John Cain Carter: Conserving the Amazon

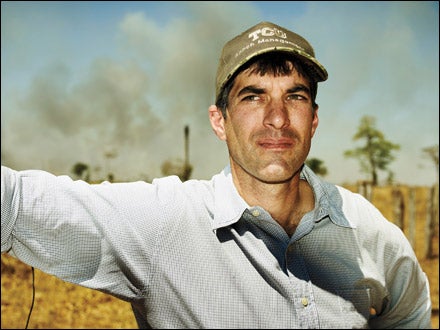

Surveying the damage from a squatter's fire

Surveying the damage from a squatter's fireJohn Cain Carter: Conserving the Amazon

Carter in the Cessna

Carter in the CessnaJohn Cain Carter: Conserving the Amazon

Inside the ranch's main house

Inside the ranch's main houseJohn Cain Carter: Conserving the Amazon

João Carlos and Marina Lutz at Fazenda Santo Antonio

João Carlos and Marina Lutz at Fazenda Santo AntonioJohn Cain Carter: Conserving the Amazon

A squatter fire on Carter's land

A squatter fire on Carter's landJohn Cain Carter: Conserving the Amazon

THE SAND UNDER the towering mango trees in front of the yellow ranch house has been raked into symmetrical lines. The cooks in the kitchen are searing filet mignon, fresh off a slaughtered 30-month-old grass-fed heifer. And the weary pantaneiros, mounted on Creole horses since 4:30 a.m., are herding their cows home. Life at Fazenda Santo Antonio do Para├şso on this lazy April evening is sauntering along at the same pace it has since 1944. That was the year the famous Brazilian general Marinho Lutz bought this wild kingdom from the first son of Colonel Henrique Paes de Barros, a man with enough sex drive to acquire 11 wives and sire 82 children.

Even with wild curassows squawking out front, the old sede, or ranch house, full of African buffalo heads, feels like a museum. For the first time since he took over the ranch from his father, in the sixties, and inherited the role of ▒Ŕ▓╣│┘░¨├ú┤ă, Jo├úo Carlos Marinho Lutz is not home to entertain his guests. He is at the doctor in S├úo Paulo. At 64, the rancher is worn out from running this massive operation and is convinced that he’ll soon drop dead of a heart attack if a white knight doesn’t surface to buy and save his exquisitely preserved $74 million, 255,000-acre property in Mato Grosso, the state bordering the southern edge of the Amazonian frontier.

“If Jo├úo Carlos were with us, he’d be drinking whiskey,” says John Cain Carter, the honorary ▒Ŕ▓╣│┘░¨├ú┤ă for the evening and the man Lutz has tapped to help broker the sale of the ranch. The two met through Carter’s Brazilian wife, Kika, 12 years ago, and their mutual love of wildlife and conservation cemented a lasting friendship.

Carter, a dark-haired, sharp-featured 42-year-old expat rancher from Texas, is wearing Wranglers and a 2006 Longhorns Rose Bowl Championship cap. Since flying down from the U.S. in his own plane in 1996, the former elite Army soldier has logged more than 500,000 nautical miles, slowly building, with his wife, a small empire of conservation-oriented enterprises, including their own 11,650-acre sustainable ranch; Brazilian ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° Travel, an ecotourism company that empowers locals; and Alian├ža da Terra, a nonprofit that offers market-based incentives to ranchers and farmers. But Carter’s most pressing project right now is to match Lutz’s high-profile property with a wealthy American buyer who will prove that ranching and conservation really can coexist.

At the moment, he’s sitting on the tile veranda, his boots in the sand, drinking a Skol beer, dipping Copenhagen, and speaking in a deep, clear twang perfected in San Antonio, where he grew up. The man who is possibly the future of Amazonian conservation could almost be mistaken for a redneck.

David Johnson, 55, tall, blond, and mustached, is on the couch with his wife, Suzie, 64, a petite former tennis instructor turned ranch hand and expert horsewoman. The couple live in Bozeman, Montana, where Johnson works as a broker for Hall & Hall, the U.S.’s largest resource-management firm dealing with high-end rural real estate. Its clients have put more private property under conservation easement than almost any other brokerage firm in the U.S. Johnson is here to size up Fazenda Santo Antonio so that he can market it to a database of 25,000 potential buyers moguls like Ted Turner, who bought most of his western holdings from Hall & Hall. Turner’s not interested, but for months Carter and Hall & Hall have been courting billionaire CEOs and iconic celebrities.

“We’ve seen less than a hundredth of this place,” says Johnson, taking a sip of beer. “But you just breathe the air here and it’s overwhelming.”

An hour ago, Carter fired up his Cessna to take us on a sunset cruise, showing us what would be lost if the ranch were sold off for more intensive agriculture.

“All that, that, that, and that would be cleared,” Carter shouted over the engine, pointing to a ridgetop still lush with native canopy forest.

The ranch balances precariously between the world’s largest wetlands the 68,000-square-mile Pantanal and the world’s largest soybean farm. While the property supports a herd of 23,000 grass-fed cattle and 7,500 acres of tilled soybean fields, 89 percent of it has been meticulously maintained in its original state, making it an island oasis for more than 420 bird species, two recently discovered insect species, and some of the most diverse wildlife in Brazil. On a Carter-led high-speed jeep safari, we found a poisonous jararaca snake, a giant anteater vacuuming out a termite mound, and a hard-charging herd of white-lipped peccaries. Beyond the lazing caimans, jabiru storks, roseate spoonbills, buff-necked ibises, jacana birds, and great egrets, Carter spotted a 400-pound tapir grazing a football field away.

“How did you see that?” I asked.

“Ah, you know,” he said. “I’m always looking out for the enemy.”

AS AN EXPAT LANDOWNER in one of the world’s last frontiers, Carter has had plenty of opportunity to make enemies. But he’s not just another gringo swooping in to save South America. Carter’s got an approach that’s very different from those of deep-pocketed predecessors like American entrepreneur Doug Tompkins. The founder of the Esprit clothing company and the North Face, and an avid conservationist, Tompkins bought up massive tracts of near-pristine wilderness in Chile and Argentina. Some locals have accused Tompkins of creating an environmental fiefdom a playground for those who can afford the luxury of not having to make a living off the land. Carter, on the other hand, has been hip-deep in cow manure for 12 years, ranching on the edge of the Amazon in northern Mato Grosso, fending off squatters trying to burn down his trees, Indians trying to steal his cows, and corrupt local officials who don’t like his foreign accent.

He represents a new breed of environmentalist: a no-bullshit, consensus-building capitalist who insists that the only way to save trees on productive land is to provide financial incentives for keeping them in the ground.

╠ř

“Americans come down here with their hippie uniforms and say, You’ve got to save the Amazon,'” Carter said our first morning in Brazil as he zipped Dave, Suzie, and me in his Toyota pickup truck toward an airplane hangar in Goi├ónia, where he and Kika, 40, and their two young daughters, Maria and Catarina, live part-time. “Well, the road to hell is paved with good intentions, and hugging a tree isn’t going to save the Amazon. You need a special-operations unit to save it.”

He may be right. Fifteen years ago, when most of Mato Grosso was still intact Amazonian transition forest, you could hardly give land away. Today, ranchers and farmers will pay up to $737 per acre for cleared land. There are still 1.6 million square miles of Brazilian Amazon forest, but it is being razed at a rate of more than 3,000 square miles per year.

Ranchers get the worst rap, for burning down trees to clear pasture. Since the sixties, worldwide beef consumption has increased by 127 percent. To keep up with demand, beef production has grown 711,000 tons per year. In 2003, Brazil surpassed the U.S. and Australia to become the world’s largest beef exporter. Countrywide production already extends over 168 million acres and, according to an executive of Frigor├şfico Minerva, one of Brazil’s largest beef exporters, there’s potential to expand to 806 million more acres. Most of that land lies in the Amazon basin.

But Carter believes that cattle ranchers can help slow down Amazonian deforestation. The trick, he argues, is to build a market that favors conservation. Four years ago he founded his own “special-ops unit,” the nonprofit Alian├ža da Terra, with this mission: to provide ranchers and farmers who agree to preserve and rehabilitate their land a network of buyers willing to pay premium prices for their products.

Before we flew off in Carter’s four-seat Cessna for a weeklong, 1,300-mile tour of his many projects in Mato Grosso, we stopped at Alian├ža headquarters. In 2004, Carter started the nonprofit with $30,000 of his own money and $270,000 in startup grants from U.S.-based Blue Moon Fund and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. Now it has 18 employees and an annual budget of $200,000, which will triple next year.

Here’s how Alian├ža works: Carter partnered with Daniel Nepstad, a former senior scientist at Massachusetts-based Woods Hole Research Center and one of the world’s foremost experts on the Amazon, and IPAM, the Amazonian Environmental Research Institute, to form a registry of Brazilian ranchers and farmers who are committed to good land stewardship. Scientists and Alian├ža employees geo-reference a property, gathering stats and information on wildlife, fire hazards, erosion, riparian zones, and deforestation. Then the landowner signs a Recuperation Management Plan, which is put into an auditing system that tracks the landowner’s compliance on a yearly basis.

“Alian├ža is a group of producers who understand what producers’ problems are,” says Ana Luisa Da Riva, a S├úo Paulo based operations officer for the International Finance Corporation (a member of the World Bank Group). “Its work is recognized by all sectors: government, the private sector, producers, and NGOs.”

Currently, Alian├ža has more than 160 properties in its system, totaling 700,000 head of cattle and nearly five million acres. Within months, ABCZ, the world’s largest cattle organization, with 16,000 members, and the Xavante Indian reservation, a 412,500-acre sprawl of degraded forest that’s home to 700 Indians, will come on board. But the crown jewel in the system is Fazenda Santo Antonio do Para├şso.

“Lutz’s property is the psychological rallying flag,” says Carter. “He’s maintained it intact for 70 years. He’s the Brazilian symbol of a good land steward.”

The big unknown for Alian├ža is whether the market rewards stewardship. The largest importers of Brazilian beef Russia, Hong Kong, Egypt, and Venezuela are hardly countries that have made sustainability a top priority. In markets where it is, like the European Union, Brazilian beef exports are highly restricted. In the U.S., fresh Brazilian beef imports aren’t allowed because of concerns over foot-and-mouth disease.

“If the European Union is demanding higher social and environmental performance, then that is probably the way the rest of the market will be going,” says Nepstad. “There are signs that even China will begin imposing environmental standards.”

But can the market change quickly enough? According to Adrian Forsyth, the vice president for programs at Blue Moon Fund, the U.S. nonprofit that gave Carter his seed money, “The combined pressure of agriculture, biofuels, and rapid climate change is going to ultimately overwhelm the region.”

Maybe that’s why Carter is in such a hurry.

A BLACK CLOUD hovers over Fazenda Esperan├ža as we descend in the Cessna through spackles of rain. We’re buzzing Carter’s own ranch so he can point out the squatter trails and burned-out plots of manioc and rice that infiltrate the forest like lice.

“Squatters are like a bad date,” he says, spitting Copenhagen into an empty water bottle. “Always out there looking for opportunity.”

A year ago, thanks to a fire started by squatters on a neighbor’s property, Carter’s ranch lit up like a gas tank, and more than 90 percent of his land burned, diminishing his 2,100-head herd of cattle to 1,400.

“Out here it’s all land wars; it’s just a state of anarchy,” Carter says as we drop onto the gravel runway. “The guy with the biggest gun wins.”

“Out here” is northern Mato Grosso, a few hundred miles north of Fazenda Santo Antonio do Para├şso, just east of the vast Xingu Indian reservation, and the region on the front lines of Amazonian deforestation.

╠ř

Carter’s ranch manager greets him with the news that his recently hired tractor driver has killed an endangered alligator. Carter’s mood goes as dark as the sky, but he can’t face off with the offender right now because one of his neighbors, a young agronomist from S├úo Paulo, has been waiting for Carter to buy some cows.

“This place has tripled in worth,” says Carter, exasperated, as we walk over to the house, a comfortable, well-manicured oasis. From the veranda you can see forever toward a charred horizon as flat and empty as the ocean. “For all the sweat equity we’ve put into it, it should have appreciated a million times.”

“When you think of ranch life, you think of the Marlboro Man,” Carter’s wife, Kika, told me when I first arrived in Goi├ónia. “But ranching is hard. This is not Texas. We do things differently in Brazil.”

╠ř

It’s been tough to get the Texas out of Carter. His grandfather Walter Wilson Carter was such a good stalker that he’d sneak up on a deer and smack it on the rump. Carter’s geologist father, Walter Jr., who taught him marksmanship and animal-tracking skills, would break up road trips across Texas to teach his son about fossils. By age six, Carter owned his first .22. By the time he was eight, he’d upgraded to a .222 rifle and a .410 shotgun. In high school, he’d wake up before dawn to check his raccoon-trap lines. And by the time Carter graduated from the University of Texas, in 1989, he had climbed every notable peak in the Rockies.

“John was a very easy child,” says his mother, Emma Roy, a real estate agent in Nashville. “He could motivate people that was his gift. And he feels very, very passionate about things.”

After college, to Emma’s horror, Carter joined the Army. At Airborne school, on his second jump, his right ankle cracked as he hit the ground. Carter left his boot on all night to reduce the swelling, ran five miles back to the airfield the next morning, then jumped out of the plane again.

His intensity eventually earned him a spot as the senior scout of an Airborne Ranger unit, the long-range surveillance detachment team assigned to the 101st Airborne Division, which pulled off dangerous missions in the Persian Gulf War from August 1990 to March 1991.

“Infantry quotes still rattle through my head on a daily basis,” says Carter. ” You gotta live hard to be hard’ and Hard times don’t last, but hard men do.’ “

In 1991 in Iraq, Carter’s six-man team was assigned a recon mission 93 miles into enemy territory. As the helicopter took off, Carter remembers, the pilot told the crew, “You are the craziest motherfuckers I’ve ever met.”

Carter earned a Bronze Star for his efforts. “The military taught me how to be a warrior, how to fight, how to turn adversity into a weapon,” he says.

After leaving the Army in 1992, Car┬şter was accepted into Texas Christian University’s Ranch Management Program, where he meta dark-haired beauty from Londrina, Brazil. Anna Francesca Carvalho Garcia Cid Kika for short was the granddaughter of Brazil’s two most famous cattle breeders, Celso Garcia Cid and Rubens de Andrade Carvalho. In 1993 Carter asked Kika to marry him.

Beginning the day after the couple’s honeymoon, Kika’s father called Carter every Sunday for two years to try to convince him to take over his ranch in northern Mato Grosso. Carter finally caved and the couple moved to Fazenda Esperan├ža in 1996.

Turns out, the Army was an ideal training ground for the Amazon. Carter has accidentally snorkeled into a nest of baby anacondas while clearing tree stumps in a swamp, survived a dog attack while hauling hunters in his Cessna (which ended with a bite on the back of his neck), and had an armed face-off with the chief of the Xavante tribe, who authorized his people to steal and kill 12 of Carter’s cows. (Since then, Carter and the chief have become friends.)

“Psychologically, all this stuff scares the shit out of you, because ain’t nobody going to pull you out,” says Car┬şter, comparing his Ranger days to life on the frontier. “But what’s important is the mission. You may be terrified, but you still do it and complete it and it makes you feel stronger almost invincible.”

Carter’s optimism scares his brother back in Texas. “He’s a lighting rod. He’s not from that culture and he never will be,” says Will Carter, 52, who lives in San Antonio and runs his own oil-and-gas-exploration company. “You stand in front of a hot stove long enough and eventually you don’t realize it’s hot.”

Shortly after Carter and Kika arrived at Fazenda Esperan├ža, a cattle thief made off with their cows. Mad as hell, Carter grabbed his rifle and hopped on his four-wheeler. Kika jumped in front of Carter to stop him. He wouldn’t budge. So Kika hopped on back.

“I remember thinking, How on earth am I going to send John’s casket back to his mother?” Kika told me. “I thought, If he’s going to die, I want to die, too. I don’t want to deal with shipping his body home in a wood box.”

By 2002, with a one-year-old daughter, Catarina, Kika had had enough of full-time frontier. The couple kept the ranch but moved to Goiânia, forcing Carter to get his fix of desperado life via Cessna commute.

The day after we arrive at Carter’s ranch, we’re scheduled to fly out after lunch, but he has to finish firing his tractor driver. Dave, Suzie, and I anxiously sit on the veranda and try to follow the heated conversation going on out back in Portuguese.

“What do you think of all this?” I ask Dave.

“I think it’s the most original operation I’ve ever seen,” he says.

“Would you ever sell a ranch in a place like this to an American?” I ask.

“The title’s solid, and the potential for appreciation is strong,” he says, looking around, “but it still has a few too many vestiges of lawlessness.”

WHAM!

“This sucks!”

Bang!

“I hate it! It’s a pain in the ass!”

Carter’s trying and failing to dodge potholes on a rain-soaked dirt runway. We’ve just dropped in on yet another Carter partnership, with the Kamayur├í tribe, which he befriended in 1996. The remote village is now a regular stop on Brazilian ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° Travel’s itinerary, the ecotourism business Carter established in 1997 with Kika and an old college buddy, Dwayne House, 42.

A swarm of naked children and a few men wearing nothing but beaded waistbands, digital wristwatches, and a red dye that makes their bodies look like they’ve been dipped in cherry Kool-Aid tentatively approach the plane.

The men and children lead us to a hut on the shores of massive Lake Ipazu, where the four of us devour the smoked peacock bass one of the men has served on a bed of manioc flatbread. The Johnsons and I don’t speak Tupi or Portuguese, and the villagers don’t speak English, so we mostly smile.

“Have you ever heard of global warming?” I ask Cotia, our thirty-something tribal guide, who has curly hair and zero body fat and is in training to become a shaman.

“The chief knows,” Cotia tells me, with Carter translating. But then he adds, “The rains started two months late and now it’s not supposed to be raining, but it is.”

“Yeah, they know what global warming is,” says Carter.

The Kamayur├í live in the southern part of the seven-million-acre Xingu reservation, home to 6,000 Indians from 15 ethnic groups. From the air, the village is a two-hour flight midway between Fazenda Santo Antonio and Fazenda Esperan├ža. By land, it takes 12 hours via river and jeep to get here from the nearest town. Ninety-five percent of the 500 or so locals have never left the village, but today chief Kotok Kamayur├í attended a festival at a neighboring village and hasn’t yet returned.

About a dozen thatched huts housing three to six families each circle the sacred men’s hut in the center of the village. On the periphery are a school, a clinic, tiled bathrooms with showers and toilets that Carter built to accommodate tourists, and an open-air hut on the lakeshore, where we string our hammocks to camp out for the night.

Carter first visited here 12 years ago. He decided to stay a month. “I wanted to figure out how to help them put value in their culture,” he says.

The tribe, best known for its beautiful jewelry, didn’t know how to count, so Carter helped them itemize their arts and crafts and came up with a price list. Then he started flying in small groups of high-dollar tourists to buy the jewelry. The program has been so successful the tourist fees ($450 per person), plus the income the Indians generate by selling their crafts, covers close to 30 percent of the tribe’s total annual operating costs that now nearby villages want a similar system.

“This is one of the best-preserved tribes in the Amazon,” says Carter. “They live in the middle of all these ranchers and farmers and haven’t been beaten into submission. Ask any villager and they’ll tell you that they don’t want to leave.”

Just when I start getting used to the idea that this may be a culture that can live without Facebook, the chief pulls up in a massive flatbed truck. Kotok is about 50, has a Beatles-style bowl cut, and is wearing flip-flops, khaki shorts, and a T-shirt. He’s smoking a cigarette and looks like a surfer.

About five minutes after Kotok arrives, he strips naked, but keeps the cigarette. Four members of a Brazilian documentary film crew came with the chief in the truck. The little kids pull up an assortment of chairs near the tailgate to watch them unload their gear. The crew is here for two weeks to tape video for a piece that will ultimately become an art installation in a museum in Bras├şlia.

When the director, ├ülvaro Andrade Garcia, finds out that the gringo in the Wranglers is John Carter, a man he’s been tracking for months because he’s a rancher sympathetic to the plight of the Indians and a passionate conservationist, he sits Carter down for an interview.

In Portuguese with the camera rolling, Carter spreads his sound bite to the world: “Ranchers aren’t devils!” he says. “The real responsibility lies on the backs of the government, a task they fail to shoulder. But along with white landowners, Indians have an important role to play in Amazonian conservation. Twenty-five percent of it is in their control. But they, like whites, need financial incentives!”

Tacum├ú, the village shaman, who’s sitting under a tree next to the film crew, slowly nods in agreement.

OUR LAST STOP in Mato Grosso is Rancho Jatob├í, Carter’s fishing camp on the River of the Dead, about a 20-minute flight east of Fazenda Esperan├ža. With guest cabins, an open-air dining area, and a deck strung with hammocks and cantilevered over the wide and lazy river, the jungle camp is set up for guests of Brazilian ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° Travel. But this is also Carter’s favorite spot in Brazil, the place he goes to get away from it all.

“The rancho is almost mystical to me,” he says. “The smells of the cerrado, the sounds of the dolphin blowing at night, the river otter screaming, the jaguar calling on the island . . . The wildness is overwhelming.”

After a morning spent casting for footlong corvina, a silvery and quick-as-lightning fish, the Johnsons, Carter, and I drive the camp car into town so Carter can negotiate buying a piece of property adjacent to Rancho Jatob├í. Then we stop off at a house with a satellite Internet connection to catch a story on Alian├ža da Terra scheduled to appear in London’s Financial Times. Carter does a quick read before we hustle back to the fishing boats to drop our lines during the witching hour.

We roar downriver, then turn into a tiny inlet to snake through dense thickets of floodplain foliage, where we find the ultimate fishing spot and crack a Skol. While Suzie’s busy catching a boatload of piranha, the conversation turns back to the sale of Fazenda Santo Antonio and the Lutz family.

“I don’t even want to think about it, I want it to happen so bad,” Carter says as he baits my hook after I’ve casted, yet again, into the trees.

Before leaving Brazil, I have a chance to meet with Jo├úo Carlos Lutz and his wife, Marina Moraes Barros, who keep an apartment in S├úo Paulo’s tranquil Jard├şn district.

Jo├úo Carlos has perfectly manicured white hair swept straight back off his forehead and a small mustache. Marina, 46, is fit and tanned and wears a gold necklace with a tiny bird charm. Jo├úo Carlos doesn’t speak much English, so Marina translates as she serves shots of strong Brazilian coffee in porcelain cups.

“The real problem is that we are naturalists, lovers of nature,” Marina says. “Our dream is to continue like that, but with the pressure of the whole world begging for soybeans, it’s difficult for us to continue.”

“It’s so rare and so special, what we have cerrado, Pantanal, high land that it needs to be preserved!” Jo├úo Carlos says. “In wars, governments don’t destroy museums, but in our country it’s difficult to find anyone concerned with conservation.”

“Conservation is in his blood,” Marina explains. “His family, his grandfather, his aunts, his uncles they were all naturalists, all lovers of nature.”

“My whole life is this country,” Jo├úo Carlos says. “I’m 64, I have a small future. I want to start other things.”

“Who would be your perfect buyer?” I ask Marina and Jo├úo Carlos, who have already had five solid offers on the ranch, all at full asking price, from encroaching soybean, rubber, and sugar conglomerates.

“First, the buyer must be a real conservationist,” Marina tells me.

“Then he would need to create a scientific foundation,” Jo├úo Carlos adds.

Their dream is turning out to be a tall order for Carter. It’s tough to dam ten million holes with only ten human fingers.

“Jo├úo Carlos was a spark of sanity in all this madness,” Carter said, addressing the monstrous task at hand while casting for corvina back at his camp. “I was neck-deep in mud here, and he was a shining light for me. If we can’t get this done, there’s something really wrong with the world.”