At the end of last summer, a close friend of mine, Zoe, snagged a permit to hike the 215-mile John Muir Trail, which runs along the spine of the Sierra Nevada. To prepare, she and a friend loaded up for a four-night backpacking trip southeast of Yosemite National Park.

“Wildfires weren’t really on our radar,” she told me this year. There hadn’t been any fires in the area when they headed out. “But we were up pretty high. When we saw a flat cloud on the horizon, it kind of crossed our minds—maybe that’s smoke, maybe not.”

As the day continued, they started to smell fumes and passed a couple who confirmed that there was a fire somewhere ahead, so they headed back the way they’d come and set up camp for the night, with plans to finish their retreat the next day.

“When we got up the next morning, we were totally engulfed in smoke,” Zoe said. “We woke up coughing. The sun was really red, and it was hard to breathe.” She wore a mask and a buff on the way down��to the trailhead.��

As it turned out, they’d stumbled onto the first days of , which became the fourth-largest fire in California history at the time. (It’s been surpassed by this year’s Dixie Fire.) It wouldn’t be contained until New Year’s Eve and burned close to 400,000 acres. By Zoe’s estimation, they were some 25 miles from it.��

If you’ve ever gone backcountry skiing, sea kayaking, or floated down whitewater, you’ve planned around natural hazards. You’ve researched terrain, checked dam releases, tide charts, or avalanche reports. You’ve learned to use a beacon and probe or to set up rescue lines.

With wildfire season stretching nearly the entire year in parts of the Southwest, and massive, unpredictable fires becoming common in California, Oregon, and Washington, it’s clear that hikers and backpackers need to treat fire risk in the same way: as a fundamental part of a trip plan, not an afterthought.

But it’s probably not something you were taught, since conditions have changed so dramatically in the past few years. So we talked to land managers and trail groups for their advice on how to plan for fire in the backcountry.

Where to Go��

“First and foremost, know where not to go,” said Kindra Ramos, outreach director with the nonprofit .

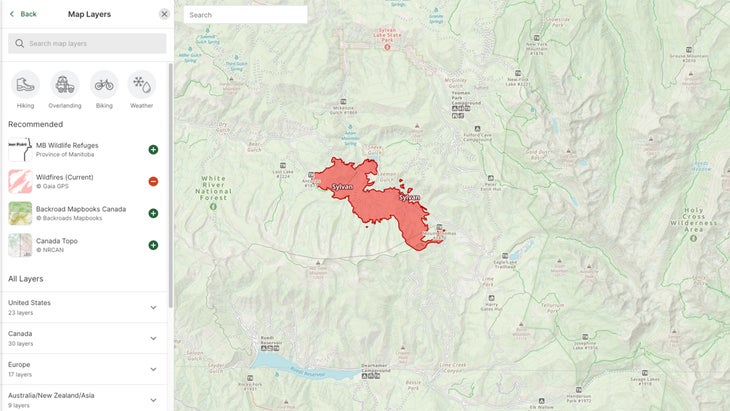

Many online hiking maps now include details on active fires. The has a fire layer that includes fire data across the Mountain West. (You access it by clicking the three stacked squares in the upper-left corner of the map.)��

“I think that drawing a parallel with avalanche risk is an intuitive way to think about it,” said Ben Mayberry, a recreation and land-use manager with the Washington Department of Natural Resources. “It’s these layers that stack on top of what you’d normally think about. You have to completely reframe, and focus on what the terrain is like, how it influences risk.” Still, he cautioned, “the big caveat is that avalanches are much more of a science that can be well understood. Wildfires are more unpredictable—would you try to plan around a hurricane or a tornado?”

For more in-depth fire information, includes a number of add-ons, including one for visualizing fires, as well as others that show satellite-detected heat layers and the location of historic fires. (Gaia GPS is owned by the same parent company as�����ϳԹ���. for free.)

Smoke Prediction

In the past few years, some tools have appeared to help monitor and even predict the air-quality index, a measure of airborne particulate matter. An above 100 will likely be harmful to someone with asthma or other health conditions, while 150 is harmful to anyone.

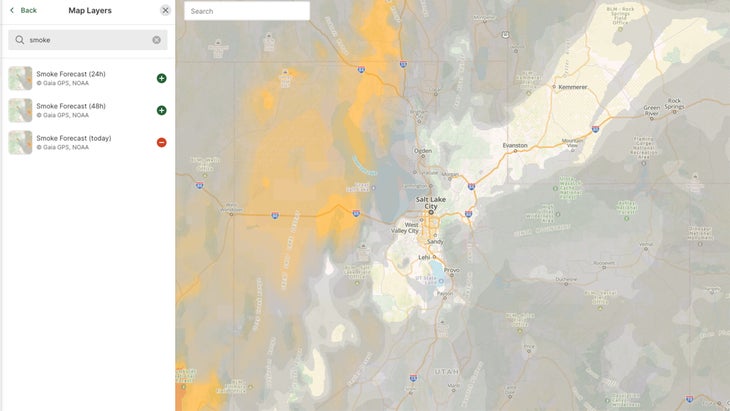

The Pacific Crest Trail Association’s map includes a smoke layer, and others are available on Gaia GPS. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration also produces a that provides state-by-state maps, though it only projects out for the day. (You’ll want to look at maps of surface smoke, since the tool maps multiple pollutants.)

For longer-term information, try . It includes major fires all across North America and forecasts smoke levels roughly two days out.

“It may be that it’s not a good time to hike, because there’s so much wildfire smoke or things are changing so quickly,” says Mayberry.

He, like Zoe, says he’ll be backpacking with an N-95��mask. “But it’s interesting. If we had not been wearing masks for the past 18 months, would that be something we’d be reaching for?” he said. “I think, separate from COVID, I would not have thought of carrying an N-95. I would feel more like, Clearly I shouldn’t be out here if I have to wear a medical mask.”

After walking out of the Creek Fire’s smoke, Zoe said that she canceled��her John Muir Trail plans. “The Sierra��were on fire,” she said. “It sucks, but there’s nothing you can do about it. It’s pretty dumb to push on. Some people will continue to hike in smoke, and I saw people doing that, but what’s the point? You can’t see far. The views aren’t as good.”

Planning the Route��

Once you’ve picked an area that’s smoke- and fire-free, check with local agencies for any trail closures or burn restrictions, which will help you pick a route and give you a sense of the area’s potential fire danger.��

“Trail closures often begin and end many miles from a fire,” said Scott Wilkinson, director of communications for the Pacific Crest Trail Association. “This is done for good reasons. Either firefighters want to ensure nobody could impede their efforts, or because the best place to get off the trail may be miles away from the fire itself. For all these reasons and more, it is imperative that hikers obey trail closures—and don’t look around and keep walking because they don’t see any smoke or flames.”

Bring a paper map that shows the entire area, urged the Washington Trail Association’s Ramos. (And be comfortable navigating with a map and compass.)��“Make sure that you have the big picture of where you’re going, so that if you need to plan an alternative route off-trail, you have the right map.”

You should also use the map to get a general sense of where evacuation routes might be: look for trails along the route where you could cut over to a road, or otherwise cut the trip short and find help.

And the more days you’re out, the riskier things get, simply because you won’t have up-to-date information.

“On longer trips, I think it’s always a good idea to carry some kind of satellite communicator,” Mayberry said. That way, if you spot smoke, or the air quality gets bad, you can text a friend for current information that might help you plan an evacuation.

Of course, that means telling someone where you plan to be and making sure they know which websites to check. If you’re going on a long hike or an overnight trip, you should also let local rangers know your itinerary in case conditions abruptly change and they need to evacuate the area.

What to Do if You Encounter a Wildfire Threat on the Trail��

Finally, you need to be comfortable bailing if conditions get too bad.

“It’s about having that situational awareness,” Ramos said. “If you are all of a sudden smelling more smoke or seeing smoke, I think that’s a clear indication that something has changed in the area, so you want to be comfortable leaving at that point.”

If you find yourself near a fire, take time to gather information.

“The only thing I’m really comfortable with recommending is communicate with someone,” Mayberry said. Use a satellite device to get a report on where the fire is and where it’s moving so you don’t end up heading into it.��

If you do end up in a dangerous situation despite taking all the precautions, how you should evacuate will depend enormously on the terrain and state of the fire. But there are . Fire generally moves fastest uphill, so avoid staying on ridges above any flames. Stay away from chutes, as these will channel flames upward. The less vegetation an area has, the safer it will be. Move out of a fire’s path, if you know it—you won’t be able to outrun one that’s moving fast. And if you have bright clothing or gear, put it on to make yourself visible to first responders.

But if you’re up on to date on the latest conditions, and you’re prepared to turn back at the first indication of smoke, the experts I spoke with believe your chances of getting into an emergency situation are slim. Take “that extra moment to realize that your safety shouldn’t be at risk for a great view,” said Ramos. “There’s always another day, and the trail will be there.”��

to plan your hike in clean air, away from wildfires.