I grew up in southern Arizona, homeland of the Apache leader Geronimo, who evaded 5,000 U.S. Army troops there in 1886. But when I began planning a hiking and mountain-biking foray into north-central Wyoming, I quickly learned that Portal, Arizona, has nothing on the Bighorn Mountains as a landscape steeped in dramatic and violent history. Beginning at the Montana border and extending south for a hundred miles, the Bighorns overlook many of the most famous sites in Western history, including the Little Bighorn Battlefield and Hole-in-the-Wall (Butch and Sundance’s hideout).

But it was to lesser known, yet equally pivotal, sites within the foothills of the Bighorns that I was attracted. On the east flank of the range was Fort Phil Kearny, where Red Cloud’s Sioux warriors fought the army to a humiliating retreat in 1867. Near there the brash Captain William Fetterman, who boasted that with 80 soldiers he could defeat the entire Sioux nation, disregarded orders and chased a band of warriors straight into an ambush, dying along with all of his men. Leading the Indians that day was a young warrior named Crazy Horse. These and other setbacks convinced the U.S. government to leave northern Wyoming and its three forts on the east side of the Bighorns. When gold was discovered in the Black Hills a few years later, the army returned to crush the tribes once and for all.

For all the region’s fractious history, its transformation of the range from battle ground to recreation area occurred surprisingly early. By the 1890s the grasslands around the mountains were suffering from overgrazing, and ranchers were driving large herds into the mountain meadows and fighting with each other over rights to the high country. Partly in response, President Grover Cleveland established the Bighorn Forest Reserve in 1891; today it’s called Bighorn National Forest and encompasses more than 1.1 million acres. Grazing was curtailed and a new industry evolved: the dude ranch. Suddenly the mountains were the focus of more peaceful pursuits, with the alpine lakes of Tongue River Canyon and the deep gorge of Shell Canyon attracting hunters and fishermen—both of whom still come here 100 years later, along with backpackers, mountain bikers, cavers, and hang gliders.

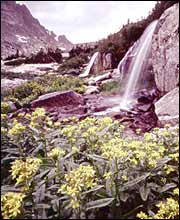

When I arrived at the Bighorns, I headed straight for their highest point: 13,165-foot Cloud Peak, in the heart of Cloud Peak Wilderness, a 189,000-acre chunk of the south-central region of Bighorn National Forest that’s mostly above the tree line. I got a fast lesson in the vagaries of high-country weather. Although summer solstice was at hand, an early-June snowstorm had dumped several feet of fresh powder over the high country. As I started up the Solitude Loop Trail, a 45-mile path that circles the range’s highest peaks, I realized that Cloud Peak would be unattainable. But I was determined to get as far into the wilderness as I could to grab at least a glimpse into the citadel of bare peaks. Five miles up the trail the tree line—a stunted patchwork of subalpine firs and Engelmann spruces—was already behind me. Ahead lay 50,000 or so acres of alpine tundra, a spare landscape of rock, spongy groundcover, and ice that’s the highest major life zone in the Lower 48. There was also a lot of snow. The trail continued up a gently sloping valley and in front of me a bare scree slope ascended to a promising bluff. The temperature was dropping and more clouds were rolling in so I decided to take the most direct path up it; 15 minutes later I stood on top. An enormous cirque plunged 300 feet down to a frozen aquamarine lake and then sloped up and away to a sawtoothed ridge. Stacked southward beyond that were the outlines of Black Tooth Mountain and Cloud Peak itself. I sat under a cornice until snowflakes obscured the view. Then I turned tail and ran, and a frigid sleetstorm swatted me down the last half-mile of trail.

The Bighorns rise up dramatically when approached from the east—jagged, snow-capped peaks jutting out from the Great Plains. From the west, U.S. 14 corkscrews up from Bighorn Basin through high meadows and past alpine lakes. Inhabitants of the nearby towns of Sheridan and Buffalo treat them as a very large backyard. Given the number of times I heard “Bighorns” mentioned as a favorite place for biking, hiking, and fly-fishing, you’d suspect the mountains would be overrun. That they’re not is a testament to their scale: The national forest gets about 2.5 million visitors each year, but there’s still ample room for a healthy population of moose, elk, black bears, and mountain lions, as well as smaller beasts like marmots, pine martens, and pikas (grizzly bears were extirpated by the 1940s).

I had planned to spend several days hiking the wilderness area, but given the unexpected weather conditions, I swapped sports. The morning after the storm, I tossed my mountain bike into the car and headed southwest out of Sheridan. Eleven miles from town I reached Red Grade Road, a well-maintained stretch of dirt that switchbacks rapidly above expansive grasslands into lodgepole pine forest, skirts the northern boundary of the Cloud Peak Wilderness, and links up with U.S. 14 some 30 miles later. I pitched my tent at the Ranger Creek Campground, hopped on the bike, and headed farther up the road—and almost immediately ran into the only other riders I would see the entire week. Mike and Dave, who both work at Sheridan cycle shops, were forthcoming with their Bighorns bike-trail knowledge. They’d been riding in the area for two years, they told me, and still hadn’t repeated enough routes to have favorites yet.

After three days of riding I was convinced that you would wear out several bicycles before exhausting the trail system here. Even on day trips from Sheridan you can pedal for weeks without crossing your track, either doing loops or, with a shuttle, any of several brake-scorching descents into the Powder River Valley. Load up panniers and it’d be possible to ride off-road through the national forest all the way from U.S. 14 south to U.S. 16—between 40 and 70 miles, depending on your route.

My quadriceps, however, were ready for a break, so the next day I drove west out of Sheridan on U.S. 14, across the spine of the mountains to the Medicine Wheel trailhead. More a blocked-off road than a trail, it leads a mile and a half to the best-known of many archaeological sites in the Bighorns. The Medicine Wheel is a circle of limestone slabs and boulders 75 feet in diameter, with 28 spokes radiating from a central hub, and six cairns arranged around the circumference. Its origins are a mystery, except that a piece of wood recovered from one of the cairns was dated to 1760. Its purpose is also a mystery, although in the absence of concrete history—or even explanations from local tribes—theories run the gamut from plausible (spokes representing days in the lunar month, cairns the six visible planets) to the unlikely (connections with Aztec sun worshippers). What is known is that travois tracks worn into the surrounding earth indicate pilgrimages over many generations. And modern Native Americans of several tribes—Sioux, Cheyenne, Crow, and Blackfoot, among others—still consider it a sacred site, evidenced by the prayer bundles I found. If the people who built the wheel were seeking inspiration, they certainly picked the right spot—an exposed bluff at 10,000 feet, with endless views west over the Powder River Basin and north into Montana.

I saved the most poignant site on my list for last. Wyoming 193, just north of Buffalo, leads north to the visitor’s center at Fort Kearny. I walked from the fort site three miles to the stone obelisk marking the place where Captain Fetterman and his men met their end in 1866. From the Fetterman Monument I stopped finally at a much more modest site, little visited, known as the Wagon Box Fight. Here, shortly after the Fetterman defeat, a force of just 32 soldiers held off a vastly superior force of Sioux warriors. Although it was a tiny victory in a doomed campaign, it was significant for the new weapon that ensured the soldiers’ survival—the breech-loading rifle, capable of firing five times as fast as the old muzzle loaders. It was a symbol of the military technology that would shortly spell the end of the free Sioux Nation.

Snow falls year-round in Wyoming’s high country, but summer in the Bighorn Mountains is usually dry and warm—ideal for hiking and biking. Expect daytime temperatures in the seventies and nighttime lows in the forties from mid-July through mid-September.

GETTING THERE

Flying into Sheridan puts you just ten miles from the Bighorns. But for a great historical and cultural primer on the region, fly into Cody and visit the Buffalo Bill Historical Center, a Western museum, then drive 50 miles northeast on U.S. 14 to Sheridan.

GETTING AROUND

Budget Car and Truck Rental in the Cody airport (800.527.0700) offers four-door compact cars for around $45 a day throughout the summer. At the Sheridan airport’s Enterprise Rent-A-Car (800.736.8222), four-wheel drives go for a weekly rate of $450.

CAMPING

The Bighorn National Forest has no fewer than 30 campgrounds with varying fees and amenities. Contact the Tongue River Ranger District in Sheridan (877-444-6777) for reservations.

LODGING

In Cody, you can stay at the stately Irma Hotel, built by Buffalo Bill himself in 1902 (doubles start at $96; 307-587-4221). Downtown Sheridan has a Best Western (doubles, $83; 307-674-7421), but you should try to take advantage of the fact that this is dude ranch country. In the mountains, 25 miles southwest of Sheridan, you’ll find the rustic Spear-O-Wigwam Ranch (307-655-3217; www.spear-o-wigwam.com), where Hemingway finished writing A Farewell to Arms. Daily rates start at $160 per person, including meals, horseback riding, and other activities.