FIFTY MILES FROM JUST ABOUT ANYWHERE, Richard Ingebretsen and his colleague Jeri Ledbetter stand on a rented ski boat, looking at one of Glen CanyonÕs most famous landmarks: the Cathedral in the Desert. Rising from the receding waters of Lake Powell—a 186-mile-long Colorado River reservoir that sprawls across the Utah-Arizona state line—are the sloping walls of the 150-foot natural amphitheater, still half dunked in piney green water and looking like a sandstone bathtub with a chalky scum ring.

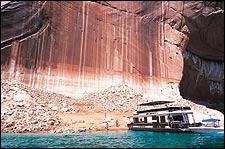

Half empty or half full? Houseboaters examine exposed Lake Powell shoreline

Half empty or half full? Houseboaters examine exposed Lake Powell shoreline

The Cathedral is temporarily visible this year because the worst drought to hit the Four Corners since 1977 has been lowering Lake Powell an astonishing three inches per day. Hydrologists estimate that by the end of this month, the 560-foot-deep lake will have dropped by 80 feet, exposing more of the Cathedral and dozens of other waterlogged splendors for the first time since the Carter administration.

All of which has Ingebretsen thinking revolutionary thoughts. An avuncular 46-year-old Salt Lake City physician who in 1996 founded the Glen Canyon Institute—a nonprofit dedicated to draining Lake Powell—he’s seizing the moment to push the idea of keeping the lake half full. The plan sounds far-fetched, but it’s gaining political momentum and may have a chance of success, depending on the outcome of this month’s midterm congressional elections. For Ingebretsen and other activists, though, lowering the lake is just a baby step toward the real goal: decommissioning Glen Canyon Dam and draining Lake Powell entirely. “In my view, trends mean everything,” he says. “And the trend now is dam decommissioning. The trend now is to discuss it.”

When the muddy Colorado River started backing up behind the floodgates of the dam in 1963, it marked the Faustian payday of a deal made by the fledgling environmental movement. The dam was built mainly as a holding tank to satisfy the mandates of the 1922 Colorado River Compact, which obliges upstream states to deliver a specific amount of water downstream each year.

In exchange for keeping dams out of the Grand Canyon and Dinosaur National Monument, environmentalists, led by the Sierra Club’s David Brower, signed off on the 710-foot concrete plug in Glen Canyon, creating an upstream powerboat oasis. In advance of the deluge, Brower and others began visiting and documenting Glen Canyon’s archaeological sites and side canyons, and realized their mistake. “Glen Canyon died,” Brower wrote in 1963, “and I was partly responsible for its needless death.”

Since then, Lake Powell has become “the symbol of all that has been lost,” ccording to Carl Pope, 47, executive director of the Sierra Club. But it wasn’t until 1996 that a serious anti-dam push got going, when Brower convinced the Sierra Club’s board to vote in support of draining the lake. Then as now, the heart of the matter is water, and whether Lake Powell saves it or wastes it. At full pool, the lake annually boils off a half-million acre-feet, or 163 billion gallons, into the sweltering desert sky. Dropping the lake down 150 feet, says Bureau of Reclamation hydrologist Tom Ryan, would reduce surface area and get the water off sizzling flats into cool, shady canyons, saving 50 percent of what’s lost to evaporation. That savings represents 20 percent of the water Southern California currently diverts from the Colorado River every year—worth about $96 million.

That’s why water-hungry California politicians, including at least two Democratic congressmen, are exploring bills to direct the Bureau of Reclamation (which runs the dam) to keep the water at a lower level. Reluctant to go on record before the fall elections, their staffs hint that if the House tips to the Democrats, there may be hearings on the issue. Once the numbers get laid out, the thinking goes, it would be hard to oppose an everybody-wins scenario in which California gains cheaper water, the lake stays open for recreation, and adventurers get scores of new canyons to explore. Still, the challenge of lowering the lake isn’t just economic or technical—diversionary tunnels could drain it in a year. It’s emotional.

Over the last 40 years, a recreation economy centered in Page, Arizona, has sprouted along the edges of Lake Powell, in a region where jobs are as scarce as rain clouds. The $500-million-per-year business, built around houseboat rentals, is a way of life with its own advocacy group, Friends of Lake Powell, founded in 1997. FLP claims that draining the lake would jeopardize jobs, eliminate recreation, and cut off power produced by the dam, enough for 1.7 million people. “Glen Canyon Dam and Lake Powell are so ingrained here that it would be major heart surgery to try and remove it,” says Friends of Lake Powell board member Paul Ostapuk, 46.

Anticipating strong opposition, Ingebretsen plans to make sure that when the story line hits America’s living rooms, it’s about hidden splendors revealed, not the woes of personalwatercraft dealers. He’s now organizing a winter-long airlift of media into the newly opened canyons and hopes to hold a spring fundraiser in the Cathedral, believing that once the public sees what has been uncovered, they simply won’t allow it to disappear again.

Floating in the quiet grandeur of the emerging amphitheater, it’s hard not to get caught up in Ingebretsen’s optimism. At one point he stops talking, interrupted by a Jet Ski roaring by. He flags it down, and the motor dies. Waving a book of photos, this missionary for lost places calls out, “Hey, want to see a picture of this place before the lake? Come take a look!”