Green Acres

Open Water

Urban waterways for paddling

Detroit, Houston, MilwaukeeÔÇönone of these cities are exactly paddling meccas. But in the past decade, paddle routes have become centerpieces of ┬şurban-restoration projects across the country. Why the surge? Water trails decrease pollution, expand transportation options, andÔÇömost importantÔÇöincrease tourism. North CarolinaÔÇÖs water trails bring in $55 million in revenue each year. Here are four urban waterways helping to revitalize their cities.

Milwaukee Urban Paddle Trail, Milwaukee

A 25-mile stretch of the Milwau┬şkee, Menomonee, and Kinni┬şckin┬şnic rivers passes idled industrial plants, marshes full of egrets, and (key stop) the Rock Bottom Brewery.

Detroit Heritage River Water Trail, Detroit

This route will eventually include 120 miles of paddling on the ┬şDetroit, Huron, Rouge, and Raisin rivers. For now your best bet is Riverside Kayak Connections Canal Tour, a loop beginning at Maheras Gentry Park that highlights the riverÔÇÖs rejuvenation and DetroitÔÇÖs historic canal neighborhood.

Buffalo Bayou Paddle Trail, Houston

A local nonprofit cleaned up HoustonÔÇÖs downtown slough, adding parks and green spaces on-shore. Put in at Woodway Memorial Park for a 7.5-mile evening paddle, and stop at the Waugh Bridge to watch 300,000 Mexican free-tailed bats go berserk.

Congaree River Trail, Columbia, South Carolina

Launch from West Columbia Landing near the Gervais Street Bridge for a four-mile paddle through forested Granby Park. Pack a bag if you intend to pass Cayce LandingÔÇöitÔÇÖs the last take-out for 48 miles, until Congaree National Park, an immense stretch of old-growth hardwood forest.

Market Watch

Local-food distributors

City Farm

Chicago’s City Farm

Chicago’s City FarmIn order for locally grown food to have a true impact on urban sustainability, all those tomatoes and radishes need to move beyond just the NPR tote bags and into grocery stores, school lunches, and inner-city food deserts. The problem is, produce buyers donÔÇÖt have the time to coordinate with a dozen farmers. ThatÔÇÖs why recently launched websites like and are combining social networking and agri┬şculture. Growers list what theyÔÇÖre harvesting, and buyers place orders online and pick them up. Which is good for, say, a tiny bistro, but public schools arenÔÇÖt going to stock their cafeterias from individual farm stands.

The next step? Local distribution centers: farmers send their crops to a modern processing facility, which delivers them to urban stores and restaurants, the same way conventional food finishes its 3,000-mile journey. The SENC Foods Processing and Distribution Center opened in Burgaw, North Carolina, in March; Madison, Wisconsin, and Berkeley, California, have similar projects launching in the next year.

The real game-changer, however, could be a company many consider the antichrist of localism: Walmart. Now the largest grocer in the nation, the big-box retailer has begun selling local produce to reduce shipping costs and reach its sustainability goals. Even more, a new program aims to support growers who reestablish traditional local crops, like blueberries and onions, that have been displaced by cotton, soybeans, and corn.

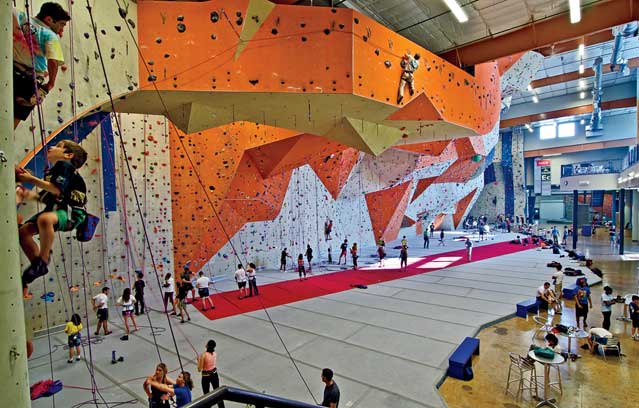

Bigger Walls

Urban climbing gyms

High-end climbing gyms started popping up in New York City and San Francisco in the nineties. But the new surprise hub? Atlanta, home to the countryÔÇÖs largest, the year-old Stone ┬şSummit Climbing and Fitness Center, a 45,000-square-foot facility with 60-foot-tall crags and a bouldering room.

Stone SummitÔÇÖs director of operations, 28-year-old Daniel Luke, realizes that building such a huge space was a gamble, especially in a city with an athletic scene dominated by ball sports. ÔÇťThe climbing culture in Atlanta was not very large, so we were nervous going into this,ÔÇŁ he says. But Stone Summit and other new climbing ┬şcathedrals like San DiegoÔÇÖs Mesa Rim and BoulderÔÇÖs Movement are turning solid profits. Luke estimates that Stone Summit attracts 2,000 novices a month, many of whom eventually spring for a $500 annual membership. LukeÔÇÖs goal? Welcome a new group of climbers and give at least a few rock rats something completely novel: steady employment. ÔÇťOur staff are passionate climbers who can pursue their career at this gym,ÔÇŁ says Luke. ÔÇťThat means a better quality of employee and better customer service.ÔÇŁ

Going Dark

Dark-sky preservation

Between 30 and 50 percent of outdoor lighting is wasted, with $1 billion worth of stray lumens released into the air each year. (Google ÔÇťNASA Earth night┬şlightsÔÇŁ if you donÔÇÖt believe it.) Not only does overlighting obscure the night sky, confuse birds, and add CO2 to the atmo┬şsphere, but recent research has found that it also screws up our circadian rhythms. And until recently, little towns like Davis, California, and Flagstaff, Arizona, were the few bright spots in dark-sky preservation.

ThereÔÇÖs reason to think the big boys will be headed that way soon, though. ItÔÇÖs estimated that in the next few years, LEDs will be 40 percent more ┬şefficient than the 37 million high-┬şpressure sodium lights currently ┬şlining our streets, a savings that will spur a switch. Since LEDs shoot straight, putting light where theyÔÇÖre pointed and not up into the stratosphere, theyÔÇÖre a big part of the ┬şdark-sky equa┬ştion. More ┬şimportant, in June the Tucson, ArizonaÔÇôbased International Dark-Sky Association (IDA) released the Model Lighting Ordinance for urban areas. The plan recommends cities set up lighting zones. Think of it as a muni┬şcipal cap-and-trade system: in New York City, Times Square could keep its brights burning while downtown Brooklyn dims its parking lots, hoods streetlights, and darkens office buildings. The plan hasnÔÇÖt been in circulation long enough for anyone to vote it into law, but IDA director Bob Parks is confident weÔÇÖll see several metropolises going dark soon. ÔÇťFor the past year, IÔÇÖve had cities calling me every few weeks asking if this was ready,ÔÇŁ he says. ÔÇťItÔÇÖs the tool theyÔÇÖve all been waiting for.ÔÇŁ

Smarter Sharing

Bike-sharing programs

These are heady times for fans of two-wheeled transport. Washington, D.C., and Montreal already have popular bike-share programs in place. So do San Antonio and Des Moines, Iowa. Coming soon: New York City, San Francisco, and Chattanooga.

The question is which of these programs will stick and which will turn out to be taxpayer-funded flops. Not surprisingly, it helps to start with a relatively bike-friendly city like Washington, D.C., whose program, Capital Bikeshare, boasted 1,100 bikes and 360,000 trips in its first seven months. The nationÔÇÖs capital, which has expanded its bike lanes from three miles to fifty in the past decade, saw an 80 percent boost in ridership from 2007 to 2010.

ItÔÇÖs a model that Boston and New YorkÔÇötwo cities considered challenging for ┬şbikersÔÇöhave taken note of. Boston launched Hubway, with 600 bikes and 38 miles of lanes, in July, and New York was on track to roll out its program by spring 2012.

But bike shares do have their limiting factors. ThereÔÇÖs the issue of ┬şcapacity. ÔÇťItÔÇÖs all about the docks,ÔÇŁ says ┬şAlison Cohen, president of Alta Bike Share, the company that owns the racking docks in D.C., Boston, and Melbourne, Australia. Finding space downtown to ┬şaccommodate the morning flow is always tough. In New York, critics in tourist-heavy zones like SoHo worry about losing real estate on narrow sidewalks to bike-parking stations.

And then thereÔÇÖs the germ issue: for safety and hygiene reasons, no bike-share program rents helmets. Whereas D.C.ÔÇÖs bikes average five rides per day, notes Cohen, in Melbourne, Australia, they get just one. The primary reason: a ┬şmandatory helmet law. But ┬şCohen feels the market could provide a solution. London-based designer Ani┬ş┬şrudha Rao has already prototyped the Kranium, an inexpensive cardboard helmet that Rao envisions being sold in vending machines at bike-share stations.

The bottom line: make it easy and they will ride.

Tent Cities

Urban campgrounds

On June 29, Gateway National ┬şRecreation Area inaugurated 35 new campsitesÔÇöa totally unremarkable event except that the sites are located at Floyd Bennett Field, a defunct municipal airport in the southeast corner of Brooklyn. By 2013, park officials hope to raise that ┬şnumber to 90 and eventually offer as many as 600 campsites, which cost $20 to $40 per night and can be booked online. And no, this is not a ploy to get the homeless out of Manhattan.

ÔÇťWe want to make New York the leading example of what we can do with urban parks,ÔÇŁ Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar said during a June visit to the site.

If other urban campgrounds around the countryÔÇöincluding Rob Hill in San ┬şFrancisco; Oak Mountain State Park near Birmingham, Alabama; and ┬şGreenbelt Park in the D.C. suburbsÔÇöare anything like Floyd Bennett Field, theyÔÇÖll offer an ice rink, a model-airplane runway, and miniature golf.

And while the concept is easy to poke fun at, the campsites themselves arenÔÇÖt badÔÇöespecially G31, which is tucked away in the foliage. The idea isnÔÇÖt so much to offer an urban wilderness experience as to suggest the existence of wilderness at all.

ÔÇťCampers arenÔÇÖt going to Yellowstone,ÔÇŁ says Jennifer Bethea, a park ranger, ÔÇťbut maybe after camping here they will.ÔÇŁ And thatÔÇÖs just it: if this unlikely getaway can somehow make the inner-city residents who are its most frequent visitors feel more comfortable in their national parks, then itÔÇÖs done its job.

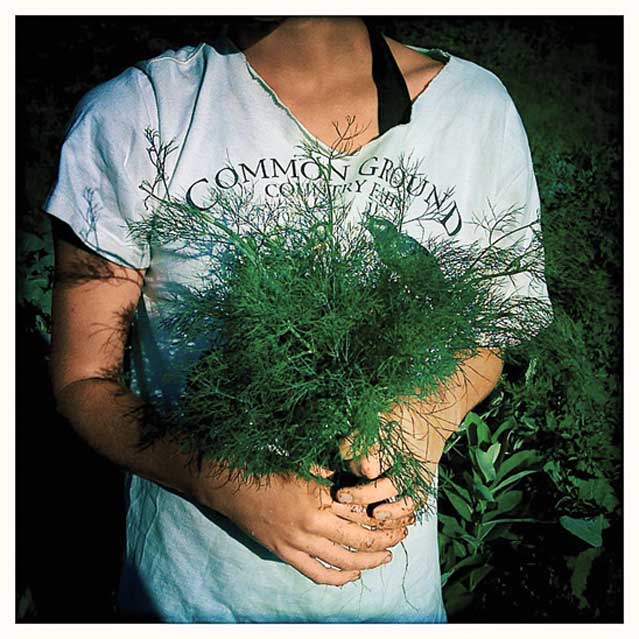

Backyard Livestock

How down on the farm came to mean an empty lot in Berkeley

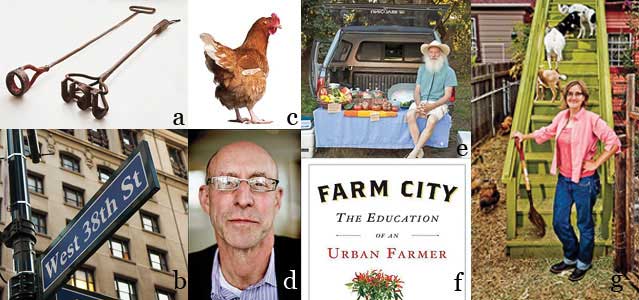

7th Century: Medieval farmers invent the cattle brand. a.

1932: The Underground Cattle Passage is built beneath West 38th Street in New York City to increase the flow to slaughterhouses. b.

1960s: The majority of city slaughterhouses in Manhattan close. Many cities ban backyard hens.

2004: A group in Madison, Wisconsin, forms the Poultry Underground to overturn a ban on domestic birds. The revival is on. c.

2006: Michael Pollan publishes The Omnivore’s Dilemma. d.

2007: The New Oxford American Dictionary designates locavore word of the year. e.

2009: Oakland resident Novella Carpenter’s Farm City is published. In the next year, sales of chicken feed in the city double. f.

2009: Entrepreneur John Hantz pledges $30 million to a complex of urban farms housed in Detroit’s abandoned plots.

2010: The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene rescinds a long-standing ban on honeybees.

March 2011: Oakland shuts down Novella Carpenter’s farm for selling produce without a permit. g.