The vanlife movement has awoken a new generation of┬áAmerican road-trippersÔÇömyself included. The Instagram hashtag #vanlife has been tagged over 4.77 million times. As a lifestyle, it offers a new vision of the American dream, and itÔÇÖs one that allows me to live in nature. But┬áas it turns out, this lifestyle is not necessarily better for nature.

Two years ago I moved into a vehicle to escape the hustle of humanity and concrete that enmeshes the Washington, D.C., area, where I worked as a full-time writer for NASA.┬áIÔÇÖm now a freelance writer and photographer, spending the seasons following the sun like a migratory bird, often amid a flock of like-minded individuals living in trucks, vans, and cars.

The more I roam, the more IÔÇÖve begun to question the impact of my lifestyle. With a footprint of 24 square feetÔÇöa bit smaller than a full-size┬ábedÔÇöthe 2006 Honda Element I call home is one-hundredth the size of the average American household and far smaller than any┬átiny house. A┬ámodest┬áhouse typically takes less energy to heat than a traditional house, which is often the largest contributor to a carbon footprint. But in the case of my mobile tiny home, the gas it uses to deliver me to far-flung places makes my carbon footprint disproportionately larger than my physical one. Every time I fill up the tank, I wonder:┬áAm I harming the places I love to live more so than I did when I was living in a house?

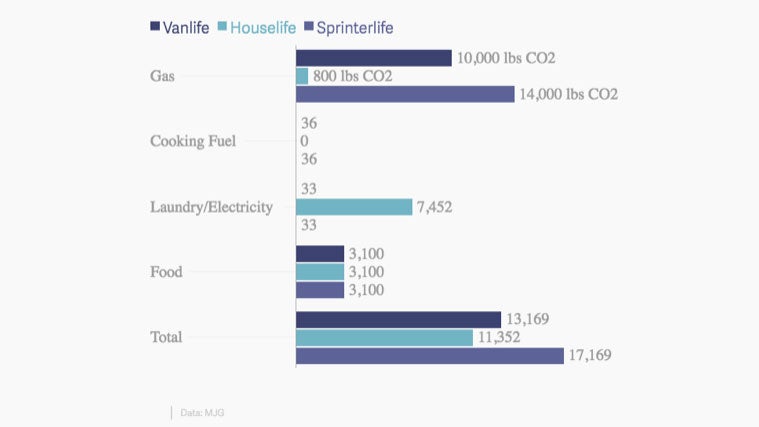

I sat down with a pen, paper, and a calculator. Driving, which constitutes , was clearly going to be the largest contributor to my emissions, so I started there. Since every five┬ámiles per hour driven above 60 miles per hour┬á, IÔÇÖve adopted a tortoise-paced driving style. I eke out an average 25 miles to the gallon, but I cruise some 12,500 miles in a year, just less than the average AmericanÔÇö. Annually, this deposits around 10,000 pounds of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Beyond gas, I also contribute 33 pounds of carbon dioxide a year from doing laundry.

Adding in my relatively sustainable vegetarian diet, which according to a , adds in around 3,100 pounds of carbon dioxide from growing and transporting food, plus 36 pounds of carbon dioxide for cooking fuel, my total emissions tip the scales at 6.6 U.S. tons of carbon dioxide, considerably above the global average of 5.5 tons.

We would┬áneed more than two earths to sustain us if everyone lived like me, according to the┬á. Hardly what youÔÇÖd call sustainable.

Before setting off on the road, I lived in the suburbs of D.C., sharing a house with two friends. We strove to live conscientiouslyÔÇöcomposting, recycling, turning down the heat, and bike commuting. Looking back on our electricity bills and the miles I drove then, I calculated my carbon emissions for that lifestyle at 5.6 tons of carbon dioxide. Including other things a house requires, namely sewage and waste disposal, add in around an additional 1,100 pounds of carbon dioxide annually. By living in a vehicle, I am actually doing worse by the environmentÔÇöliterally a ton worse.

At the same time, my circumstances of the way I lived in a traditional house and the vehicle I drive arenÔÇÖt typical. According to ┬áconducted by the World Bank, the average American goes through 18 tons of carbon dioxide per yearÔÇömuch larger than my own house footprintÔÇöand, similarly, many vanlifers drive homes with compatible or worse fuel economies than my Honda Element. In fact,┬áa Sprinter vanÔÇöthe oft-desired luxury liner of vansÔÇöwould create 40 percent more emissions over the same miles compared to my own bright-red box on wheels, given the Sprinter vans┬álower mileage and use of diesel.

Skeptics will point out that since 1988 come from just 100 companies. Indeed, major industries are huge contributors to emissions, much more than any of us individually. At the same time, these industries exist to serve us. By reducing our own consumption, we reduce the need for these companies, and by holding these companies responsible, we can add pressure on them to invest in renewables.

I mulled over these numbers as I watched the sunrise from , amid the Santa Catalina range in southern Arizona. The air was crisp, and a multitude of twinkling lights far below in Tucson winked out just after the stars as the morning gained momentum. Soon dozens of vehicles would be zipping by, taking families up the mountain for a Sunday picnic or hike.

IÔÇÖve taken the first step in being┬áconscientious of my impact, but the next stepÔÇöactually making changesÔÇöwill prove to be much harder. Since driving is 75 percent of my footprint, IÔÇÖll focus on reducing my mileage by staying put longer and carefully planning out routes. IÔÇÖll also commit to keeping a close eye on tire pressure and regular checkups, which can improve fuel economy. By┬áeating locally, I can save driven. So from now on, look out for me living vanlife in the slow lane. In addition to joining the , which promotes local and traditional foods, IÔÇÖll be pioneering a Slow Driving movement.