When it comes to writing about a subject that’s so bleak and depressing that commercial failure seems all but guaranteed, it’s hard to beat the book that Michael Ghiglieri, a longtime Colorado River guide, was finishing up in the spring of 2001. His 408-page manuscript chronicled, in chillingly graphic detail, the many ways in which more than 600 people have met an untimely and traumatic end in the Grand Canyon.

Nicaragua

Nicaragua

Nicaragua

Nicaragua

Feeling certain that they wouldn’t find a publisher to back such a macabre project, Ghiglieri and co-author Tom Myers┬Śa physician who’d spent ten years treating patients on the Canyon’s South Rim┬Śdecided to pony up $45,000 in printing and production costs and release it themselves. They both tapped their savings, loaded up with books, and hit the road, distributing copies of Over the Edge: Death in Grand Canyon to bookstores, roadside caf├ęs, and shopping malls in Arizona and Las Vegas.

“It was pretty humbling,” recalls the 60-year-old Ghiglieri. “It felt like we were two 14-year-olds looking for our first bag-boy jobs at the grocery store.”

The book swiftly found its audience, though, and by this spring Over the Edge was headed for its 17th printing, having sold more than 150,000 copies and become the bestselling item at the bookstores on the South Rim. It was the dark-horse publishing success story of the outdoor world, and this month Ghiglieri┬Śwho earned his Ph.D. studying chimpanzees in Uganda and is affectionately known to his fellow Canyon boatmen as “the Doctor”┬Świll extend the brand to include a park that, like Grand Canyon, is a notorious death trap for unwary tourists and adventurers.

Off the Wall: Death in Yosemite, which Ghiglieri co-wrote with former National Park Service superintendent Charles “Butch” Farabee, is due out in late May. Like Over the Edge, Off the Wall is carefully organized according to the various ways one can bite the dust in the backcountry. In addition to rock falls, airplane accidents, and boating debacles, the books offer a rich smorgasbord of drownings, climbing errors, murders, tree falls, suicides, flash floods, BASE-jumping mistakes, and random disappearances.

The stories evoke grisly fascination, but they also serve up important don’t-be-this-guy lessons that, Ghiglieri hopes, might reduce the number of tragic mishaps taking place inside the parks. We caught up with the Doctor this spring to talk about his research, and about how good things can come from studying very, very bad accidents.

OUTSIDE: Would it be fair to say you’re completely obsessed with death?

GHIGLIERI: I’m not obsessed with death at all┬Śin fact, I’m so unobsessed with death that I never want to do another book like Over the Edge or Off the Wall again. What I am kind of obsessed with is prevention, especially when so many of the accidents chronicled in both books are completely avoidable. It’s fair to say I became obsessed with that.

That’s really why you wrote them?

Yes. I’ve been a river guide for 34 years, and I was struck by the fact that people were getting killed and maimed in Grand Canyon and Yosemite every month of the year, yet back in the early days, nobody seemed to know or care about what, specifically, was going wrong. Records were kept, of course, but the files were often just thrown into a box somewhere and forgotten. So I thought it would be a good idea to gather and correlate this information and then look for patterns. In the process, I discovered it’s actually kind of fun to learn about this stuff. Especially if, you know, you’re not the one getting killed.

How did you get your hands on all this information?

The primary source was the Park Service’s own Incident Reports, but frequently the old reports were incomplete or lost or had simply been thrown away. So we looked in the county sheriffs’ reports, we read the complete microfilm records of every newspaper in northern Arizona and around Yosemite, we combed through all the history books, and we conducted extensive interviews. It was a pretty exhaustive process that, with each book, took about three years┬Śa search for diamonds among the pebbles.

Can we really “learn” from these stories?

Absolutely. And some of the lessons are surprisingly simple and obvious. For example, one thing that amazed me was the number of folks in Yosemite who have insisted┬Śand still insist┬Śon wading into rivers just above the park’s gigantic, thousand-foot-plus waterfalls. The streambeds up there are incredibly slippery. You’ve basically got an invisible coating of snotlike algae covering a surface of highly polished granite that has water washing over it at 13 miles an hour. Which means that if you slip, you’ll travel 40 feet in about two seconds, and then you’re over the edge and gone. Yet people continue to wade out there┬Śapparently they just can’t make the computational reality switch from suburbia to the real world┬Świth absolutely horrible results.

It was a financial gamble for you to publish these books. What made you think people would want to read this stuff?

Look, if I had written a book called, say, Death in the City that outlined all the ways you can die in a really bad neighborhood┬Śgetting shot, getting run over, and so on┬Śalmost no one would buy the thing. But three or four million years of evolution have programmed us to pay attention to big, scary things that can hurt you in the natural world┬Śstorms, avalanches, glaciers, rapids, nasty animals, whatever. Every one of us has at least one ancestor who was eaten by a bear. Those are the kinds of threats that twang an atavistic nerve. We’re supposed to pay attention. That’s how you wind up not being the guy who gets eaten by the bear.

And yet┬Śthe dining habits of bears aside┬Śsome of this is actually quite funny, isn’t it?

You know, unfortunately, it is funny. There’s a lot of stuff in these books that’s just Darwin Award material, and it can be horribly entertaining to realize that “Oh, my God, I belong to a species with a huge range of intellect … and that’s the low end of the spectrum right over there.” Some of these incidents are almost an embarrassment to Homo sapiens. At a certain point, you begin to realize that the average squirrel possesses more intellect than the average human being.

Really?

People do some of the dumbest things you could imagine, things that no other species would ever do. How about Shane Kinsella, a Yosemite tourist from Ireland? After drinking one hell of a lot of wine in August 2005, he poses for a photo in which he’s pretending to fall into the river just above Upper Yosemite Falls, which is a 1,430-foot drop. The shot doesn’t work out, so his friend┬Śwho’s also been drinking a hell of a lot of wine┬Śtells him to do it again. Shane obliges, only this time he loses his balance for real, falls in the river, shoots off the lip of the waterfall, spins into space, and, when he hits, explodes into pieces like a ripe melon. Only a human being┬Śnot even an amoeba┬Śwould make that mistake.

Do these stories ever bum you out?

Oh, yeah. It’s just awful, doing the research and reading through hundreds and hundreds of accounts of terrible things that people have done to themselves. But the whole process is kind of double-edged. On the one hand, I’m depressed by all these fatalities. But then, if two or three people who happen to read one of the books end up not doing something that might otherwise have killed them, I’ve done a good thing and saved a life.

Has anybody ever been upset by what you’ve written?

I was expecting to get a lot of “how dare you!” letters from readers of Over the Edge, but we got zero. In fact, it was just the opposite: We got letters from many people, especially relatives of those who died, expressing gratitude for the way the book gave them closure. Often they would write to say, “I never understood what happened. Finally I do. Thank you for writing this.” It was the last thing I was expecting. And it was really kind of amazing.

BAD ENDS: The best of the worst from Over the Edge and Off the Wall

At Grand Canyon…

Lane McDaniels, 42

June 12, 1928

River Mile 4, Navajo Bridge, Marble Canyon

McDaniels, a construction worker, lost his footing on a scaffold while helping build what qualified, at the time, as the world’s highest steel bridge and fell 470 feet into the Colorado River. No safetynet had been set up, due toconcerns that hot rivets might ignite it. Observers reported that McDaniels’s body appeared to “burst and flatten out” on impact.

United Airlines Flight 718 (58 people aboard); TWA Flight 2 (70 people aboard)

June 30, 1956

Chuar Butte and Temple Butte

TWA’s Super Constellation Flight 2 entered the airspace of United’s DC-7 Flight 718 at 21,000 feet. The pilots of both aircraft had flown off course┬Śperhaps to give passengers a good view of the Canyon. The DC-7 overtook the Super Constellation, and its left wing sliced off the Super Connie’s tail. Both aircraft plunged into the canyon. There were no survivors.

Anthony Krueger, 20

March 25, 1971

Phantom Ranch beach

While camping with friends, Krueger imbibed a brew made from blossoms of the sacred datura plant, a poisonous weed with mind-altering properties. Several hours later, after trying to lift huge boulders, talking to nonexistent people, and eating dirt, he disappeared, apparently attempted to swim the Colorado River, and drowned. Five weeks later, his body was found seven miles downstream.

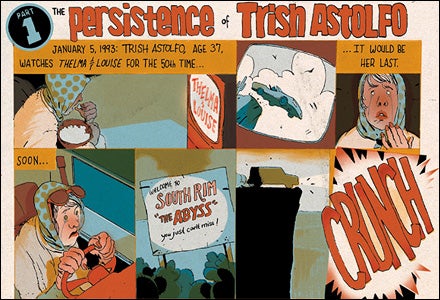

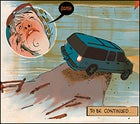

Trish Astolfo, 37

January 5, 1993

The Abyss, South Rim

Astolfo, reportedly inspired by repeated viewings of Thelma & Louise, tried to drive her Chevy Suburban into the Grand Canyon, but the vehicle high-centered before it cleared the rim. She then opened the door, walked to the edge, and leaped off┬Śonly to land on a rocky ledge 20 feet below. Injured but still alive, she crawled to a nearby precipice, dropped over its edge, and fell 150 feet to her death.

Donna Spangler, 59

April 11, 1993

Grandview Trail, in the Redwall below Horseshoe Mesa

Robert Merlin Spangler shoved his wife, Donna, off a cliff to avoid the inconvenience of a divorce. She fell 160 feet. After signing a confession to this and three other murders, Spangler got a life sentence and ended up dying of cancerin prison. He requested a National Park Service permit to have his ashes spread over the Grand Canyon. U.S. District Judge Paul G. Rosenblatt ordered the NPS to deny it.

Matthew J. Garcy, 20

October 24, 1997

Cape Royal

Garcy asked a bystander to take his picture and mail a letter that was sitting on the front seat of his car. He then handed his glasses to the bystander and jumped off the North Rim, falling 400 feet to his death.

BAD ENDS: The best of the worst from Over the Edge and Off the Wall

At Yosemite…

Pomposo Merino, age unknown

July 23, 1883

A sheep camp ten miles above Little Yosemite Valley

Merino, a shepherd from Mexico, was in the midst of telling fellow shepherd Henry Montijo about seeing a man knock away a pistol during a brawl. To demonstrate, he pointed his own loaded pistol at his head and struck it away. The pistol went off, killing Merino.

William L. Gooch, 22

May 19, 1976

Ledge Trail to Glacier Point

Hiking solo, Gooch scrambled down the Ledge Trail, which was officially closed and posted with a sign reading DANGER! DO NOT ATTEMPT TO FOLLOW THIS ABANDONED TRAIL. Shortly after heading out, he detoured off-trail to fill his water bottle and slipped. Witnesses saw him sliding down a wet slab and heard him mutter, “Oh, shit!” as he fatally plunged 600 feet.

Sonia Janet Goldstein, 33; Richard Russell Mughir, 29

August 17, 1985

Glacier Point

At 7:45 a.m., two witnesses saw Goldstein’s body plummeting down the face of Glacier Point. Minutes later, they observed Mughir posing on the ledge with his arms open in a come-to-Jesus posture. According to investigators, who interviewed Mughir’s therapist, the psychologically unstable Mughir apparently had convinced Goldstein, his girlfriend, to join him in a suicide pact in which he stabbed her to death atop Glacier Point, tossed her over the side, then followed by jumping off the precipice himself.

Jan Davis, 58

October 22, 1999

El Capitan

Davis, a professional stuntwoman, jumped off El Cap to protest the National Park Service’s ban on BASE jumping in the park. Davis failed to deploy her chute in time and crashed into Yosemite Valley in front of 150 onlookers.

Vladimir Boutkovski, 24

August 17, 2001

Northwest Face, Half Dome

At 6:30 a.m., three climbers at the base of Half Dome heard a whoosh and saw a man falling in a skydiving position before slamming into the ground headfirst. Boutkovski, a Russian immigrant, had been studying the teachings of Carlos Castaneda. According to a report by an NPS investigator, a subsequent interview with one of Boutkovski’s friends revealed that the young man’s belief in “magic and mysticism” had led him to conclude that the jump would “free him from the bounds of earth.”

Joseph E. Crowe, 25

December 29, 2002

Zodiac route, El Capitan

Crowe was attempting to do a solo winter climb of an 1,800-foot route on El Capitan. Duringa snowstorm, he tried to rappel down, but his rope came up short. He froze to death, just 25 feet from the bottom.