THE SONS OF HASSELHOFF, GEOFF AND MARK, slipped their newly minted driver’s licenses into their wallets, donned custom-printed t-shirts displaying the album covers of the beloved Knight Rider/pop singer, hopped into their tiny 1986 Volkswagen Golf 1.6 CL, and headed south out of Reading, a commuter suburb west of London.

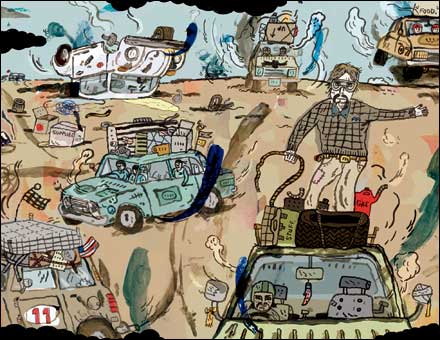

Banger Rally Map

Map by Mark Todd

Map by Mark ToddDown in the English Channel port of Poole, meanwhile, the Conedodgers, a team consisting of brewpub designer Declan Hicks and marine mechanic Ed Parke, were playing Tetris with 12 cases of Carlsberg beer, concealing the suds beneath a plywood pantry they’d crammed into their 1992 Volvo Estate wagon. In London, Benja Hedley and Denis Meehan, the Badger Racing boys, hitched the shabby camper they’d purchased on eBay behind their 1984 4×4 Mitsubishi Montero Magnum, then gave each other ceremonial Mohawks before motoring out of town. And on the other side of the city, firefighters were shutting down a BP station where the gas tank of a little red 1991 VW Polo—driven by Team SloMoShun’s Emma Barber and packed to the gills with camping gear, empty fuel cans, and plastic toys—was spurting unleaded all over the concrete.

Like hydrocarbon-fueled lemmings, they, along with 33 other teams from all reaches of the United Kingdom, were rushing headlong toward ferry crossings to France. Once on the other side, they were counting on their exquisitely crappy cars, many pulled from junk heaps or taken off blocks, to carry them to the southern tip of Spain, over the Atlas Mountains in Morocco, and across the roadless sands of the Sahara. It was the first day of the Plymouth–Dakar Challenge, and, with 4,500 miles and at least three weeks of travel ahead, the shit parade was under way.

MY TEAM, FOR ONE FLEETING MOMENT, was leading the pack. At a dealership outside Toulouse, France, Sid Horman, 43, his 13-year-old son, Martin, and I watched our 1991 SEAT Malaga 1.6, a bland, Spanish-made diesel sedan we’d named Ros Bif 1—a nod to a favorite French epithet for Brits, “roast beef”—as it puked an oily, brownish-green gravy from its coolant reservoir while an impassioned mechanic threatened to impound the car for safety violations.

We’d hit the road two days ahead of the Challenge’s official February 18 start date and had already pushed Ros Bif to her limit, revving up to 91 miles per hour on the slick motorways of Gaul until her head gasket blew. After a few poorly translated lies, we managed to ditch the French mechanic, praying the engine wouldn’t go Chernobyl before we could stop for repairs in Spain.

And, really, there was no hurry. Teams enter the PDC with one goal: making it to the finish. The event is a mad Englishman’s answer to the Paris–Dakar Rally (now Lisbon–Dakar), the notorious 6,500-mile pro-am event in the North African desert that involves, among other expenses, a $10,000 entry fee and $250,000 off-road racing cars serviced by professional chase crews. While the Paris–Dakar offers prize money in the hundreds of thousands, the PDC—or Banger Rally, as it’s widely known in the UK—ends with a charity auction.

I’d signed on as Sid’s co-driver—a loose term, considering I’d neglected to learn to drive a stick—after he’d responded to a message posted on the PDC’s online chat room. During our one brief conversation before I flew to England, Sid, who admitted to having killed a couple of bottles of wine before dialing, described himself as a semiretired international banker from the Isle of Jersey now living on a farm in Devon.

Translation: He was a former bank compliance officer who’d had a breakdown and moved to the countryside to soothe his nerves. Now, two years later, he was taking medication for manic depression while making ends meet by selling Kleen EZ products door to door and stabling neighbors’ horses. Six feet tall with broad shoulders and a Nixonesque perpetual five-o’clock shadow, he is a chronically nervous man. When things go wrong, as they often do for him, Sid likes to drive. And not at the back of the pack.

“They call this a challenge, but really it’s still a race,” he confided to me as he gunned Ros Bif into Spain. “You still want to be first!”

THE PDC BEGAN IN 2003, when Julian Nowill, then a 43-year-old millionaire stockbroker from Exeter who refurbished East European junkers on the side, decided he wanted to test the mettle of the Soviet Ladas—the Cold War “car of the people”—that he’d been collecting since the eighties. In a local newspaper, he invited others to join him on a route that independent explorers had traveled in 4x4s for decades. The finish line was set in Banjul, the capital of Gambia, but Nowill dubbed the event the Plymouth–Dakar Challenge to play up the mockery of the “serious” Paris–Dakar race.

The ploy worked: The story got picked up by the BBC and generated an avalanche of interest. That year, 43 teams in ancient Peugeots, Mercedeses, and Renaults followed Nowill south from Plymouth, despite the fact that they had no clue how they would be greeted at African borders or if it was possible for two-wheel-drive vehicles to manage the Sahara.

To the surprise of many, they made it to Banjul—minus only a couple of teams. The saga generated enough buzz for Nowill to organize a repeat in 2004, though he didn’t make the drive. By the time I joined Sid and Martin in 2005, the PDC had become a full-blown cult phenomenon, with some 800 applications for the rally’s 200 slots, which are divided into four waves of roughly 50 cars each that depart between December and February and finish some three weeks after they leave the UK.

The event is unique in the world of auto rallies, drawing men and women of all ages, moneyed car buffs, married couples, fathers and sons, complete strangers, and, naturally, the mechanically inclined. “It’s not as radical as it was in the beginning; there are more middle-aged charity-focused people,” says Nowill. “But I try to keep the spirit alive. Complete lunatics go to the top of the applicant pile.” So far, no one has died, but there have been plenty of near misses, and with every running, one or two cars are usually abandoned in the Sahara, where they’re stripped for parts by Bedouin. Meanwhile, quite a few noteworthy vehicles have made it through the sticky sands. In 2004, Creamy Treats, a fully functional ice cream truck stocked with popsicles, made it to Banjul before being converted into an ambulance for one of Gambia’s remote upriver cities.

Nowill skipped the drive again in 2005, but his spirit was ever present in the form of hushed admonishments—”When Julian first did the race, he did it this way”—and a 15-page road book that offers teams his vague outline of the route in short, koan-like entries that usually just confuse people. The teams, selected by Nowill, pay a ┬Ż00 ($355) registration fee. In return, they receive an official PDC number, the road book, Lonely Planet guides to Morocco and Senegal, and an invitation to the launch party in Exeter. Entrants also agree to the PDC’s three commandments: Cars can cost no more than ┬Ż00; preparations and repairs can cost no more than ┬Ż5; and rules are made to be broken.

Sid was uncommonly fond of commandment three. He dumped nearly $1,500 into the Malaga in the year leading up to the rally, paying for upgrades like new tires and high-powered spotlights. He’d also decorated the exterior with dozens of colorful stickers guaranteed to impress bystanders on our route, ├Ā la: LIFE’S A BITCH, THEN ONE PULLS OUT IN FRONTOF YOU and I BRAKE FOR BABES.

At our bon voyage with the Horman family, Sid narrated into a video camera as he raised a bottle of champagne over Ros Bif‘s roof. “I don’t know if we’ll make it to Gambia—or even make it out the drive,” he said. “But here’s to a great adventure!” With that, he swung the magnum down, but it failed to crack, and the car began to roll slowly back down the driveway, like a puppy slinking away from its master.

FROM DEVON TO FRANCE and into Spain, Sid, always clad in a red Ferrari-branded polo, unleashed torrents of babble. He calculated mileage, rehearsed schedules, and celebrated our luck in scoring 15 boxes of Gulf War–era C rations to get us through the Sahara. He shared stories of near-death mountain-bike crashes, of his days managing a competitive motorcycle team, and of his stint teaching “advanced driving techniques” to British cops back in Jersey.

But by the time we reached the first major PDC rendezvous point, the parking lot of the Hotel Camillas, in the small southern-Spain resort town of Sotogrande, Sid’s soliloquies had turned from engine blocks and adrenaline sports to murder and revenge. At a roadside rest area outside the city of Benidorm, thieves had smashed Ros Bif‘s rear passenger-side window and grabbed what they could reach.

“I can’t believe it! Druggies!” he kept repeating.

“Dad, it could have been lowlifes!” Martin chimed in.

Whatever they were, they’d nabbed the laptop computer case with Sid’s and Martin’s visas and passports, our car documents (most forged), a bag containing Martin’s asthma inhaler, and some of Sid’s medication. “If I’d found them,” Sid steamed, “they’d be dead for sure.”

As we talked through our options, the lot filled with all manner of automotive monstrosities. Some were lovingly painted with cartoon camels. Others looked like they’d been colonized by armadillos. Emma Barber’s Polo was still leaking gas, the Badger Racing boys had had to scour a scrap yard in Gibraltar to get a new gearbox for their Montero, and the Conedodgers had lost an exhaust pipe.

“We took a corner pretty wide and almost got pulverized by a logging truck in the middle of France,” Declan recounted at the Camillas bar. “That was a bit of a brown-trouser moment.”

Over the next two days, jacks and wrenches were passed around like doobies as drivers tweaked their brakes, zip-tied exhaust systems, and bolted on sump guards to protect gas tanks from rocks. The most fortunate teams stayed for a night or less before setting off in groups of five or six to the ferry terminal at Algeciras, for the crossing into Morocco. The unlucky, including us, were stuck “sorting” things for a couple of days. We sent Ros Bif off to have her head gasket repaired while Sid and Martin boarded an overnight bus to Madrid to plea for new passports. I waited at the hotel for a DHL shipment with Ros Bif‘s new (and legitimate) paperwork.

At last, the Malaga returned from the shop. Sid and Martin returned also, haggard but with shiny new credentials and rejuvenated will. By the time we were ready to roll, our head start had evaporated completely.

AT NIGHT, THE MOROCCAN HIGHWAY looks like any other truck-filled thoroughfare, but pull off into a village and you’ll find the streets buzzing—groups of young men strolling, talking, and conducting business to avoid the heat of the day. An hour after entering the country, we pulled into a floodlit village to top off the tank, but the shadowy figures and maze of streets caused Sid to beat a fidgety retreat. An hour later, he dared a brief pit stop at a bright neon Afrique gas station, grabbing high-octane coffee and bread. Then it was south, south, south, zipping between the lumbering trucks into the darkness. At six in the morning—as the muezzins called morning prayers and the sun revealed the dusty skyline of Casablanca—Sid pulled into the financial district, parked Ros Bif in the shade of the most Western-looking bank he could find, and fell asleep in the driver’s seat.

We lagged for three days as Sid and Martin negotiated replacement visas with the Mauritanian embassy. Then we jammed south to Marrakesh in a fever, convinced that we’d fallen dangerously behind the pack. Just as we were giving up hope of seeing any other rally cars, we spotted Rural Chic—a team of two recent grads from Bristol University in a canary-yellow 1978 Fiat 128—loitering at the edge of a gas station.

Over the next hour, eight more teams joined us to build a safe-passage convoy over the Atlas Mountains. The three cars of Team SloMoShun appeared, as did the Sons of Hasselhoff and the Conedodgers. Our conga line chugged nose to tail up the narrow, shoulderless highway that winds steeply out of Casablanca through 11,000-foot peaks before dropping to the flat plains of the Sahara. Around every turn we glimpsed vistas of surrounding desert before plunging back into lush mountain valleys.

But Sid wasn’t interested in scenery. We were the caboose, and he wanted pole position. As the convoy began ascending a long incline, a glint came into his eye. “Watch this,” he said, pulling into the opposite lane and gunning the motor. Ros Bif did her best. She passed one car. Two cars. After what felt like ten minutes, we were halfway to the front, but then a freight truck crested the hill ahead of us and began barreling down on our little Spanish sardine can.

Sid had two choices: crank the wheel to the right and knock Team SloMoShun’s blue Citr├Čen XL into the abyss, or plow headfirst into the rig. For a heartbeat he did nothing, then, at the last second, the semi swerved into the roadside rocks, the Citr├Čen edged right, and we squeezed through the gap.

The glares from the other teams pierced Ros Bif like lasers, but Sid kept his eyes forward, flooring over the top of the crest until he had taken the lead. “I’m trained in advanced driving!” he fumed. “If they all knew how to drive, there shouldn’t have been a problem!”

THE PARCHED HEART OF THE PDC is the three-day, 350-mile off-road desert crossing through the Parc National du Banc d’Arduin, in the south of Mauritania. There are no gas stations, freshwater sources, or route markers, so it’s necessary to hire a guide and carry your supplies. Cars spin into sandpits, and radiators and gas tanks are bashed to pieces. Midday temperatures average 90 degrees.

With such potential for peril, I ditched Sid and Martin in Dakhla, the southernmost town in Western Sahara, after Ros Bif blew yet another head gasket. If she punked out again in the sands, it would be almost impossible for the other teams to absorb three extra bodies and our gear. “So you’re abandoning us,” Sid said icily. “I see. When the going gets tough, you quit.” He was looking for an excuse to launch a tirade, but I refused to light his fuse.

I set off the next afternoon in Team SloMoShun’s VW Polo with Emma Barber, a tall blond businesswoman in her mid-thirties. Also on her team were her father, John, a stout 70-year-old mechanic with his wrist in a cast, and his wife, Fuzzy, a spunky 60-year-old with erect silver hair, both crammed into the Citr├Čen. Emma’s half brother, Joe, and his friend David, both in their thirties, rounded out the caravan in their eight-cylinder Rover 800. SloMoShun had earned a bevy of nicknames, including Team Panic, for their hysteria-inducing screwups, including leaving Fuzzy behind at a Spanish toilet stop for the better part of an hour. I’d dubbed them Team Posh for their habit of staying in luxury hotels and because they’d brought along a dozen or so bottles of red wine.

Our guide, Hamid, led us into what felt like a random stretch of Sahara in his white Toyota pickup, cajoling us with constant hand signals to step on the gas to avoid sinking. We blazed across the flats at 50 miles per hour until, 20 minutes in, Emma’s Polo snagged in a drift. Everyone unloaded to dig us out, jamming carpet scraps under the tires for traction. “Oh, make sure to take some pictures!” Emma squealed.

At least a dozen rescues later, we stopped to camp. It took Team Posh an hour to put up one of four spanking-new four-man tents; in the meantime, I erected the other three and cooked dinner. “Oh, you’re just what I thought an American would be like!” said Fuzzy. “So self-reliant!”

But the bonhomie didn’t last long. The next morning, Emma’s Polo stalled in an especially soft stretch of sand and we decided to leave the car behind. “Goodbye, little Polo,” a grief-stricken Emma told her companion as we squeezed into the cab of Hamid’s truck. Throughout the afternoon, we stopped time and again to morosely dig the other cars out. At one point, there was a wave of panic when John’s hip went out of socket as he tried to peer under the Citr├Čen. “Get in your truck and pull these cars out!” Fuzzy demanded of Hamid. “We’re not paying you so this old man has to dig!”

We slogged onward and, the next afternoon, reached Nouamghar, a small fishing village where the dunes spill onto a treacherously narrow beach, the only route back to the highway, some 50 miles to the south. We woke at dawn to time our sprint with the three-hour low-tide window, barreling along at 60 until the Citr├Čen dug in. We spent half an hour freeing it. With ten miles to go, the Rover got stuck; waves lapped at our feet as we furiously dug it out.

“Allez, allez, allez!” Hamid shouted. Five miles to go and bigger sets were slapping our tires. Then a mass of people materialized from the dust, diving out of our way. We’d made the highway. Fuzzy, who’d been driving, exited the Citr├Čen and lit a cigarette. “Oh, God, that was dreadful,” she said.

We hammered on to Mauritania’s capital, Nouakchott, where Team Posh found a restaurant serving Heineken and, praise heaven, a passable plate of salty English chips.

ON THE OUTSKIRTS OF SAINT-LOUIS, Senegal, Team Posh crashed in an expensive beachside resort; I hitched a ride with a local man to Zebrabar, a campground 20 miles south of the former colonial port where other teams were taking a post-desert layover. After a couple of days deflating, I squeezed into the backseat of Team ReVolvor’s gray wagon, piloted by John and Sam Drew, a father-and-son duo from Malmesbury, in southwest England.

The tail end of the winter harmattan winds blew like a blast furnace for three days. As we limped the final 400 miles through Senegal to Banjul, the faded golds of the Sahara dissipated into brick-red, the macadam deteriorating the farther south we drove. Wherever we stopped—Touba, Mback├®, Kaolack—children assailed our ten-car convoy, screeching “Bon-bons!” and “Cadeaux!” while climbing onto bumpers and roofs, reaching through open windows like zombies seeking brains.

And then, with no fanfare except for a billboard advertising Saddam Gunpowder Green Tea, we were on the quiet late- afternoon streets of Banjul. The PDC vanguard had finished several days earlier and been escorted by police to the national soccer stadium, where they paraded around before local politicians. We caught up with them in the lush patio bar of the Safari Garden Hotel to recount our epics late into the night over beans on toast and prodigious quantities of JulBrew, the local lager. The 34 cars that survived our wave were mostly sold to local taxi drivers and fetched a million Gambian dalasis, or roughly $40,000, which was distributed to Banjul’s woefully undersupplied Victoria Hospital and other groups.

Sid and Martin made it to the finish line, though not as grandly as planned. A few hours after their departure from Dakhla, Ros Bif blew another gasket, dying in the poorly marked mine field separating Western Sahara and Mauritania. She was towed to the outlaw town of Nouadhibou and sold for $300. Sid and Martin were forced to cadge a ride in a guide’s truck for the remainder of the trip. Adding further insult, the C rations turned out to be spoiled, causing Martin to spend a night heaving a day’s worth of junk food.

Sid’s wife, Ann, and older son, Peter, flew down for a family vacation at the Gambian coastal resorts, greeting us at the Safari Garden with two bottles of champagne. Sid grabbed one and uncorked it. All but a fraction of the bubbly spewed out. “Oh, well!” he said, uncorking the second. It did the same thing, leaving him standing there holding a bottle that was half empty.