It’s easy to let your imagination get the best of you in Chile, especially when you find yourselfÔÇöas I didÔÇöcamped at 14,150 feet in a corridor of volcanoes in the Norte Grande, the country’s arid northernmost region, with Bolivia and a scattering of minefields, planted in 1973 to discourage Bolivians from entering Chile, about five miles to the east; El Chupacabra, a chicken- and sheep-killing machine that’s hyped by the media as some sort of mythical beast (but is probably just a pack of wild dogs) rumored to be due west; and your guide’s Toyota pickup, with a dead battery, between you and the El Tatio geysers three miles to the north. Its wilderness is so vast and unexplored, and its history so rich, that you have to will yourself not to get swallowed up by your own insignificance.

Chile is a sliver of land that averages just 110 miles in width but occupies more than half of South America’s Pacific coastline; all told, it contains 32 national parks, 47 nature preserves, and 13 national monuments, covering a total of 38.8 million acresÔÇöabout 20 percent of the country. Add Parque Pumal├şn, American clothing magnate Doug Tompkins’s 1,042-square-mile private eco-playground in northernmost Patagonia, and it starts to seem like Chile is one giant wilderness reserve. And for foreign visitors, who have only had access to the country for the last ten years, it might as well be a mapless frontier. Tourists stayed away during the 1970s and 1980s, while the regime of General Augusto Pinochet brutally suppressed its left-wing and centrist opposition. But Pinochet was voted out of office in 1989, and the democrats who replaced him, including current president Ricardo Lagos Escobar, are promoting tourism. Now that it’s open, what you’ll need to take advantage of wild Chile is a couple weeks’ vacation time, a sizable chunk of change (expect U.S. prices), and an attitude adjustment. Since local entrepreneurs are only just beginning to tap into the adventure-travel market, the going can be rough, which means getting to your adventure will probably be an adventure in itself. (Need I remind you of the ill-timed dead truck battery?) In towns like San Pedro de Atacama, the hub for exploring the Atacama Desert, all that’s needed to set up shop as a “guide” for mountain-bike rides, volcano hikes, or geyser tours is a catchy advertisement on the side of a four-wheel-drive truck (in other words, first-aid and safety training may not be a priority). Chilean adventure means minimalism and self-reliance, so if you decide to hire a guide, he’ll likely expect you to fend for yourself. Whether you interpret such behavior as capriciousness or hard-core adventure, enduring it is a price you must occasionally pay.

I spent a few weeks ferreting out adventure in some of Chile’s wildest, most diverse regions, including the gorgeous, Alaska-scale wilderness of Torres del Paine National Park, where you can stage a hut-to-hut trek over a glacier and climb 8,000-foot-plus granite spires; northern Patagonia’s General Carrera Lake, a remote body of water in a region with mountainbiking, fly-fishing, and sea kayaking, where the concept of visitors is so new that there’s only one road, still unfinished after ten years of construction; and the volcanoes and salt bed of the Atacama Desert, arguably the most desolate part of the country.

The Atacama Desert

I went to the Atacama Desert to get a taste for what life is like on Mars. Really. I had heard that it was so high, harsh, and dryÔÇöin some areas it hasn’t rained in 15 yearsÔÇöthat NASA tested its Nomad solo space explorer there. Its 50,000 square miles are marked by desert flats, volcanoes, and Chile’s largest salt bed. I planned to test a few of the higher trails to acclimatize for the steep scree slopes of Mount Licancabur, a 19,455-foot volcano that’s long been held sacred by the region’s indigenous Atacame├▒an people. The launching point for me and my Chilean guides, Luis Lopez Choque, 26, and Andy Marangunic, 31, of Santiago-based outfitter Azimut 360, was San Pedro de Atacama, a small hippie-flavored tourist stop with rental mountain bikes propped up against 400-year-old adobe walls, located 700 miles north of Santiago. Azimut 360 operates 150 climbing, biking, horseback riding, and hiking expeditions in Chile each year, five of which are in the Atacama.

Luis, Andy, and I set out on a series of trips, crisscrossing the desert in the heat of day (temperatures remain in the high seventies/low eighties year-round) and camping in the frigid cold at night (a makeshift hot water bottle and a Gore-Tex bivy sack saved me when it was five below). Though much of the area can be explored without a guide, you’d be wise to hire one for more ambitious volcano treks. We went to Valle de la Luna, eight miles west of town, and hiked up a 300-foot ash dune to watch the sunset glow off the volcanoes in the east, and we saw pink flamingoes wading in the sulfury, crystallized sand bottoms of Laguna Chaxa, a salt lake 34 miles southwest of San Pedro. Always, Licancabur loomed, visible from practically everywhere within a 200-mile radius of San Pedro de Atacama.

By the end of the week we had logged more than 700 miles in the aforementioned Toyota, and it was clearly on its last legs. We ran out of time for LicancaburÔÇöthe ascent of which involves crossing into BoliviaÔÇöbut it almost didn’t matter.

Northern Patagonia

Terra Luna Lodge, which sits on a grassy hill on the southwestern shore of General Carrera Lake, at 1,955 feet the deepest lake in South America, is the first adventure lodge to lure hikers, climbers, kayakers, and mountain bikers to this remote part of northern Patagonia. Fly fishermen and some intrepid kayakers have ventured here in the past to fish and paddle the turquoise water of R├şo Baker, 15 miles southwest of Terra Luna, but precious few have made the trip down to explore the glaciers, peaks, and ice fields of 6,723-square-mile Laguna San Rafael National Park, the mountainous playground beyond the western shoreline of General Carrera Lake. Maybe that’s because it takes a while to get there; plan on a three-hour flight from Santiago to Balmaceda and then a six-hour drive to the lake.

Paula Vera, a Chilean from Santiago in her thirties, and her husband, Philippe Reuter, a 33-year-old Frenchman with arms like pipe wrenches who holds the Guinness world record for climbing up and skiing down the world’s ten highest volcanoes, own Terra Luna and Azimut 360. In November 2000, they finished construction on a plush, red-roofed pine lodge with room for 20 guests and a restaurant overlooking the lake and Mount San Valent├şn beyondÔÇöin addition to a guesthouse with four apartments. They envision the lodge as a base for hard-core expeditioners to tackle rarely explored nearby peaks, such as San Valent├şn, Patagonia’s highest at 13,310 feet.

As in other parts of Chile, Terra Luna’s sports equipment is less than state-of-the-art, and well-defined trails are scarce. Nevertheless, you can venture out on one of a litany of guided multiday expeditions, like horseback riding in the nearby San Lorenzo mountain range, rafting the Class III R├şo Baker, climbing Mount San Valent├şn, or even boating to marble caves on an island in General Carrera Lake. Philippe, Paula, and another Chilean guide lead the trips. I opted to venture out alone, and hiked through a lenga and coihue forest to the top of a nameless peak littered with seashell fossils and pedaled a mountain bike 15 miles from the headwaters of R├şo Baker back to Terra Luna on a stretch of the old gravel Carretera Austral that was so windy and lonesome I alternately sang and swore at the top of my lungs just for the sheer pleasure and terror of knowing that nobody was going to hear me.

Torres del Paine National Park

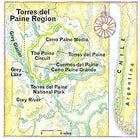

Chile’s most popular national park, Torres del Paine draws 60,000 visitors per yearÔÇöroughly 9.5 million fewer than Great Smoky Mountains National Park, the most-visited in the United States. Torres del Paine occupies a section of Patagonian steppe that stretches north for 70 miles from the small inland seaport of Puerto Natales. Most of those who venture down the 1,200 miles from Santiago trek the 60-mile Paine Circuit, a rugged, circular route around the Paine MassifÔÇöthe ultimate outdoor rock gym, comprising four solid-granite spiresÔÇöthe 9,184-foot Torres del Paine, the 8,528-foot Cuernos del Paine, the 8,036-foot Cerro Paine Medio, and the tallest peak, 10,004-foot Cerro Paine Grande. But I arrived during Chile’s late fall, and the climbing season was over. Luckily, glacier season, when you can ice-climb and trek on the park’s Southern Ice Field, never ends.

On the ride into the park from Puerto Natales with my guide, 34-year-old Chilean Sergio Echeverr├şa, the only outfitter with a permit to lead trips on the Southern Ice Field, and his 22-year-old girlfriend, Carla, my entire view was obscured by fog, save occasional glimpses of ├▒and├║s (spotted, ostrichlike birds) and guanacos (relatives of the llama) racing between the turquoise lakes to avoid their ferocious and stealthy predator, the puma. Pretty soon the clouds lifted, and whammo: There in front of me were the Torres, soaring like a giant thumbless hand into the clouds. We made our way to the base of the Torres and to Hoster├şa las Torres, a Yugoslavian-owned hotel that’s one of a handful of lodges in the park.

On our first afternoon, Sergio, Carla, and I embarked on a sunset hike up toward the spires, watching Andean condors play in the thermals as the sun sank between the towers. We turned around and navigated the four miles back to the hotel by moonlight.

The next day we drove 16 miles to Pehoe Lake, took a ferry across it, and then hiked six miles to the southern tip of the Southern Ice Field. Climbing on its premier Grey Glacier, which is receding from the northern end of Grey Lake at a rate of 56 feet per year, is like dropping through the rabbit hole to Wonderland. Slap on your crampons, grab an ice ax, and start waddling across it like a duck, and you’ll soon be gaping into a crevasse that twists like a diabolical version of a children’s slide into an underground river.

Once we hiked down to another chorus of icebergs clinking and calving against the shore of Grey Lake, we retired to Refugio Grey, a toasty nearby hut with beds, a woodstove, and a caretaker who serves as chef. We shared the hut with a British biker, a German couple, a solo Frenchwoman, two Swiss students, and two Australians, sitting around the stove drinking Chilean cabernet sauvignon from a cardboard carton and reading the cabin’s only piece of literature, the 1999 guest book, out loud. One entry read, “It’s not every day that you can go swimming with icebergs, but I did and it was fabulous.” Another read, “Chile Rocks!” I couldn’t have agreed more.

Access and Resources

Chile by the Numbers

Lowest Point: Pacific Coast, 0 feet

Highest Point: Ojos del Saldao, 22,609 feet

Average number of days it rains in the Atacama Desert per year: 1

Height of the Atacama Desert’s Et Tatio, the world’s highest geyser: 14,173 feet

Number of Chilean peaks over 19,000 feet: 15

Number of active volanoes: 47

Shortest point between a ski mountain and a beach: 99 miles

THE SEASON: November through March, summer in the Southern Hemisphere, is prime time in Patagonia, including Torres del Paine and General Carrera Lake; the Atacama Desert is temperate year-round.

GETTING THERE:

Chile is on eastern standard time, so if you fly from New York or Miami you won’t suffer a whit of jet lag. LanChile (800-735-5526; http://www.lanchile.com), the national airline, offers flights from Miami, New York, and Los Angeles starting at $915 round-trip.

GETTING AROUND: Renting cars and flying are usually the most efficient and cost-effective options. To get to Torres del Paine, LanChile offers flights to Punta Arenas, a 150-mile drive from the park, starting at $655 round-trip. For the Atacama Desert, two-hour-long flights from Santiago to Calama start at around $460 round-trip. And to get to Terra Luna, Santiago-to-Balmaceda fares start at $460 round-trip. (Bonus: free Chilean cabernet sauvignon in flight.) When you land in Punta Arenas and Calama, you’ll want to rent a four-wheel-drive vehicle. In Punta Arenas, call Hertz ($140 per day; 011-56-61-248742); in Calama, call Budget (56-55-341-076; $117 per day). In Balmaceda, arrange for transportation with Terra Luna Lodge.

OUTFITTERS: Sergio Echeverr├şa, a safety-conscious former NOLS instructor and owner of Big Foot Expeditions (56-61-414611; explore@bigfootpatagonia.com) in Puerto Natales, offers climbing, camping, and sea-kayaking trips in Torres del Paine and beyond for $55 to $150 per day. Outfitter Azimut 360 (56-67-431-263), which juggles more than 150 cycling, climbing, hiking, and trekking trips in Chile per year, prefers guests who are knowledgeable, experienced, and self-sufficient. Prices vary depending on the itinerary.

LODGING: In Torres del Paine National Park, the Hoster├şa las Torres (doubles, $89 per night including breakfast; 56-61-246054) offers basic rooms with hot showers. A shared room in Refugio Grey (56-61-412-592), the rustic hut at the base of Grey Glacier, costs $12 per night. In San Pedro de Atacama, Hoster├şa la Casa de Don Tom├ís (doubles, $68 per night; 56-55-851055; http://www.rdc.cl/dontomas) has a private outdoor patio and is within walking distance of everything in town. En route to the Atacama Desert, the Hotel el Mirador in Calama (doubles, $60; 56-55-340329) has spotless, cheerful yellow rooms and an enclosed courtyard. At northern Patagonia’s Terra Luna (56-67-431-263; t-luna@netline.cl), prices range from $60 to $150 per night, breakfast included.