OREGON

As I helped my kids pack for a road trip from our home in Portland to the twin southern-Oregon wonders of Crater Lake National Park and Oregon Caves National Monument, an item in the paper caught my eye. The day before, a reliable witness had reported seeing Sasquatch during his family’s visit to the Oregon Caves. “I know what a bear looks like,” I read, quoting the man for 12-year-old Tom and nine-year-old Mary, “and that was no bear.” The kids looked up thoughtfully.

“Is there only one Bigfoot?” Mary asked. “Or do they have families?”

“Mary, there isn’t any Bigfoot,” Tom said, with a big brother’s air of authority. “Sasquatch is only a myth.”

“…I smelled a pungent, overpowering odor…,” I read.

“Give me that newspaper,” my wife, Patricia, said with a glare.

We set out on a sunny July morning, driving east on U.S. 26 beside the flank of Mount Hood along the Chain of Fire, the magnificent row of volcanic peaks that runs the length of Oregon. The landscape opened; the loamy aroma of fir gave way to the sharp perfume of sage and manzanita. We stopped for a picnic on the banks of the trout-rich upper Deschutes River that borders the Connecticut-size Warm Springs Indian Reservation. The dry heat penetrated our rain-soaked Willamette Valley bones.

After lunch, we continued south on U.S. 97, resisting the temptation to stop at the excellent High Desert Museum near Bend, which we’d explored on previous road trips. Two hours later, we stood on the northwestern rim of Crater Lake, and the fidgety discomfort of the car trip’s last hour evaporated. Mary and Tom gazed out at the vast crystal waters.

“You mean the top of the mountain just blew off?” Mary asked.

“The volcanic explosion was 42 times more powerful than the Mount St. Helens eruption,” Tom informed her.

Mary considered for a moment. “Lucky thing,” she said.

For the next few days that blue eye beamed at us; the lake formed an oceanic presence that somehow seemed larger than the ocean. We gloried in the view from our room at the rambling, recently restored Crater Lake Lodge. Apart from the lodge, which often books up a year in advance, the park didn’t feel at all crowded. Seems that most visitors settle for driving in, taking a few snapshots, and then drilling back to Interstate 5.

We wanted to explore the park in greater depth. We drove between surreally huge leftover snowdrifts—banked 12 feet high on either side of Rim Drive—to a spectacular overlook hanging above the Phantom Ship, a basalt formation that, in profile, bears a striking resemblance to the cloud-ship in Peter Pan. At park headquarters, three miles from the rim, we scrambled over the boulder- and trillium-festooned Castle Crest Wildflower Trail.

The next morning we rose early to take the boat tour leaving from Cleetwood Cove. The steep, mile-long Cleetwood Trail is the only route between the crater rim and the water. Seen from the lake surface, the caldera’s basalt and lava walls shimmered, and the water changed color with each shifting wind and drifting cloud. Wizard Island, a volcanic plug that, in an eon or so, could grow into another fire-spewing peak, jutted up like Merlin’s cap. Normally you can disembark at the island to fish, picnic, and hike, but high winds prevented our boat from docking that morning. Tom, who’d packed his rod and reel, was briefly disappointed. The captain redlined the return route to the cove, and sheets of ice-cold lake water spumed over the bow, leaving us all shivering but ecstatic.

Exiting the park, we drove 150 miles southwest to the coastal mountains and Oregon Caves National Monument. The serpentine marble caverns are a striking complement to the caldera. After absorbing so much dazzling light at the lake, our eyes welcomed the caves’ ghostly darkness.

We checked into the comfortable and slightly eccentric Oregon Caves Lodge, which features a surprisingly good restaurant (with a real stream trickling through it) and, even more surprising, a retro soda fountain serving national-class milkshakes. None of the 22 rooms has a TV. Up in these silent, remote hills, a TV would be as out of place as a Wal-Mart. In the morning we followed our tour guide into the phantasmagorical depths, wearing hard hats for protection and heavy coats (don’t forget yours) against the prevailing 40-degree chill. The two-hour tour—a guaranteed kid-pleaser—took us slithering and scrambling over winding, spectrally lit paths and into giant rooms furnished with stalactites and stalagmites. Parents always forget which formation points up and which points down. Kids always seem to remember.

We emerged from underground into warm, clear sunshine. There were two ways back to the lodge, a quick ten-minute downhill stroll, and a steeper, more scenic route. The kids readily assented to the high road. Normally, Tom or I walk point in our family hikes. But that day, Mary insisted on taking the lead. When we stopped for water, I asked her why.

“So I can be the first one to see Sasquatch,” she replied. She thought for a moment and then added, “I guess I won’t mind if Tom smells him first.”

ROAD MAP

CRATER LAKE LODGE, built in 1915, was extensively restored six years ago and is open from mid-May through mid-October. Double-room rates range from $115-$160; loft rooms, which have two queen beds, cost $225 for four people. Reservations should be made at least six to eight months in advance of a summer arrival; call 541-830-8700. Crater Lake National Park information: 541-594-2211; www.nps.gov/crla.

BOAT TOURS of Crater Lake depart from Cleetwood Cove, a ten-mile drive from the lodge, several times daily from late June through mid-September, weather permitting, and last about two hours. For more information, check with Crater Lake Lodge.

OREGON CAVES NATIONAL MONUMENT is located 20 miles east of Cave Junction, Oregon. From I-5 at Grants Pass, head southwest on U.S.199 to Oregon 46. For information, call 541-592-2100; www.nps.gov/orca. For reservations at Oregon Caves Lodge ($95 for one or two people, $15 each additional person, kids 6 and under stay free), call 541-592-3400.

VIRGINIA: The Caves of the Shenandoah Valley

Our four-year-old daughter Hayley started talking about caves not long after she started talking. She’d study pictures, ask questions, and create her own virtual cave experience beneath the comforter. Her fascination rekindled my own childhood interest in spelunking, and I promised to show her the real thing.

The Shenandoah Valley of western Virginia is pocked with caves and campgrounds, so that’s where we headed. Bounded by the Blue Ridge and Appalachian Mountains, Interstate 81 runs up the valley, paralleling the Shenandoah River. These are scenic foothills, largely rural, with much of the land under preservation. The defining characteristic is “karst topography,” which is a fancy term for cave country. Caves are produced when underground springs dissolve limestone bedrock over millions of years, leaving behind subterranean chasms. Eight commercial caves line a 150-mile stretch along I-81 between Salem and Front Royal, Virginia.

First we test the waters with a weekend trip to Luray Caverns, the most famous cave in the East. Hayley adores the experience, especially listening to melodies played on the “stalacpipe,” a natural underground marimba. Next we try Endless Caverns, which is rawer and less tourist-inundated. She is captivated by such spectacles as Diamond Lake and Fairyland, but is a little overwhelmed by the strangeness of the environment. When the guide asks if there are any questions, Hayley raises her hand. “Do you know the way out of here?”

On our next foray, we decide to take on four caves in a weekend. Our great Virginia cave crawl begins with the Caverns at Natural Bridge, where the main lure is the 215-foot rock bridge that Thomas Jefferson proclaimed “the most sublime of Nature’s Works.” But we’re here for the caverns, the deepest commercial cave on the East Coast (347 feet), which is still being carved by moving water and is home to bats, salamanders, millipedes, crickets, and a strange species of beetle.

On the way in, Hayley registers uncertainty (“I wanna go back, I don’t like caves”) but does a 180 upon our exit (“I love caves,” she exults). In between, she ogles eight-million-year-old flowstone, peers into depthless solution holes, and happily receives a “cave kiss”: a drip of water from overhead. But she whimpers when we’re plunged into “total cave darkness,” that moment on every cave tour when the lights are extinguished. It is a blackness so profound that if you were to stay there for two weeks you’d be temporarily blinded when reintroduced to light.

En route to Shenandoah Caverns, we take a blue highway instead of the interstate, and Hayley gazes out at the Virginia countryside: fields of hay in circular bales, farm ponds, rolling hills and distant mountains, and lots of spotted cows.

Shenandoah Caverns is another big hit. Not only does it feature stunning geology—glistening cataracts of flowstone, sparkling curtains of crystalline calcite, and formations that suggest fried bacon and Darth Vader—but Hayley is given a lucky penny by the guide and told that as long as she holds fast to it, nothing will scare her. From this moment on, she is the very picture of bravery. At a mirror-smooth pool called the Wishing Well, Hayley is given another penny, which she tosses in. “I wished for a cow,” she confides. Near the end of the tour, she makes her customary inquiry—”Do you know the way out of here?”—and then adds, “Just teasing!”

Crystal Caverns, our next stop, is the smallest Virginia show cave and the least flashy in terms of lighting and effects. It’s appealing because it’s so intimate and natural. To Hayley’s delight we are each given a flashlight. In pre-Colonial times the cave was used by Native Americans who quarried arrowheads from a vein of hard, black limestone in a chamber they regarded as sacred. Rumors abound of auras and spirits, and PBS has been out to investigate. “If you believe the psychics, there is some hot stuff going on in here,” says the guide.

As we traipse through, our guide points out likenesses suggested by the daunting formations: a giant’s coffin, a reposing alligator, the dome of the U.S. Capitol (“It looks like vanilla ice cream!” shouts Hayley). Crystal Caverns is renowned for its honeycombed crystalline rimstone and diamondlike calcite crystals. Certain passages are tight and the cave is raw, but Hayley is elated. “I like it more here than all the caves,” she announces, waving her flashlight. “I want to go here every day.”

Now a confirmed cavehound, Hayley enters Skyline Caverns—her fourth of the weekend—as if it were a McDonald’s Playland. She charges around the labyrinthine curves and passageways and even welcomes total cave darkness without shrieking. She also takes a shine to the 16-year-old tour guide, literally running circles around him in the Cathedral Room.

Lacy calcite formations called anthodites are unique to Skyline Caverns. They hang from the ceiling like suspended snowflakes. Streams flow through, one of them home to a sightless cave beetle. With its high-ceilinged chambers and narrow passages, the cave resembles an underground Grand Canyon. Hayley trots through the catacombs like a kid riding a broomstick pony, completely comfortable with the notion that she is 260 feet underground.

A spelunker is born.

ROAD MAP

Along the I-81 corridor in western Virginia, you can realistically tour two caves a day with kids in tow. Each tour lasts roughly 60–90 minutes. Here’s an itinerary for a three-day, two-night trek that hits every cave and campground that we did. It moves from south to north, from Natural Bridge to Front Royal, a distance of 125 miles.

DAY ONE starts with a tour of the Caverns at Natural Bridge (Exit 175; 800-533-1410; www.naturalbridgeva.com). Then drive 90 miles north to Luray Caverns (Exit 264; 540-743-6551; www.luraycaverns.com). Spend the night on a mountain in nearby Shenandoah National Park (for information, call the park office at 540-999-3500) at Matthew’s Arm or Big Meadows campground; both are located off the scenic Skyline Drive, which is just ten miles eastof Luray via U.S. 211.

ON THE SECOND DAY, take in Endless Caverns (Exit 257; 540-896-2283; www.endlesscavern.com) and then proceed to Shenandoah Caverns (Exit 269; 540-477-3115; www.shenandoahcaverns.com). Camp that night on the banks of the Shenandoah River at Shenandoah River State Park (540-622-6840; www.dcr.state.va.us/parks/andygues.htm), accessible from I-81 by exiting onto I-66 (Exit 300) and then taking U.S. 340 (Exit 6) south to Bentonville.

AFTER BREAKING CAMP ON THE THIRD DAY, head five miles north on U.S. 340 to Skyline Caverns (Exit 13; 540-635-4545; www.skylinecaverns.com). Then finish off your spelunking expedition at Crystal Caverns (Exit 298; 540-465-5884).

UTAH: The Canyons of Zion and Escalante

Our small station wagon fills up quickly as we prepare for our first car-camping expedition in the American West. Even when it’s full we can’t stop loading—coolers, baseball gloves, a second tent, extra plastic bowls for bowl racing. We’re not used to such license. For our family, gear discipline is usually enforced by the cargo limitations of backpacks or sea kayaks. But now the highway beckons to our stuff. Wedging water bottles and hiking guidebooks into the front seat, I glance into the kid zone in back, which is brimming with Legos, ‘N Sync CDs, and hardbound Harry Potters. Maybe the reason we can’t stop loading is we’re heading from California to a new landscape: the canyonlands of southern Utah. If there prove to be no stores in the region, we’ll be ready. No Mormon wagon train was ever so well prepared.

The trip starts happily enough, at least in the front seat. My wife laughs hysterically every time she turns and sees me gazing out at the farm fields with what I take to be a faint Bruce Willis smirk. I have shaved off my beard for the first time in our 16 years together. But discouraging words are heard from the back, where sleeping bags and cooking pots keep avalanching onto the heads of Emily (nine) and Ethan (five). In Reno, abandoning the bearded father’s spartan ways, I buy a storage bin and mount it on the roof. Miraculously, I still can’t see out the back.

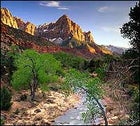

We are another day crossing Nevada, rising and falling along a highway whose sagebrush loneliness is diminished only by too frequent signs proclaiming it “The Loneliest Highway in America.” We turn south into Utah and soon approach the immense range of the Colorado Plateau, split like a ripe mango by canyons of red and yellow rock. It’s mid-March. We’re gambling that spring will arrive in the canyons by the time In this part of the world, you can actually drive deep into the backcountry. But we begin our trip in the well-marked splendor of Zion National Park, where a single busy campground is open for the early season. There is a fair hubbub in red-rock Yosemite—college students camping on their break. Though we see no animals on our midday hikes, we keep our senses sharp by counting Old Navy logos.

The sunny spring days are not too hot for hiking. The kids surprise us, chugging up two miles of (paved!) switchbacks to the top of a sheer precipice called Scout Lookout. This is mountains-with-handrails country, but as parents we’re willing to overlook the breach of Edward Abbey ethics. From the lookout, the trail continues a half-mile across exposed sandstone slabs to a promontory known as Angel’s Landing. Worried we’re pushing too far, we lead our kids slowly onto the face, clutching a heavy chain bolted to the rock and pausing occasionally to let the college students clamber past. As I gaze into the valley 1,300 feet below, Ethan tugs at my shirt and asks, in a tone that seems only mildly curious, “Is this the end of my life?” We turn back.

From Zion we drive east into the mountains on Utah 12, through gray skies and a dusting of snow. In the town of Escalante we turn south on Hole-in-the-Rock Road, a 58-mile pioneer route that once led Mormons across the Colorado River and now dead-ends at Lake Powell. We have entered the Grand Staircase- Escalante National Monument, created by President Clinton in 1996 to acclaim from environmentalists and outcries from Utah Republicans. The gravel road follows a high bench parallel to the Escalante River, a wild tributary of the Colorado. It is eerie to gaze across miles of redrock-and-juniper country, with its Alaska-size remoteness, and see little hint of the trapdoor landscape of canyons falling away to the east.

In contrast to busy Zion, here we rarely encounter another car. We congratulate ourselves on beating the crowds. “That’s because it’s snowing, Dad,” observes Emily. True enough, an occasional snow squall sweeps the horizon. “Operation Desert Storm,” we dub our spring vacation, and pretty much abandon plans for an overnight backpacking trip.

No matter. For families like us, there are countless “primitive” car-camping sites and turnoffs to reach side canyons of the Escalante. We choose several, relying on guidebooks and maps from the BLM office in town. At night we tent alone, read aloud by lantern, and listen to coyotes under a big black sky.

One cool gray afternoon we hike into Spooky and Peek-a-boo Canyons, slots of whimsically sculpted sandstone so narrow we have to turn sideways to squeeze through. The canyons are giddy gymnasiums that have us scrambling over chockstones, wedging past small pools of water, and even squeezing up chimneys 20 feet to climb out on the rock above.

On another day, the kids and I hike partway down Harris Wash, a regular Hopalong Cassidy movie set complete with a handful of grazing cattle. We follow a wide sandy bottom through cottonwoods into a zone of desert-varnished caves, hidden pools, and rock climbs with exploding sandstone handholds. Ethan finds a heart-shaped rock to bring back to his mother. Backing out of a box canyon, I step into a dry creekbed and feel my boot sink. “Quicksand!” I yell, dramatically leaping free to impress the kids. Rounding some trees, we discover something that makes my showing off redundant: a dead cow buried to its shoulders in a quicksand wallow. “Is there such a thing as slow sand?” Ethan wants to know. The next morning, when a local rancher rides up to our camp to ask what we’d seen down the canyon, I feign casualness as I describe our find, while Ethan hides behind my leg and gazes up wide-eyed at the cowboy on horseback.

We return to a highway campground for our last night. Above Calf Creek Recreation Area, a five-and-a-half-mile round-trip hike leads through a high-walled canyon with Anasazi pictographs and ruins. The trail dead-ends at Lower Calf Creek Falls, a refrigerated grotto where a 130-foot cataract makes a too-hot afternoon cold enough for sweaters. On the way back, we find a riffling stretch of Calf Creek just right to launch our plastic eating dishes in a bowl race, an essential family tradition. Then we throw them back on the pile of gear that’s soon to be headed home.

ROAD MAP

ZION NATIONAL PARK can see rainy days in March, but sunshine is common in spring and not as unrelenting as in summer. Watchman Campground (150 summer sites, $14) has 45 sites open all year; South Campground ($14, or $16 with electricity) is open April through October. Call 800-365-2267 for camping reservations. Visitors must now take a free shuttle bus to gain access to the main canyon. More information is available from the park office (435-772-3256) or at www.nps.gov/zion.

GRAND STAIRCASE- ESCALANTE NATIONAL MONUMENT covers almost 2 million acres in southern Utah. For information on hikes and campgrounds, both developed and primitive, call the Visitor’s Center at 435-826-5499 or log on to www.ut.blm.gov/monument. The town of Escalante, along Utah 12 between Bryce Canyon and Capitol Reef National Parks, has a few small grocery stores and motels. A great source of information and gear in town is Escalante Outfitters (435-826-4266), which also provides after-hiking pizza at its Esca-latte Cafe.

OF THE SEVERAL CANYON-HIKING GUIDEBOOKS available, we especially liked Utah Hiking, by Buck Tilton (Foghorn Press, 1999), which describes hiking through Spooky Canyon as “crawling through the belly of a sandstone snake.”