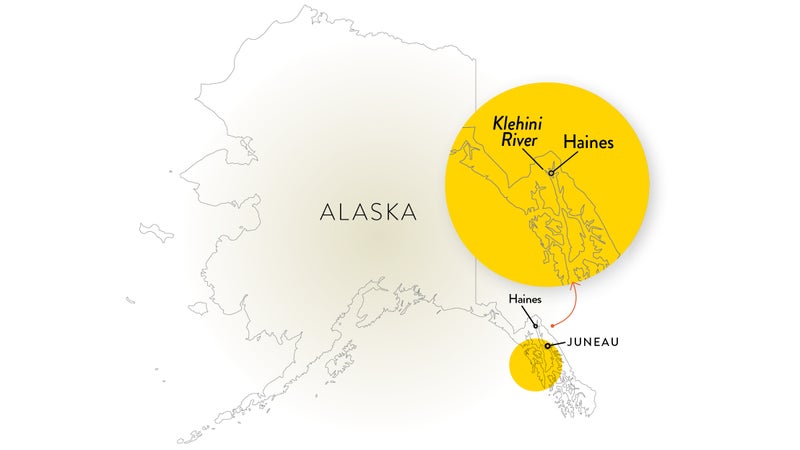

The Klehini River, a tributary of the Chilkat, one of Southeast Alaska’s major rivers, is home to runs of all five Pacific salmon species. It’s beautiful country, with a bald eagle preserve nearby. “Every animal you associate with Alaska lives and thrives in the Chilkat floodplain,” says staff scientist Guy Archibald.

For these reasons, Archibald and his colleagues at SEACC have been campaigning against the Constantine mine, an exploratory copper, zinc, gold, and silver operation above the Klehini River, just outside the town of Haines, Alaska. Mining would produce tons of sulfur waste, which reacts with water to create sulfuric acid, a powerful toxin. The disruption could have a big impact on tourism as well. Archibald fears 50-ton rock trucks roaring down the Haines Highway and rock crushers visible from fly-fishing spots. Add it all up, Archibald says, and “this is the wrong mine in the wrong place.”

Getting people to take notice, however, takes money—and, perhaps most important, arresting photography. “Having images is really key in getting our message across, especially in an age with so much information coming at us and competing with other organizations,” says Bryn Fluharty, SEACC’s communications and online coordinator. “A good photo draws so many more people in than if you don’t have one. It’s the connecting piece that says ‘This is here and this is real.’ ” When , a company that specializes in innovative camera gear, was looking for more ways to donate as One Percent for the Planet members, they realized they were sitting on a valuable network of photographers who could help grassroots environmental groups up their media game. Thus, the company established the program, in which photogs looking for volunteer opportunities can partner with One Percent for the Planet–associated causes that need images or video for campaigns, newsletters, or reports.

Imagery has long helped fuel conservation efforts. In fact, most major environmental movements have been fueled in part by powerful pictures. Drawings and photos of the Yosemite Valley accompanied John Muir’s soaring prose, helping solidify protection for the future national park. Threatened with energy development in the 1960s, the Grand Canyon remains dam-free today in large part thanks to the Sierra Club and David Brower’s stunning images. And images like Earthrise and Blue Marble, taken during the Apollo Missions to the moon, put the scale and fragility of our planet on show for the first time, helping establish Earth Day.

Launched last April, Give a Shot has already matched 150 media professionals with organizations in need of some Instagram-worthy shots. The program has helped groups working to protect the Oregon coast and Southwest archaeological sites including Colorado’s Mesa Verde. Recently, Rob Zeigler, a photographer who volunteered with the San Juan Citizen’s Alliance in New Mexico’s Greater Chaco area, launched the Faces of Chaco campaign, a photo essay connecting the people of the region to sacred sites imperiled by energy development. Which brings us back to Alaska.

“A good photo draws so many more people in than if you don’t have one. It’s the connecting piece that says ‘This is here and this is real.’ “

This past August, Give a Shot sent a volunteer expedition to Haines to raise awareness of the proposed Constantine mine, giving a voice to the people and ecosystems that would be catastrophically affected by the development. Not only did they document the environment, the volunteer crew chronicled the story of the locals whose families have lived in the area for thousands of years. “They photographed people with their histories carved into totems and stories woven into blankets,” says Archibald. “I think that’s very powerful.”

Peter Dering, founder and CEO of Peak Design, says he recognizes the irony of a company opposing a mine that produces some of the natural resources, like metals, it relies on to create its products. But he says both consumers and producers of raw materials need to be thoughtful about sourcing. “We’re not anti-economy or anti-world,” he says. “We understand that mining is necessary to live in the modern world. But we don’t need metals from this source.”

Dering hopes Give a Shot will inspire other brands to find projects that resonate with their core competencies as well. “Part of our mission is to try and get other companies to think creatively about their areas of expertise,” he says. “It’s a way to clean up the mess we inherently make by making stuff.”

Give A Shot

To learn more and see additional images from Peak Design’s volunteer expedition, visit . For more information about the Give a Shot program, please visit .