The Worst Kind of Type 2 Fun in the Arctic

In an excerpt from his new book, ‘Into the Thaw,’ Jon Waterman vividly depicts one of his most painful expedition moments ever

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

More than 40 years ago, the then park ranger Jon Waterman took his first journey to Alaska’s Noatak River. Captivated by the profusion of wildlife, the rich habitat, and the unfamiliar landscape, he spent years kayaking, packrafting, skiing, dogsledding, and backpacking in Arctic North America—often alone for weeks at a time. After three decades away from the Noatak, he returned with his 15-year-old son, Alistair, in 2021 to find a flooded river and a scarcity of the once abundant caribou. The Arctic had warmed nearly four times faster than the rest of the world.

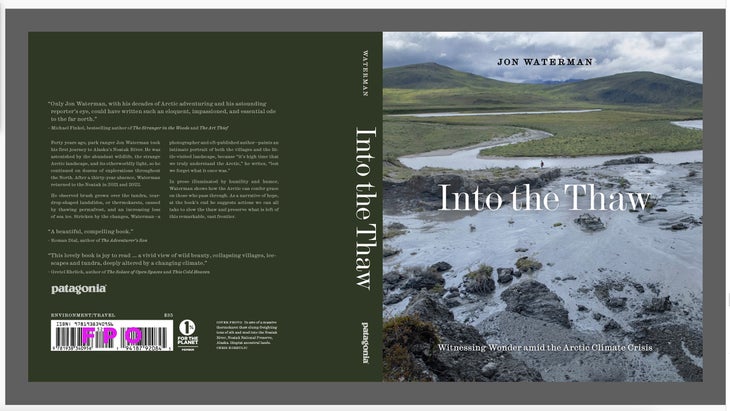

The next year, 2022, Waterman took a last journey to document the changes. The following is excerpted and adapted from his prologue in Into the Thaw: Witnessing Wonder amid the Arctic Climate Crisis (Patagonia Books, November 12).

A former ranger in Rocky Mountain�����Ի� Denali national parks, Waterman is the author of 17 books, including (National Geographic Books), In the Shadow of Denali, Kayaking the Vermilion Sea, Running Dry, and Arctic Crossing. He has made five films about adventure and wild places.

If you buy through our links, we may earn an affiliate commission. This supports our mission to get more people active and outside. Learn more.

The below is adapted from Into the Thaw: Witnessing Wonder amid the Arctic Climate Crisis.

A Certain Type of Fun, July 10-12, 2022

My hands, thighs, and calves have repeatedly locked up in painful dehydration cramps, undoubtedly caused by our toil with leaden packs in eighty-degree heat up the steep streambed or its slippery, egg-shaped boulders. After my water bottle slid out of an outside pack pocket and disappeared amid one of several waist-deep stream fords or in thick alders yesterday, I carefully slide the bear spray can (looped in a sling around my shoulders) to the side so it doesn’t get knocked out of its pouch, an action I will come to regret. Now, to slake my thirst, I submerge my head in Kalulutok Creek like a water dog.

Kalulutok Creek would be called a river in most parts of the world. Here in Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve, amid the largest span of legislated wilderness in the United States, it’s just a creek compared to the massive Noatak River that we’re bound for. But in my mind—after we splash-walked packrafts and forded its depths at least 30 times yesterday—Kalulutok will always be an ice-cold, wild river.

It drains the Endicott and Schwatka Mountains, which are filled with the most spectacular granite and limestone spires of the entire Brooks Range. One valley to the east of us is sky-lined with sharp, flinty peaks called the Arrigetch, or “fingers of the outstretched hand” in Iñupiaq.

As the continent’s most northerly mountains, the sea-fossil-filled Brooks Range—with more than a half-dozen time-worn peaks over 8,000 feet high—is seen on a map as the last curl of the Rocky Mountains before they stairstep into foothills and coastal plains along the Arctic Ocean. The Brooks Range stretches 200 miles south to north and 700 miles to the east, where it jabs into Canada. Although there are more than 400 named peaks, since the Brooks Range is remote and relatively untraveled, it’s rare that anyone bothers to climb these mountains. My river-slogger companion, Chris, and I will be exceptions.

We carry a water filter, but it would be silly to use it. We’re higher and farther north than giardiasis-infected beavers and there is no sign of caribou. The creek is fed from the pure ice of shrunken glaciers above and ancient permafrost in the ground below. In what seems like prodigious heat for the Arctic, the taps here are all wide-open.

Thirty-nine years ago, I decided to learn all I could about life above the Arctic Circle. As a climber, I traded my worship of high mountains for the High Arctic. I felt that unlike the study of crevasse extrication and avalanche avoidance—you couldn’t just read about the Arctic or sign up for courses. You have to go on immersive journeys and figure out how the interlocked parts of the natural world fit together. Along this path, acts of curiosity out on the land and the water can open an earned universe of wonders. But you must spend time in the villages, too, with the kindhearted people of the North to make sure you get it right. And you can’t call the Arctic “the Far North”—it is “home” rather than “far” to the many people who live there.

So, after twoscore of Arctic journeys, in the summer of 2022, I’m on one more trip. I could not be on such an ambitious trip without all the previous experiences. (The more I learn, it sometimes feels like the less I know about the Arctic.)

But this time the agenda is different. I hope to understand the climate crisis better.

Chris Korbulic and I are here to document it however we can. Since my first trip above the Arctic Circle in 1983, I have seen extraordinary changes in the landscape. Only three days underway and we’ve already flown over a wildfire to access our Walker Lake drop-off point. And yesterday we trudged underneath several bizarre, tear-drop-shaped landslide thaw slumps—a.k.a. thermokarsts—caused by the permafrost thaw.

In much of Alaska, the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP) says that permafrost thaw from 2005 to 2010 has caused the ground to sink more than four inches, and in places to the north of us, twice that. The land collapses as the permafrost below it thaws, like logs pulled out from beneath a woodpile. AMAP believes this will amount to a “large-scale degradation of near-surface permafrost by the end of the twenty-first century.” Roads and buildings and pipelines—along with hillsides, Iñupiat homes, forests, and even lakes—will fall crazily aslant, or get sucked into the ground as if taken by an earthquake.

On this remote wilderness trip, we don’t expect a picnic—known as Type 1 Fun to modern-day adventurers. A journey across the thaw on foot and by packraft for 500-plus miles won’t resemble a backcountry ski trip or a long weekend backpack on Lower 48 trails. We have planned for Type 2 Fun: an ambitious expedition that will make us suffer and give us the potential to extend ourselves just enough that there will be hours, or even days, that won’t seem like fun until much later when we’re back home. Then our short-circuited memories will allow us to plan the next trip as if nothing went wrong on this one. An important part of wilderness mastery is to avoid Type 3 Fun: a wreckage of accidents, injuries, near-starvation, or rescue. We’ve both been on Type 3 Fun trips that we’d rather forget.

Today, to get Chris, a caffeine connoisseur, to stop, I simply utter, “Coffee?” His face lights up as he throws off his pack and pulls out the stove. I pull out the fuel bottle. Since Chris isn’t a conversational bon vivant, I’ve learned not to ask too many questions, but a cup of coffee might stimulate a considerate comment or two about the weather. As I fire up the trusty MSR stove with a lighter, we crowd around and toast our hands over the hot windscreen as if it’s our humble campfire. We’re cold and wet with sweat and we shiver in the wind. But at least we’re out of the forest-fire smoke—this summer more than two million acres have burned in dried-out Alaska.

Today, with the all-day uphill climb and inevitable back-and-forth route decisions through the gorge ahead, we’ll be lucky to trudge even five miles to the lake below the pass. Why, I ask myself, as Chris puts on his pack and shifts into high gear, could we not have simply flown into the headwaters of the Noatak River instead of crossing the Brooks Range to get here? I heave on my pack and wonder how I’ll catch Chris, already far ahead.

Shards of caribou bones and antlers lie on the tundra as ghostly business cards of a bygone migration, greened with mold, and minutely chiseled and mined for calcium by tiny vole teeth. We kick steps across a snowfield, then work our way down a steep, multicolored boulderfield, whorled red and peppered with white quartz unlike any rocks I’ve seen before. As rain shakes out of the sky like Parmesan cheese from a can, we weave in and out of leafy alder thickets while I examine yet another fresh pile of grizzly feces. I stop to pick apart the scat and thumb through stems and leaves and root pieces. This griz appears to be on a vegetarian diet.

“Hey, bear!” We yell the old cautionary refrain again and again until we’re hoarse. I hold tight to the pepper spray looped over my shoulder to keep it from grabby alder branches.

A half mile farther the route dead-ends so we’re forced to descend into the gorge again. With Chris 20 yards behind, I plunge step down through a near-vertical slope of alders and play Tarzan for my descent as I hang onto a flexible yet stout branch, and swing down a short cliff into another alder thicket. A branch whacks me in the chest and knocks off the pepper-spray safety plug. When I swing onto the ground, I get caught on another branch that depresses the trigger in an abrupt explosion that shoots straight out from my chest in a surreal orange cloud. Instinctively I hold my breath and close my eyes and continue to shimmy downward, but I know I’m covered in red-hot pepper spray.

When I run out of breath, I squint, keep my mouth closed, breathe carefully through my nose, and scurry out of the orange capsaicin cloud. Down in a boulderfield that pulses with a stream, I open my mouth, take a deep breath, and yell to Chris that I’m O.K. as I strip off my shirt and try to wring it out in the stream. I tie the contaminated shirt on the outside of my pack and put on a sweater. My hands prickle with pepper.

Then we’re off again. As we clamber up steep scree to exit the gorge, my lips, nasal passages, forehead, and thighs burn from the pepper. The pepper spray spreads from my thighs to my crotch like a troop of red ants, but I can hardly remove my pants amid the incoming storm clouds and wind. With the last of the alders below us, we enter the alpine world above the tree line. By the time we reach the lake, the drizzle has become a steady rain. I’m nauseous and overheated underneath my rain jacket with the red pepper spray that I wish I had saved for an aggressive bear instead of a self-douche. Atop wet tundra that feels like a sponge underfoot, we pitch the Megamid tent with a paddle lashed to a ski pole and guy out the corners with four of the several million surrounding boulders left by the reduction of tectonic litter.

I fire up the stove and boil the water, and we inhale four portions of freeze-dried pasta inside the tent. We depart from wilderness bear decorum to cook outside and away from the tent because it’s cold and we’re tired. Chris immediately heads out with his camera. His eyes are watery from just being within several feet of me.

I’ve been reduced like this before—wounded and exhausted and temporarily knocked off my game. So, I tell myself that this too will pass, that I’ll get in gear and regain my mojo. That maybe, I can eventually get my shy partner to loosen up and talk. That we will discover an extraordinary new world—the headwaters of the Noatak River—from up on the pass in the morning. And that I will find a way to withstand my transformation into a spicy human burrito.

Snow feels likely tonight. It’s mid-July, yet winter has slid in like a glacier over the Kalulutok Valley.

I am too brain-dead to write in my journal, too physically wiped out and overheated in the wrong places to even think of a simple jaunt through the flowers to see the view that awaits us. I pull down my orange-stained pants and red underwear, grab a cup filled with ice water. I try not to moan as I put in my extra-hot penis and let it go numb.

Type 2 Fun for sure.

Jon Waterman lives in Carbondale, Colorado. An all-round adventurer, he has climbed the famous Cassin Ridge on Denali in winter; soloed the Northwest Passage; sailed to Hawaii picking up microplastics; dogsledded into and up Canada’s Mount Logan; and run the Colorado River 1,450 miles from source to sea. He is a recipient of the National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship and three grants from the National Geographic Society Expeditions Council. Into the Thaw is available to purchase from Patagonia Books and for pre-order on Amazon for November 19.

For more by this author:

A Former National Park Ranger Reveals His Favorite Wild Places in the U.S.