trains I’d taken had done some damage. Andersen referred me to some Web-based carbon calculators to figure out my transportation debt and told me to consult a report about food-associated CO2 emissions, appetizingly called “Eating Oil.” It might help me assess how many greenhouse gases were released to make my $12 lime-drenched mojito the other night at a restaurant called Pussy Galore’s Flying Circus. I should have had an aquavit.

On Samsø, though, I could stop tallying and relax. Some islands feel magical because of healing waters or succulent fruits. Samsø’s aura comes from the fetching way the islanders crunch their numbers to achieve the great Kyoto-driven concept known as offsets. Here’s how it works: If you use dirty power, which most of us must, you just have to make up for it. Islands, nations, or citizens can take steps like planting thousands of trees to cancel out the carbon dioxide they’ve added to the atmosphere. They can also produce clean energy for others to use, thereby preventing additional emissions of greenhouse gases. With enough of these measures, it’s possibleon paper, anywayto become carbon neutral or even carbon negative. Samsø’s wind turbines, for example, produce about 105 million kilowatt-hours of electricity per year, but the island needs only a quarter of that, leaving a surplus of 77 million kilowatt-hours, which enters Denmark’s main power grid. Meanwhile, Samsø’s petroleum-fueled transportation sector uses the equivalent of just 53 million kilowatt-hours per year, so the islanders figure they’re still in the cosmic clear with room to spare.

The bottom line: Samsø is 140 percent carbon negative, while virtually the rest of the universeexcept for off-the-grid pockets in a few communities and the solar-powered International Space Stationis carbon positive to the tune of adding 27 billion metric tons of CO2 to the atmosphere each year. (Afghanistan and Chad are among the nations with the lowest per-capita carbon emissions; the U.S. releases the most overallnearly one-quarter of the planet’s total.)

Someday, Samsø hopes to use its surplus power to make hydrogen or charge lithium-ion batteries to run its cars. In the meantime, I can thumb a teeny car ride (three miles) in the rain. It’s offset! I eat a thick slice of beef at a smorgasbord. Even though the meat probably originated in Argentina, I am guilt-free. Samsø’s clean power flowing into the Denmark grid means some coal plant doesn’t have to produce the wattage. Sorry, Bente. Please pass the roast.

JØRGEN TRANBERG IS A GAP-TOOTHED dairy and pumpkin farmer. His latest crop is the one-megawatt turbine I climbed. When I first meet him, he’s trying to U-turn a tractor carrying a huge bale of hay. “I’m not an environmentalist,” he says, flicking ash off his cigarette. “It’s a business venture.” Down the driveway sits his new Drago Fiesta motorboat, so I’m not surprised when he tells me business is good.

Almost everyone on Samsø, in one way or another, makes money from wind. Turbines are owned by private investors like Tranberg, by the government, or by cooperatives of people who bought shares to finance their construction. The process is democratic in the way so many things are in Denmark; shares cost about $360 each.

Tranberg, for his part, took out a loan to buy his $1 million windmill six years ago,

The fairy tale of turning pumpkins into turbines is one told frequently on the isle, most notably in the Ecomuseum in the main town of Tranebjerg. There, among the Viking coins and the potato-shaped chocolate bonbons in the gift shop, are posters that explain the history of the Samsø experiment: how in 1997 the green-leaning government and the Danish Energy Agency launched a contest to select the island with the best plan to become energy-sustainable by 2008; how Samsø won and has since spent $70 million on the project; and how European grants also helped subsidize the effort.

The result has been fairly staggering. Between 1997 and 2005, Samsø is estimated to have reduced emissions of global-warming pollutants like carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide, and nitrous oxide by 142, 71, and 41 percent, respectively. Today, 100 percent of islanders use green electricity, and 70 percent of residences are heated by wind, solar, or biomass systems, including huge, centrally located furnaces that burn straw. Straw is considered carbon neutral because it’s a by-product of crops like alfalfa that help absorb CO2 from the atmosphere, just as trees do. The straw is burned in super-hot, super-efficient kilns. Plus the ash is collected and spread back on the fields to fertilize the next cycle. The cows eat the alfalfa, make some damn fine milk, and then the straw goes off to the furnace.

It’s so Scandinavian.

I’m staying down the road a few miles with another dairy farmer, Erik Andersen, and his wife, Lise, in the tiny town of Besser. Now in their sixties, they live with their Border collie, Jacko, in a beautiful, simple stucco house. Andersen, who has milked cows all his life, caught the renewables bug in a big way after Samsø won the energy contest. He installed 18 square yards of solar paneling on his barn roof, supplying all his electricity and most of his heat and hot water from April to October. The rest of the year he chops scrap wood from his land to feed his biomass furnace. He’s also taken to growing rapeseed, otherwise known as canola, for home-brewed biodiesel.

After serving me aeblekage, a baked apple cake with otherworldly good fresh cream, Andersen shows off his voltage meter. “I like to come out and watch the meter running backwards,” he says. He is tall and lumbering and sports a gray buzz cut. Every day he wears overalls and irrigation boots, and he is not a man of many words. “It is interesting to make your own energy,” he says.

Next he takes me out to the garage to see his prized new possession: a rapeseed press. The black, beady seeds funnel into the machine, which squeezes the bejeepers out of them. One spout kicks out a narrow cylindrical green mash, the by-product cake, while another spout pours a wan, yellowish oil. Andersen feeds the nutritious mash to his cows so he doesn’t have to import soy-based feed. He then filters and pours the oil right into his two tractors and his red Volkswagen Passat. No refining, no cleaning, no mixing with lye or other chemicals.

“What are we going to do when the oil runs out? You need to prepare,” he says. By not buying petrol, which costs $6.38 per gallon here, he figures he’s satisfying his independent streak.

“Try it,” he says, grinning. He wants me to eat his gasoline. Fine. I pour some onto my finger and take a taste. It’s nicelight and bland, kind of like oil and salad at the same time.

I’M NOT THE ONLY ENERGY TOURIST on Samsø. Some 2,000 turbine peepers visit the place every year. The island has become a training ground for experts from Thailand, China, Europe, and America, including a group from the University of Virginia. Demand is so great that the town government is helping build a conference center (out of sustainable materials and in the shape of a Viking longhouse) to accommodate the eco-wonks who want to glean the island’s secrets.

The week I’m here, so is a delegation from Ireland

If this is the Fantasy Island of the greenie set, then Hermansen is its Ricardo Montalban. Instead of white suits, though, he wears denim, and it’s not hard to picture him in one of those Norse helmets with horns. His ancestors probably wore them, because his family has lived on Samsø for at least ten generations. Part miracle worker, part gracious host, he directs the European Unionbacked Samsø Energy Office and has been with the renewable-energy project since its beginning. A part-time rock musicianhe plays bass in a band called, fittingly, the GeneratorsHermansen has earned the public trust over nearly a decade of meetings, tours, and ribbon-cutting ceremonies.

In addition to orchestrating the development of Samsø’s centralized heating plants, which efficiently warm 1,000 residences, he convinced hundreds of retirees to put government-subsidized renewable-energy systems in their homes. In the meantime, among other projects, he’s shepherding farmers into a rapeseed-growing cooperative and overseeing a grant from the EU to install a hydrogen-production test facility to power vehicles. Hermansen is determined to extend the green dream to transportation, the one dirty sector left. “The vision is that all the gas stations on the island would pump plant oil,” he says.

After a day, the Irish delegates are awed. “These lads here are light-years ahead of us,” says Eugene Houlihan, who works for a building-supplies cooperative in Inis Oírr. He shakes his fair head. “We don’t have a clue. Cheesus. So we’re here to learn how to apply it,” he says. “We are ashamed to listen to the Danes. Cheesus.”

Well, hey, I point out as we sit in a pub overlooking the picturesque harbor, at least Ireland signed the Kyoto agreement. America can’t even accept a cap on greenhouse-gas emissions. “True,” he says, brightening. But then Anthony McCarthy, an energy consultant from County Wexford, pipes in: “If Americans get serious about alternative energy, they will fucking pass everybody.” He peers deep into his Carlsberg. “That is the beauty of America.”

AFTER THEY WERE DONE INVADING the civilizations of Northern Europe, the industrious Danes turned to building great ships, first out of wood, then steel. Now they employ a similar metal-and-rivet fabrication method to make windmills for Vestas, one of the largest turbine manufacturers in the world. This, after all, is also the birthplace of Lego; Danes are organized, rational, and easily assembled. The highest earners pay about a 60 percent income tax, and what they get in return is free universities, free medical care, and some really good, cheap cheese.

But how did Danes get to be so carbon goody-goody? In Copenhagen, I ask the man who should know: Lego chairman Mads øvlisen, who also serves on the United Nations’ newly created Global Compact Board and drives an electric Citroën to work. After an eloquent briefing on the Vikings”Danes believe they can change the world, and, therefore, they must!”øvlisen tells me that Denmark’s ability to look outward stems from its seafaring past. That, and its tradition of social equity, made sustainability highly desirable. “We are a tribal country,” he says. “And that drives innovation and adaptation.”

Geopolitics also played a part. In 1973, OPEC imposed an oil embargo against the U.S. and the Netherlands for supporting Israel’s war against Syria and Egypt, and nearly quadrupled the price of petroleum for everyone else. The U.S. at the time imported about 35 percent of its oil; Denmark imported more than 90 percent. Keenly aware of their vulnerability, the Danes spent the next 30 years figuring out how to secure an energy-independent future, all without nuclear power, which parliament outlawed in 1982.

Now, remarkably, Denmark is about 150 percent self-sufficient. A net exporter of energymost of it oil and natural gas from the North Seait also sells wind power to it neighbors.

The American response to the embargo, by comparison, was more of a cheap-oil-is-our-birthright hissy fit. In the late 1970s and early ’80s, to be fair, the U.S. launched some serious alternative-energy schemes, complete with tax credits and federal funding for renewables, and for a brief moment California actually became the king of wind power. Then, during the Reagan era, federal and state subsidies expired, making it impossible for wind and solar to compete with oil and coal. Today, the U.S. imports nearly double the oil that it did in 1973or about 60 percent of what it consumes. Wind power makes up less than 1 percent of the American electricity pie.

We can turn this around if we choose to, observers note. “This country is capable of sleeping for a long time,” says former CIA chief James Woolsey, now an eco-minded energy-security specialist and vice president of Booz Allen Hamilton, a Virginia-based international consulting firm. “But when it wakes up, things move pretty fast, and that’s what we’re going to be seeing in the next few years, with a growing coalition of tree huggers, do-gooders, cheap hawks, evangelicals, venture capitalists, and Willie Nelson. Renewable-energy technologies,” Woolsey adds, “can come faster than people realize.”

Indeed, in western Indiana, of all places, there’s a mini Samsø rising from the cornfields: Reynolds, population 550, is constructing a $9.5 million power plant to turn hog manure and other ag products into clean energy. Elsewhere, at least 333 mayors representing more than 54 million Americans have pledged to follow the Kyoto mandates for reducing greenhouse gases, without waiting for Washington.

But renewables like wind power still face some Hummer-size hurdles. “In the U.S.,” says environmentalist Frances Beinecke, president of the Natural Resources Defense Council, “people still see wind power as futuristic and marginal.” To that list, one could also add “ugly”: a proposed wind farm off Nantucket, for example, faces strong opposition from locals who don’t want turbines marring the view.

“Today we can point to Denmark and say, ‘Hey, a Western country gets one-fifth of its electricity from wind.’ It’s doable,” Beinecke says. “There’s just a cultural divide we have to cross.”

MY LAST DAY ON SAMSØ, I ride my bike around the island. With its waving grasses and gentle surf, I can see why Valdemar the Victorious gave the place to his new queen as a post-nup gift in 1214. Today, goats are grazing contentedly under the photovoltaic array at a solar heating plant. I walk through some sunflowers to visit farmers who raise organic pigs and perfect cherry tomatoes. Leaving for the mainland, the ferry passes a chain of windmills, their graceful arms performing an unsynchronized water ballet.

All too soon, I’m back in carbon-positive Copenhagen. My own CO2 balance sheet is, regrettably, back in play. I’m going to be more than two carbon tons in the red, according to eco-entrepreneur Shea Gunther, cofounder of Renewable Choice Energy, a Boulder, Coloradobased firm that, for about $65, will buy U.S. wind power to offset my trip for me. (The final tally: My 10,740-mile round-trip flight from Seattle to Copenhagen, plus airport commutes, created 4,315 pounds of CO2; my train trips made 50 pounds; and my laptop and cell phone set me back nine. And that’s not even including the mojito.) So for my last night in Denmark, I really should return to the infernally correct Don’t-Even-Think-About-Catching-Sleep-in Green.

But I just can’t bring myself to face 66 other eyeballs in my room. My days in Samsø were too full of guilt-free delights and what the Danish call hygge, or coziness. I get to the city after dark. It’s late and I’m hungry. I start bicycling toward the hostel but pass a charmingly weird lodge called the Hotel Kong Arthur. Its flagrantly inefficient incandescent lightbulbs emit a friendly, warm glow. There’s a suit of armor by the entrance and soft upholstery decorated with fleurs-de-lis. How can I resist? I can’t. It includes a free breakfast! And a private bathroom!

I rant to myself that this is exactly why governments should step in and support responsible energy development: so that wayward, flawed sybarites such as myself don’t have to make endless, irksome daily decisions when all we really want is a warm bed and a bowl of muesli. With a side of bacon. And a mug of hot imported coffee. Ja.