The New American Dream Towns

Welcome to the Neighborhood

We’ve found a new way of living

IMAGINE YOU HAD THE CHANCE TO INVENT A PERFECT TOWN from scratch. You could choose whatever features you wanted to make it a stimulating and satisfying place to live, and borrow liberally from the best of what other cities have to offer. Anything goes: You might start with French Quarter streets lined with painted-lady Victorians from San Francisco. Maybe a river runs through it, with bridges and banks very much like the Seine’s except for the Class III rapids in the whitewater park downtown. Solar-powered streetcars whisk commuters through lush greenbelts to art deco office towers, whose exterior walls double as climbing gyms. There’s free valet parking for bicycles on every block and a free-range chicken in every pot.

Creating an exquisitely livable town, of course, isn’t quite that simple. But it’s not a fantasy, either. When we combed the country for the sweetest innovations and the freshest ideas for making neighborhoods better places to live, work, and play with tons of green space, easy access to the outdoors, and big-think visions for smarter, more sustainable everyday living we hit the jackpot. Plenty of real American cities, we found, are taking positive steps to soften the rough edges of our high-octane day-to-day. Communities of all sizes are waking up and relearning old lessons: That many residents want the option of walking or biking to get from A to B. That locals will swarm to a town’s natural assets its shoreline or lakefront, riverbank or foothills if the paths and piers welcome them. And that change starts with a willingness to look hard at your weaknesses and then play to your strengths. Your town’s paper-flat, like Davis, California? Build a network of bike lanes and paths. It rains a lot in Portland, Oregon? Transform urban rooftops into gardens of native plants.

To spotlight the new American dream towns, we started with a wish list of criteria: commitment to open space, smart solutions to sprawl and gridlock, can-do community spirit, and an active embrace of the adventurous life. We looked for green design and green-thinking mayors, thriving farmers’ markets and healthy job markets. We found it all and then some: ten towns that might tempt you to box up your belongings, plus nine more whose bright ideas are well worth stealing. Check out these shining prototypes for what a 21st-century town what your hometown, perhaps can be: cleaner, greener, smarter. Better.

Salt Lake City, Utah

POPULATION: 182,000 // MEDIAN AGE: 30 // MEDIAN HOME PRICE: $204,300 // AVERAGE COMMUTE: 19.2 min.

When the mayor of the largest city in Utah uses his annual State of the City address to evangelize about sustainability, greenhouse-gas reduction, and the downsides of Wal-Mart, you know something’s brewing on the Wasatch Front. The speech, delivered in January by Rocky Anderson, a Democrat elected in 1999, is but one indication that Salt Lake City—a near-perfect location for avid outdoor adventurers—is gradually wriggling itself into the environmental forefront. In 2002, the city government independently latched on to the Kyoto Protocol goals, vowing to cut its emissions of greenhouse gases 21 percent by 2012. Light-rail lines, christened just in time for the 2002 Winter Olympics, reduce auto traffic by funneling 44,000 riders a day in and out of downtown, while the SLC sewage-treatment plant turns released methane into electricity to help run itself. All of this plays to mixed reviews in conservative Utah. “People who live in the city love [Anderson],” says Vicki Bennett, Salt Lake’s environmental- programs manager. “The state legislature hates him.” Politics aside, sunny SLC offers much more than its lingering Donny Osmond stereotype suggests—most notably, quick access to the Wasatch Range’s dazzling canyons and near-12,000-foot peaks.

PROGRESSIVE CRED // Compact fluorescents now light city offices, and traffic signals glow with energy-saving LED bulbs. Plans for a 1.2-million-square-foot west-side “sprawl mall,” as Anderson dubbed it, were tabled after opponents derided its dependence on car traffic and its threat to locally owned stores. On the negative side, because it’s tucked into a smog-collecting basin, air quality in the Salt Lake Valley remains alarming at times. But, hey, you gotta start somewhere.

LIVABILITY // Yes, you can buy a cocktail, and, no, not everyone is a Mormon. (Just under 50 percent of city residents belong to the Church of Latter-day Saints.) Salt Lake earns glowing reviews these days from dog lovers, vegetarians, bookstore browsers, microbrew guzzlers, and especially recreationists. Within an hour lie the crowd-pleasing powder stashes of Alta, Snowbird, Deer Valley, and backcountry chutes galore. Singletrack abounds in Big and Little Cottonwood and five other canyons, and the Provo River is thick with trout. The University of Utah, the LDS church, and Delta Airlines all employ big numbers.

YOU’LL LOVE IT IF // You think living in one of the nation’s most underrated outdoor meccas, in exchange for endless polygamy jokes from your out-of-state friends, is a pretty fair trade.

Littleton, New Hampshire

POPULATION: 6,000 // MEDIAN AGE: 39 // MEDIAN HOME PRICE: $153,000 // AVERAGE COMMUTE: 17.7 min.

It would have made a dandy plot line for a Frank Capra picture. Act One: Sleepy North Country burg nestled in the rugged White Mountains reels when 800 shoe-factory jobs vanish. Act Two: Plucky villagers—a mix of blue-collar workers and doctors, lawyers, and teachers—band together to breathe new life into struggling Main Street. Act Three: Vacant storefronts fill, Sunday farmers’ market draws crowds, downtown goes WiFi, and the place not only survives but prospers. What makes the story so compelling is that it’s all true—and it’s taken 30 years and a cast of hundreds to make it unfold. Among Littleton’s recent improvements are a walking path and bridge gracing the Ammonoosuc River, a high school project that brainstormed a way to heat downtown sidewalks in winter (by mixing furnace exhaust with water and glycol, then pumping it through underground tubing), and an effort by pragmatic downtown merchants to zero in on niches that the big-box retailers on the edge of town can’t fill. In short, it’s a cutting-edge model of economic revival overlaid onto a postcard setting.

PROGRESSIVE CRED // Littleton’s unofficial motto seems to be “It takes a committee.” Past and present ones include the Economic Development Task Force, the Riverwalk Committee, Envisioning Littleton’s Future, Littleton Main Street Inc., and—no doubt—more to come. But from those seeds have sprouted plenty of tangible assets: a 200-acre industrial park that accounts for upwards of 1,200 local jobs, a recent push to create more jobs for young people, one of New Hampshire’s top recycling programs, and 145 units of new or refurbished affordable housing. Sprawl is minimal, but so are open-space initiatives: Littleton’s still recovering from double-digit unemployment in the early 1990s, so—at least for now—development tends to win out over conservation.

LIVABILITY // Crime is low, and state sales tax and income tax are nil. The hospital was recently rebuilt, attracting M.D.’s and others from along the I-93 corridor between here and Boston, three hours south. Outdoor playgrounds? Take your pick of flatwater paddling on the Connecticut River, whitewater on the Ammonoosuc, cragging and hiking in the White Mountains, road and mountain biking in every direction, and skiing at Cannon Mountain—where World Cup ski champ Bode Miller learned to bomb.

YOU’LL LOVE IT IF // You don’t mind looking elsewhere for cultural diversity and, well, culture.

Fort Collins, Colorado

POPULATION: 126,000 // MEDIAN AGE: 28 // MEDIAN HOME PRICE: $220,500 // AVERAGE COMMUTE: 18.5 min.

This cottonwood-shaded college town in Colorado’s Front Range gets short shrift compared with its strenuously progressive neighbor to the south, but don’t call it Boulder Lite. Fort Collins has more than enough backyard wilderness and green bona fides to hold its own—with less traffic and cheaper real estate. Hometown cred starts with New Belgium Brewing—makers of Fat Tire Amber Ale—which runs its plant on wind power, uses only half the typical amount of water to brew a barrel of suds, and makes local deliveries in trucks fueled by a blend from Blue Sun Biodiesel, another homegrown company. Colorado State University delivers more paychecks than anyone else in town and helps set the eco-conscious tone, with its 212-acre Environmental Learning Center, situated on prime fox-and-heron habitat on the Cache la Poudre River, on the edge of town. CSU’s nearly 25,000 students keep things young and happening, and the lively and walkable Old Town district—with its smoke-free restaurants and bars, Friday-night gallery openings, and summer music and beer festivals—sweetens the mix.

PROGRESSIVE CRED // By buying and leasing 19,000 acres of former ranchland north of town near the Wyoming state line last year, the city locked in a key piece of the Laramie Foothills project, a massive public-and-private plan to keep 55,400 acres of critical wildlife corridor—linking the mountains and the plains—undeveloped. The city itself boasts some 4,300 acres of green space, along with 25 miles of in-town trails and 143 miles of bike lanes. Fort Collins’s Climate Wise program provides free consulting to 33 local businesses—from the Anheuser-Busch plant and CSU to natural grocer Wild Oats—on how to cut greenhouse-gas emissions; strategies include switching to biodiesel and increasing recycling. Three new sustainably designed schools feature solar panels and wind-generated electricity; a geo-exchange system will heat and cool a junior high slated to open next year.

LIVABILITY // Fort Collins’s population jumped 35 percent in the 1990s, and for good reason: Within a couple hours’ drive in every direction lies a ridiculous bounty of backcountry options, including crags and trails in Rocky Mountain National Park (just 40 miles southwest), singletrack in Lory State Park, Summit County powder runs, and whitewater on the Poudre. On the job front, Hewlett-Packard and Eastman Kodak anchor the tech-heavy base, which has suffered a flurry of recent layoffs. Health care, on the other hand, is thriving, and CSU has helped spawn a culture of innovation and dozens of startups: Optibrand’s electronic gizmos allow GPS tracking of cattle, and Able Planet’s devices enable the hearing-impaired to communicate by phone.

YOU’LL LOVE IT IF // You crave the mountains and can handle the fact that the Front Range boom has arrived—and shows no sign of stopping.

Charleston, South Carolina

POPULATION: 97,000 // MEDIAN AGE: 33 // MEDIAN HOME PRICE: $248,000 // AVERAGE COMMUTE: 20 min.

You can’t capture a sense of place and charm in a bottle, of course. But Charleston has come pretty close. In the past 30 years, this port city on the peninsula where the Cooper and Ashley rivers flow into Charleston Harbor has become a lively, subtropical magnet for young creative types, families, and the water-obsessed. The city’s revival has coincided with the 30-year mayoral tenure of Joe Riley, who, starting in the 1970s, spearheaded the redevelopment of a down-at-the-heels business district and the creation of lovely Waterfront Park, along the Cooper River. A model of cultural preservation, Charleston formed the nation’s first historic district, in 1931, to protect its narrow “single houses,” piazzas, and lush garden courtyards. Geography—especially the tracts of undeveloped marshland that beckon in either direction along the coast—also wields a powerful influence. “It’s easy to be a conservationist here,” says Dana Beach, of the South Carolina Coastal Conservation League, which is at work on land-use, water-quality, and forestry campaigns in the Charleston area. “People talk about it at cocktail parties. They see it as part of their heritage.”

PROGRESSIVE CRED // Keeping the waterfront accessible to all is an ongoing quality-of-life issue in Charleston; a four-mile promenade along the peninsula is 80 percent complete. Although battles over outlying growth and sprawl are heating up, a new county sales tax, passed in May, will fund public transportation and green space. The city has also pioneered scattered-site affordable housing, mixing low-income tenants with market-rate homes.

LIVABILITY // The economy’s sizzling: Next to tourism, the port (second-largest on the East Coast), the Medical University of South Carolina, and the military are major players, alongside a host of thriving startups: iPod accessories, software for nonprofits, and robot helicopters. On weekends, locals catch waves at Folly Beach, sail the harbor, and hike and bike among 300 bird species in Francis Marion National Forest.

YOU’LL LOVE IT IF // You think “approaching hurricane” is a quaint southern expression meaning “great surf.”

Davis, California

POPULATION: 65,000 // MEDIAN AGE: 25 // MEDIAN HOME PRICE: $333,000 // AVERAGE COMMUTE: 20.6 min.

If more developments resembled Davis’s Village Homes project, subdivision might not be such a dirty word. Trees shade the narrow streets, keeping the asphalt (and air) cooler during the hot Central Valley summers than in less enlightened housing tracts. Nearly 75 percent of the community’s 225 houses use solar power, reducing furnace heat in the winter. And it’s all linked by broad common spaces, winding pathways, and—here’s a term you don’t hear enough—”edible landscaping”: community vineyards and orchards yielding grapes, persimmons, cherries, almonds, and peaches. No town gives more leeway to bicycles: 51 miles of paths and 50 miles of bike lanes (among the first in the nation); special bike-traffic signals at intersections; even BikeTalk on KDRT-FM (K-Dirt). Citizen involvement is high on the list of civic values: Rush hour in Davis, goes a local truism, happens just before 7 p.m., when people are scurrying to their committee meetings.

PROGRESSIVE CRED // If you’re tall, dark, and herbaceous, this is your kind of town. Davis maintains a Landmark Tree List and a Master Street Tree List—as well as 31 parks, 20 greenbelts, and a 400-acre man-made wetland. To compensate for every acre of farmland built upon, developers must preserve two acres of comparable land in its place. Culture gets a nod, too: 1 percent of all capital-improvement funds is set aside for public art such as sculptures. And Central Park’s year-round farmers’ market, says Mitch Sears, Davis’s open-space planner, is “a community touchstone.”

LIVABILITY // UC Davis, which employs one out of every three residents, keeps the local scene young and diverse. Land trusts, nonprofits, and green research programs, such as the National Institute for Global Environmental Change, abound. Davis’s proximity to the Bay Area and the Sierra Nevada means that anything you can do on water, snow, rock, or dirt is never far away.

YOU’LL LOVE IT IF // In the standard American turf wars—bike vs. SUV, farm vs. strip mall—you always root for the underdog.

Portland, Oregon

Portland, Oregon

Urban bliss: Portland’s Japanese Gardens

Urban bliss: Portland’s Japanese GardensPOPULATION: 550,000 // MEDIAN AGE: 35.2 // MEDIAN HOME PRICE: $203,600 // AVERAGE COMMUTE: 23.1 min.

For more than three decades, Portland has been so green you could serve it as a side dish. And the unofficial capital of the Pacific Northwest ecotopia is still showing the rest of America what’s possible. “What would be total fringe in other cities approaches the mainstream here,” says 32-year-old Amy Stork, who moved to Portland nine years ago and has since morphed into a microcosm of the place. Stork pedals three miles daily to her communications job at the city’s Office of Sustainable Development. She attends bike-film festivals and bike-in movies, bike-hauls compost to her community-garden plot, and, when she must resort to four wheels, whips out her membership card at Flexcar, the popular car-sharing company. Portland is a magnet for people like Stork: college-educated twenty- and thirty-somethings looking for a progressive urban lifestyle. The city’s outdoor playgrounds don’t hurt either. Pacific sands, 90 minutes to the west, draw beachcombers and whale watchers; Mount Hood and the Columbia River Gorge, just an hour to the east, lure anyone who hikes, bikes, paddles, windsurfs, or skis.

PROGRESSIVE CRED // Green space? Check. Portland has 227 parks, including Forest Park, at 5,000-plus acres the nation’s largest urban wilderness. Bike-friendly? Emphatically, with almost 270 miles of street lanes and paths, all lovingly marked with nonskid paint. Walkable? Two-hundred-foot blocks, half the length of those in many cities, and narrow streets keep the scale human. Public transit? Yup: 44 miles of metro-area light-rail lines, and the country’s first new urban streetcar line in half a century, all free within a 330-square-block downtown grid. Hybrid cars? More per capita than anywhere else. Structures certified, or awaiting certification, by the U.S. Green Building Council? The most—no “per capita” needed. Almost too good to be true, isn’t it? But smug Portlanders better watch their backs: Measure 37, a private-property-rights law approved by Oregon voters last fall, makes it harder for government agencies to enforce the tight land-use rules that have so far curtailed sprawl.

LIVABILITY // On average, Portlanders spend more on reading material, watch more indie films, and grow more flowers than their countrymen. Portlanders drink better beer than most, too, with 23 microbreweries within city limits. The arts, performing and otherwise, are booming, and the 11 farmers’ markets help locals eat local. The city’s job market bottomed out two years ago, taking multiple blows in the key high-tech manufacturing sector, but that hasn’t slowed the flow of new arrivals.

YOU’LL LOVE IT IF // Job opportunities and rising home prices matter less to you than keeping it clean and green.

Chicago, Illinois

POPULATION: 2.7 million // MEDIAN AGE: 32 // MEDIAN HOME PRICE: $265,000 // AVERAGE COMMUTE: 33.2 min.

When Mayor Richard M. Daley (son of Richard J. “Boss” Daley, mayor from 1955 to 1976) first declared his vision of transforming gritty, sports-fixated Chi-town into “the greenest city in the country,” residents smirked and ordered another pitcher of Old Style. Now, with Daley in his fifth term, skeptics are about as common here as Mets fans. Under Daley’s reign, more than 400,000 trees have been planted, 125 vegetation-covered “green roofs” have sprouted atop buildings—including City Hall—to slurp up runoff and help cool the urban heat island, and dozens of new energy-scrimping structures are in line for certification by the U.S. Green Building Council. The city has teamed with local environmental groups to give four run-down South Side bungalows sustainable makeovers (recycled-tire floor tiles, geothermal heating)—a project designed to inspire owners of 80,000 similar vintage nests across the city. Meanwhile, architects and gardeners attend free workshops at the city-funded Center for Green Technology; abandoned gas stations have blossomed into pocket parks; and the Field Museum has gone solar. The belle of Chicago’s renaissance? Millennium Park, 24.5 downtown acres of gussied-up railyards and parking lots, complete with a bike-commuting station, an ice rink, and a Frank Gehry–designed band shell.

PROGRESSIVE CRED // Still not convinced? Consider the fact that the city government is on track to buy 20 percent of its power from renewable sources within the next year and that 4,800 acres of recovering South Side wetlands will soon host a center for environmental remediation. Homeowners who upgrade the energy-efficiency of historic homes earn up to $2,000 in grants. The city will even let you swap your exhaust-spewing gas lawn mower for a discounted electric model. These guys are serious.

LIVABILITY // In addition to the 18-mile string of parks and beaches along Lake Michigan (which fill with volleyball players, runners, and sailors as soon as spring even hints at appearing), ambitious new outdoor visions are taking shape, including the Grand Illinois Trail, a 537-mile bike loop to the banks of the Mississippi and back, and the Northeastern Illinois Regional Water Trail, a 467-mile network-in-progress of lake and river routes for kayakers and canoeists. Economic bonus: The diversity of Chicago’s job market tends to prevent jarring spikes and plunges.

YOU’LL LOVE THIS TOWN IF // You can look past the dismal winters—because no city packs more living into its summer.

Madison, Wisconsin

POPULATION: 208,000 // MEDIAN AGE: 30.6 // MEDIAN HOME PRICE: $223,000 // AVERAGE COMMUTE: 18.3 min.

It’s easy to fall for Madison. Wisconsin’s capital is like a girl who aces all her finals, paddles a mean J-stroke, knows how to tap a keg, and doesn’t realize she’s a knockout. (Oh, yeah, she can also milk a Guernsey.) The appeal starts with location. The town sits on a two-mile-long isthmus between Lake Monona and Lake Mendota, rippling expanses perennially dotted with sailors and paddlers (or ice-fishers and ice-yachters, depending on the season). A city-sponsored 30-mile web of paved trails—well lit, snowplowed, and biked year-round—combines with walkable streets and first-rate bus service to make car-free commutes viable; there’s even a Paddle to Work Day, in June. Along with its natural assets, Madison offers myriad urban pleasures: thriving co-ops, ethnic menus, clever entrepreneurs, and all the other trappings of post-hippie capitalism. The University of Wisconsin’s 900-acre flagship campus, 40,000 students strong, is a microcosm of the larger populace—brainy and left-leaning, tolerant and determinedly unprovincial. Factor in a dozen or so beaches, some 250 parks, Big Ten athletics, and an enormous farmers’ market and you’ve got the complete package: Berkeley with bratwurst.

PROGRESSIVE CRED // Madison has a long heritage of open-mindedness. It was the first U.S. city to launch curbside recycling (in 1968); today, there are waiting lists for residents who want Madison Gas & Electric to supply a portion of their electricity via wind power. More than 70 percent of Madison’s traffic signals run on energy-saving LED fixtures, and Mayor Dave Cieslewicz is determined to keep green space a priority: He’s vowed to open five new parks a year—maintained, of course, without chemical pesticides or fertilizers—and he’s kept that promise during his first two years in office. Wisconsin ranks third in the nation in number of organic farms, and community-supported agriculture—a system in which consumers buy “shares” of a local farm and the food it produces—are high on the Madison agenda.

LIVABILITY // Madisonians are wired and literate; last year Forbes called the city a “seedbed of biocapitalism” for launching 120 biotech firms in the past decade. Largely because of UW’s influence, startups and spinoffs are common. A cross section of innovative Madison companies: Epic Systems (medical-records software), Cellular Dynamics International (stem-cell research), and Planet Bike, a cycling-gear outlet that donates a quarter of its profits to velo-friendly causes. Houses are still reasonable, although last year the area’s median sailed past the $200,000 mark.

YOU’LL LOVE IT IF // You like your mom-and-apple-pie, cheesehead midwestern vibe served with a shot of coastal hipness.

Pasadena, California

POPULATION: 146,000 // MEDIAN AGE: 34.5 // MEDIAN HOME PRICE: $509,200 // AVERAGE COMMUTE: 25.9 min.

Los Angeles County’s unholy trinity of smog, sprawl, and gridlock long ago earned it the stamp of America’s paradise lost. But some eye-opening changes are unfolding, many of them in this revitalized urban village at the foot of the San Gabriel Mountains. A satellite on the northeast side of L.A., Pasadena is an experiment in downtown revitalization, smart planning, and life beyond car addiction. Since the Metro Gold Line light-rail train opened in 2003, linking the suburb with downtown L.A., Pasadena has become a hub for innovative mixed-use development, with 800 new residential units. This isn’t pop-up suburbia, though. The city’s pedestrian-welcoming streets—shaded by an exotic canopy of 286,000 California oaks, jacarandas, and palms—are famously home to a mother lode of Craftsman architecture, as well as a gallery of races and languages (a third of Pasadenans are foreign-born; more than half are Hispanic, black, or Asian). Once blighted Old Pasadena, a 21-square-block historic district, is now one of the Southland’s hottest nightlife magnets.

PROGRESSIVE CRED // The city is removing hundreds of tons of concrete debris and planting native sycamores and oaks to restore streamside habitat in Arroyo Seco, a 132-acre gulch harboring a web of trails and the Rose Bowl Stadium—along with a small population of coyotes and bobcats. Human habitat is getting attention as well: The nonprofit Heritage Housing Partners helps first-time home buyers, provided that they protect their house’s architectural character. The city offers substantial rebates for solar-power installations, and Pasadena Water & Power recently inked a long-term deal to buy electricity from California’s largest wind farm.

LIVABILITY // Take your pick: highbrow visuals at the Norton Simon Museum, Pacific Asia Museum, and Pasadena Museum of California Art; edgy performances from the Furious Theatre Company; readings at Vroman’s Bookstore; or an alphabet’s worth of dining options (Afghan, Brazilian, Cuban . . . ). You can surf in nearby Malibu, fly-fish in Angeles National Forest, and hoof it down the Pacific Crest Trail—all without leaving metro L.A. Within a few hours, you can climb in Joshua Tree, snowboard in the San Gabriels, or paddle the Kern River—which raged this spring with the torrential runoff of the biggest Sierra snowpack in years.

YOU’LL LOVE IT IF // You’d like a little bit of Paris on the 210 Freeway and don’t mind the sensation of property values inflating beneath your feet.

Portland, Maine

POPULATION: 64,000 // MEDIAN AGE: 36 // MEDIAN HOME PRICE: $215,000 // AVERAGE COMMUTE: 19 min.

Portland’s centuries-old maritime heritage isn’t just a brewpub decorating motif. Thanks to a 1987 referendum that tightened restrictions on waterfront development, it’s a workaday reality. Yachts, catamarans, and cruise ships ply Casco Bay’s natural harbor alongside fishing fleets and tugboats hauling in oil tankers. And the pedestrian traffic in the adjacent Old Port district, a bustling brick-and-cobblestone mix of locally owned restaurants, offices, and upper-story apartments, suggests that different worlds can overlap: landscapers, lawyers, and lobstermen all coexisting. As far as after-work diversions go, few towns of this size could even dream of rivaling Portland’s options. A well-used network of paths and greenways, many right along the shoreline, continues to expand, and 486 restaurants within city limits feed the oft repeated rumor that only San Francisco can claim more per capita. Crime remains low; the number of sea kayaks strapped to car roofs, reassuringly high.

PROGRESSIVE CRED // This summer, Portland Trails will complete a 30-mile network of foot- and bike paths that’s been years in the making; waterfront sections along the Eastern Promenade and Back Cove will become part of an envisioned 3,000-mile urban path stretching from Calais, Maine, to Key West, Florida. Infill development is poised to take off, with downtown’s progressive Bayside neighborhood soon to trade in its warehouses for $60 million in offices, shops, homes (including affordable units), and walkable streets—a model of urban density. Meanwhile, the city’s zeal for nurturing small businesses dovetails with an influx of newcomers. You might not expect a Somalian grocery or a Cambodian market in Maine, but they’re here. Other accolades: an aggressive recycling program, low-emissions power plant, and sustainable school.

LIVABILITY // Portland’s job market is sunnier than its coastal New England climate. Health care, banking, insurance companies, shipping, biotech, tourism, L.L. Bean (15 minutes up the coast), and semiconductors keep unemployment low. Startups are a Portland staple, with all manner of city-leveraged loans, tax-increment financing, and walking success stories to egg on transplants. Athletes go inland for climbing and skiing in the White Mountains and to the Atlantic for sailing, sea kayaking, and chilly surfing. “Hypothermia is a real danger,” cautions the local Surfline report, “as is severe shrinkage.” Noted.

YOU’LL LOVE IT IF // You prefer a smaller, cheaper, and somewhat sleepier alternative to Boston.

Smart Urban Ideas, PT. I

best towns

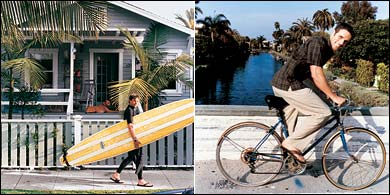

MAKE YOURSELF AT HOME: Small-town thinking in Venice.

MAKE YOURSELF AT HOME: Small-town thinking in Venice.Smart Idea #1

• Big Pine and No Name Keys, Florida

When your island is four miles wide and happens to be a habitat for endangered species, MANAGING DEVELOPMENT isn’t just smart—it’s imperative. To protect the vulnerable Key deer and stave off Key Largo–like growth, Big Pine and No Name keys, with a combined population of 5,000, approved a community plan this spring that limits the construction of new homes to ten per year (minimizing their impact by concentrating them along the U.S. 1 corridor), purchases empty lots for open-space conservation, and restricts the size of retail stores in support of smaller mom-and-pops.—Melinda Mahaffey

Smart Idea #2

• Venice, California

Despite being enveloped by a teeming metropolis, this L.A. neighborhood of 34,000 is blessed with ocean views, a small-town vibe, and SUSTAINABLE ARCHITECTURE. Among those designing in Venice are Isabelle Duvivier, whose firm won a 2004 Santa Monica Sustainability Leadership Award; eco-designer David Hertz; and modernist icon Frank Gehry. And Venice’s green scene goes beyond the built environment: Duvivier is currently working with the state on an interim management plan to preserve the Ballona Wetlands, the last remaining large-scale wetlands in Los Angeles County.—M. M.

Smart Idea #3

• Auburn, New York

This trout-fishing haven of 28,000 near upstate New York’s Lake Owasco is staging a RENEWBALE ENERGY revolution. In 2003 the city retrofitted its 75-year-old municipal building with a geothermal heating system designed to cut CO2 emissions by 58 percent and save an estimated $19,000 a year.—Jason Stevenson

Smart Idea #4

• Santa Fe, New Mexico

The juniper-covered foothills just east of downtown Santa Fe (pop. 66,000) are a patchwork of private and government lands, making the creation of PUBLIC RECREATION SPACE a negotiating and fundraising nightmare. But local banker and conservationist Dale Ball, 81, plunged in anyway, raising more than $200,000, establishing rights-of-way with homeowners and—over the course of a dozen years—convincing officials to piece together tracts of city, county, and federal land to complete the 25-mile maze of singletrack that bears his name. Next up: the purchase of 103 acres to preserve the area for trail expansion.—J. S.

Smart Idea #5

• Marquette County, Michigan

This adventure mecca on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula is home to an elaborate network of bike, ski, and kayak trails, as well as a GRASSROOTS HEALTH CARE initiative that matches uninsured residents with medical care and prescription drugs donated by doctors, hospitals, and pharmaceutical companies. Thanks to state and federal grants, more than 2,000 people have enrolled in the program; a similar model will be implemented across the rest of the UP by 2007.—J. S.

Smart Idea #6

• Montgomery County, Maryland

Just across the Potomac River from sprawl- and mall-choked northern Virginia is Montgomery County’s Agricultural Reserve, 93,000 acres of farmland that’s been protected since 1980. Twenty-five years later, the densely populated county of 920,000 is a national leader in OPEN-SPACE PRESERVATION, developing a ten-year, $100 million plan to protect vulnerable wildlife habitat, watersheds, and historic properties.—J. S.

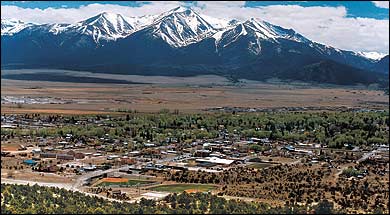

Smart Urban Ideas, PT. II: Buena Vista, CO

Buena Vista, Colorado

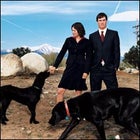

BUENA VISTA KAYAK CLUB: Developers Katie and Jed Selby with their dogs Hurley (left) and Charlie

BUENA VISTA KAYAK CLUB: Developers Katie and Jed Selby with their dogs Hurley (left) and Charlie���ϳԹ��� by Design

Building the town of the future from the river up

THE PLAN WAS AS BOLD as running a Class VI rapid in water wings: Buy a 40-acre parcel of premium Rocky Mountain property with more than 670 feet of river frontage and create a small-town utopia—complete with a half-mile-long whitewater park, live/work spaces, restaurants, bike trails, and tree-lined avenues of shops, coffeehouses, art galleries, and theaters.

“It seemed crazy at first,” says Katie Selby, 29, a pro kayaker who, with her 26-year-old brother, Jed (also a professional paddler), is spearheading one of the most ambitious—and, arguably, enlightened—development projects in the West: South Main, in Buena Vista, Colorado, a bucolic burg framed by snowcapped fourteeners to the west and high-desert hills to the east. “I was living up in Alaska, paddling, chasing moose and elk around, and Jed kept calling me and pushing the idea, keeping it alive.”

Though Jed had settled in central Colorado for the nearby paddling, he wasn’t spending much time there. “I was driving all around North America, going to competitions, sleeping in the back of my Subaru, eating fast food,” he says. “I just started questioning the whole lifestyle. When this idea began to take hold, I thought, Now I can really make a difference.”

The Selbys had grown up in Tucson, Arizona, and both attended Fort Lewis College, in Durango, so they’d witnessed the West’s rapid urban growth firsthand. When Jed first laid eyes on the undeveloped, trash-strewn field between the Arkansas River and Buena Vista’s 100-year-old historic district, he immediately saw its potential. At the time, it was pegged as the future home of dozens of McMansions that would have shut out public river access. But in 2003, with help from their father, Buzz, a Tucson-based doctor and real estate investor, the siblings came up with the winning $1.2 million bid and purchased the land. Their next step: nailing down a design for their urban hamlet.

For that, the Selbys—with the help of Florida-based design firm Dover, Kohl & Partners—embraced the principles of New Urbanism, which advocates densely packed, mixed-use, pedestrian-friendly development as an alternative to sprawl. In South Main’s case, that means leafy avenues with gable-roofed Arts and Crafts–style bungalows, quaint frontier Victorian row houses, awning-shaded storefronts, sidewalks, picket fences—it’s Bedford Falls, only populated by kayakers in flip-flops hanging at the coffee shops after thrashing sculpted playholes. The design also includes a riverside park with bike paths, beaches, and a village square surrounded by a retail hub. The remaining space is platted for residential lots (about 200 in all), ranging from $40,000, for a standard row-house lot, to $70,000, for a 5,000-square-foot chunk of land for a single-family home—a bargain compared with prices in nearby Summit County.

While the Selbys will oversee development of the river park and green space—underwritten largely by a $187,000 grant from the state’s open-space preservation fund, Great Outdoors Colorado, and $30,000 from the city of Buena Vista—private developers will build the homes and businesses, following strict community guidelines. That commercial phase is still a couple of years down the road, says Katie, but reservations for lots in Phase One have been brisk: 24 of the first 26 lots were snatched up within two months of going on sale last spring. Bill Dobson, the realtor handling the project, says he already has a waiting list of 45 people, from young paddling enthusiasts buying a first home to retirees looking to downsize out of their country estates.

That all means a potentially lucrative investment for the Selbys, but the siblings insist the real payoff isn’t cash. “Money is just a means to an end,” says Katie. “Suburban sprawl is the source of pretty much all the problems that confront our country, from dependence on fossil fuel to water and air pollution to traffic congestion to ecosystem destruction. What’s more fulfilling than devoting yourself to solving the biggest issue out there?”