TO TRULY UNDERSTAND ANY TRAGEDY in the wild and its power to deliver pain over decades, you have to start at the beginning. In the case of the Sespe flood, you have to go back to January 1969, when rainstorms drowned Southern California’s Ventura County under so much water that Walter Cronkite ran footage of the devastation on the CBS Evening News. The downpour began Saturday, January 18, and almost immediately the Ventura County Sheriff’s Department sent search-and-rescue teams into the Los Padres National Forest, about 100 miles northwest of Los Angeles, where on any given weekend there could be thousands of visitors. Many drove in to campsites via a dirt road that snaked back and forth across Sespe Creek, which carves its way through 50 miles of steep canyons and sharp switchbacks. When the road got wet, it swiftly turned into an impassable bog.

Sespe Wilderness Tragedy

Pat Larson holding a photo of husband Chester

Pat Larson holding a photo of husband ChesterSespe Wilderness Tragedy

Steve Larson at the site of the Sespe Creek accident

Steve Larson at the site of the Sespe Creek accidentSespe Wilderness Tragedy

Sespe Wilderness Tragedy

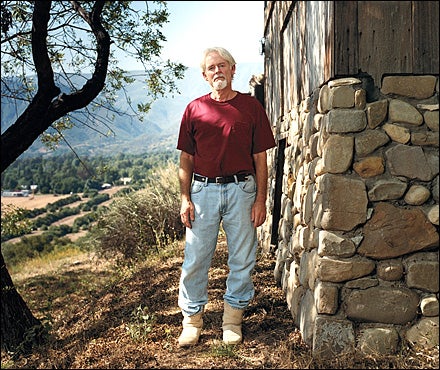

Scott Eckersley at his home in Ojai, California

Scott Eckersley at his home in Ojai, CaliforniaOn Monday morning, January 20, the Ventura County Sheriff’s Department received a phone call. The caller said that six young boys from the Canoga Park area, on the edges of Los Angeles, and their chaperone, Robert Samples, had been camping along the Sespe over the weekend and were overdue. The caller thought they were probably somewhere near Sespe Hot Springs, a popular destination about 15 miles away from Lion Camp, the trailhead where the creek road began.

Deputy Sheriff Gary Creagle was dispatched to Lion Camp and reported back that the Sespe, normally less than a foot deep, was now running more than five feet deep at the first crossing. It might be days before any vehicles could get into the area by road, and the weather prevented flying. The sheriff’s department put in a radio call to Deputy Sheriff Chester Larson, up in Lockwood Valley, just north of the area. Could he get down to the U.S. Navy’s Rose Valley Seabee Training Center, which maintained the Sespe access road as part of its combat-construction training program, and help Creagle out?

Larson was 34, with a lean face and a tight buzz cut. He’d met his wife, Pat, in the acrid oil town of Taft, over the mountains in the San Joaquin Valley. After he was nearly killed in a well explosion, he applied in 1964 to the Ventura County Sheriff’s Department, determined to build a better life for himself and his young wife. From the moment he made deputy, he had his eye on the Lockwood Valley post, which offered independence and hundreds of miles of beautiful backcountry to patrol. By early 1967, he and Pat were moving their six-year-old son, Mark, and their newborn, Steve, into the small gray house that came with the job. “Lockwood Valley was just right,” says Pat, now 68 and living quietly in a lakeside resort community two hours from Sacramento. “But his job came first. We came second. That’s how it had to be, and we accepted that.”

Larson got the call to help Creagle just after lunch that rainy Monday. He put on his slicker, donned a yellow helmet outfitted with a miner’s lamp, and paused in the door, as he always did, to tell Pat he loved her. Then he disappeared into the rain, his German shepherd, Duke, at his heels.

When he arrived at the Rose Valley base that afternoon, Larson suggested that a rescue party could get to the missing campers on one of the big bulldozers the Seabees had at the base. The International Harvester TD-20B was a monster, a staple of construction efforts in Vietnam; it weighed 15.5 tons. If anything could work its way down the muddy road along Sespe Creek and navigate its flooded crossings, it was this enormous machine. Chief Equipment Officer Robert Sears, 41, who’d been posted to Rose Valley after being badly wounded in Vietnam, volunteered to drive. Thirty-six-year-old Forest Service ranger James Greenhill, a Paul Bunyan of a man who knew the area intimately, also hopped on board. Larson left Duke in his truck and climbed up onto the growling machine.

ALMOST 40 YEARS LATER, I’m standing knee-deep in the cool water of Sespe Creek. It’s a transcendent, peaceful stream, and Steve Larson, now 41 years old and a public-school teacher from Sacramento, and I have been camping alongside it for a couple of days in June, with temperatures nudging 100 degrees. We’ve dumped our packs to relax near one of the many places where the trail crosses the creek, as we work our way back toward civilization.

This isn’t just any crossing, though. This is the place where, in January 1969, the Sespe killed Deputy Sheriff Chester Larson, Steve’s father. It also killed three other men and the six young boys they were trying to evacuate from the area. “It probably happened right about here,” I call to Steve from the middle of the river, where it deepens ever so slightly.

Steve doesn’t answer. He’s still on the bank, subdued by the weight of the past. He was just two years old when his father was killed, and after the tragedy he began to speak with a stutter. He was never told the details of the accident, only over and over that his father had died a hero. As he grew up, he was determined to escape the ghosts in his family. At 19, he went off to Chico State. There, he met Marcie, and they married in 1994. Now they live together with their two young children, Sarah and Owen, in Sacramento, where he’s been teaching for ten years. But a few years ago, just past the age his father died, Steve realized he needed to find out exactly what happened on the Sespe and what kind of man Chester Larson really had beenÔÇöand how the rescue his father attempted had ended in so much death.

After a while, Steve wades in and starts to wander alone among the dark boulders. The malign potential of the creek is hard to grasp. In fact, the only hint that the Sespe is capable of violence is the flood debris that necklaces the trees lining its banks. This is the first time he’s ever been here.

Every year, people fall off rock faces, drown in rivers and lakes, succumb to exposure, and are broken or suffocated by avalanches. You almost never hear about these tragedies, unless they happen on Mount Everest or catch the attention of the cable-news beast. But these invisible disasters are searing nonetheless. They almost always involve moments of nobility and courage and heartbreaking miscalculation. They snuff out promising lives and heap sadness, guilt, and unanswered questions on the families and friends left behind. Nature unleashedÔÇöa howling storm, a flash flood, a blizzardÔÇöhas elements of divinity and drama that expose perfectly the frailty and flaws of human nature.

What’s the half-life of tragedy in the wild? In the case of the Sespe, I discover, the pain still runs hot through the lives of everyone involved. Steve is struggling over his feelings about the father he never knew. The families who lost children still experience a corrosive legacy of sorrow and anger. And the lone survivor of the accident continues to battle the agonizing sense that he somehow could have done more.

“It’s like cancer. We have cancer,” says Debra Cassol, 57, who was 18 when the Sespe killed her two younger brothers, Bobby and Ronny. “Sometimes we get a little remission and we’re not so sick. But then it always comes back. It always comes back.”

UNBEKNOWNST TO DEPUTY Sheriff Larson and the rescue party, Robert Samples, 42, and the six boys he’d taken out for a weekend of campingÔÇöBobby and Ronny Cassol, ages 14 and 12, Danny and Eddie Salisbury, 13 and 11, Frank Donato, 13, and Frank Rauh, 14ÔÇöwere safe from the storm in a cabin on a grassy plateau called Coltrell Flat, near the Sespe. With them was Scott Eckersley, 28, an experienced outdoorsman who taught at the Live Oak School, in nearby Ojai.

Eckersley had first seen Samples’s group at Sespe Hot Springs on Saturday when the rain started. He’d left immediately, in his converted 1953 GMC refrigerator truck, and gotten bogged down on a ridge overlooking the flat, a few miles along the road from the hot springs. Samples and the boys, who’d been target= shooting, left a little later in Samples’s 4×4 Dodge Power Wagon. They got stuck, too, on the ridge opposite Eckersley. Three of the boys had made their way to the Bear Creek campsite, ten miles upstream, where they were supposed to alert park rangers and wait. But they apparently didn’t find any rangers. Worried about their friends, they loaded up on supplies from the camper shell Samples had dropped there and hiked all the way back to Coltrell Flat on Sunday, barely managing some of the fast-moving crossings.

By then Eckersley had hooked up with Samples and the remaining boys to see if he could help. With the rain continuing to pour down, Eckersley suggested they break into the cabin for shelter. By Monday evening they were holed up together, burning wooden chairs to keep cozy, eating stew made from some quail Eckersley had shot, and warming to their outdoor adventure.

Eckersley figured they would wait the rain out. But as he was washing up after dinner, he heard a low rumble and then the gnash of gears. Samples grabbed a flashlight and ran outside waving it. A few minutes later, an enormous bulldozer manned by Sears, Larson, and Greenhill pulled up. Sears hopped down and carried a big box of rations into the cabin. The boys swarmed around, digging into crackers, candy bars, peanut butter, and other treats. One asked whether they were all going to ride on the bulldozer to get out. “No,” Larson answered, firmly. “We’re going to walk out.” The only time everyone would climb up on the machine would be for the creek crossings.

It was now past 7 p.m., raining harder than ever, and getting cold. The boys had no raingear to speak of and only tennis shoes on their feet. Twelve and a half miles, with multiple crossings, lay between Coltrell Flat and the safety of Lion Camp. It was hard to imagine leaving the warmth of the cabin for the horrific conditions outside. But when the boys were told their parents would be waiting for them at the other end, everyone was eager to get going.

Eckersley, however, wasn’t convinced. They had enough food. Why not wait until morning or until the rain stopped? Larson and Sears were determined to leave right away. There was another storm coming, they said. The bulldozer had gotten them in and it would get them all out. Eckersley grabbed his pack, and the group started the long march.

It was worse than Eckersley had imagined. Everyone was soaked and getting colder by the minute. The mud was like glue. At the top of the first ridge, Larson, who had a radio, made contact with the sheriff’s department. It was 8:12 p.m., and through the crackle Larson managed to report that he was on his way out with the group. The sheriff’s department passed word to Frank Donato Sr., father of camper Frank Jr., and the local newspaper. The next morning, Tuesday, the Ventura County Star-Free Press carried the headline MISSING HIKERS SAFE.

They were far from safe, though. Four hours and multiple crossings later, the road juked into the Sespe Creek one more time. It started like every other crossing. Eckersley and Larson swung up behind Sears, who was driving, and Samples, who’d sprained his ankle. One of the boys was next to Eckersley, another was squeezed between Sears and Samples, and Samples had young Eddie Salisbury, a quiet boy with blond hair and blue eyes, on his lap. The three remaining boys found places near Eckersley, and Greenhill was up front with his light holding on to the exhaust stack. Angling slightly upstream, the big dozer rumbled into the creek. The water rose quickly to the tops of the treads, and everyone numbly waited for the machine to start its climb to the opposite bank. But instead of getting shallower, the water suddenly got deeper, and the big blade up front started deflecting water up onto the engine hood.

For the first time, Eckersley felt a stab of panic. If the bulldozer didn’t hit the other bank quickly, it would likely stall. He had barely formed the thought when the growling engine quit and a new noise rose. It was the freight-train roar of the flooding Sespe.

JAN AND DEBRA CASSOL have moved a long way from Southern California in the 39 years since the Sespe tragedy, and their neighborhood in Trafford, Pennsylvania, is high above any flood zones. Debra Cassol is a careworn woman with brown hair and a kind face. Her mother, Jan, is petite, with close-cropped red hair and sharp features. We sit down at their dining table, and Debra and Jan start to tell me about the boys. Ronny, at 12, was the clown, a natural-born mimic who used to distract Jan with his wicked imitation of her attempts to discipline the kids. Bobby, 14, was the thoughtful one, outgoing, charming, and into everything from skateboarding and track to camping and fishing. He was always looking out for Jan, Ronny, and Debra, even though she was four years older. Mostly, he and Ronny stuck close together, partners in crime, and they loved the outdoors. A camping trip with Bob SamplesÔÇöa close family friend whose sister was Jan’s work supervisor at a local hospitalÔÇöwas nothing out of the ordinary.

The last time Debra and Jan saw the boys was Friday afternoon, January 17, 1969. Both boys had been given new .22 rifles for Christmas, and they were thrilled at the prospect of a weekend of camping and target= shooting. Samples had checked with the weather service and had been told that a beautiful few days lay ahead. The boys threw all their gear into the trunk of Jan’s Lincoln Continental and piled into the backseat for the ride to the Samples house, just a few minutes away. Debra jumped into the front passenger seat. When they arrived, the boys hopped out and rooted around in the trunk for their gear. Loaded up, they paused to say goodbye. As they did, Debra felt a sudden sickness radiating through her chest. “I knew they weren’t coming back,” she says, her voice cracking. “I couldn’t tell you a flood was going to happen. All I knew was that I was never going to see them again.”

Meanwhile, Pat Larson was used to her husband disappearing into the Los Padres National Forest. He was responsible for a large patch of rugged wilderness, and when it rained there were always people needing help. She remembers the rain well, falling heavily through that January weekend and into Monday. But it was rare that Chet (as she called him) was away this long without getting in touch. The two-way radioÔÇöwhich the sheriff’s department down in Ventura used to contact her husbandÔÇöcrackled in the background.

Some radio chatter caught her attention. Two deputies were talking about an accident. She heard them say there was a survivor. They didn’t mention any names or where the accident had taken place, but Pat somehow knew this was a conversation about her life. She wandered into her bedroom and got down on her knees to pray. She and her husband were devout Baptists, regulars at the Community Baptist Church of Frazier Park. She opened her Bible to a random page and started to read. It was Isaiah 9:2. Her eyes scanned the words:

The people that walked in darkness have seen a great light; they that dwell in the land of the shadow of death, upon them hath the light shined…

And somehow she knew her husband wasn’t coming home. The words made perfect sense to her. “He was calling them to the light,” Pat says now. “I read that and accepted the fact that he was gone before I even heard about it.”

“CAN YOU START IT AGAIN?” someone shouts at Chief Sears. “No,” he says in despair. The full pressure of the icy, rising water is now ripping at everyone on the bulldozer. Greenhill’s light disappears as he wraps himself around the exhaust stack. Darkness falls over the group, except for the focused cone of light from Larson’s headlamp. The boys are mostly silent. Every ounce of strength and willpower is needed to resist the deadly pull of the water.

Chief Sears is the first to let go. He is a small man, weakened by his injuries in Vietnam, and he is spent. “I can’t hold on, I can’t hold on,” he screams. Then, “I’m going, I’m going,” as he’s washed off the back of the bulldozer. Larson turns his headlamp toward him. Everyone watches helplessly as Sears swirls in circles, trapped by an eddy created by the bulldozer. Then Sespe Creek swallows him. He is gone.

The water is rising quickly around the bulldozer. One of the boys asks if they are going to die. No one responds. In the midst of all the chaos, a child’s voice suddenly calls out. One of the boys has made his way next to Sears’s seat, in front of Eckersley. He has an arm around another boy, and he is calm. He wants to convey something important to the group. “I love you dearly,” he announces.

The words stun Eckersley. He can’t believe that a young boy, facing death, has the maturity and courage to voice such a simple and profound message. The words shock Larson, too, and he turns to see who spoke. His headlamp falls on the boy’s face, spotlighting it in the dark. Two wide eyes stare steadily back.

One by one the boys are swept away into the raging current. Every time Larson’s headlamp sweeps over the group, like a lighthouse beacon, another child seems to be missing. Samples is devastated. “We were safe in that cabin,” he says, almost to himself. Soon after, a big bush smashes against him. He lets out a cry as he and the boy he’s holding are ripped away.

Over the course of half an hour, the river methodically takes everyone except Larson and Eckersley. They are now two strangers facing death together. Eckersley desperately keeps looking for a way to cheat fate. He has looped his backpack strap over a hard point to help anchor himself, and he starts to strip off his coat, wristwatch, and shoes. Anything to help him survive the imminent swim. Larson does the same. Eckersley says he is going to pick his moment and jump, but he doesn’t. He doesn’t have the willpower.

Larson pulls his gun from its holster and fires two or three shots into the air, aiming upstream as if trying to wound the murderous river rushing at them. He says to Eckersley that there may be some rescuers within earshot. It’s a futile gesture, and Eckersley briefly contemplates borrowing the gun to save himself the agony of drowning.

As the water rises to chin level, Eckersley, with the dispassion of a man who has started to surrender to fate, asks Larson whether he has ever thought about death. Larson simply replies, “The Lord has it all planned.” Then he loses his grip and is washed into Eckersley. They are locked in a desperate embrace. Seconds later, there’s a sudden snap as the backpack strap breaks. Together, Eckersley and Larson are hurled into the cataract. Sespe Creek has claimed its last two victims.

THE SPEED AND POWER of the Sespe in full flood overwhelms Eckersley. His mouth fills with water and he gags. The river sucks him down once, then twice. He can’t believe how fast he’s moving. He’s pulled down a third time. His lower back slams into a boulder, causing an explosion of pain so intense that he blacks out.

The next sensation is strange. Eckersley is lying on his back in the shallows, and the water lapping at him feels hot. He figures that can mean only one thing. Death isn’t so bad, he thinks. It’s nice and warm. It doesn’t last, though. In an instant the water is icy cold again, and Eckersley feels the throbbing pain in his lower back. His clothes are torn and he’s shivering on a muddy riverbank. He’s alive.

Stunned, he stands up and sees that he’s still on the north side of the river, perhaps 100 yards downstream from the bulldozer. He starts crawling up the muddy hillside in front of him, crossing the road they just traveled. The slope is bare of brush or shelter. Desperate to escape the frigid wind, he starts digging, clawing at the wet earth with his stiff hands, tearing his fingernails. He makes a hole and wedges himself in like an animal, pulling mud and rocks over himself.

Lightning rips through the sky all around him. Sleet mixes with the rain. There is a piercing and unrelenting pain in his heart. It is so bad Eckersley starts to pray for a lightning strike to end his suffering. The night grinds slowly on. He never sleeps; he just endures. In the morning, he crawls free of his burrow, hypothermic and disoriented. He stiffly descends to the road and starts a shuffling run, away from the crossing. The road is covered with shale and sharp rocks. His feet are bare and start to bleed. But the warmth that comes from physical movement drives him on.

Eckersley remembers they passed some school vans left in one of the campground areas about three miles before the fatal crossing. Once or twice the sun breaks through the cloud and casts its yellow rays on the proud, red peaks above him. It’s a sight of such beauty that Eckersley is compelled to stop for a moment and wonder again whether he might be dead. When he reaches the vans, he’s exhausted, his feet are shredded, and his heart feels as if it’s about to explode. The vans are unlocked. He opens one. It’s full of spare clothing, food, and blankets. There is even a medical kit.

Eckersley still can’t quite believe he will live. He needs to create a record so the world will know what took place on Sespe Creek that night. He roots around until he finds a pen and a Marlboro cigarette carton. He unfolds the carton and starts writing on the inside. It reads like a last will and testament. “Today is Tuesday or Wednesday,” it starts. “My name is John Scott Eckersley. I am the sole survivor, I believe, of an accident that happened last night during a rescue operation in the Sespe Creek area of the Los Padres National Forest.”

Late that afternoon Eckersley hears the thwap-thwap of helicopter blades. He sticks his head out of the van and waves wildly until the helicopter, flying low under the boiling cloud cover, banks toward him and lands. It carries a television news team, there to film the devastation and to look for the overdue boys. The crew carries him aboard while the cameraman films. They take off and fly upstream, toward safety.

Eckersley slumps by a window, staring blankly at the Sespe below. Suddenly the bulldozer appears. There’s a body hanging off of it, exposed by the receding floodwater. A loud cry of pain and sorrow explodes from Eckersley. The crew members look at him sharply. They had assumed Eckersley was just another stranded camper. “Were you in that party?” one asks. “Yes,” Eckersley answers. He starts sobbing, tears streaming down his cheeks.

THE FIRST INKLING in the Cassol home that something might be wrong did not come until Sunday evening, when the boys hadn’t returned. It had been raining for a day and a half, but Jan Cassol didn’t think much of it. She called around, hoping for information. No one knew anything. There was nothing to do but wait.

On Monday night, following Larson’s radio report from Coltrell Flat, word was passed to the families that the boys had been found. It was a huge relief, and Jan went to Ronny and Bobby’s room to lay out their pajamas. But by Tuesday morning there was nothing more. Jan called the boys’ father, Pete (they were separated), and they drove up to Rose Valley together. Lion Camp was in chaos. Men from the sheriff’s department and the Forest Service milled about. Frank Donato’s parents were there, too. But there was no new information. Go home and wait for news, the authorities said. Deflated, Jan and Pete headed back to their car. Before they got in, Jan stood on a bluff over the raging torrent of the Sespe. She had never seen water look so powerful or move that fast.

Back at home, Jan tried to control her fear. They’ll have such stories to tell, she thought. Later than night, she switched on the 11 o’clock news. George Putnam, a local broadcaster, was reporting on the floods. An image of a man on a stretcher filled the screen. It was Eckersley, on his way to the hospital. “One by one we all slipped away,” he said to the camera. Then Putnam read the names. That was how Jan learned that her two sons had died in Sespe Creek. Even after all this time, the memory charges her body with grief and anger.

The next day, the authorities finally called to say they had found a body. It was Bobby. Jan wanted to see him one last time. “I don’t think you should,” the coroner said. “It wouldn’t do you any good, and they lose all the color in their eyes when they drown.” So that was it. Bobby was gone. “Bobby was one of the first to go,” Jan says. “And that means my Ronny had to watch his brother die.”

Ronny was never found. His jacket was picked out of a tree, 14 feet up. In fact, the flood was so fierce and the area so wild, only six of the ten bodies were ever brought home. (The last, Eddie Salisbury, was discovered almost two months later, more than 50 miles downstream.) This is perhaps the cruelest legacy a tragedy in the wild can bestow upon a family; lack of finality is an insidious and unrelenting form of torture. “What if Ronny was alive? What if Ronny was lying there hurt?” Jan says, her voice breaking. “I’ll never feel closure because of that.”

SCOTT ECKERSLEY’S trim little house is tucked into a hillside outside Ojai, high above a valley carpeted with fruit groves. An arbor shades the front door, which swings open to frame a slim, smiling man. Now 67, he has snowy-white hair and ruddy cheeks. There’s a friendly glint in his eye. For the past 15 years he has suffered from fibromyalgia, a wasting disease that has mostly imprisoned him in the simple comfort of the house he built with his own hands. A year after the Sespe tragedy, Eckersley met a beautiful 17-year-old local girl named Jenny. She is standing beside him now. They have one adult daughter.

Eckersley looks exhausted, but he wants to talk. As the lone survivor of the tragedy, he feels he has an obligation to speak. In the years following the accident, he returned to the spot dozens of times. He would sit on a big rock in the middle of Sespe Creek and meditate, trying to figure out why he alone had lived. “How could anybody get out of that stream? How did I get from the middle of the river in that kind of current?” he says. “It’s not possible, it’s not possible.”

Immediately after the tragedyÔÇöweak and still feeling pain in his chestÔÇöEckersley submitted to two lengthy interrogations. EveryoneÔÇöthe Ventura County Sheriff’s Department, the Seabees, the Forest ServiceÔÇöwanted to know what had gone wrong. Why had they left the cabin? Why had they kept crossing rapidly deepening floodwaters? Who had made the decisions? But no one, it seemed to Eckersley, wanted to assume any responsibility.

It was more important to Eckersley that the families hear the real story, and he met with them one night in Canoga Park shortly after the accident. He wanted to tell the mothers and fathers how their children had died and that they had died bravely. “People were falling over fainting and crying,” Eckersley recalls. “Now that I’ve had a daughter and raised her up and know what it would mean to lose her, it just gives me the shivers what those people went through.”

Eckersley also told them of that transcendent moment when one of the boys rose above the fear to express his message of love. Jan Cassol, Bobby and Ronny’s mother, felt her heart crack. Eckersley didn’t know the name of the boy, but she did. Every night, for as long as she could remember, her son Bobby would kiss her as he went to bed and say, “I love you dearly.” Now she knew those words were the last he ever spoke.

“I realized this boy was an enlightened human being,” Eckersley says. Back at Live Oak School, he tried to teach the children to appreciate the gift of life. One night he would talk them into doing yoga in the dark. Another, he would insist they all get up to watch the sunrise. And he retold the story of Bobby Cassol’s words of love countless times. “I was determined to wake up everybody,” he says.

Bobby Cassol’s memory haunts Eckersley to this day. He came to believe that at some point on that doomed bulldozer Bobby ended up in his grasp and that he let him go. It is a sequence that he never mentioned in the weeks after the tragedy. But now, stretched out on his sofa in the late afternoon, he tells me a story he says he was never able to tell anyone until recently.

He stares blankly at the ceiling, and his voice drops to a near whisper. He’s back on the bulldozer, in the middle of the roaring flood. Everyone is fighting to hold on, and he hears a familiar voice yell, “Scott! Grab my hand!” Eckersley is already holding another boy, but he stretches and grabs Bobby’s wrist. The current tears at them. Eckersley feels as if his arm is about to be ripped off. His grip loosens, just for an instant, and that is the only weakness the river needs. Bobby is swept away. The other boy is soon carried away as well. “If I’d only been stronger,” Eckersley says. “If I only could have just pulled him up in front of me.”

Early in 2006, he received a phone call. Debra Cassol wanted to talk. She and Eckersley started to correspond. For the first time, he talked about his guilt. Debra also started to open up. She told Eckersley about the guilt she felt, too, over not speaking up about her premonition that the boys wouldn’t be coming back. It was comforting to talk with someone who really understood.

EVEN NOW, FAMILY MEMBERS of the boys who died in the Sespe tragedy can’t let go of the most difficult question: Why were the boys taken out into the storm? “If only they had left them alone in the cabin,” Jan Cassol says. “They killed my kids. I believe it to this very day: They killed my kids.” She slams her fist on the table. “It eats at you,” she says, her eyes flashing. Debra knows a terrible, monstrous mistake was made. But she wants to let the anguish go, to forgive, and she can’t quite bring herself to heap all her anger on Larson, Sears, and Greenhill, the would-be rescuers, for what happened. “They died as well,” she points out.

The days following the tragedy were a blur of confusion for Pat Larson. She moved with sons Steve and Mark to her parents’ house, back in Taft, the dead-end town Chet had escaped. “I was scared to death,” Pat says. She had to tell her two young sons that their father wasn’t coming home. A few days after the accident, Chet’s parents told her his body had been recovered. They wanted her to help identify him. She refused. “I can’t go. I’m not supposed to. It’s not him,” she told her angry and grieving in-laws. They took Chet’s younger brother, Max, instead. Max walked into the morgue and saw the left hand of the corpse sticking out from under a sheet. There was no sign of a wedding ring. Pat had been right: It wasn’t Chet. It turned out to be Robert Samples. The body had been so battered beyond recognition it was hard to identify. “Of course, they never found his body, but I knew they weren’t going to,” Pat says.

Pat was relieved that Chet had disappeared, as if he had been transported straight to heaven. And she drew at least some peace from the knowledge that he had died doing something that made him happy, and not in the oil fields. “He loved being a sheriff,” she says. “He was a Christian, and he was ready to go.”

In a way, the Larsons were lucky. Chet was a husband and father, but his family didn’t see him as a victim, and he was a man who had made his own choices. For the Donatos, Rauhs, Cassols, and Salisburys (who also lost two boys, Danny, 13, and Eddie, 11), there would always be anguish and unanswered questions.

Before I left California, I managed to track down Pat Salisbury. He had been 17 and one of seven children when his younger brothers died. Today he is a burly 56-year-old contractor who still lives in the area with his wife and three children. His parents are both dead, buried next to Danny and Eddie. But Pat, who still has a very hard time talking about the accident, explains how it blew his tight-knit family apart. “We all just kind of went, This can happen at any minute,” Salisbury says. “It was devastating, absolutely devastating.”

Pat struggled for years with rage and alcoholism. It was only after a counselor in 2003 stumbled on the fact that his two younger brothers had been tragically killed decades earlier that he was given the belated grief counseling he needed. “People are afraid of death, but death is a part of life,” he says now. “Enjoy every day you are alive, because you never know when you will end up on a bulldozer. You just don’t know.”

Steve Larson found a kind of balance, too. Growing up, he never liked cops, and he wondered all his life whether he would have liked his father and whether his father had been a hero or responsible for the deaths of six young boys. Retracing Chester Larson’s tragic march to the final crossing has helped him see his father through the shroud of death. He knows now that Chet was a decent man who made a terrible yet honest mistake. He knows now that his father, and Greenhill and Sears, were preoccupied with completing their mission and that what none of them realized was that they were in the midst of the heaviest rains ever to fall in the area. In four days, more than 16 inches of rain poured down the hillsides into the Sespe Creek bed. Dulled by cold and exhaustion, they simply failed to comprehend the brutal, unholy potential of the flash flood that would result.

Later Steve writes me: “Life is a series of calculated risks. I no longer accept that his death was ÔÇśmeant to be.’ Maybe I will have a better understanding of the greater purpose of his death someday. For now, I have a wife and two children who need me (as he did), and I am going to put them first and make sure I make it home at the end of the day.”