Tracing the Steps of Lost Explorers in Miserable, Beautiful Siberia

There's a reason exiles dreaded being packed off to Siberia. While retracing the path of a doomed 19th-century U.S. polar expedition in the Russian High Arctic, we encounter swarming mosquitoes, a few Kalashnikovs, an island lost in time, the burial site of ten brave men, and a haunting beauty like nothing we've ever seen.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

Da, Da, there it is,” Andrey says with a smile as he idles the outboard engine. He puffs a cigarette and points at a bulge on the horizon. “Amerika Khaya—America Mountain.”

Hampton Sides Siberia Podcast

��

I look where Andrey is pointing, but I’m distracted by clouds of insects. In this part of the Siberian Arctic, there are only two seasons: Winter and Mosquito. Right now we’re in the middle of Mosquito. The ravening swarms work their way under our clothes, dive into our mouths, clot our eyes and nostrils. On a nearby island, a few wild reindeer try to nibble the tundra moss, but they look tormented, their hides jumping with nervous tics.

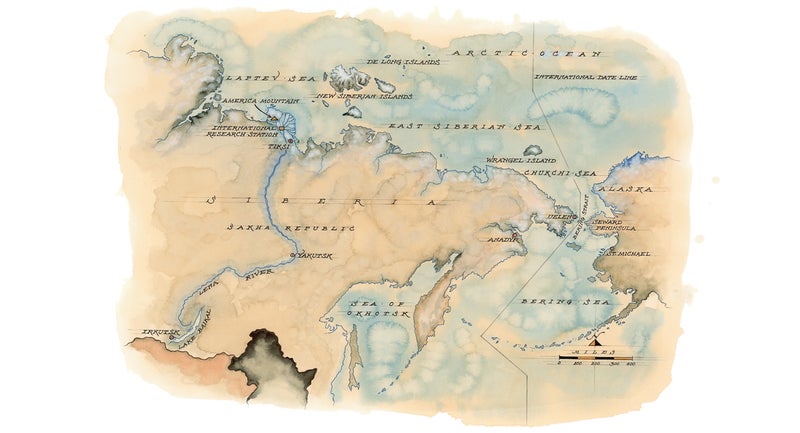

We’re 5,000 miles east of Moscow, nearly 400 miles north of the Arctic Circle, in the gale-smashed barrens where the great Lena River meets the Arctic Ocean. This is one of the world’s largest deltas, an estuarial snarl of river channels and silty islands that spreads out over 11,500 square miles of mostly uninhabited terrain. The Lena Delta is a (scientific nature reserve), one of the largest in Russia, set in the most remote territory of the Sakha Republic.

It’s mid-August, and I’m traveling with Andrey Kryukov, a former Russian soldier from Irkutsk who has worked on the Lena River for 22 years. Kryukov, who is in his forties, is the second-in-command of the Puteyskiy 405, a diesel riverboat that I’ve hitched a ride on for much of the past week. To navigate some of the shallower back channels of the delta, we left the Puteyskiy 405 around midday and ventured out in a banged-up johnboat. Andrey wears a black knit cap and army fatigues, and in case we should meet wolves or bandits or a rogue polar bear, he has a rifle slung over his shoulder.

We're swallowed in desolation, not a sound but the whine of the bugs. This is a Pleistocene tundra on a fantastic scale, an ancient emptiness that seems better suited for the mammoths, saber-toothed tigers, and woolly rhinos that once lived here.

Amerika Khaya is a small hog-backed mountain that rises 400 feet above the Lena’s floodplain of marshes and islands. It was also the burial site of ten Americans who perished in the Lena Delta during a then famous but now little-known polar expedition in the 1880s. It’s just a large hill, really, but on extra-clear days, Amerika Khaya is visible for a hundred miles, sometimes magnified by the refractions of the Arctic atmosphere.

Now we can clearly see it, but the mountain is surrounded by labyrinths of sandbars and channels of water. When we run aground for the fourth time, Andrey kills the engine in disgust. “Hop out,” he mutters, then drags the boat onto a sandbar. “From here ve vade.”

We start splashing across the puddles and stagnant ponds, swatting mosquitoes as we go. The mud sucks at our swamp boots—and yanks one of mine off my foot. Loons call in the distance. I can see the tracks of an arctic fox stitched across the sand. The water is bone-wincingly cold—somewhere in the low forties. When it suddenly rises to our waists, Andrey hoists his rifle over his head.

It’s past midnight when we reach dry land and hike to the base of America Mountain. Everything is suffused in the weird golden light of the Arctic summer, muted and thin, like the glow of a solar eclipse. We climb for an hour, stumbling over spongy terrain matted in stunted heathers and tiny red mushrooms. Here and there, bleached reindeer antlers are strewn over the ground.

We’re swallowed in desolation, not a sound but the whine of the bugs. This is a Pleistocene tundra on a fantastic scale, an ancient emptiness that seems better suited for the mammoths, saber-toothed tigers, and woolly rhinos that once lived here. No trees grow in the Lena Delta—we’re far north of the timberline—yet along the river channels are tangled graveyards of trees that have drifted a thousand miles from the dark forests of the taiga.

Seen from the air, the Lena Delta looks like the cross section of an enormous tumor that bulges far out into the Laptev Sea. Most of the year it’s covered in ice and snow, and even today, though Arctic flowers are blooming everywhere, it’s a frozen landscape: the permafrost, just below the surface, extends 2,000 feet belowground.

Throughout tsarist history, the upper Lena was known as a region where Russia banished her criminals: a prison without bars. Later, the Lena became the site of at least five Soviet gulags, the so-called River of No Reprieve. Surely this must be one of the loneliest spots on earth. Yet it’s also a land of awesome beauty—and a haunting site for a memorial to an expedition of forgotten American explorers.

I had come to the Russian Arctic to retrace a Gilded Age polar voyage that I was writing a book about. Three decades before Admiral Peary reached the top of the world, another American polar attempt, the United States Arctic Expedition of 1879, was all the rage. It was one of America’s first official efforts to reach the North Pole, sponsored by the U.S. Navy but paid for by James Gordon Bennett, the half-mad playboy publisher of the New York Herald who had sent Stanley to “find” Livingstone in Africa. The expedition, commanded by an indomitable Navy lieutenant from New York named George Washington De Long, carried the hopes of a young nation itching to make a mark on the world. The hold of De Long’s ship, the USS Jeannette, was crammed with the latest American inventions: a dynamo newly designed by Edison to generate light, as well as Bell’s telephones.

De Long, 34, planned to reach the North Pole via Alaska and the Bering Strait, a route that had never been tried before. (Up until that time, all polar attempts had concentrated on the Atlantic side, by way of Greenland or the Svalbard Islands north of Norway.) De Long actually hoped to sail to the pole. His expedition was predicated on the theories of an eminent cartography professor from Germany named August Petermann, who believed that the Kuro Siwo, a tropical current in the Pacific, swept through the Bering Strait and then softened up the ice, creating a “gateway” to a basin full of warm water—the Open Polar Sea, it was called—that many leading thinkers believed covered the earth’s dome.

Professor Petermann thought that all De Long had to do was burst through the Kuro Siwo–weakened ice pack to enjoy smooth sailing to the top of the world. De Long massively reinforced the hull of the Jeannette with thick timbers and an iron sheathing so that he could temporarily imprison her in the floes. His Ice Ark might drift for a few months, the thinking went, but eventually it would emerge from the pack and reach the tepid waters of the Open Polar Sea. If he succeeded, he would return a world hero.

Today it’s hard for us to understand how intensely curious people were in the 19th century to learn what was Up There. The polar problem loomed as a public fixation and a planetary enigma. The gallant, fur-cloaked men who ventured into the Arctic had become national idols. People couldn’t get enough of them.

Cheered by huge crowds, in July 1879, De Long and 30 carefully chosen men sailed with high hopes from San Francisco. His crew included a meteorologist, a naturalist, an ice pilot, an engineer, a few dozen seasoned seamen, and two Cantonese cooks from San Francisco’s Chinatown. “We have the right kind of stuff to dare all that man can do,” De Long wrote. Later that summer, the Jeannette passed through the Bering Strait and then on toward Siberia before aiming due north for regions mapped UNEXPLORED.

Today, De Long is one of the great forgotten heroes of American exploration. He discovered new lands, crossed a thousand miles of unexplored frozen ocean, and consigned a load of ridiculous theories—including the Open Polar Sea—to the dustbin. Though his voyage fell into spectacularly dire straits, De Long managed to avoid the three great banes of Arctic exploration: mutiny, scurvy, and cannibalism. He ably held his expedition together until the end and did all he could to ensure that his men came home.

The Jeannette was a sensation in its day, an American Shackleton story 35 years before the Endurance. It was chronicled in newspapers and was the subject of songs, poems, monuments, paintings, Congressional inquiries, and popular books. De Long’s expedition journals were bestsellers at the time. Yet most Americans today have never heard of him or the audacious voyage he undertook on behalf of his country. History, it seems, has passed him by.

I wanted to follow in the path of the Jeannette to experience something of what that epic journey was like. The end of the Cold War and the thinning of the ice brought about by climate change had made it possible to reach many of the places the Jeannette had voyaged, places that had effectively been off-limits for more than a century.

I planned to spend six weeks, taking a series of ships and boats, jets and prop planes, to trace De Long’s route from the Bering Strait to the Lena Delta. The distances and logistics were Siberian in scale. Most inconveniently, my route to the Bering Strait led not through Alaska but clear around the world. I flew to Moscow to secure an absurd number of government permits. (One official quizzed me: “By tradition, people are sent to those parts—you want to go there?”) Then I connected several flights east across eight time zones to the small port city of Anadyr, a town once governed by Roman Abramovitch, now the billionaire .

In Anadyr, the icebreaker Professor Khromov awaited. It was registered as a Russian vessel but owned by , a New Zealand adventure-travel outfit, and had a motley mix on board—scientists, eco-tourists, and a French documentary crew. The ship was bound for the Bering Strait, the Siberian coast, and a highly restricted Russian reserve set in the Chukchi Sea known as Wrangel Island.

We left Anadyr and were soon cruising past Alaska, but we couldn’t go there. Leaning over the rails, drinking a cold Baltika beer as gray whales breached in the distance, I gave a little wave to Sarah Palin and thought how ludicrous it was to have traveled 10,000 miles to look at my own country.

On his way to the Arctic, De Long had stopped at St. Michael, Alaska, where he bought furs, dogs, and other supplies—and hired two Inuits to serve as hunters and dog drivers. De Long found America’s newly purchased territory “a miserable place” with an air of decay fueled by liquor and exacerbated by the American fur and whaling industries.

Later in the day, we hopped into Zodiac rafts and sped to some cave-riddled cliffs along the Siberian shore, where we encountered hundreds of thousands of nesting birds. Puffins. Guillemots. Pelagic cormorants. Steller’s eiders. Ross’s gulls. They shrieked and chattered so loudly we had to shout to be heard. Agitated by our approach, their dive-bombing brethren nailed us with their guano. I’d never seen so much throbbing, jittery life crammed into one place.

On the faces of nearly everyone in the Zodiacs was the same look of delirious abandon. Out came the bird guides, up went the Nikons with their 800-millimeter zoom lenses. Everyone clicked away, giggling, ecstatic. “Look at the puffin! Aren’t you gorgeous!”

I hadn’t seen it coming: I would be spending the next two weeks on a ship positively infested with birders.

When the Jeannette passed along this coast, the expedition’s civilian scientist, a mousy, Smithsonian-affiliated naturalist named Raymond Newcomb, blasted one specimen of every bird species he encountered. Newcomb’s shipboard office became an abattoir, piled with decaying carcasses. “Natural History is well looked out for,” De Long wrote of his odd specimen collector. “Any bird that comes near the ship does so at the peril of its life.”

Captain Zhdanov and I stood looking at his chart of the Lena Delta. The delta was dizzyingly complex—and always changing. “Like most women I know,” he said, “The river likes to change her mind.” I could see how De Long and his contingent of men had gotten hopelessly lost here.

As we passed by the Diomede Islands and through the Bering Strait, following the international date line, I felt a kind of demarcational vertigo. Left was Asia and today. Right was North America and yesterday.* Behind us lay the Pacific Ocean, but the Arctic Ocean was just ahead. Beneath the ship, on the shallow seabed, was the Bering land bridge, across which, it is widely thought, waves of paleo-humans had wandered to the new world. This strait, a mere 53 miles across, has always been one of the planet’s great mytho-strategic chokepoints—a spot where currents collide, genes migrate, epochs touch. No wonder scientists of De Long’s day believed it was the natural gateway to the pole.

In years to come, the Bering Strait may serve as a different sort of gateway: the Russian government has been touting a plan to build a 64-mile tunnel that would connect Siberia to Alaska. The gargantuan conduit could cost upwards of $50 billion and, when finished, would be twice as long as Europe’s Chunnel. Theoretically, ordinary citizens could use it, though the tunnel’s main purpose would be transporting Siberian oil, gas, and electricity to the United States and Canada. Since Vladimir Putin’s incursion into Crimea, the project seems more fantastical than ever. But regionally, at least, the will is there on both sides of the strait.

Farther up the coast lies the tiny Chukchi town of Uelen. Russia’s easternmost settlement, Uelen (pop. 740) is set just south of the Arctic Circle along a gravel spit that backs up to a cold lagoon. An Orthodox church topped with a small onion dome rises over a grid of prefab buildings and weather-scabbed shacks. It’s essentially a marooned place—no roads lead from town, so the only way to get there is by helicopter or boat.

When we arrived, on a partly sunny afternoon with temperatures in the high forties, we were swarmed by giggling children. The village was in the midst of a festival. Hunters had recently caught a gray whale and butchered it on the rocks. Now the place was full of blubbery mirth, and a good bit of alcohol had made the rounds. Drums pounded as women in calico dresses performed ancient Chukchi dances. Athletic games were in full swing along the gravel beach: pole climbing, tug-of-war contests, weight lifting, wrestling.

The mistress of the games, a Yupik woman with a bullhorn, coaxed me and some of my birder friends to form a tug-of-war team. We won a few matches but were soon destroyed by a crew of burly young Ukrainian construction workers who’d come for the summer to erect prefab homes for the locals.

On the perimeter of all this festiveness lurked an air of official menace: four Russian soldiers, clutching Kalashnikovs, kept a close watch on the crowds. We’d been told we weren’t supposed to look at them, and that if we photographed them we’d be arrested, our cameras confiscated. In 2012, Putin declared this place a closed border zone. Visitors without special permits can expect to be imprisoned, fined, or deported. The soldiers inspected our paperwork and escorted us wherever we went. We were welcome, but not really. They made sure that after a few hours we returned to our ship and went on our way.

The next morning, we woke to find a huge ice field spread before us, obstructing our path to Wrangel Island. Most of the Arctic had seen a record amount of ice melt that summer, but not here. Our Russian captain gritted his teeth and said he’d never seen it so thick this time of summer. The Professor Khromov shuddered as we smashed through it. Great jagged cracks jigsawed out in front of us. Once, we rode up onto a floe and slid back down, grinding to a halt. Off the starboard bow, a polar bear stood on its hind legs and sniffed at us, mystified by the cumbersome thing crunching through its world.

Then the fog parted and there it was: Wrangel Island, 90 miles long, with broad valleys and mountains of virgin tundra gauzed in wisps of fog. Wrangel is a federally protected reserve some 80 miles off the northeast coast of Siberia. It’s a primeval place, supporting such an astonishing abundance of wildlife that biologists have called it the Galápagos of the far north. Wrangel is the largest polar bear denning ground in the world and boasts the largest population of Pacific walrus and one of the largest snow goose nesting colonies. It’s also the last place on earth where woolly mammoths lived.

In the late 1870s, when De Long was planning his expedition, Wrangel was still terra incognita. Some geographers thought it was a polar continent connected to Greenland. De Long’s idea was to try to land on Wrangel and explore it while using its coast as a ladder to climb toward his ultimate goal. If he reached the Open Polar Sea, he could sail for the North Pole in the Jeannette. If he didn’t, he could dash overland for the pole with dogs, sleds, and small boats.

But De Long never reached Wrangel. The Jeannette got locked in fast-moving ice, and he drifted past the island. “A glorious country to learn patience in,” De Long wrote. “It would take an earthquake to get us out.”

De Long didn’t know it yet, but this was the beginning of a long imprisonment: the Jeannette would drift northwest in the pack for more than 600 miles—and for nearly two years, without any link to the outside world. “I calmly believe,” De Long wrote, that “this icy waste will go on surging to and fro until the last trump blows.” He never found the Open Polar Sea, or a warm-water current that softened the polar pack. The Jeannette had been thwarted by a fortress of ice.

As we approached it, I could understand why cartographers once thought Wrangel might be a continent. It felt as though we’d reached the end of the earth.

An American relief vessel dispatched in 1881 to look for De Long did manage to land on Wrangel; the surrounding ice was unusually spare that summer. On board this rescue ship was the young naturalist John Muir, who was then a part-time San Francisco newspaper correspondent. Muir and his party raised an American flag on the beach and claimed the island for the United States, which is why certain hawkish groups in America today insist that Wrangel is rightfully U.S. soil and should be retaken. Muir found no sign of the Jeannette but was astounded by Wrangel’s pristine grandeur. The place seemed specially made for polar bears. Everywhere Muir looked he saw them. “Very fat and prosperous,” he wrote. “They are the unrivalled master existences of this ice-bound solitude.”

We landed on Wrangel Island by Zodiacs and clambered over a rocky shore littered with the bones of walruses and whales. Anatoli Rodionov, a big Russian preserve ranger in fatigues, met us at the beach. He was one of only four people who lived here year-round, and he seemed almost desperate for fresh human contact. He kept a can of bear spray and a flare gun holstered at his side. “Privyet, and welcome to Ostrov Vrangelya!” he gushed. “Thank God you have come!”

Anatoli led us over to Ushakovskoye, an abandoned settlement from Cold War times consisting of an old bathhouse and a few decrepit cabins, some of which had been dismantled for firewood. Nearby stood an ancient radar installation and a junkyard’s worth of mystery equipment from the Khrushchev era.

We spent five days on or around Wrangel, taking overland forays into the mountains, camping in tiny huts, passing over tundra whitened by vast flocks of snow geese. Anatoli introduced me to Sergey Gorshkov, who had been coming to Wrangel for much of the past decade to photograph polar bears and other animals. Pale and soft-spoken, with a goatee, Sergey retired from the oil business in Moscow in his thirties and picked up a camera. Nowadays, he ventures to extremely remote places—Kamchatka, Botswana, but especially Wrangel—and lingers for months at a time. He has since become a . “My life,” Sergey said, “is divided in two—before the camera and after. Photography is my sickness. My wife is ready to kill me.”

The Jeannette was a sensation in its day, an American Shackleton story 35 years before the Endurance. De Long's expedition journals were bestsellers at the time. Yet most Americans today have never heard of him or the audacious voyage.

Sergey invited me into his cabin, a ramshackle space piled with photographic equipment and canned goods he’d been living on for the past month. The windows were covered with metal grids spiked with six-inch nails to deter bears. After he showed me some of his work on an iPad, we took off on a Honda ATV, following a riverbed.

Sergey cut the engine and pointed. “There—in the river.” I splashed over to something half-submerged in the freezing ripples: a fossilized woolly mammoth tusk. “They’re everywhere on Wrangel,” Sergey said, beaming. “Wherever you go, elephant ivory!”

Sergey would be departing Wrangel with us in four days. “It’s difficult for me to leave,” he said. “I always think I may never come back, that it’s my last visit. This place gets to me.”

Nearly 600 miles northwest of Wrangel, the men of the Jeannette spent the spring and early summer of 1881 drifting in the ice pack. De Long’s men had plenty to eat and were generally healthy, though they were slowly going mad from boredom and inaction.

By then, De Long had given up on the idea of the Open Polar Sea—the whole concept, he said in his journal, was “a delusion and a snare.” But he had not given up on drifting to the North Pole. De Long discovered a group of islands and claimed them for the U.S. (They’re now known as the De Long Islands.) But in early June 1881, the Jeannette was mortally crushed by the ice. At one point, the decks bulged. At 4 a.m. on June 13, the ship plunged through the pack and sank to the bottom of the Arctic Ocean.

Cast out on the ice with their dogs, three open boats, and a few essential belongings, De Long and his 32 men had only one chance at survival: to drag their boats nearly 600 miles across the ice, hoping to find open water, and then sail for the nearest landmass—the central coast of Siberia.

They had only a few months to save themselves before winter set in. They would have to hunt for their own food while slogging over impossible expanses of crust and rubble and sludge. De Long’s maps showed that there might be settlements at the mouth of the Lena. Hoping to find a native village, he and his men aimed for the delta of one of the greatest rivers in the world.

The Lena River originates nearly 3,000 miles to the south of the Arctic Ocean, in a mountain range near Lake Baikal. As the river flows through the vast solitudes of Yakutia, it picks up tributary after tributary—the Kirenga, the Vitim, the Olyokma, the Aldan, the Vilyuy. The Lena is the world’s 11th-longest river, draining a vast swath of central Siberia. Because it flows north toward the Arctic, each fall the Lena freezes first at its mouth, developing a natural barrier that forces the water to fan out in a frantic search for other paths to the sea—which helps explain why the Lena’s delta is so extravagantly intricate, with untold thousands of islands and oxbow lakes.

This was the baffling landscape De Long and his men approached in their three open boats in September 1881. His crude chart labeled the country, simply, SWAMP OVER ETERNALLY FROZEN LAND.

To retrace this part of De Long’s journey, I left the Professor Khromov in Anadyr and flew west to a very different part of Siberia, the interior capital of Yakutsk—a booming hinterlands metropolis, built on gold and diamond riches, that is said to be the coldest city on earth. Then I took an iffy Brezhnev-era prop plane 1,000 miles north over the taiga and tundra to the coastal town of Tiksi. “Town” is a charitable word for this decaying, garbage-strewn collection of Soviet military barracks and empty slab apartment complexes. Technically speaking, Tiksi is an “urban locality,” the administrative center of the Sakha Republic’s Bulunsky District. During the Cold War, this place thrived as a staging base for long-range bombers. It basically was erected for the express purpose of annihilating my country.

Now Tiksi is mostly abandoned, although there is a climate research station nearby where scientists from around the world are studying the rapidly changing conditions in the Arctic. Tiksi is so remote, and the weather so harsh, that it’s nearly impossible to maintain infrastructure. The roads had turned to rubble. Pipes snaked across the tundra. Rusty container-ship modules were stacked everywhere, between scattered heaps of snarled wire, bent rebar, and busted concrete. Drinking vodka seemed to be the main pastime—I met a group of German engineers doing contract work there who had taken to calling the place Tipsy.

“Where are we?” I asked Victor, the taxi driver who drove me around town in a fumy Russian Uazik van. He was a dour, balding hardware-store owner who wore camos and had a rheumy hacking cough.

“Where are we?” Victor replied. “We are in the past.”

I had the privilege of being stuck in this existential wasteland for nearly a week. First I was required to obtain (what else?) more permits. The military officer inspected my papers and said, “State your reason for existence.” He had actually heard of George De Long and the Jeannette—a surprisingly large number of Russians have—but he’d never met an American who’d heard of them. Come to think of it, he said, he’d never met an American here at all. “Why such interest in De Longka now?” he wondered aloud as he studied my passport. “Americans want back islands De Longka discover—hmmm? Perhaps zat is real purpose here?”

He stamped my papers anyway and said, “Veelcome to Tiksi. You vill find it appalling place.”

Months earlier, I had made an arrangement by telephone to meet the director of the Lena zapovednik, who, for an exorbitant fee, had agreed to take me deep into the delta to find America Mountain. He’d told me he was the only person authorized to guide me there. I arrived in Tiksi a day before our departure date. But he was nowhere to be found when I visited the natural history museum he runs, a musty place crowded with mammoth bones, sagging specimens of taxidermy, and a small Jeannette expedition exhibit. An underling in his office said the director had gotten an offer to lead another trip into the delta—and that he was unreachable.

How long would he be unreachable? I asked.

“Vill be one month,” the man said. “Maybe two.”

I had to find an alternative, fast. That’s how I learned about the Puteyskiy 405, a commercial riverboat contracted by the government to work the delta every summer, gauging depths, removing snags, checking buoys, and generally keeping the main channels open for the big boat traffic. For a fee of a few thousand dollars, plus five cartons of cigarettes, I could hitch a ride.

The Puteyskiy 405 picked me up at an abandoned ship ten miles from Tiksi. The captain, Vitali Zhdanov, said he knew America Mountain well and had even hunted and trapped there when he was a boy. It was on the far side of the delta, he said, more than 100 miles away, and would take three days to reach.

Soon we headed out into the bay, then slipped into one of the Lena’s eastern branches, called Bykovskaya. The river was big and broad, and I felt as though I had landed in some Russian version of Twain’s Life on the Mississippi. The Puteyskiy 405 was a hard-working vessel, with a crew of ten and a fat gray cat named Marx. I was expected to help with the daily chores and galley responsibilities. This I was thrilled to do—anything to get me out of Tiksi.

We ate like kings: reindeer stew, smoked sturgeon, mounds of cabbage, and fresh fish hauled from the muddy river. I slept under the twilit sky and listened to the captain and his second-in-command, Andrey, as they laughed and smoked and rambled on through the night in the bold, beautiful Russian language. The world of the Lena enveloped me—its brackish smells, its plays of light, its endless patterns of snarls and eddies. I couldn’t have been happier.

We made a stop at a village called Bykovskiy. The dock had been wrecked by the ice, so getting ashore was a little tricky, involving a cat’s cradle of ropes and boards. The village was a jumble of slatternly houses, broken-down vehicles, and bored dogs. Planks were laid across the low swampy places, and rickety boardwalks had been built atop networks of steam and gas pipes.

People from around Bykovskiy were among those who helped save some of the Jeannette survivors when they finally reached the Lena by open boat and worked their way up its complicated delta. It was a village of Yakuts—seminomadic hunter-fishermen who built their world around the reindeer. In their facial features, the Yakuts resemble the Mongols, but their language is more closely related to Turkish. They had migrated here starting in the 13th century from the forests around Lake Baikal.

The men of the Jeannette found the Yakuts to be a proud and open-hearted people. They had spent centuries perfecting techniques for thriving in extreme cold; much of their independence came from their ability to live where no one else wanted to be. In these remote parts of Siberia, the expression went, “God is high up and the Czar is far off.”

People in Bykovskiy still talk about the De Long expedition. It’s a source of pride. At the school, I met a woman named Rabella Mukhoplyova—a Yakut administrator and teacher. “We know about De Longka,” she said. “We study him in our geography lessons. It is still hard to believe Amerikanskis came all the way here on a ship!” Rabella said the Yakuts around here thought the Jeannette survivors were a race of otherworldly men who had emerged from beneath the ice.

Bykovskiy was a shadow of what it used to be, Rabella said. The villagers had all but forgotten the ways of the reindeer, the walrus, and the whale. “In the seventies, there were dogs or reindeer next to every house,” she said. “Now everybody just drives snowmobiles.”

We continued deeper into the delta, working our way toward the river’s western branches. One afternoon we landed at an international research station, where a joint Russian-German team of scientists has been studying the condition of the permafrost. The station was a thriving compound of stackable sleeping modules powered by solar panels, wind turbines, and diesel generators. I met an intense young man named Alexander Makarov, from the polar geography department at the University of St. Petersburg. Researchers based here have been drilling in the soil at multiple locations around the Lena Delta to extract permafrost samples going back tens of thousands of years. “The permafrost is like a library archive of past climates, past environments,” Makarov said.

In recent times, as more permafrost melts during summertime, increased levels of methane—a greenhouse gas—have been escaping into the atmosphere. It’s a phenomenon common all over the Arctic, one that has led many scientists to make doomsday predictions. Some have called it the methane time bomb. Makarov is more guarded on the question. “Something is definitely happening out here,” he said. “The question is whether the changes are catastrophic. My opinion is that the permafrost is more stable than some people believe. This is a process of thousands of years, not decades.”

Back aboard the Puteyskiy 405, we continued west. Up on the bridge, Captain Zhdanov and I stood looking at his chart of the delta. The delta was dizzyingly complex—and always changing. Every year the spring flooding caused the channels to assume new courses. “Like most women I know,” Zhdanov said, “the river likes to change her mind.”

I could see how De Long and his contingent of men had gotten hopelessly lost here, staggering over this bewildering landscape for weeks without seeing a soul. “Here we … seemed to be wandering in a labyrinth,” De Long had written in the journal that he hauled in his weakening arms. “One does not like to feel he is caught in a trap.” Winter was setting in, but he could find no settlements. He was forced to make a cache and bury his meticulous meteorological logbooks from the ���ԲԱ�ٳٱ�’s two years in the ice. (These records were later recovered and are now to understand the condition of the late 19th-century ice pack.)

As their circumstances deteriorated, De Long was forced to slaughter his last dog. Then one of his crewmen died of frostbite. De Long wrote: “What in God’s name is going to become of us?”

The next morning, America Mountain slid into the Puteyskiy 405’s view, dancing in vaporous waves like an Arctic vision. In the refractions of the Siberian atmosphere, it sometimes looked like a castle, or a whale emerging from the sea, or the back of some enormous prehistoric beast. The Yakuts generally stayed away from America Mountain—it was said to be inhabited by witches—but it was the most dominant feature in the northwestern delta, a place so high it would never wash away in the Lena’s seasonal floods.

We drew as near as we could in the Puteyskiy 405. Then Andrey and I put out in the dingy.

In the spectral light, Andrey and I reached the top of Amerika Khaya. The survivors of the Jeannette expedition built a marker here in the Lena Delta in 1882, not just as a memorial and a crypt lofted safely above the floods, but as a rebuke to anyone who might pass this way and entertain doubts. We Americans were here, it seemed to say. Remember us.

De Long and his 32 men had stayed together for 700 miles and nearly three months as they retreated over the ice. But when they reached open water, a gale separated them. The survivors eventually found ten of their lost comrades, frozen by a broad bend in the river 20 miles from here, having died from exposure and starvation. The survivors wrapped the bodies in scraps of tent canvas and then hauled them by dog team to the top of this mountain. From lumber they’d found scattered along the river, they built a massive coffin—7 feet wide, 22 feet long, and 22 inches deep—held together by mortise-and-tenon joints. The bodies were placed inside it, with their faces turned toward the rising sun. Then the top of the coffin was hammered into place. Next, scores of lichen-splotched rocks were piled upon the coffin until the monument had assumed a pyramidal shape. From driftwood timbers, they constructed a large cross, 20 feet high with a 12-foot crossbeam. They carved out the inscription—“In memory of the officers and men of the Arctic steamer ‘Jeannette’ who died of starvation in the Lena Delta, October, 1881.”

Their somber work was completed on April 7, 1882. In 1883, the bodies were disinterred and shipped by reindeer team, horse-drawn sleds, and train all the way to Moscow, in an elaborate funeral procession jointly orchestrated by the U.S. Navy and the Russian government. Then they were shipped to New York, where the Jeannette dead were celebrated as national heroes and “martyrs to science.”

The Jeannette monument had scarcely changed from the lithograph sketches I’d seen from the 1880s. The original cross—or perhaps a refurbished one, it was hard to tell—was still there. A tattered Russian flag snapped in the wind. Next to the cross stood a little stone obelisk that had been erected by some historically minded group from Tiksi. At the base of it was a metal box. I unclasped it and found messages from the handful of people who had visited over the decades—a few Russian and German climate experts, a Japanese polar scientist. They’d left trinkets, cheap jewelry, cigarettes, airplane bottles of liquor, and paper money that had yellowed over time. These items, it seemed, were meant not merely as offerings, but as things that might prove useful to the long-dead adventurers in their Arctic heaven.

I scribbled a note of praise to the men of the Jeannette, for their sacrifice, for their ingenuity, for their integrity. “Nil desperandum,” I said. Never despair. It was a catchphrase throughout De Long’s journals, his motto to the end. I placed the note in the box.

I stared off at the iceless Arctic Ocean to the north, which giant freighters and Maersk container ships have increasingly been using in summertime as a northeast passage. One day soon, the climatologists tell us, an Open Polar Sea may really exist. Maybe De Long wasn’t crazy after all; he was just off by 140 years.

Andrey and I were savoring the ghostly light, high above the bogs. We made a picnic of vodka, sturgeon, and reindeer jerky. At around 1 A.M., we finally decided it was time to go. As a gift to the dead, Andrey placed a shiny new bullet in the metal box and clasped it shut. “In case they’re hunting,” he said, flashing a smile of tobacco-stained teeth. “In case they’re hungry.”

Then he raised his rifle and fired three rounds into the air. The shots rang out over America Mountain and fell on the braided bends of the Lena Delta, scattering a flock of geese.

Editor at large Hampton Sides's book about De Long's expedition, In the Kingdom of Ice: The Grand and Terrible Polar Voyage of the USS Jeannette, is published this monthy by Doubleday. .