Northern Lights Hunting with This Indigenous Tracker Was the Most Moving şÚÁĎłÔąĎÍř of My Life

Joe Buffalo Child has a deep connection to the auroras, which his people, the Dene, believe carry messages from their ancestors. We headed into the boreal forest seeking light.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

Joe Buffalo Child grew up beneath the northern lights, but one starry winter night in particular remains etched in his memory. He was six years old and camping with his grandparents to monitor the family trapline, a 50-mile stretch of snares set for rabbits and muskrats in the snowy boreal forest outside Yellowknife, the capital of Canada’s Northwest Territories. Slipping out of the cozy tent, his breath fogging as he gazed skyward, it wasn’t long before Buffalo Child found what he was seeking: “It was stars, stars, stars, then—boom! The aurora’s there,” he told me, his eyes sparkling at the flashback.

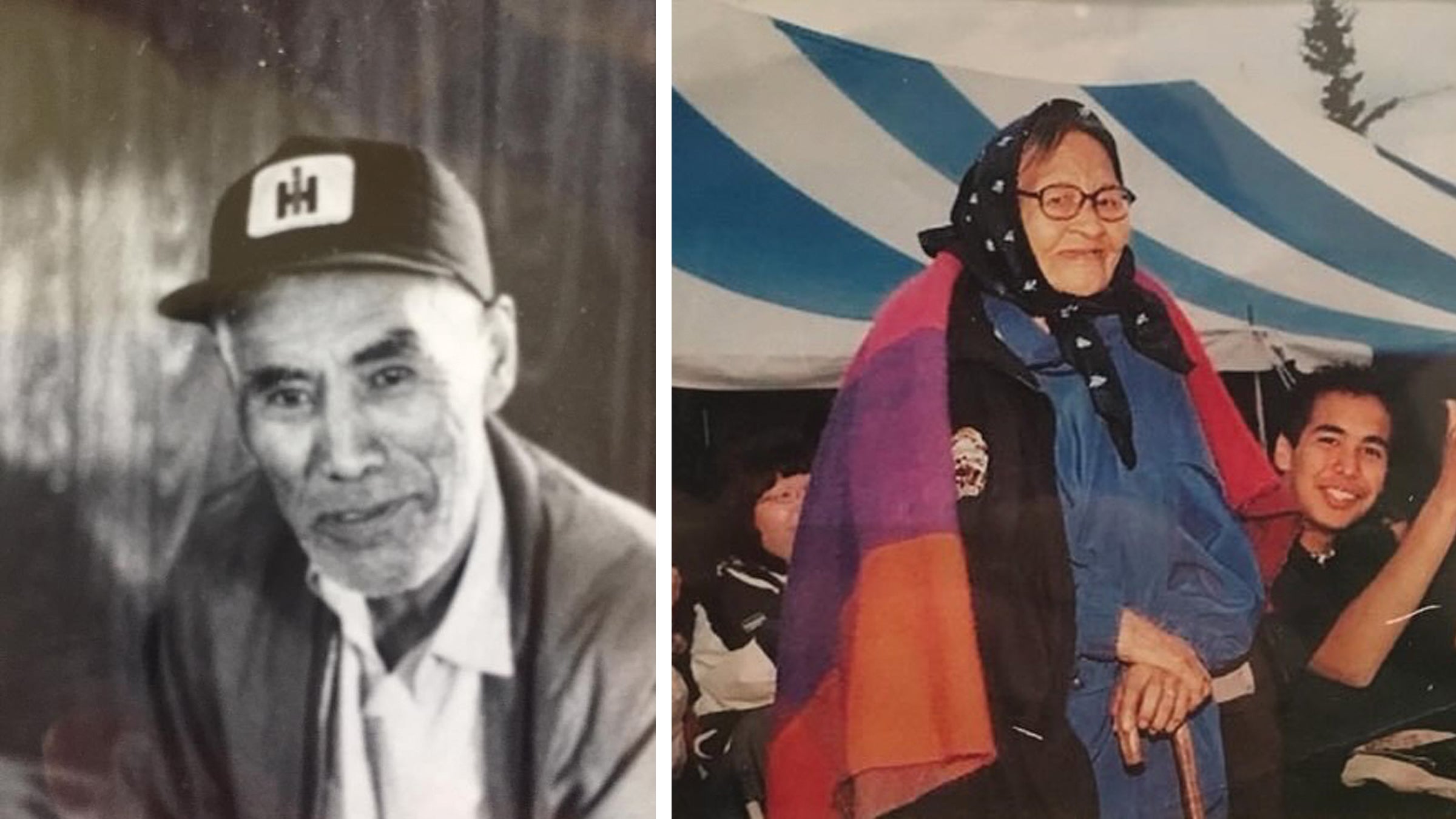

On trapline trips like these, learned about the many ways nature was tied to the traditions of his people, the , who have inhabited central and northwest Canada for over 30,000 years. By day, his grandfather took him hunting or fishing—outings that came with important lessons, like how to predict an approaching storm by studying the movement of the clouds or the height of a seagull’s flight. Come dusk, bathed in the gas lamp’s honey glow, his grandmother shared spiritual beliefs, like how Buffalo Child’s beloved tie-dyed sky dance, known in the Denesuline language as ya’ke ngas (“the sky is stirring”), carried messages from his ancestors.

“I was on the land under the aurora even as a baby,” he said. “The aurora’s always been part of our life.”

This deep knowledge of nature and cultural connection to the night sky were foundational to his future as a professional northern-lights chaser and guide for his company . Now 60 years old, Buffalo Child has spent nearly two decades sharing his aurora-tracking abilities with those willing to make the journey up to Yellowknife. He is considered one of the most well-known aurora hunters in North America.