Something strange is happening to Carlos Villalon’s trousers. We’re trekking through a drenching rainstorm in the Chapare region of central BoliviaÔÇöa waterlogged sliver of primeval jungles and chocolate rivers that spill over their banks each winter with terrifying predictability. Eight policemen from Bolivia’s special antidrug squad, the Leopards, are leading the way through the rainforest. They’re looking for a primitive laboratory, often no more than a pit dug into the earth, lined with plastic, and covered by a thatch roof, where narcotraficantes turn coca leaf into coca paste, the first step in making cocaine. Half an hour into the hike, we notice the weird phenomenon taking place below Villalon’s waist.

Bolivia

A coca growers' mural

A coca growers' muralBolivia

Bolivian forces on the march to eradicate coca in the Chapare region

Bolivian forces on the march to eradicate coca in the Chapare regionBolivia

Packing 50-pound bags of coca leaf

Packing 50-pound bags of coca leafBolivia

Weighing the spoils near La Paz

Weighing the spoils near La PazBolivia

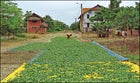

Drying coca leaves in a village in the Chapare region

Drying coca leaves in a village in the Chapare region“Holy shit!” cries Evan Abramson, a 29-year-old Long IslandÔÇôborn expat whom I’ve hired as a fixer. “Hey, Carlos, man, check out your pants!” Villalon, our 41-year-old Chilean photographer, looks down. His once-green cargo pants have turned white, and they’re brimming over with soap suds. “What the fuck?” he exclaims, running his hands over the foaming mess.

He lets loose a torrent of Spanish obscenities, and the troops cackle in amusement. It seems that during a recent power failure at his home in Bogot├í, Villalon’s laundress never put the trousers through the rinse cycle, hanging them up to dry instead, with the detergent suffusing every fiber, then stashing them back in his closet. Now the heavy rainÔÇöwhich has soaked through our ponchos, fogged our glasses, ruined our notebooks, short-circuited our cameras, and dissolved our cigarettes into wet shreds of tobacco and disgusting brown-stained scraps of paperÔÇöis performing the rinse cycle for him.

“When I get back to Bogot├í, I’m gonna fire that fucking washerwoman,” he says.

We press on through a tangle of giant ferns, spine-covered palms with roots that divide like octopus tentacles high above the ground, and wild papaya trees. Fire ants attack every exposed bit of flesh, leaving red welts. The soldiers curse but plod on, repeatedly sniffing the air like bloodhounds for the telltale chemical smell of a “maceration pit”ÔÇöwhere coca is stomped into liquefied mash and the alkaloid is separated with a mix of gasoline, lime, and sulfuric acid. On top of all the other unpleasantness, the Leopards have only one machete among them, which makes hacking through the jungle next to impossible. At one point we find ourselves caught in thick brush with no apparent way out.

Up strides Armando Azturicaga, the lean-faced, no-nonsense officer who commands this unit. He’s trained with the Green Berets at the School of the Americas, in Fort Benning, Georgia, then in Washington, D.C., with the Drug Enforcement Administration. He stares at Carlos’s frothing trousers with an air of contempt. “This is bullshit,” he says. “Let’s get moving.”

Azturicaga has been running drug interdictions in the Chapare for the past year and a half, and if he seems impatient with the way things are going, it’s understandable. For two decades, the U.S. and Bolivian governments have worked closely together on an antidrug program (this year the budget is $34 million) that combines aerial surveys, on-the-ground destruction of coca plantations, raids on labs, and arrests of cocaine smugglers. But since Evo Morales, an Aymara Indian and the charismatic leader of a coca growers’ union, became Bolivia’s president, in January 2006, the jungle has exploded with coca leaf. Morales, 48, proposed a law that would almost double legal coca growing, ostensibly to promote the leaf’s traditional use in Andean culture. At the same time, he’s permitted the raids on cocaine laboratories and drug traffickers to go on unabated.

It’s a strange paradox: The Leopards are working harder than ever, bushwhacking through the jungle seven days a week, taking down coke labs almost every day. Last year, the Leopards discovered more than 4,070 crude drug labs in the Chapare, an area roughly the size of New Jersey, as compared to 2,619 in 2005. Meanwhile, the cocaleros, the growers, are planting more and more of the leaf, with the government’s encouragement. “It just keeps growing,” Azturicaga says. Villalon, Abramson, and I look at one another, and the absurdity of the whole situation seems to hit us at the same moment. How the hell do you fight a war against coca, we wonder, when the cocalero in chief is running the country?

“COCA IS MORE THAN A PLANT, more than an herb,” Gaston Ugalde told us as we sat in his studio in La Paz’s bohemian Sopocachi neighborhood on my first evening in the 13,000-foot-high capital. Ugalde, Bolivia’s most popular artist, is a wild-looking man in his early sixties, with shoulder-length gray hair and a thick beard and mustache that suggest Jesus Christ by way of an aging Jim Morrison. “Coca leaf brings people together. It’s a means of communication,” he went on in painstaking but near-flawless English, which he’d picked up as an art student in Vancouver decades ago. “You chew, you drink, you talk. It is great for your health, your stomach, your teethÔÇöit has a lot of positive aspects to it.”

╠ř

It was one week before our soggy hike through the jungles of Chapare, and Abramson, who has lived in Bolivia for two and a half years, led me to Ugalde, the shaggy prophet of the coca ░¨▒▒╣┤ă▒˘│▄│Žż▒├│▓ď. Born and raised in La Paz, Ugalde has been billed as Bolivia’s Andy Warhol, churning out playful, pop-arty collages, sculptures, and paintings filled with references to the country’s indigenous culture. Ugalde has been a devotee of coca since he was in his twenties, and over in the corner was the reason we’d chased him down: a series of collage portraitsÔÇöAymara Indians, obscure Bolivian leftistsÔÇödone entirely with coca leaves. Early in his career he studied with William E. Carter, a U.S. anthropologist who spent several years in Bolivia in the sixties and seventies, observing the effects of coca chewing on Andean Indians, who’ve been using the leaf, a stimulant akin to a powerful energy drink, since well before the rise of the Inca empire. One study’s results showed that regular chewers ate more food than non-chewers, which contradicts the view of coca as an appetite suppressant. Ugalde made his first coca-leaf portrait in 1988, to celebrate the beneficial effects. In 2002 he displayed a series of coca portraits in a New York City gallery. Then, last year, Ugalde’s artistic passion collided auspiciously with the Bolivian zeitgeist. Shortly after his inauguration, Morales summoned Ugalde to the palace, a grandiose colonial edifice on the Plaza Murillo, in the heart of La Paz, and asked him to make the official presidential portraitÔÇöusing coca leaf. Coca portraits of Sim├│n Bol├şvar and Che Guevara followed (all hang prominently in the palace), as did posters that appear on highway signs and in other strategic locations, showing Aymara peasants and a single word: COCA.

To the U.S. government, Ugalde epitomizes everything that’s gone wrong with Bolivia since Morales came to power. The country, they say, has become intoxicated with coca. Morales and his cocalero cronies in the government (a coca farmer heads up the anti-narcotics effort) have relentlessly driven home the message that the leaf is a wholesome symbol of Bolivian identity. According to local sources in the Chapare, bands of cocaleros recently raided a U.S.-funded institute promoting alternative-crop development, sent the American scientists and researchers packing, and reopened the place as a college for traditional coca use, run by Cubans and Venezuelans. The Chapare town of Shinahota, epicenter of Bolivia’s cocaine trade in the seventies and early eighties, has reportedly been selected as the site of a factory to produce coca flour (used to make bread), set to open later this year, that locals say is being financed by Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez.

Problem is, even with the new flour business, the numbers don’t add up. According to surveys, Bolivians need roughly 30,000 acres of coca for “traditional uses,” including chewing and consumption of mate de coca (a kind of tea). That amount of coca leaf has long been legally provided by growers in the Yungas region of northern Bolivia. Yet the law that Morales proposed last year would raise the legal cultivation limit of coca in Bolivia to roughly 50,000 acres, and a 2006 United Nations survey states the total acreage as significantly higherÔÇöclose to 68,000. Some 75 percent of the coca leaf, U.S. officials estimate, is distilled into cocaine base and exported to Brazil and Argentina, as well as Europe and, in small amounts, the United States. “Bolivia is heading back to becoming a major supplier of cocaine in the international drug trade,” I was told by one American official in the Chapare. “It’s now going to be right up there with Peru and Colombia.”

Why would Morales promote a crop whose principal end product is cocaine? After all, angering the United States government may be fine if you’re Hugo Chavez, the swaggering president of oil-rich Venezuela (and Morales’s close friend in the region, which has lately seen left-leaning presidents come to power in Ecuador, Argentina, Peru, and Nicaragua). But if you’re the leader of Bolivia, the poorest country in South America, making an enemy of George Bush may not be the wisest strategy. U.S. officials speculate that Morales believes he’s merely making de jure what was a de facto situation: that farmers in the Chapare were already growing about 20,000 acres of the crop illicitly, despite decades of anti-coca policies. A top American official in the Chapare says that Morales has found himself in an impossible position: He owes his presidential victory to the support of the cocaleros, from whose ranks he rose. At the same time, Morales knows that it would be foolish to prevent the Bolivian army and police from taking out cocaine labs and smugglers. His position is that there will be no zero coca, just zero cocaine. His constituency is the growers, after all, not the narcotraficantes. A Western diplomat in La Paz describes Morales’s mind-set this way: “His whole history is that of a coca-growing leader. Now combine that fact with his need to feed his political base and the fact that he doesn’t see [coca] as particularly harmful. They tell you that ‘We’re just producing the bullets; you have got to get the gun’. But it’s not an intellectually satisfying argument.”

I ran into Gaston Ugalde the following evening at Le Com├ędie, the best French restaurant in La Paz. The artist laureate was holding court at a center table, surrounded by half a dozen beautiful young women. Around town Ugalde is known as a party animal, and his celebrity has grown since he became the official court painter. He spotted me walking in with a friend and flashed a small smile. I told him that before dawn we’d be flying down to Cochabamba, in the Andes, and from there we’d drive to the Chapare, where coca is king. He had a dreamy look in his eyes. “Buen viaje,” he said.

NEARLY 7,000 FEET BELOW COCHABAMBA, reached by a rutted switchback highway that plunges through jungled canyons, lies Villa Tunari, the biggest town in the Chapare. Villa Tunari has been billed as the epicenter of the country’s “eco-adventure-tourism industry,” offering activities ranging from river rafting to birdwatching. But it’s hard to promote ecotourism when the jungles are riddled with cocaine laboratories and the whole region has for years been the site of a bloody battle between coca growers and the U.S.-backed Bolivian antidrug forces.

A dozen or so near-empty eco-lodges littered the roadside, remnants of a tourist mecca that never fully realized its potential. Half a dozen bedraggled backpackers, both Europeans and Americans, wandered along the muddy main road or sat in ramshackle caf├ęs sipping Coke Zero, a new diet soft drink that provides an inadvertent pun on the brutal Bolivian and U.S. coca-eradication policy that ended in 2002.

╠ř

We stopped for lunch at an outdoor restaurant in the center of town. There were four of us now: Villalon, Abramson, me, and Fernando Salazar, a pudgy, affable social scientist from Cochabamba whom we hired as our translator and assistant. The place was deserted. Large, dusty jars filled with boa constrictors pickled in formaldehyde lined the counter in front, along with preserved wild-pig fetuses, lizards, and other rainforest oddities. “Charming,” said Abramson. “Just the thing you want to look at over lunch.” A young waiter shuffled over and slapped down a few grease-stained menus: The choices were wild pig, antelope, or some large river-bottom feeder grilled with clarified butter. No boa constrictor? I asked. He stared back, uncomprehending.

The grainy black-and-white television in the back of the caf├ę blared the local news. Teachers were on strike. Miners were threatening a strike. In La Paz, long lines of people waited through the night for cooking gas. The big story of the week was the hunger strike that passengers called after Bolivia’s biggest airline, Lloyd Aereo Boliviano, allegedly went belly-up, leaving hundreds stranded at the country’s airports. The camera panned across haggard families sleeping in front of abandoned check-in counters, surrounded by placards demanding intervention: COMPANERO EVO MORALES DOESN’T DEFEND US, one declared. HE IS ONLY FOR THE COCALEROS, BUT WE ARE ALSO BOLIVIANS!

About the only place in that somnolent burg where we found any activity was the soccer field, which Salazar took us to after lunch. We were looking for Rolando Pacheco, head of field operations for the Economic and Social Development Office in the Tropic of CochabambaÔÇöthe man responsible, at least before Morales came along, for locating and destroying coca plantations in the Chapare jungles. We found himÔÇöa chain-smoking tecnico, or coca eradicator, who looked to be in his early fiftiesÔÇöcheering on a bench at one end of the field, where two dozen mud-splattered young tecnicos were playing one of the most furious matches I’ve ever seen. I shook Pacheco’s hand and jokingly asked him whether the tecnicos ever played teams of narcotraficantes or cocaleros. He cracked a sad-eyed smile.

Pacheco remembers the dark days after the 1980 military coup. Under that corrupt dictatorship, cocaine base was sold openly in town markets. One of the country’s most powerful drug traffickers, Roberto Suarez, hired Klaus BarbieÔÇöformer Gestapo chief of Lyon, who’d taken refuge in Bolivia after World War IIÔÇöas his security consultant. They used soldiers and mercenaries such as Los Pajaros Negros (“the Blackbirds”) and Los Novios de la Muerte (“the Fianc├ęs of Death”) to guard plantations and eliminate would-be competitors. “The army became filthy rich,” I was told by one expert.

Then, in 1982, Bolivia flip-flopped. Massive street protests against the military resulted in the establishment of a civilian-led democratic government. The following year the U.S. helped to create UMOPAR (“Mobile Units for the Patrolling of Rural Areas”), a special police unit responsible for cocaine interdiction. In 1998, American-trained antidrug forces launched Plan Dignidad, otherwise known as “Coca Zero,” which, by 2000, brought the country’s total coca acreage down to about 36,000. The sweeps unified the coca federations in resistance, helping propel Morales to power.

In 2004, as the chief of the cocaleros‘ union, Morales forced President Carlos MesaÔÇöwho was unwilling to provoke further violence between the government and the cocalerosÔÇöto sign an agreement to allow roughly 8,000 acres for coca cultivation in the Chapare. The agreement also gave farming families in the region the right to own a cato, or a little less than half an acre, of the crop. Then, in his 2006 proposed law, Morales not only sought to up the legal acreage but to grant individual proprietors the right to divide their farms among immediate family members over age 18, each of whom could also grow a cato. After 25 years and hundreds of millions spent on eradication and alternative development, Salazar told me, “the U.S. managed to reduce the coca crop from 110,000 to 60,000 acres. In the end, the cocaleros won the fight.”

After a few minutes of watching soccer, Pacheco led us into a back room in the tecnicos‘ compound down the road from the soccer field. Times have changed, said Pacheco: The powerful local federacionesÔÇöwhich dole out land to peasant farmers, collect taxes, market coca, and build schoolsÔÇöare supposed to make sure that everybody keeps to his legal limit. The new buzz phrase in Bolivia is “social control.” But there’s no way to guarantee that the farmers and federation leaders are behaving honestly. Pacheco pulled out a recent satellite map of the Department of Cochabamba, the province that includes the Chapare. It was covered with tiny green circles, each one representing a field of coca; there must’ve been thousands of them. “There is no control,” Pacheco admitted. Earlier, Salazar had told us that Pacheco was depressed. He was watching his life’s work go to hell. The sad-sack tecnico boss had been, in his day, one of the hardest anti-cocalero ideologues in the Chapare. Pacheco keeps his cards close to his vest, however. When I asked him how he felt about the coca reforms, he shrugged and replied, “It’s not my place to get into politics.”

PACHECO WAS EAGER to take us out to see how the new policy is playing on the ground, but it wasn’t simple to arrange. We had to get written permission from myriad generals and police commanders, and it wasn’t clear who had to sign the paperwork. One morning we were summoned to a meeting with an army colonel at the base in Chimore, a ramshackle assemblage of stucco buildings and Vietnam-era U.S. attack helicopters moldering in the heat. When the colonel, friendly but ramrod straight, told us that an expected fax from a general in La Paz still hadn’t arrived, Abramson, who displayed an impulsive streak that threatened to get us into trouble, blurted out “What the fuck?!” The colonel flinched, and Salazar gave Abramson a look from hell.

Abramson had been chewing coca almost nonstop: He’d bought two pounds of leaf for about US$6 in a La Paz market just before starting our journey, and he carried the bag with him everywhere. Every 15 minutes he fished out a fistful, rolled it into a wad around a small chunk of lagia, a hashish-textured chunk of ash and banana peel that helps bring out the alkaloid-rich juices, and shoved it between his gum and his lower cheek. I’d started chewing the leaf myself to keep me going on the grueling, six-hour road trip from Cochabamba to Chapare, and I was becoming as much of an addict as Abramson. I found myself shoving ever-larger wads of the stuff into my mouth, and soon my lips had turned black and my teeth were speckled with bits of leaf.

@#95;box photo=image_2 alt=image_2_alt@#95;box

One evening in a steady drizzle, I was driving us back from another visit to the army base. The Land Cruiser’s weak headlights barely registered on the fog-shrouded highway. Eighteen-wheelers and battered buses bound for Santa Cruz and Brazil rumbled by in the opposite direction with their brights on, blinding me.

“I can’t see a goddamn thing,” I said.

“Slow down to 15 miles an hour, man, if you have to,” said Villalon. “Just get us back to Villa Tunari in one fucking piece.”

Abramson was on the phone with Salazar, who’d spent the whole day back in La Paz pleading with the vice minister of coca, an old friend, to help obtain permissions from the cops and the army. But he’d been told, “These authorizations take time.”

I slammed my hand against the steering wheel. What the fuck?

“I’m just the messenger,” Abramson said with a shrug, stuffing another wad of leaf in his mouth.

Suddenly Villalon grabbed my arm. “Jesus Christ!” he screamed. The Toyota’s headlights illuminated a pair of bicyclists on the shoulder of the highway. I swerved sharply to avoid them, missing by inches. I was shaken. I pulled over to the shoulder, breathing hard.

“I could have killed them,” I said.

“I know, man,” Villalon said. “Go easy on the leaf.”

The next morning, still waiting for permits, we decided to pay a visit to the Chapare backwater where Morales and his parents settled in the early eighties and began cultivating coca leaf after moving there from the Altiplano. The Morales family had herded llamas on the bleak, windswept plateau but, like thousands of their fellow Aymaras, found life untenable there after years of crippling drought. Anti-American feeling is especially strong in Morales’s rural stronghold, and Villa Tunari’s mayor arranged for us to bring along an escort for protection. We picked him up, a cocalero union leader named Jorge, at Villa Tunari’s town hall, a crumbling colonial-era villa on the main square. Jorge sat silently in the passenger seat as we drove deep into the jungle, working his way through a box of banana-cream wafers I’d bought for the entire group.

“Why did the gringos invade Iraq?” he asked me sharply.

“For a lot of reasons,” I said, annoyed.

“It was all about the oil, right?”

“Maybe that was part of it.” I began to rattle off a list of motivationsÔÇöWMDs, Israel, Bush’s personal vendetta, Cheney’s paranoid obsessions.

“No,” said Jorge. “It was oil.”

“If you say so,” I said.

After an hour we arrived in the village, bouncing down a cobblestone street past an unkempt soccer field lined with palms and banana plants. We parked in front of the coca market, a small cement-block building with a corrugated-metal roofÔÇöone of 16 collection points in the Chapare where cocaleros are obligated to bring their crop for transport to the state market in Cochabamba. One U.S. official I’d talked to earlier told me that these markets function as “one-stop shopping” for the cocaine traffickersÔÇömuch of what’s delivered here, he said, never ends up in the state market. The jungle heat was stultifying.

“Take off your sunglasses,” Salazar warned me.

“Why?” I asked.

“You look like a DEA agent.”

Inside the market stood the largest pile of coca leaves I’d yet seen, ten feet high and 15 feet longÔÇöa Mount Illimani of coca leaf. A shirtless cocalero stood thigh deep in the massive mound, running his hands through the leaves, many of which had stuck together in the humidity. The walls were covered with lurid murals that conjure up the brutal war between the cocaleros and antidrug forces: One showed an Aymara woman with a face straight out of Edvard Munch’s The Scream, hands plaintively outstretched, standing in front of burning coca fields and a line of black helicopters. UNITED WE CAN NEVER BE DEFEATED, proclaimed the slogan above the hellish scene. The cocalero stopped his toil when he saw us walk in.

“Who are the gringos?” the man asked Jorge, suspiciously.

“Periodistas,” he explained. The cocalero relaxed. He wandered over and stuffed a fistful of coca in his mouth. It was time for his pijcho, or coca break, a high point of the day for many cocaleros. He sat on a sack and offered me a wad. I wrapped it around a chunk of lagia and placed it between my gum and cheek. After a few minutes of mastication I felt the warm tingle as the alkaloid-rich juices entered my bloodstream.

“Te gusta?” he asked me.

“Mucho,” I said, and he and Jorge laughed heartily.

The cocalero turned serious. “During Coca Zero, the people suffered a lot here,” he told us. “The Yanquis tried to convince us to plant alternative crops, but it was all a lie. The soil was bad, and most of the crops died. Many people had to move away. For a while the cocaleros were divided over the issue. But now we’ve all turned back to coca.” He grinned.

Just the other day, he told us, Morales had come back to visit. He’d stayed for an hour or so, eating a plate of river fish and kicking a soccer ball around on the muddy field. “We used to call him ‘El Pelotero’ when he was younger,” the cocalero said. A fine athlete, Morales had parlayed his skill into a job as sports director of the local coca growers’ syndicateÔÇöthe position that helped speed his political rise.

The cocalero’s face lit up in amazement. “Nobody expected that we’d be so happy,” he said. “Nobody expected that Evo would become the president. It is like a dream.”

AFTER SIX DAYS and countless phone calls, our authorizations have come through, and the coca-lab interdiction mission with Azturicaga takes place without a hitch, though it leaves Abramson with a painful crotch rash that makes it almost impossible for him to walk. He bows out of the second mission the next day, an “eradication trip” with a joint task force of soldiers, police, and tecnicos. That evening, Salazar, Villalon, and I find ourselves in a military camp deep in the jungle, frantically rubbing deet into our arms, necks, and faces as mosquitoes begin to circle.

Captain Franz Ordo├▒ez Menacho, our escort, tosses us three U.S.-military-issue meals ready to eat. Salazar has never seen an MRE before. He rips open the thick plastic bag and examines the contents with fascination. “Cajun shrimp,” he reads aloud. “Pound cake… vanilla milk shake. Skittles.” I slip his shrimp dinner into the heating pouch, add water, and hand him back the warmed-up meal five minutes later. He shakes his head in wonder. “Los gringos,” he says with admiration.

The next morning we rise from our tents before dawn and jump aboard the first in a convoy of trucks bound for the eradication mission. The dirt road peters out before a cliff, and Ordo├▒ez, a handsome, bronze-skinned man in his mid-thirties, leads us, along with 89 soldiers and policemen in camouflage fatigues, down a narrow trail that plunges toward the river, 300 feet below. Two days of heavy rain have turned the path into a slippery mess; a single misstep would send a man tumbling to near-certain death over a vertical cliff face. Villalon, Salazar, and I inch across in terror. The troops navigate the trail with practiced ease, loping down toward the wide, brown river, the cops with M-16’s slung over their shoulders.

We wade knee-deep across streams, clamber over a field of boulders along the riverbank, trudge down muddy trails hemmed in by primeval flora. After a 90-minute hike, we arrive at a weathered wooden hut in a clearing littered with cooking pots, empty tin cans, corncobs, and soiled clothing. Just beyond it, we come to a chaco, or agricultural plot, covered with eight-foot-high plants: coca. In the old days, the police would have swarmed the field, hacked down the plants with machetes, and burned what was left; an ambush by angry and desperate cocaleros might happen on the way in or out. But now everything proceeds as decorously as a cricket match. Ordo├▒ez hands an inspection order to the ┤┌▒╗ň▒░¨▓╣│Žż▒├│▓ď representative, who was alerted about this visit three days ago. Wilmer Avendano, the slightly built 17-year-old son of the chaco’s registered owner, Paulina Avendano, presents his Bolivian identification card. Then, as the police form a cordon around the area, a team of tecnicos in khaki uniforms fans out across the field with tape measures, calling out numbers to a team leader who tabulates the acreage: “20 meters!” “33 meters!” “15 meters!”

The field measures about 1,400 square meters, and a tiny plot just off the jungle trail, also belonging to the Avendano family, brings the total size of the cato to the permitted 1,600 square meters. Then, just as we are about to leave, a soldier shouts from a nearby thicket. He’s discovered hundreds of illicit plants hidden in the jungleÔÇöa typical cocalero tactic. The soldiers whip out their machetes and begin chopping through the roots to prevent the coca from growing back. But even this vestige of Bolivia’s Coca Zero days proceeds with untroubled efficiency. Wilmer Avendano watches the operation and smiles. “We grew this as a ‘protest crop’ a few years ago,” he tells me. “But we’re working with the government now, and we’re fine with [the arrangement].”

Everything has gone smoothly. But I can’t avoid the impression that this choreographed “eradication” is all for show. Indeed, Ordo├▒ez tells me that many federations are engaging in fraudÔÇöinflating the number of their members, for instance, or simply not reporting coca fields hidden deep in the jungle. The captain shrugs. “A social experiment is going on here,” Ordo├▒ez says. “Who knows where it’s going to lead?”

Salazar thinks he’s got a pretty clear idea. Later that afternoon, relaxing poolside at Los Tucanes resort, in Villa Tunari, before we head back up to Cochabamba, he tells me that almost everybody in Bolivia expects both coca and cocaine production to soar in the coming months. “By next year Morales will probably increase the allowance from one cato to two catos per farmer,” he says. “The cocaleros are happy. The army is happy, too, because they are receiving these extra salaries from the United States.” He takes a swig from a bottle of Coke Zero and flashes a wry smile. “Working with coca,” he says, “is good business for everybody.”