We push up out of the forest and onto the pass, and the landscape sheds its skin. Shrugging free of moss and thickets and the dirt itself, bare granite stands braced against the wind and the sun and the last drops of rain, all beating down at once. Below us spreads a Patagoniac’s fantasy: skies racing with heavy clouds; unclimbed, unnamed 10,000-foot peaks; waterfalls carving down hillsides of 450-year-old lenga beech trees; and the Cachet Glacier, glowing Slurpee blue, its pale cliffs calving ice into the dark cocktail of a lake called Cachet Dos.

Patagonia

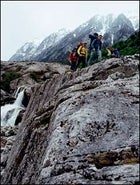

SHAKEDOWN CRUISE: Trekkers near Lago Cachet Dos, on the new Aysén Glacier Trail

SHAKEDOWN CRUISE: Trekkers near Lago Cachet Dos, on the new Aysén Glacier TrailPatagonia

POWER SPOT: The Colonia Glacier, with Lago Cachet Dos in the foreground

POWER SPOT: The Colonia Glacier, with Lago Cachet Dos in the foregroundPatagonia

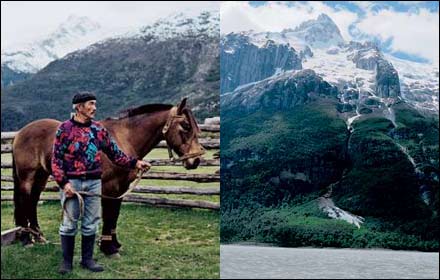

SOUTHERN LIVING: Clockwise from top left, the Sol de Mayo ranch; Nate Simmons on the Neff Glacier; Jonathan Leidich, sipping mate; hiking through a lenga forest in Laguna San Rafael National Park

SOUTHERN LIVING: Clockwise from top left, the Sol de Mayo ranch; Nate Simmons on the Neff Glacier; Jonathan Leidich, sipping mate; hiking through a lenga forest in Laguna San Rafael National ParkPatagonia

It’s October, early spring in southern Chile’s Aysén region, and our ragged group of ten has been bushwhacking for three days, crashing through dense thickets of feathery coigue and ñirre trees, pulling on slick roots, spiny calafate bushes giving way beneath our boots. We’ve navigated horse-deep rivers, sustained sunburns and stomach flu, and cramponed over a wide, thick glacier. Now we stand panting on the pass, dazed by the switch from myopic forest to far-out vista.

“Uh, Jonathan,” says Sun Valley, Idaho–based outfitter Scott Douglas. “This isn’t a trail.”

The announcement doesn’t seem to faze Jonathan Leidich, our guide, who hooks his thumbs in his pack straps and beams. The 31-year-old founder of Patagonia ���ϳԹ��� Expeditions (PAEX), based in Coyhaique, Chile, Jonathan is an expat Coloradan who’s spent much of the past eight years taking clients down the 40,000-cubic-foot-per-second rapids of Chile’s nearby Río Baker. Between trips, he’s hacked a world-class trekking route out of these high glacial valleys, the first trail through a remote, rugged national park called Laguna San Rafael. But before his first big group of clients arrives, he’s invited down five friends from the States—including Scott, the one who told him about this area 12 years ago—and four guides-in-training. We’re all here to test-drive the trail. Cool vision. Trouble is, none of us can see it yet. We look out and see trackless wilderness. Jonathan sees sustainable yurts and hot showers. He sees the Aysén Glacier Trail, a seven-day, 52-mile hut-to-hut work in progress that will be the first major new trail in South America since the iconic Paine Circuit, 300 miles to the south, sprang up in Torres del Paine National Park in the late fifties. Trekkers have made the 60-mile Paine one of the most famous walks in the world, but with up to 400 hikers a day, it’s saturated. The Aysén Glacier Trail, Jonathan hopes, will become a northern alternative.

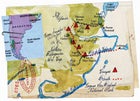

Extending 6,718 square miles from the Andes to the Pacific over the entire 1,622-square-mile Northern Patagonian Ice Cap, Laguna San Rafael National Park is nine times bigger and a hundred times emptier than 700-square-mile Torres del Paine. And unlike the Torres del Paine circuit, the Aysén Glacier Trail will stay empty. Only 17 trekkers, 12 guided and five independent, will be allowed to set out each day—all controlled by PAEX. Because the trail begins and ends on Jonathan’s own land, because it passes through local gauchos’ ranches on easements that Jonathan has personally negotiated, and because Jonathan is building the six yurt camps himself, the Corporación Nacional Forestal (CONAF), Chile’s national-park service, has awarded PAEX an exclusive concession to operate the trail, the first arrangement of its kind in the country. The deal is designed, in part, to provide an alternative economy in a wild region that still sees more resource extraction than ecotourism.

For Jonathan, setting all this in motion has been no big deal, really: It’s merely involved five years of bargaining with the Chilean government; the purchase of two ranches, 1,381-acre Palomar and 2,105-acre Sol de Mayo, on Laguna San Rafael’s eastern edge; a sustained charm offensive eloquent enough to convince the gaucho populations of two river valleys, Valle Soler and Valle Colonia, to allow trekkers to pass through their land; the navigation of a constantly changing four-and-a-half-mile-wide route over the Neff Glacier; and the humping-in of enough tarps and tents and pots and pans and spoons and sleeping mats for six campsites. And then there’s the boat. Establishing a crossing over the five-mile-long Lago Colonia—a glacial drainage that cuts off land access to the national park from Sol de Mayo—required the helicopter airlift of a 27-foot fishing boat, a two-week oxcart march to haul in the outboard motor, and a floatplane rental to fly in a new motor when the first one broke.

“Yeah, maybe I should just bag the trail,” Jonathan jokes. He looks at Scott. “So,” he asks, “are you sold on it yet?”

Scott looks around. No camps. No showers. No yurts. It’s clear that Jonathan is way ahead of himself. But as all of us look over these peaks, we can’t help being floored by possibility.

“Yeah,” says Scott. “I’m sold.”

CHARLES DARWIN STARTED IT. The Voyage of the Beagle, his 1845 account of spending five years as a naturalist aboard Captain Robert FitzRoy’s ship, was the first advertisement for Patagonia, luring adventurers and outlaws to the bottom of the world. Butch and Sundance holed up in Cholila, Argentina, in 1902; in the early thirties, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry threaded his plane through the Andes’ high passes, delivering mail; and Paul Theroux proved in his 1979 bestseller The Old Patagonian Express that the name itself exerts a due-south pull.

But it was the late British travel writer Bruce Chatwin who cemented the myth. His 1977 travelogue In Patagonia became a backpack staple, depicting an outpost of exiled Nazis and eccentric Welsh farmers living where the wind rattled “like an unloaded truck banging over a bridge.” Some of Chatwin’s hosts later said he’d made most of it up—a fitting charge for a place that shimmers on the frontier between geography and romance.

Patagonia encompasses most of the great tail of South America, from roughly 39 degrees latitude down across the Northern and Southern Patagonian ice caps, over the granite massifs of Fitz Roy and Torres del Paine, and on to the northernmost islands of Tierra del Fuego. On the Argentinian side of the Andes, the land is flat and dry; on the Chilean, clouds traveling 5,000 miles across the Pacific dump up to 200 inches of annual rainfall on a tangle of forests and fjords.

The result is the perfect stomping ground for a certain kind of rugged individualist. Iconoclastic climber Yvon Chouinard named his clothing company Patagonia, inspired by his 1968 road trip in a Ford van from California to 11,073-foot Fitz Roy. Over in Argentina, Ted Turner bought a monster estancia on a river full of monster trout. Tom Brokaw lit out for Chile as soon as he left his anchorman’s desk last year.

So far, gringos have not loved Patagonia to death, but the wave is moving south. Rafters and kayakers and fly-fishermen have claimed the towns of Esquel and Bariloche in Argentina, the whitewater of Chile’s Río Futaleufu, and, down by Fitz Roy, the Argentinian village of El Chalten. Next up seems to be the Chilean region of Aysén, an area four times the size of Vermont, with an emptiness reminiscent of America’s West Coast 125 years ago: 91,500 people dispersed over 42,000 square miles, 72 percent living in the region’s capital, Coyhaique. Aysén sees only 18,000 ecotourists a year, compared with 85,000 in Torres del Paine and 60,000 around the Fitz Roy massif.

And the prices! Ten thousand dollars for an acre and a half on 714-square-mile Lago General Carrera. Got a couple million? That’ll buy you a fixer-upper in downtown Aspen—or your own little national park down here. One afternoon in Coyhaique, before we headed south to join Jonathan, I got the locals’ tour from an expat Californian named Peter “Cado” Avenali, founder of Salvaje Corazon outfitters and cofounder of the Patagonia Foundation, an environmental nonprofit. Cado, 58, is the kind of strong-jawed adventurer who stays three steps ahead of the tourist stampede. We were driving southwest along the rapids of the Río Mañihuales; here and there, a broad black hat emerged from a dip in the landscape, rising to reveal a gaucho and a sturdy pony. Cado sat at the wheel of his Nissan pickup, trying to think of one bad thing.

“Well, there are no snakes,” he said. “Nothing that bites. There’s no poison oak. Wine’s cheap and delicious. The lamb’s great… .” He was stumped.

“You know, when I grew up in California,” Cado said, “climbing at Camp 4 in Yosemite in the sixties, there was nobody there. And in 40 years, that’s all gone. Patagonia represents to us what there was. In America, it’s a good lifestyle and all, but I can’t live with those restrictions. You start to feel like an animal—a big cat—with your back up against the wall.

“And there’s more left,” he continued. “Patagonia is an area that’s the size, almost to the kilometer, of California, Oregon, and Washington, with a little bit of Idaho combined, and it has about 1.8 million people. It’s like the old days of exploration. But there’s no easy way to get to this stuff. You have to want it.”

That’s what made the Aysén Glacier Trail so alluring. We were headed off the map, it seemed, or at least out of the guidebook. Opening my copy of Lonely Planet’s Trekking in the Patagonian Andes, I scanned the index for landmarks on the trail ahead. Puerto Bertrand, our starting point: nothing. Lago Colonia: no. The Neff Glacier: nada. It was as if they didn’t exist.

EVERYBODY IN THE VILLAGE of Puerto Bertrand has a nickname, and one look at our boatman’s pink face and watery eyes explained his: La Chancha Ciega, “the Blind Pig.” Lago Plomo was pale green in the thin morning light as La Chancha piloted his 20-foot skiff west through spitting rain toward the Valle Soler.

Four of us—including 34-year-old Basalt, Colorado, photographer Pete McBride; Vail retailer Candice Wilhelmsen, 27; and Nate Simmons, the 35-year-old co-owner of Carbondale, Colorado–based Backbone Media—rolled in last night to find Scott and Jonathan sorting gear in front of Jonathan’s A-frame house. Tiny Puerto Bertrand looks like a displaced Irish fishing town, and in his wool sweater and beret Jonathan could pass for a fisherman—except for the long knife stuck gaucho style down his jeans. At 31, he’s got bright-blue eyes, black hair curling with its first gray wisps, and a wide-open expression.

“Welcome to the real Patagonia,” he said.

Jonathan runs the logistics from here with his wife, 31-year-old Mary Ann Mogavero, a chef, bush pilot, and horseshoes ace he met in 2001 in Bozeman, Montana. She came down to visit, went back for her two dogs, and that was that. They live here most of the year, next door to Manuel the Anarchist, a retired documentary filmmaker who’s taught his pet chicken to do backflips off his leg. Winters are long in Puerto Bertrand.

As we head out for the trail, the group swells to include Jonathan’s guides-in-training. There’s Patricio “Pato” Ormeño, a 25-year-old local with a long ponytail and fatigues; 26-year-old Juan Pablo Castillo Diaz, a Coyhaique raft guide studying tourism in Santiago; and Jose Castaño, 26, a tall Santiagan industrial designer who lived with Mary Ann’s family as a high school exchange student. The American exception is Toby Mogavero, Mary Ann’s 27-year-old brother and Jose’s partner in crime, a snowboard bro fresh from his Army tour as a Humvee gunner in Iraq. Down here, surrounded by family, he’s slowly leaving the stress of combat behind.

The boatman beaches us on a spit of land leading up to a stone house surrounded by willows. The farm belongs to rancher Ramon Sierra, who, with son-in-law Hector Soto Vargas, is providing sturdy Patagonian criollo horses, still shaggy in their winter coats, to get us up the Soler. As Ramon and Hector pull on goatskin chaps and nylon slickers, we head up-valley, following the faint trails left by huemules, Patagonia’s endangered red deer. Upriver, 9,399-foot Cerro Hades is busy making weather.

The route forms a giant C. We’ll head west along the 17-mile-long Valle Soler, using the horses to cross the Río Soler’s swollen glacial runoff. In two days we’ll reach Palomar, Jonathan’s ranch. There we’ll turn south, entering Laguna San Rafael park and leaving the ponies behind. For four days and 21 rugged miles, we’ll backpack the park, crossing the Neff Glacier and continuing past several glacial lakes. We’ll take Jonathan’s boat across the largest, Lago Colonia, exiting the national park to arrive at his second ranch, Sol de Mayo. From there it’s an eight-mile hike and ride down the Valle Colonia to the Río Baker, where we’ll meet trucks for the two-hour drive into the 6,000-person gaucho town of Cochrane.

It’s pristine, beautiful, lonely. On some trips, you can almost feel each step slide into a bootprint of the trekker who got there before you. Out here, you can believe you’re the exception. We walk with empty water bottles. No filters. No iodine. We drink straight out of every river and stream.

A few hours of wet hiking brings us to a field of RV-size boulders. Scattered among the rocks are six green Eureka A-frames, half blown over by the wind. Jonathan finds a cow femur to prop one up.

“We’ll have six of these tents on platforms,” he says, “and a separate 750-square-foot yurt or dome, with a table for 15, a wood-burning stove …” He gets more excited as he describes the rest—small stream turbines for electricity and running water; wastewater channeled downhill through a bathhouse with two composting toilets. He finishes off with a wonk’s analysis of sustainable firewood projections for the next 60 years.

This is the kind of long-range thinking that Jonathan and his Patagonia ���ϳԹ��� Expeditions partner, Ian Farmer, a 40-year-old British outdoor-education veteran who runs operations in Coyhaique, used to convince CONAF to endorse the trail. PAEX has a 15-year exclusive on guiding it, renewable indefinitely in five-year increments. Other outfitters may send clients, but they’ll hire horses, guides, and boats from PAEX, as will the five independent trekkers who head out every day. The Wyoming-based National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS) sends students up the Soler, and they’ll continue to do so.

So far, no other companies have squawked at this arrangement—Geographic Expeditions, the Sierra Club, and local outfitter Azimut360 have all arranged trips for 2006—but it’s ripe with potential for resentment. For that reason, Jonathan doesn’t like to use the word monopoly, stressing equal access and environmental stewardship instead.

“Ian and I took all our idealism and designed this concession that’s superstrict, even anticapitalist,” he says. “If we go above and beyond duty to create a situation where CONAF has no complaints, to create value and capital, why in the world would they kick us out?”

Never mind that on this trip we’re still burning our trash, including plastic. Never mind that Jonathan still needs to come up with $250,000 to build the yurts. We sit down in the empty boulder field in the middle of the wilderness, fortified with plates of Mary Ann’s meatballs and boxes of Gato Negro red wine.

Toby, more than any of us, needs this. All Toby ever wanted to do was ride his snowboard. Instead he found himself firing into the night on patrol outside one of Saddam’s minister’s palaces. Toby’s on inactive reserve, but in the unlikely event that the Army calls him up again, he doesn’t want to go back. He’s bought 50 acres on a trout stream overlooking Puerto Bertrand, and Jose’s going to design him a cabin where they can hang out and hide from the rain. Patagonia, he says, is his therapy.

“Dude,” Toby says from across the fire. “This place, for me, it’s healing. We came up here a couple of days ago and I kind of drifted off. I was dwelling on things, and you have to put a stop to that. This may sound kooky, but I’ll say it: Out here the mountains talk to you.”

THE MOUNTAINS ARE definitely talking to Jonathan. “Feel that wind—so empowering, yeah?” he’ll yell as we step onto a ridge and practically get blown off. “Power! How sick is this?” He’s obsessed with every bush and berry, stopping to rhapsodize about the coolness of a frog.

No one has gotten Patagonia religion quite like Jonathan. When he was a 12-year-old in Evergreen, Colorado, his mother, Cheryl, gave him a map of South America that she’d found in a dumpster outside the school where she taught.

“I slept with it every night,” he says, “and I told my mom, ‘I’m driving to southern Chile, and I’m going to go live there.’ And she was like, ‘Great—go and do it.'” In 1993, after a semester at Maine’s Colby College, 19-year-old Jonathan hitchhiked to Chile from New Mexico, where he’d been working construction, to meet up with two friends and explore the glaciers up the Valle Colonia, two days’ ride from anywhere. It was here that Jonathan met his mentor, a one-eyed gaucho named Everardo “Lalo” Ojeda Diaz. (He’d lost the eye as a young man when an ember flew up from a campfire; thanks to the charity of some nuns, he’d had a fine glass one installed in its place.) Lalo was 59 when the climbers made it to his Sol de Mayo ranch. He and his wife, Maria, fed the climbers, and when the rookies stumbled back a month later, emaciated and exhausted, they took them in again. In return, the boys worked on the farm, chopping wood.

A year later, Jonathan was river-guiding in Colorado when he got a letter. It was typed by a notary—Lalo can’t read or write. “My respected Jonathan,” it began, “I’ve decided to sell my ranch. It’s 840 hectares. It has 1,300 meters of wood fencing, a house that is six by five meters, a smokehouse that is four by five, and a barn that’s six by six. It can maintain, year-round, 100 cows, 60 sheep, and 50 goats. The offering price is $300,000.”

Jonathan left the next week. He took a plane to Santiago, another to Coyhaique, drove the eight hours to Cochrane, borrowed a horse, and rode up-valley. He told Lalo he didn’t have that kind of money; Lalo said he could wait. In 1997, after four years of guiding and taking classes, he moved to Puerto Bertrand and founded PAEX as a small rafting outfit. In October 2000, with the business finally taking off, he returned. That spring, as avalanches crashed down in the high mountains, the gaucho and the gringo worked out a deal: about half the asking price (still a large sum in rural Chile), and an easement for Lalo and Maria to live there until their deaths.

“I rode out of that valley so huge,” Jonathan says. “I was like, Holy shit.”

Jonathan’s no trustafarian. But when he moved to Chile, his father, Jim, a business consultant, took him aside. “I don’t know what’s going to happen,” he said, “but I want you to go down there and build your empire. Go and build it.” To buy the properties—first Sol de Mayo, then Palomar in 2003—they formed a 50-50 partnership, Leidich Family LLC.

“The empire thing was a weird concept for me,” says Jonathan. “But having my dad say that obviously impacted me. I was like, I’m just going to climb and study glaciers. I wasn’t into empires then, nor am I now. But that’s what you do: You try and squeak out your little domain.”

EMPIRE BUILDING IS NOTHING NEW in Patagonia. The name always mentioned is Doug Tompkins, founder of the clothing and equipment company The North Face. Starting in 1991, Tompkins amassed 714,000 acres of dense fjordland north of Aysén, a tract so vast that it bisected the country. Last year he donated that land, Parque Pumalin, to Chile as a national preserve, but he still can’t do anything without Chileans questioning his motives. The latest controversy is the 2004 acquisition of the 173,000-acre Estancia Valle Chacabuco by Conservacion Patagonica, a nonprofit founded by Tompkins’s wife, Kris McDivitt Tompkins, the former CEO of Patagonia Inc. Chacabuco is one of the most biodiverse tracts in the region, thick with condors, guanacos, and pumas. As a ranch, it is also the town of Cochrane’s biggest employer.

“Chileans are very nervous with so many gringos, because they don’t understand what’s happening,” says Peter Hartmann, a Chilean and the regional head of Comité Nacional Pro Defensa de la Fauna y Flora, Chile’s foremost green group. “They can’t think that they’re going to remain forever as cattle ranchers on poor land that’s not for cattle. Tourist land is also productive, but not, they think, for them. They haven’t seen that before.”

What they have seen is decades of resource exploitation. In the fifties, homesteaders burned close to seven million acres of Aysén forests, and the blackened skeletons of trees still dot pastures and fields. These days, 52 percent of Aysén, 21,900 square miles, is protected, but Santiago increasingly looks south for its energy needs. The Spanish-owned power company Endesa owns 94 percent of Aysén’s water rights. If the government’s pro-development bloc gets its way, two Aysén rivers will share the fate of Chile’s famed Bío-Bío, which Endesa dammed in 1996. In June 2004, Endesa announced plans for $2.5 billion in hydropower projects along the Baker and the Río Pascua, despite the huge cost of transporting the electricity a thousand miles to Santiago. In each of three proposed Río Baker scenarios—all contested by environmentalists and ranchers—Puerto Bertrand ends up underwater.

PAEX is fighting this, partly by creating tourism-based alternatives and partly by acquiring more land, a few acres here and there on the Baker to drive up prices in anticipation of an Endesa buyout. This can be delicate. “Gringo land buying is not in a good way,” explains Jonathan. “They’re not educating the seller on the perils of having a lot of money and no land. The guy moves to town, he buys a house, he buys his cousin a house, he loans his friend a truck, the truck gets crashed, and in two years he’s got no money and he’s hating it.”

Jonathan’s trying to do things differently. “The reason he’s done so well is that he’s ingratiated himself to the people,” says Al Read, founder of Geographic Expeditions. “He’ll go up and talk for an hour with a gaucho about things, about his ranch. That’s very unusual.”

Indeed, one day on the trail we spend an hour hanging out in a woodpile with an eccentric old rancher named Julio Romero, who’s been hoarding wool in his house for so long, waiting for the prices to rise, that he filled it up and had to move outside. So far, guys like him are all for the trail: They don’t want to see these roadless valleys flooded or mined, and they don’t mind making money doing the things they’re losing money doing now.

“Everybody sees the beautiful side of gaucho life,” says John Hauf, who first explored these valleys with NOLS in the 1980s and whose Patagonia Frontiers lodge sits on Lago Plomo. “They don’t see the hard work and sacrifice and the long, cold, lonely nights. But locals here realize that tourism is where it’s at for them. It’s not going to make them rich, but it’s going to allow them to keep their lifestyle and, if they do a good job, slowly increase it over time.”

Lalo agrees. “I’d been working, my horses burdened, for more than 30 years, and I was sick of it,” he says. “And yes, I always saw that this place could work for tourism. But for that you need money.”

“Some people say, ‘Those damn gringos—once they become owners they kick us out,'” Lalo tells me. “But Jonathan,” he winks, “he has good behavior, up until this date.”

JUST NOW JONATHAN’S BEHAVIOR is taking on a certain Brigham Young quality. He’s a zealot about this place, striding in front, the trail visible only to him. Pato comes next, Marlboro in teeth, machete in hand. Our packs are loaded, the terrain’s getting rougher, Scott’s battling a stomach flu that also nailed Jonathan and Mary Ann in Bertrand. We descend into giddy punchiness as we imagine recommending this slog to friends. In two days we’ve tramped through marshes and meadows and waited out the rain in the cabin of a gaucho named Muncho, passing a gourd of yerba mate, South America’s ubiquitous herbal tea, around the woodstove beneath the socks, underwear, and leg of lamb that hung drying over the fire. We’ve crossed a swinging bridge that Toby and Jonathan jury-rigged out of baling wire and dodged Muncho’s mangy, charging ram.

Now there’s the river. Crossing each bend of the Río Soler is a frontier proposition, Hector pacing his pony back and forth on wide gravel beaches as Jonathan calls out crisp questions in Spanish until they settle upon a place to ford. The horses are almost swimming, the larger ones breaking the current for the smaller ones. Nate’s pony goes in up to his withers.

Seventeen miles up-valley, a raging creek flows in clear to join the silty Soler, an unnamed peak filling the V between the two streams. This is Palomar. There’s a single one-room puesto, an outpost for a lone gaucho, and a meadow, a simple corral, and a ring of fruit trees. “Don’t step on the trout,” Jonathan calls as his horse splashes across.

Palomar is where the adventure heats up. Scott is already pale beneath his sunburn, and at breakfast Jonathan drops a kettle of boiling water on Jose’s foot, skinning a four-inch patch of his ankle. Anyone else would have taken a horse back out, but Jose limps on, fueled by Percocet and an impeccable mix of English and Spanish profanities.

It’s snowing the next day when we reach the Neff Glacier. The thing is massive, 200 yards thick in places, four miles wide. The near side is piled with loess, glacier scour embedded onto the ice. Beyond that, whiteness. Jonathan raises a fist—”Yeah! Power! Place!”—before offering up a lesson on the alarming shrinkage of Patagonia’s icefields, two of whose glaciers, the Neff and the Soler, he has measured as receding at 25 and 100 feet a year, respectively.

Soon we’re in a full-on whiteout, not the best weather for crossing crevasses unroped. “Here’s the deal,” Jonathan says as we strap on crampons. “If we get out there and there’s three feet of snow, we turn back. If a giant gorilla falls from the sky, we turn back.” We start walking at 10:30; halfway across, the sun comes out, shining down on a spectacular world of ice. Life becomes the crunch of crampons, blue ice, whiteout, sun, rain, more sun, snow. It takes seven hours.

The next afternoon we hit what’s been billed as “the burly talus slope,” a half-mile of boulders teetering on some ever-shifting angle of repose, the slope dropping straight into Lago Cachet Dos, its navy water crisply accented with small white icebergs. “Don’t slip,” Jonathan says helpfully, “or you’ll die.”

Exhilaration turns to fear. I watch Pete ride a slide into the lake up to his thigh, and the more rocks I dislodge, the more nervous and angry I get at Jonathan’s little vision of a “trail.” This guy’s a nut, I think; this place isn’t ready. We’re crossing glaciers unroped, skidding down talus, clawing up mountainsides? Maturely, I glare at the back of his peppy, bereted head and blink back tears.

My meltdown, naturally, is Jonathan’s favorite part. For a man who views his profession—”adventure guide”—as an oxymoron, this is the way it should be.

That night we camp on a rock outcrop with a front-row seat on the Colonia Glacier, less than a mile across Lago Cachet Dos. A 270-degree panorama of peaks surround us, lit by the rising full moon. It’s the single most stunning campsite any of us has ever seen, and the talus is forgotten.

We’re fried, of course. Even Jonathan confesses to being overwhelmed. It’s all getting very big. He has to build the yurts, stabilize a path across the talus slope, provide ropes for crossing the glacier. The huts themselves will come slowly—one in 2006, two in 2007, and so on. But chaos is business as usual down here: Patagonia doesn’t attract executives with thought-out business plans. It attracts grown-up 12-year-olds with grubby dumpster maps.

“The trail needs to be hard at first,” Jonathan says. “I don’t think that the millions of Americans who do adventure travel would necessarily want it to be as brutal as it is now, but there will be a lot of people who will come in the next six years who will be just thrilled to death.”

And until then? What about those who like their adventure soft-boiled? “So they’ll go somewhere on more developed treks,” he says. “It’s our time now.”

The next two days unfold in an unreal parade: glacier, peak, old-growth forest, glacier, lake, peak. We emerge onto Lago Colonia’s wide beach to see Hector, who’s come the long way around, waiting with the fishing boat. Jonathan’s going nuts: It’s been more than a decade since Scott first told him about this valley, and now—wow! yeah!—this. Leaning back in the bow, virgin mountains rising across the lake behind him, Pato lights a Marlboro Red and passes it down to Jonathan. They’ve done it.

An hour later we’re at Sol de Mayo. Lalo’s paradise is just that: two neat houses surrounded by apple trees and sheep. Mary Ann has walked up the Valle Colonia with Hector to meet us, and there’s bread baking in the woodstove.

Late the next afternoon, with only one day’s walk out to the Río Baker, I wake up from a nap in Lalo’s pasture. The Río Claro cuts two feet from the corral, rushing past the new wood-burning showers and composting outhouse, past the �ڴDz�ó��—the smokehouse, with its sheep leg drying—past Jonathan and Mary Ann’s cabin, once Lalo’s, past Lalo’s new house, with its new running water and faded poster: LA VERDAS ES EN LA NATURALEZA. In nature lies truth.

I wander over to the barn. Inside hang sheepskins, saddlebags, the goatskin that Hector and Lalo skinned yesterday to make chaps, a shopping bag reading I LOVE YOU. Hector and Lalo are shoeing a bay horse; Lalo’s sheepdog naps between its legs. I start thinking about what Cado Avenali told me back in Coyhaique.

“You look around the world,” Cado said, “and see what’s going on, and you realize that there isn’t anywhere else. This is the place. The others are places you go to look at. Here you can live.”

It’s easy to romanticize Patagonia. And you’d be a fool to think that, as more gringos arrive, there won’t be plenty of outsider arrogance. But so far idealism is overcoming the growing pains, and it’s nice to think that visitors can have some place in holding back a dam. As John Hauf put it, “That’s the beauty of Patagonia: It allows you to dream of a broader place where anything is possible.”

And so we dream of a great, big do-over at the bottom of the world. Scott’s talked about moving his young family here for a few years; Toby’s hiding out as long as he can from Iraq. As for me, I’m thinking of a little farm on the wide, blue Baker, just where the Río Neff flows in.

I won’t be a bad gringo, I tell myself. I won’t ruin anything. I’ll do it right.

GETTING THERE: LanChile Airlines () offers flights from Dallas through Santiago to Balmaceda, 35 miles south of Coyhaique, for $1,223. Or fly American Airlines () from Miami for $1,168. Hertz rents 4×4 Toyota HiLux double-cab trucks for $770 a week, but most outfitters arrange transport from Balmaceda down the gravel Carretera Austral.

WHEN TO GO: You’ll always experience sun, rain, cold, and wind in Patagonia, but November to April is the best time to visit Aysén.

IN THE CAPITAL: You can’t drive cattle through town anymore, but Coyhaique is still a frontier outpost with a civilized twist. El Reloj Hotel offers doubles overlooking an apple orchard for $66 a night (011-56-67-231108, htlelreloj@patagoniachile.cl). Fuel up on lamb and pisco sours at La Histórico Ricer, then dance all night at the Piel Roja disco.

OUTFITTERS: Patagonia ���ϳԹ��� Expeditions guides ten-day treks on the Aysén Glacier Trail for $2,300 per person, all-inclusive, from Balmaceda, as well as 11-day ice-to-ocean raft trips down the Río Baker and 14-day horsepacking trips over the Andes’ Pioneer Trail (011-56-67-219894, ). Peter “Cado” Avenali’s Salvaje Corazon outfitters runs two April photo safaris with Colorado-based landscape photographer Linde Waidhofer ($3,750; 011-56-67-211488, ).

LODGES: South of Coyhaique, on Lago General Carrera, Terra Luna Lodge rents lakeside doubles starting at $100 a night, as well as fly-fishing weeks and expeditions up 13,239-foot Monte San Valentin (011-56-67-431263, ). ���ϳԹ��� Puerto Bertrand on Lago Plomo, John Hauf’s Patagonia Frontiers ranch offers fly-fishing and horsepacking weeks, starting at $3,500, all-inclusive, from Balmaceda (307-332-7260, ).