WITH A TWIST OF HIS SEGWAY’S handgrip, Mike Akatiff goes off looking for a fight. Deftly navigating the nerdy scooter, he glides past dozens of tented, makeshift motorcycle race pits set up in the middle of Utah’s Bonneville Salt Flats. The oil-stained outpost, situated on top of an ancient lakebed in western Utah, is littered with bikes in various states of assembly: a custom-framed Harley here, an ancient Enfield there, and crazy-modded Suzukis and Kawasakis all over the place. Akatiff barely gives a glance. Almost nothing in this internal-combustion ghetto can sniff at the monster machine he’s brought.

Motorcycle Utah

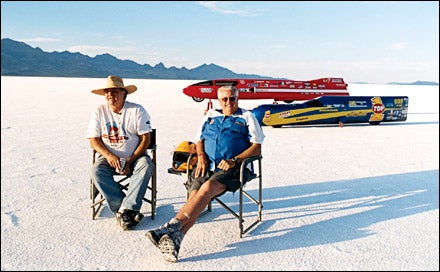

A speed track at Bonneville, Utah, September 2006

A speed track at Bonneville, Utah, September 2006Motorcycle Utah

Members of the Salt Flats tribe goof around on a Honda scooter

Members of the Salt Flats tribe goof around on a Honda scooterMotorcycle Utah

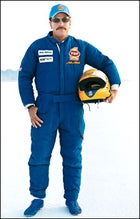

Ack Attack rider Rocky Robinson

Ack Attack rider Rocky RobinsonMotorcycle Utah

For people who love mechanized speed, Bonneville is like Everest—the ultimate dream and a big part of “who we are.”

For people who love mechanized speed, Bonneville is like Everest—the ultimate dream and a big part of “who we are.”Akatiff, 61, rolls up to a crowd of greasers, hog riders, 5-Ballers, dirtbags, biker babes, and one of the guys he’s looking for: Denis Manning. Like Akatiff, the 60-year-old Manning is here to set the salt on fire. Both of them have built, from the ground up, supercustomized vehicles called motorcycle streamliners: rocket-shaped, fully enclosed bikes that pack gobs of horsepower and can travel faster than 300 miles per hour. Each man has come to this September 2006 event—formally known as the International Motorcycle Speed Trials by BUB—to pursue the most elusive prize in the obscure sport of land-speed racing: the official record and bragging rights that go to the creator of the world’s fastest motorcycle.

Manning steps into the bed of a pickup and calls a couple hundred people to attention. As the meet’s chief moneyman and founder, he dutifully reviews a few rules for the riders, most of whom have brought less exotic hardware and would love to touch 150 miles per hour. “If you can’t stop, veer away from the interstate,” Manning says. “Avoid hitting the portable toilets bordering the track.” Then the potbellied Manning, a 40-year veteran of the salt whose nickname is BUB (for “big ugly bastard”), gets down to more personal needs.

“Cooperate with the streamliners,” he says while zeroing in on Akatiff, a tall, wide-shouldered guy who’s standing even taller on his Segway. “We want to make sure history is done here.”

That won’t be easy. In a sport that’s often guilty of more show than go, the streamliners have had a bad run in recent times. Every year, two or three of the sleek machines arrive at the salt full of promise. And every year they tank. The rigs’ owners, drivers, and crews usually have good excuses (wet salt, bad crosswinds), but for whatever reason, the current motorcycle speed record of 322 miles per hour—set here on a streamliner by rider Dave Campos—hasn’t been beaten for 16 years.

Which, to Akatiff, does not compute. A goal-oriented entrepreneur and gearhead who only recently decided to get involved in land-speed racing, he’s the methodical type. This morning, he had his uniformed six-man crew up and ready at dawn, and he’ll tell you again and again that what a job like this needs most is organization and focus.

“To me, it’s pretty simple,” Akatiff explained in his San Jose warehouse/garage two months before heading off to Bonneville. “Design everything around what it will take to do the job.”

Just minutes after the 11-mile-long, arrow-straight track opens, Akatiff and his crew roll their 20-foot, $125,000 streamliner, the Ack Attack, to the starting line. Akatiff checks his pre-race to-do list and turns to his rider—a compact, mustached guy named Rocky Robinson. “Suit up,” he says.

Robinson is a 45-year-old streamliner veteran who badly wants to nab the record, in part because he’s got a personal feud going with Manning. He zips up his racing suit and shimmies into the streamliner. After squeezing supine into a cockpit that’s as claustrophobic as a coffin, his butt just six inches off the ground, he hopes to top out at nearly half the speed of sound. Once Robinson is in place, Akatiff gives the nod. The deep-blue land missile starts up with a smooth and guttural blat.

LAND-SPEED RACING means exactly what it sounds like—going as fast as you can on land, whether you’re riding four wheels or two. Since the 1940s, speed freaks have flocked to Bonneville because the 38-square-mile salt flats are one of the world’s biggest wide-open drag strips. They’re hugely unexciting on a mountain bike, but they’re perfect for answering the age-old question “How fast will it go?”

For all the power and velocity on display at Bonneville, the number of fatalities is smaller than you’d expect—eight in the 58-year-old modern era of salt-flats racing—but there have been plenty of heroic wipeouts, miscues, and glitches. Back in 1914, automobile driver “Terrible Teddy” Tetzlaff reached 142.8 miles per hour on the salt, grabbing the first land-speed record ever set there. Unfortunately, the necessary officials weren’t around, so the drive didn’t go into the books. Twenty-one years later, car-racing legend Malcolm Campbell came to the salt after word had spread that Bonneville was hard-surfaced, table-flat, and, despite the interstate running across a portion of it, relatively desolate, meaning there was room to run and make mistakes. But a timing-equipment malfunction almost nullified Campbell’s white-knuckled, world-record drive of 300 miles per hour. Terrified and jangled, he never raced again.

The two-wheeled competition had its own ragged beginnings. Back in 1948, a Kansas rider named Rollie Free decided he could improve his speed by taking off his clothes; his record run of 150 miles per hour was achieved with him bellied flat onto the seat, wearing only a shower cap, a bathing suit, and sneakers. Then there was Burt Munro, the nutty New Zealander who inspired the 2005 movie The World’s Fastest Indian. Munro’s claim to fame was his sketchy, much-modified Indian motorcycle. In 1962, he coaxed the 42-year-old bike to 162, a new record.

A few years later, the wayward sport drew in Denis Manning, a 24-year-old motorcycle racer and self-taught designer who spent two years building a wildly aerodynamic streamliner in the tiny garage of a Southern California duplex. Problem was, the bike wasn’t fast enough. Ultimately, Harley-Davidson jumped into the project, and after a few near-catastrophic test runs, driver Cal Rayborn and Manning’s Harley Streamliner set a world record of 265 in 1970.

Manning hasn’t enjoyed the same glory since. Sponsorship dollars, never much to begin with, became increasingly difficult to secure as big-name manufacturers realized that the exhilarating time-trial competitions were a little boring for folks sitting outside the cockpits. Manning’s mark was broken in 1974 and 1975 by Don Vesco, a celebrated road racer who upped the ante yet again in 1978. That record stood until 1990, when Campos and his Easyriders streamliner, funded in part by 10,000 fans who donated $25 each, showed up at Bonneville.

Manning, who owns and runs a successful aftermarket exhaust-pipe business in the small Northern California town of Grass Valley, wants the record back. He says he doesn’t care if anyone lines up to help him defray the costs of Seven—his seventh and newest streamliner, which he claims has cost him $8 million. “This isn’t a gentleman-start-your-checkbooks kind of thing,” he says. “It’s a Don Quixote thing.”

A valiant proclamation, for sure, but one that makes Akatiff and other land-speed racers roll their eyes. “Eight million? I have a lot of respect for Denis, but he tends to exaggerate,” says Akatiff. “Personally, I think he’s spent about $7.9 million too much and been in the sport about 37 years too long.”

To improve his chances, Manning created his own race at Bonneville, which is independent of the more famous, automobile-dominated Speed Week, held in August. Now in its third year, Manning’s event is an exclusive meet where motorcycles don’t have to compete with cars for the track and riders can take their best shot. This year’s race program declared the vision boldly: WE WANT DREAMS BORN, WE WANT RECORDS BROKEN.

BUT THIS IS LAND-SPEED RACING, and at the 2006 event, the first thing to break is the track’s communications system. Two hours after arriving at the start line, the Ack Attack crew wait to get green-lighted as they wilt in the midday sun. Akatiff paces around the streamliner while multitasking. In one hand he holds a compact anemometer to check for crosswinds; the other hand flips open a cell phone.

“All those high-end walkie-talkies, and BUB has no communications at mile 11?” he asks, shaking his head. “Don’t they know Verizon works really good out here?”

If Akatiff seems impatient, it’s because he’s obsessed with results. As a kid growing up in San Jose, he once worked 13 hours straight to build an oscilloscope, even though he didn’t care what an oscilloscope did.

“Mike kind of had a computer brain,” recalls his older brother George. The Boy Univac followed George into off-road motorcycling and won a few amateur competitions, but he preferred the fix-it role. In 1969, Akatiff went to work as lead wrench for Jim Rice, a top dirt-track-racing pro. In the seventies, he went on to launch successful companies that designed and manufactured motorcycle parts and tools.

In 1982, while he was going through a messy divorce and custody battle, Akatiff got a pilot’s license, bought partial ownership of a plane, and flew all over the place. While doing all that buzzing around, he got annoyed by a serious shortcoming in airplane instrumentation. There was no reliable, affordable device that could beam a private plane’s elevation status back to air-traffic-control towers. In 1986, he invented an altimeter gizmo that quickly became essential equipment for small-plane pilots. Within weeks, Akatiff had $335,000 worth of orders.

In October 2002, virtually retired at 57, Akatiff went to a semiannual gathering of old off-road riders. Around a campfire, he asked about an absent member of the gang, a mechanical engineer from Southern California named Sam Wheeler. When the reply came that Wheeler was at Bonneville, trying—as he had for years—to capture a world record with his motorcycle streamliner, Akatiff announced that he could snag that prize in no time flat. Everyone laughed—except Akatiff.

“Don’t tell Mike he can’t do something,” says his wife, Christy. “Red flag.”

By early 2003, Akatiff had committed half his San Jose workspace to building a streamliner that would become the Ack Attack. Inside the 4,000-square-foot area, there’s a dynamometer for engine testing, computer-controlled metal-cutting machines, and drill bits as thick as corncobs. Akatiff drafted his inner circle of retired riding buddies—who also happen to be welders and machinists—to volunteer. A couple of them consistently put in 60-hour weeks, working alongside Akatiff while he mastered engine-control software and consulted with an aerodynamics expert.

By deploying such talent and spreading the cash, Akatiff accomplished in 18 months what other streamliner builders don’t achieve for years. In its debut year of 2004, the Ack Attack reached a blazing 328 miles per hour at an event not officially sanctioned for world-record attempts. The message was sent: In the history of the sport, no rookie team had ever put on such a performance.

“It’s hard not to be impressed by Akatiff’s operation,” says Tom Evans, the chief motorcycle inspector for the Southern California Timing Association, which oversees many of the land-speed events at Bonneville. “That guy is the real deal.”

AT ABOUT 2:30 p.m., Radio BUB crackles to life. Rocky Robinson and the Ack Attack inch over the start line, followed immediately by Akatiff in his black Dodge pickup. The truck’s bumper is rigged to give the tippy streamliner a 40–mile–per–hour running push. Within a quarter–mile, Robinson hits the gas, turning the docile streamliner into a pissed–off cheetah. There’s a deafening growl as the Ack Attack roars away.

şÚÁĎłÔąĎÍř the realm of land–speed racing, Robinson is a mild–mannered guy who gels his black hair to spice up his insurance–salesman looks. He manages a tile store in Grass Valley, but he used to have a more exalted job as a corporate vice president for Manning, who unceremoniously ousted him in the fall of 2005 during a temporary economic slump. Getting the boot also meant saying goodbye to Manning’s streamliners. The dismissal still makes him mad.

“I helped turn that company into a multi–million–dollar business,” Robinson will tell me later, away from the salt. “Where I work now is about eating and keeping the lights on.”

As Robinson accelerates down the track, he puts himself on a tactical tightrope: Too hard on the throttle and he could spin the rear wheels and lose valuable momentum. Not aggressive enough and he won’t wring out all of the Ack Attack’s potential. Robinson runs through the bike’s six–speed transmission by redlining every gear, shifting only when a gear–change light comes on inside the cockpit. In Bonneville’s unchanging, canvas–white landscape, the beacon is one of Robinson’s best visual indicators that he is, indeed, hauling ass.

At mile five, Robinson anxiously feels a crosswind that causes the Ack Attack to list to the left. He doesn’t fight it, instead letting the bike drift even farther left, toward the edge of the 120–foot–wide track, the course markers, and the portable johns. He has to. Unlike regular motorcycles, streamliners don’t turn when leaned, so Robinson can’t change directions until he gets the motorcycle’s mass reoriented directly over its wheels. Once he “catches” the bike, he carefully steers his way back to middle.

The power of the machine is incredible. Akatiff’s recipe for a successful streamliner includes two highly potent Suzuki Hayabusa motorcycle engines. In the Ack Attack, they generate a racecar–like 900 horses, thanks to the addition of modified pistons and connecting rods, high–octane racing gasoline, and an oversize, whining turbocharger capable of force–feeding huge gulps of air into the engines’ combustion chambers. All that power goes to the rear wheel via custom–made transmission shafts and industrial–strength racing chains, which get so hot that Akatiff uses nozzles to constantly spray them with ice water.

When Robinson enters and exits the mid–course, mile–long timing trap, he sets off lights located at each end, which capture his average speed. By this time he’s covering two football fields per second. The tires are designed with paper–thin tread to avoid excessive heat buildup; otherwise they might boil and melt off the rims.

At the far end of the course, Robinson hears the good news: He reached the unprecedented speed of 344.673 miles per hour. But nobody is high–fiving just yet. The rules state that he has to make a second, return run within two hours. (The second run negates any advantage gained from tailwinds; the two hours give crews time to make repairs.) His official speed will be the average of the two runs.

Minutes later, Robinson takes his second run, going back through the trap with a whoosh. From the pits, which double as the meet’s front–row seats because they’re located dead–center on the track (but safely off to the side), the Ack Attack’s run sounds hyperbolically fast, with a jetlike shriek that arrives just after you watch the thing streak left to right across the horizon. Even before the bike comes to a halt, the results are announced over the radio: “Streamliner through the mile, 340.922. Average speed: 342.797.”

Just like that, in his first set of runs, Robinson has smashed the 16–year–old record. He climbs out, pumps a fist, and finds Akatiff to deliver a hug. No sooner is the bubbly spilling than the boss pulls Robinson aside.

“So far, so good, Rocky,” he says. “We’re right on plan. Now we’re going to see what we can do to go faster.”

WHILE AKATIFF PLOTS to raise the bar, it’s life as usual in the pits. A woman sits astride a painstakingly modified Harley, complete with a custom–painted gas tank featuring a naked nymph straddling a salt shaker. She’s waiting with dozens of other riders for a few fleeting minutes of track time. Elsewhere, there’s a guy whose “pit,” like so many others, includes little more than a dinky canopy, a workstand, and milk crates that double as chairs. He soldiers on, with a wrench in each hand, at the rear end of a 50–year–old Vincent motorcycle.

Such are the realities at Bonneville: It’s a place for people who thrive on mechanized speed, and it’s obvious why they love it here. “The reason we go down the track is the same reason Hillary went up the mountain,” says “Landspeed” Louise Ann Noeth, a former land–speed team member and author of the book Bonneville: The Fastest Place on Earth. “That’s part of who we are.”

The streamliner guys feel the same tug, but their machines are from another planet. Streamliners don’t even start as street machines. Instead, they employ hundreds of custom–made parts that get field–tested at most a few times a year. Streamliner builders don’t work on the premise of whether something will go wrong but when.

Manning’s career has been haunted by technical failures. Two years ago, with Robinson ripping along at 290 in Seven, the fire–extinguisher system short–circuited. As chemical agents rained down on him, Robinson tried opening the dragster–style parachutes, but they failed. In a last–ditch effort to save himself, he slammed on and quickly overheated the ancillary brakes, which stopped the bike but also caught fire. Less than ten seconds after Robinson got out of the burning motorcycle, heat buildup in the rear tire made it explode.

BUB 2006 threatened to trigger similar fireworks, because it promised to be exceptionally fast. Previous months had seen almost no rain at Bonneville, meaning the salt would be drier and the course could extend twice as long as it does after a typically wet summer. A longer track means more time to build up speed. It also means more opportunity for those custom–made parts to fail.Â

Manning and Wheeler, Bonneville’s snakebit veterans, were especially wary. To minimize the chance of a breakdown, Manning reduced the stressful boost pressure on the turbocharger of his one and only, homemade, four–cylinder engine, which he claims to have spent a fortune developing.

The 63–year–old Wheeler, meanwhile, took his time getting to Bonneville, because he thought he was on the brink of tire failure. The bespectacled engineer, who’s been streamlining motorcycles since 1963, has been riding the same bike since 1991, a time when high–speed tires were readily available. But nowadays, tire manufacturers are out of the sport. They see little upside to the expensive development of products for a few speed demons who might turn around and sue if a tread or sidewall fails. Akatiff and Manning still have usable rubber. Wheeler, though, is down to the threads. Before coming to Bonneville this year, he’d decided to make only one set of runs.

On the morning of day three, Chris Carr, a small and fearless rider, slides into Seven, Manning’s overhauled bright–red streamliner. With Carr pulling on his driving gloves, Manning urges caution. “Go 325. If it feels good, 330,” he says. “We donÂ’t have to get it all at once.”

Then, for the umpteenth time in ManningÂ’s streamliner career, his bike suffers an equipment problem. But this one is rather pleasant.

According to the streamliner’s speedometer, Carr blasted through the trap at 335 miles per hour. But the instrument was off: He was actually going 354. His return trip clocks in at 347 miles per hour, giving Seven a two–way average of 351 and breaking the Ack Attack’s record by nearly ten miles per hour.

“I feel like a president,” Manning blubbers as a small cluster of cameramen and reporters close in around him.

Akatiff, watching from his pit, is stunned. “I thought, This canÂ’t be,” heÂ’ll tell me later.

First thing the next morning, Wheeler enjoys a memorable ride of his own. ·ˇâ€“Z–H´Ç´Ç°ě, his lime–green, Kawasaki–powered streamliner, goes a meet–best 355 miles per hour through the trap. But before he can rein in the motorcycle, the front tire disintegrates. Wheeler dumps the bike on its right side and skids for almost a quarter–mile. Fortunately, heÂ’s OK, but without a second run, he doesnÂ’t get the record.

Later, sitting in his pit and drinking a beer, Wheeler looks at his banged–up sled and tries to draw a positive from the wipeout. “Well,” he says, “now we know at what speed the tire blows up.”

UNTIL THE VERY END of the BUB meet, Akatiff believes he can come out on top. But that starts to seem doubtful. With a day and a half of racing to go, he discovers that a broken metal shaft has left a crucial part of the Ack Attack’s chain–drive transmission vulnerable. He has no replacement, but he does have superglue.

“LetÂ’s fill this thing up with J–B Weld and take the play out of the part,” says Akatiff, holding a fist–size metal housing. “Feel that bearing. I think it feels pretty good.”

Robinson doesnÂ’t care if Akatiff uses spit to keep the streamliner together—he just wants to race. “Rocky was with ManningÂ’s team for years and Denis couldnÂ’t get it done,” says his wife, Tricia, while a brooding Robinson puts his helmet into a car that will taxi him to the start line. “Now he feels like he did all the groundwork for their record. He wants it back.”

Soon, Robinson drives the Ack Attack down the course. The J–B Weld holds, but Akatiff, looking for more power, has played with the computerized engine–control system to the point that the engines run poorly. Robinson aborts.

The Ack Attack eventually runs down the track again, and again, but a transmission problem develops. On the morning of the last day, with 20 minutes left before the meet ends, one of the transmission chains breaks. Robinson coasts through the traps at 102 miles per hour. Thanks in large part to the perfect conditions, two streamliners have eclipsed CamposÂ’s record. But, in the end, Akatiff and Robinson have lost.

After the meet, Wheeler shrugs and decides that ManningÂ’s victory must have been fated. “Denis has had a lot of misfortune,” he says. “Perhaps he just deserved to have it go his way.”

ThatÂ’s not logical enough for Akatiff, who wonders whether CarrÂ’s run was legitimate. “Maybe a bird flew across the timing lights,” he theorizes. He then explains that heÂ’s already redesigned the Ack AttackÂ’s failed part and is pondering ways to squeeze more oomph from the twin Hayabusas. Meanwhile, he says, Robinson is raring to go, Wheeler is searching everywhere for new rubber, and Manning will obviously return. After all, itÂ’s his meet.

When I remind Akatiff that he was supposed to walk away from Bonneville after breaking the record, he corrects me. For him, land–speed racing is still unfinished business.

“I wanted to leave with the record,” he adds. “But this is actually great. Now we have a goal. ItÂ’s to go real, real fast.”