Finally, he’s found: More than a year after millionaire adventurer Steve Fossett disappeared somewhere over Nevada, Madero County Sheriff John Anderson announced that searchers had discovered the wreckage of his single-engine Bellanca 10,000 feet up a mountainside near Mammoth Lakes, California. Soon after, the National Transportation Safety Board discovered remains at the scene.

So ends the most extensive search-and-rescue effort in American history. Two months before local hikers Tom Cage and Preston Morrow and weathered wad of $100 bills, correspondent JON BILLMAN tagged along on what was perhaps the most aggressive, and certainly the fittest, search effort to date-that of a group of Lycra-clad Canadian adventure racers out to test a new high-speed, low-heart-rate search and rescue approach called ���ϳԹ��� Science. Billman’s storyoriginally slated for our December issueis an exclusive look inside the aviation mystery that obsessed the nation, set in the rugged stretch of the Sierra Nevada where Fossett’s high-flying career ran aground. -THE EDITORS

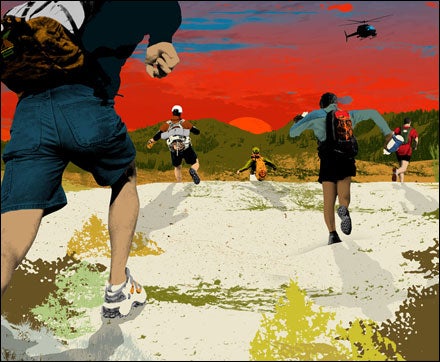

THE MEMBERS OF Team ���ϳԹ��� Science are playing air guitar and singing Iron Maiden’s “Run to the Hills” as they form a phalanx, keeping within shouting distance of each other while fanning out into the Sierra Nevada scrub. Half a dozen of North America’s top adventure racers, strapped with heart-rate monitors and slathered with BodyGlide, synchronize their compass watches and set out at high speed across ridges, down canyons, and over bare mineral earth, all while keeping critical spacing and overlapping visuals to achieve a probability of detection (POD) of at least 70 percent.

They cover the ground like grasshoppers. “Simon, there’s something shiny at two o’clock to your left, a hundred meters up,”says Paul “Turbocock” Trebilcock, 42. Simon Donato, 32, clad in a multipocketed racing vest and camo surf trunks, is the team leader and founder of the Canadian ���ϳԹ��� Racing Association. He sprints over to what turns out to be a white PVC mining-claim post. Not what he was hoping for.

What we’re looking for, Donato told us at base camp the hot July night we arrived, is probably the size of two crumpled shopping carts: a hunk of steel frame, maybe an engine block, and possibly some human remains. Donato has let me tag along with the team of six elite athletes-along with a documentary filmmaker, two base-camp coordinators, and a paramedic-that he’s gathered for a grueling week of scrambling, searching, and extreme jogging through the area surrounding Bridgeport, California, near the Nevada state line. They’ll comb these mountains at 60 percent of maximum exertion for 11 hours a day, pushing their heart rates and their luck in a hunt for a clue, any clue, to the biggest mystery in American aviation since skyjacker D.B. Cooper stepped out of a 727 over Washington State in 1971: the whereabouts of lost adventurer Steve Fossett, last seen somewhere over Nevada on September 3, 2007.

It’s scavenger hunting on a grand scale, as exhausting as any adventure race-or, according to these guys, even more exhausting.

“When you’re racing, you’re not looking,” says Eco-Challenge veteran Jim Mandelli, 47, old-school in Frank Shorter-style running shorts and low gaiters, as we scurry through the junipers. “We’re not just playing and training in the mountains. We’re looking.”

Team ���ϳԹ��� Science, trackable via their Spot GPS transmitters, is playing on the ultimate course, the roughest corners of the 20,000-square-mile grid outlined when Fossett first went down. Twenty percent of that original search terrain, Donato figures, is ideal adventure-racer habitat-forbidding ground where the wreckage could be hidden under a juniper canopy or some cliffy bit of geological chicanery-and he’s zeroed in on a rough circle, with a 62-mile radius, about 130 miles south of Reno. By Donato’s own calculations, the odds of finding the millionaire or his airplane are south of 1 percent. But for these optimistic athletes, the wreckage has become the ultimate geocache, a corporeal poker run with Steve Fossett as the prize.

IT WAS A CLEAR Labor Day morning when Steve Fossett told his pal Barron Hilton-whose million-acre Flying M Ranch, near Hawthorne, Nevada, he was visiting-that he was going for a spin. He took off at just before 9 a.m. in Hilton’s Bellanca Super Decathlon, an athletic high-wing designed more for aerobatics than any long-distance flying. The plan was to be back for lunch. A soybean tycoon from Chicago, Fossett could take care of himself; the man was the first to pilot both a hot-air balloon and a jet around the world; he’d swum the English Channel, mushed the Iditarod, and finished the Ironman Triathlon. But when he didn’t come back by nightfall, Hilton and Fossett’s wife, Peggy, launched what would become the largest and most expensive search-and-rescue operation in American history, one that would ultimately eat up $1.6 million in public and $1.2 million in private funds.

For more than a month, the search dragged on. They went big: Civil Air Patrollers blanketed the desert and subalpine sky. Walker Lake, the only big blue spot anywhere near the ranch, was seined with high-tech electronics. Expensive high-resolution photographs were fed into computers looking for anomalies. Meanwhile, amateur geeks from Switzerland and New Zealand looked for Fossett’s plane on their coffee breaks, via Google Earth. But on February 15, 2008, after the ATVs and the satellites and the dogs and the geeks turned up nothing, the 63-year-old adventurer was declared dead.

The mystery, however, was in full swing. Conspiracy theories were fermenting: Fossett had faked his disappearance; his financial ship was taking a nosedive. Fossett was only very recently “checked out” on that particular aircraft, not an easy one to fly. There’s debate over whether or not the plane was topped off with fuel. The Flying M staff pilot was the only one who saw him take off, then-maybe-a cowboy saw him south of the runway. But where was he going? And why didn’t the emergency transmitter go off?

Into this cloud bounded Simon Donato in a pair of Merrell trail runners. His plan: to use hyperfit dudes on the ground, where technology turned up nil. A stratigrapher by day, making his living mapping layers in the earth for oil exploration, Donato is also a veteran adventure racer, his résumé stuffed with sufferfests from Eco Challenge Fiji to Raid the North Extreme, Newfoundland. His idea, dubbed ���ϳԹ��� Science, is that with their superior fitness and endurance, adventure racers are ideally suited to canvass vast and rough country that turns back 4x4s and ATVs-and in a tenth of the time it takes classic foot searchers. “I had an epiphany several years ago while conducting my geology Ph.D. field work in Oman,” Donato says. “I realized that doing things ‘the easy way’-i.e., driving instead of walking-sometimes meant that crucial details were overlooked. Obviously, the high-tech method to find Fossett has failed, so it only makes sense to put the fastest and fittest people I could find on the ground to search the most difficult areas.”

The Fossett search is a test run. Donato has plans to use ���ϳԹ��� Science to look (at high speed) for dinosaur bones in Alberta next summer and to search (at peak fitness)for lost Inca cities in Peru. He explains this all on adventurescience.ca, which looks not unlike a movie trailer-“The adventure begins July 14…”-and reads like a thriller:”They will pack lightly, move quickly, and suffer extremes. They will explore the unexplored.”

Donato, however, wasn’t alone in thinking that it might take an adventurer to find an adventurer. Robert Hyman, a Washington, D.C., alpinist and Explorers Club fellow (Hyman and Donato are both members, as was Fossett) was planning a search trip for August-a self-funded undertaking with ATVs that would also test “search-planning visibility software”for NASA. Hyman, a 49-year-old private investor, told me he believed that the wreckage was in “the vertical zone,” maybe hidden under a cliff or slammed into a rock cleft, and that he’d recruited several elite climbers, Wyoming-based Exum Guides Michael Ruth, Wes Bunch, and Calvin Hebert. Unlike Team ���ϳԹ��� Science, Hyman had the blessing of Fossett’s family.

The expeditions, however, were cooperating, and both had the seriousness of purpose, Hyman emphasized, of locating a presumed dead colleague. That’s not to say there wasn’t a little polite trash talk. “I checked out Donato’s Web site. It sure seems like he’s using the Fossett name to promote himself,” Hyman emailed me. “But I hope they find the crash site.”

So did I. I have to admit, though, I arrived in the desert a skeptic. If millions of dollars and an arsenal of Space Age technology couldn’t find a multimillionaire in an airplane, how were a bunch of Canadian marathoners with Band-Aids on their Lycra-chafed nipples going to pull it off?

FOSSETT HIMSELF WOULD probably have found it pretty cool that he and the Bellanca could still disappear somewhere in the Lower 48, that it was still wild enough down there. He also would likely have approved of Donato’s sporting search methods. “My competitive nature,” Fossett wrote in his 2006 autobiography, Chasing the Wind, “combined with the methodical use of statistical probabilities, added up to a winning formula.”

Donato’s biggest challenge was selecting a search area. He spent the winter studying maps and talking with pilots, aeronautical engineers, and search-and-rescue experts, as well as “Clairvoyant Kim” Dennis, a Calgary medium who’d supposedly reached out to Fossett in the spirit world and discovered he’d crash-landed in a marsh.

Ultimately, he decided that Fossett was most likely “on the edge of the Sierra Nevada, where difficult winds, steep drainages, and generally more dense vegetation could conceal the wreckage.” In May, Donato hired a pilot to fly him over this area, concluding that, because Fossett had many hours of flying gliders in the area, famous for massive thermals, and had, Donato heard, told people at the Flying M that he planned to fly Highway 395, the aviator may have been vectoring toward Yosemite-in the vicinity of Amelia Earhart Peak. Torn between an area to the north, around Bridgeport, and a stretch of wild terrain to the south, closer to the national park (and near where the wreckage would ultimately be found). Donato chose north.

This is where we find ourselves during the first team briefing, sitting under an easy-up tent in base camp-the Bridgeport RV Park-under a waxing moon. Donato has assembled an A-team of jocks. In addition to “Turbocock” Trebilcock, a former Canadian ultramarathon national champion also known as “Carpenter Paul” for his role on the Canuck version of TV show Trading Spaces, there’s Jim Mandelli, a Lions Bay, B.C., structural architect and veteran of the Raid Galoise; Derek Caveney, a 31-year-old Toyota scientist and expert mountain biker; Greg Marshall, 30, a high-school teacher who went to grade school with Donato; and Gary Hudson, 26, a massage therapist and world-class duathlete. Supporting the team is the lone American, 41-year-old Greg Francek, 41, a former Primal Quest race director and Amador County, California, search-and-rescue deputy who’s been confined to field support after a fall from his roof; base camp manager Keith Szlater, 54, a Calgary-based search-and-rescue expert; and Tyler LeBlanc, a 24-year-old Whitehorse paramedic toting a kit full of drugs and bandages, just in case.

“We’re looking for plane wreckage,” Donato says as the team shovels in spaghetti, carbo-loading for the day ahead. “We’re not looking for a body.” Everyone nods. And no photos when we find him, he continues. “It’s about respect.”

Donato sketches out the week ahead. Every morning at the RV park, we’ll wake at dawn for breakfast-during which Donato will blast “Run to the Hills” from his laptop while we eat oatmeal-and, at 7:00 sharp, Team Alpha will load into Mobile One (Jim Mandelli’s Xterra) and motor out to good Steve Fossett territory. There, we’ll fan out like so many bright boomerangs, checking our 20s on family-band radios, and trying our damnedest to find an airplane. Through it all, the team would be recording their heart rates for a study for Donato’s Ontario alma mater, McMaster University, on the physiological effects and caloric requirements of running around looking for a dead guy in a plane.

What nobody brings up is the possibility of not finding Fossett. These athletes are used to winning, and they’ve visualized success, practiced finding Fossett in their minds. As a leader, Donato exudes not hope but rather probability and relativity, and when it comes down to it, he can play himself in the movie. He put himself through McMaster in part by modeling for Harlequin romance covers-naughty-dancing with comely PhotoShop partners on Beyond Daring and holding a baby and smiling on An Honorable Texan, as if he just found the little guy in the woods and, hey, no prob, it’s what I do.

Still, the pressure is on Donato. Everyone’s paid their own way here and given up vacation time for the cause. Hopes are high-not just for the glory of solving the Fossett mystery or for the looming documentary being filmed by Donato’s fraternity brother Lindsay Robles but for the promise of ���ϳԹ��� Science itself. ���ϳԹ��� racing, poised to go big when Survivor producer Mark Burnett began airing EcoChallenge races on the Discovery Channel in the nineties, has faded from the primal-time radar, written off as a hyperactive corporate team-building exercise that wasn’t very television friendly. But what if that exhilaration, that sense of mission, could be applied for good? Even if Team ���ϳԹ��� Science didn’t find a stick of evidence, they might still spawn something of a new extreme sport.

MIDMORNING DAY ONE and we already have a break. Base-camp manager Keith Szlater, with a Calgary cowboy mustache that fits right in here on the Nevada line, is frantic on the radio-“We’ve got a very interesting development here”-and he’s leaving his post!

Soon a white Jeep with California plates growls to the day’s search site, near the ghost town of Chemung Mine, where the team is having a lunch of trail mix and V8. Keith is riding shotgun with a local named Tom-no last name, no photographs, please-who enjoys a mid-morning Miller High Life while he tells us he was up here cutting firewood last Labor Day, the day Fossett disappeared. He and his buddy were taking a cigarette break with the saws off and heard a small plane sputtering.

This is called “local knowledge,” and there seems to be no shortage of it. But the guy appears legit. “I guarantee nobody searched in there on the ground,” he says, pointing southward toward a canyon especially thick with piñon and juniper. “It’s a real tough area to get into. You could land a 727 in there and no one would ever see it.” Tom said he told the Mono County Sheriff Department, but they didn’t seem too interested.

But the tip is a bust. By the end of two hot, grueling days, all we’ve found is a windscreen from a snowmobile, many old beer cans, an arrowhead, an antique Canadian-whisky bottle, and a boot. We’re sunburned, blistered, and scratched from sagebrush and alder sharp as punji sticks.

The next day, at 10,000 feet on the eastern shoulder of snowcapped Mt. Patterson, Simon finds a battered aluminum door. He carries it out of the trees as if it were a Roman shield. The door is full of bullet holes.

“If that’s his door,”someone jokes, “it’s proof that Steve Fossett was shot down.” The door appears to me to be from a snowcat-there’s a rusty hinge and the handle isn’t recessed for aerodynamics. At best it’s a military antique. But the news that Team ���ϳԹ��� Science has found an airplane door makes the newswires nonetheless, and it gives us hope. The door is a symbol, a reminder that Fossett really could be out here.

In my fatigue I find myself getting caught up in the spirit of the search. My back hurts from sleeping in the dirt, but I can feel success close at hand. At dawn, midweek, I spring out of my tent, gobble down my oatmeal, lace up my trail runners, and do a little stretching while playing hackysack with the guys. My skepticism clears away and I join in with the daily Iron Maiden air-guitar jam. I’m becoming a Team ���ϳԹ��� Science homer: I want to find Fossett. Closure for the family is great and all that, but goddammit, I want to win! Where the hell is that airplane?

BY FRIDAY EVENING, Team ���ϳԹ��� Science has combed 62 miles, climbed and descended thousands of feet, and consumed a case of Costco canned salmon. We haven’t spoken with a woman since Monday, when a Reno news anchor drove up to interview Donato. Three nights ago, morale was so low he had to rally us to Travertine Hot Springs, south of base camp, to soak sore bones and check out naked hippie chicks.

On Saturday morning, our last day, the search takes on the bittersweet feel of winding down-bitter because we haven’t found Fossett and sweet because tonight we’ll be in Reno, which rhymes with casino. Carpenter Paul is wearing bulbous leopard-print sunglasses. “I’m feeling a little depression that we didn’t find something,”he says. “We’re all fucking athletes here, we like to win, right?”

We break camp and head southeast in the Xterra, taking the long route to Reno, 130 miles north, to check out more canyons. A couple nights ago, Donato spent hours on the phone with an aviation expert in Hawaii who said he’d studied some radar tracks he thought might be Fossett’s near Cottonwood Canyon, and Donato is afflicted with second-guessing. Cottonwood is also within the area that Robert Hyman’s team has target=ed, and, after our own brutal week, Donato thinks we can give it a quick recon for their effort.

Cottonwood Canyon is on a military depot, and we have to hop a big yellow government entrance gate to gain access. Our watches tell us it’s 104 degrees, the kind of hot that turns the water in your hydration bladder to warm spit. There are shiny things on the canyon walls and Simon, like Ahab, is glassing them. He takes off up the scree to verify that a shiny piece of juniper is just a piece of wood.

Some of the guys are dubious: This area has been searched extensively from the air. “The logic is gone,” says Mandelli, a voice of aged wisdom throughout the week. “We all have hope, but this week’s done. The wheels are falling off.”

We head upcanyon anyway. “I’ve been following Simon around on his bad ideas for 27 years,”his buddy Greg Marshall says. “I’m not gonna stop now.”

The team hikes a mile or so higher, and if this were a western, there’d be forlorn whistles and rattlesnake sounds. Donato’s stride says he’d scramble all the way to Reno if need be. Then finally he stops, toes gravel with his shoe, and does a 180. There is a moment of silence. A jet shoots through the distance.

“All right. That’s it,”Donato says. “Let’s go to Reno.”

It’s hard to admit defeat, to call it without victory. Now, standing out in the desert with no sign of an aviator, there’s only one thing for an elite athlete to do. Race!It’s a simple cross-country start for what the GPS tells us will be a four-mile footrace back to the vehicles, where Szlater is running the air conditioning and drinking Sprite. Not exactly the Raid Gauloises, but the winner gets his own bed in Reno and won’t have to spoon a teammate, like Ishmael and Queeqeg at the Spouter Inn.

Derek Caveney starts us: “On your marks. Get set. Go!” Turbocock takes a quick lead. Gary Hudson holds steady, then starts to build momentum. But then, a mile and a half down, Donato pulls up sharply. I slow and ask if he’s OK.

“I’m good,” he says and ducks into the alders alongside Cottonwood Creek. Captain Donato is off-course! He’s forfeiting the race! “I just want to take a quick look in here,”he hollers over his shoulder, then disappears into the thicket.

JOGGERS ARE ALWAYS finding a body-just pick up the morning paper. Fast forward two months and this time it was a hiker: I got the news from Simon that Preston Morrow, the manager of Kittredge Sports in Mammoth Lakes, California, had found Fossett’s aviation ID cards and a grand in cash in pine needles off a goat path seven miles west of the Mammoth Mountain ski resort. This was 60 miles from where we’d been searching on the Nevada border; at least Donato had chipped the search area down from 20,000 square miles to within 60 miles of the bull’s-eye. His instincts were right. He was eating an apple at his desk, taking a break from finding oil and looking at the probable crash site on Google Earth. “This is five kilometers from where I’d wanted to go next, if we’d had more time and money.”

A flurry of e-mails landed in my box from all the Team ���ϳԹ��� Science members. They were chomping at the bit to be out there with crews from the Madero County Sheriff’s Department, above 9,000 feet, searching for the wreckage in terrain not accessible by anything with wheels. Greg Francek, the Amador County deputy, was headed up to the command center to assist in the search and recovery operation. There was no schadenfreude, rather something much closer to sportsmanship.

“I’m just so glad that we can put any conspiracy to rest,” Robert Hyman told me Thursday, the day searchers found the fuselage and then, late in the day, pieces of human remains they’ll use to match DNA with Fossett’s. The mass of the wreckage was, true to high-speed impact form, the size of a couple of crumpled shopping carts. “I’m most glad they found Steve. If we can help search-and-rescue methodology in the future, great.”

That’s still Donato’s hope. The hunt for Fossett is over. But there are still dinosaur bones to be found in Alberta and melting ice fields in Greenland to explore. Team ���ϳԹ��� Science is just getting started.