AT THE ANNUAL WILD GAME DINNER FOR MEN ONLY, outside the Family Life Christian Fellowship, a non-denominational church in Lafayette, Louisiana, Harold Schoeffler, the area’s leading Cadillac dealer, finished his plate of duck gumbo and joined 200 other sportsmen as they crossed the lawn and mounted the wide steps of the white chapel. “Looks like we gonna get a sermon with our bread,” he said to me and his friend Mike Francis, former chairman of the Louisiana Republican party and a prominent success in the state’s oil industry. We sat down in a pew, and I looked around.

With God (and the facts) on his side: Schoeffler at his car dealership in Lafayette, Louisiana

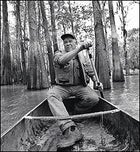

With God (and the facts) on his side: Schoeffler at his car dealership in Lafayette, Louisiana Swamp thing: Schoeffler gets in touch with his paddlin’ self on Lake Martin, a few miles northeast of Lafayette.

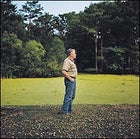

Swamp thing: Schoeffler gets in touch with his paddlin’ self on Lake Martin, a few miles northeast of Lafayette. Schoeffler gazes at the Atchafalaya’s Cove Swamp. “The basin is dying,” he says.

Schoeffler gazes at the Atchafalaya’s Cove Swamp. “The basin is dying,” he says.

The men in attendance ranged from field hands in camo to CEOs in Ralph Lauren; there were Methodists and Baptists and Presbyterians. Schoeffler himself is a devout Catholic who never misses Sunday mass. But what brings them all together each year is a passion for Christ, the outdoors, and the nearby Atchafalaya Basin—at more than 1.1 million acres the largest river-basin swamp in North America, and one of the most biologically productive and diverse areas anywhere in the world. In southern Louisiana, a fierce love of place cuts across lines of class and religion. On the church dais, flanked by a shotgun and a fishing rod, Jim Darnell, a sixtyish itinerant preacher from Texas who also writes spiritual hunting-and-fishing stories, cleared his throat and began by telling on himself—how as a boy he snuck over the top of a levee and blasted away at a flock of blue-winged teal drifting on the river. The birds refused to die, or even fly, because they turned out to be another hunter’s decoys. Then Darnell got serious and talked about the decoys the devil sets in our path.

He preached for another 20 minutes. You could’ve heard a twig snap. He concluded by saying that among the true and good values in life, like family and a day hunting with friends, one of the foremost was preserving the God-given earth. “Because it’s y’all that are really doing it, the hunters and fishermen. It’s not the pita eaters!”

Schoeffler blew out his breath. “Oh, man,” he murmured, rolling his eyes. Clad in loafers, khakis, and a short-sleeved button-down shirt, the tan, five-foot-eleven Schoeffler, 63, fit right in with the crowd of men gathered here today. But the pita eaters are Harold’s friends, too. Schoeffler can make you a great deal on a new Seville, in a state where Cadillac is still king, but he’s got another, surprising side. He’s chairman of the local chapter of the Sierra Club and one of the most dogged environmentalists in Louisiana. Schoeffler hosts a gloves-off local television show called Eco-Logic, which deals with everything from industrial toxic waste to marshland water levels, and across Louisiana he’s known for repeatedly challenging Big Oil and other industries in fights to protect the basin and the coastal waters of the Gulf of Mexico. For close to a century the Atchafalaya has been a battleground for competing interests—timber, oil, fishing, hunting, water-flow manipulation—which have threatened its survival. Among the champions of the swamp, Schoeffler is a legend.

“He’s a contradiction,” says Bruce Schultz, the Acadian Bureau Chief for the Baton Rouge Advocate. “On some issues he’s the only person who’ll speak out. One day he might be critical of the oil business, and the next day he might invite some of the same people to go duck hunting, or have them over to his house to eat.”

Dailey Berard, president and CEO of Unifab International, a large fabricator of heavy marine oil-drilling equipment, has been battling Schoeffler for three decades. “Tell everyone I love Harold,” he says. “It’s his stupidity and ignorance that drive me crazy!”

Bruce Hamilton, national conservation director for the Sierra Club, puts it succinctly: “Harold’s one of my heroes.” That’s high praise for a man who occasionally raised pocket money while attending the University of Louisiana by poaching alligators in the Audubon Wildlife Reserve.

After dinner and the sermon, Schoeffler and I climbed into his GMC Yukon—he hauls too many boat trailers and too much fish bait to drive a Caddie—and headed out to Lake Fausse Pointe to check his string of crawfish traps. En route, on an arrow-straight road that cut through cane fields and dropped into oak bottom, I asked him how he felt about the “pita eater” comment. Schoeffler laughed. He pointed to a flock of ibis shearing down over the trees.

“I kinda chuckle,” he said, “when I hear the compliment that the hook-and-bullet guys have made a critical contribution to conservation issues. When I look at the major battles that have impacted habitat, endangered species, water quality—it wasn’t them.” I glanced at the three loose shotgun shells on the front seat and the flat-hulled, fatigue-green johnboat on the trailer behind us and thought, This is going to be an interesting week.

SCHOEFFLER IS NOTHING if not connected. His first cousin married one of Louisiana’s U.S. senators, Democrat John Breaux. It amuses him that his wife, Sarah, and Louisiana governor Mike Foster, a Republican, share royalties from oil wells on adjacent properties that their fathers owned. He can communicate just as easily with crawfishermen and oil executives, bridging communities normally thought of as unbridgeable. Some of his victories have changed the way entire industries operate in Louisiana. In the 1980s he helped launch a series of lawsuits against a century-old shell-dredging industry that was devastating the shell-bottom habitats of the Gulf Coast in order to provide the signature crunch of driveways from Texas to Florida. Employing ingenious legal tactics to sue the state of Louisiana over the issuing of permits to the dredgers, Schoeffler led a fight that eventually shut down the four big dredging companies and the last shell dredger in the gulf. In 1987, he petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to have the Louisiana black bear placed on the endangered species list. This set in motion a series of events that led him into a controversial 1991 lawsuit (with backing from Defenders of Wildlife and the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund, which is now called Earthjustice) against Fish and Wildlife to have the bear listed as a threatened species.

“Hell, man,” Schoeffler told me, his voice rising with astonishment at the prevailing dumbassedness of the time, “there were at best guess less than 300 bears left in the whole state. The Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries was issuing tens of thousands of big-game permits. What you gonna do, sit around and debate protection strategies while the last bear is turned into a rug?” (In the 1987-1988 hunting season, the department issued 178,479 big-game hunting permits.)

The case was settled, which resulted in the Louisiana black bear being listed as threatened, and even critics of Schoeffler’s approach concede that most of the positive conservation gains for the bear that are in place today, including establishment of the 9,028-acre Bayou Teche National Wildlife Refuge, are a result of his tenacity. Schoeffler was also an enthusiastic supporter of a series of successful Clean Water Act lawsuits filed by the Sierra Club against dischargers of “produced water” in Texas and Louisiana. This toxic benzene- and salt-loaded waste was traditionally being dumped from oil wells directly into wetlands. But as a result of these suits, since the mid-1990s, in the Environmental Protection Agency’s Region 6 (which includes all of Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico), the practice has been replaced by pumping produced water “down-hole”—back into an old well deep underground.

All the fights Schoeffler has taken on over the past quarter-century have had one basic aim: to preserve Louisiana’s swamps and marshes and coastline for future generations to enjoy the way he and his four brothers and three sisters did growing up. Currently, he’s involved in several regional battles that may affect public access and the amount of pollution allowed in waterways across the nation. Last year, the Sierra Club’s statewide Louisiana Delta Chapter—of which he is conservation chair—scored a major victory against EPA Region 6 that requires a ten-year cleanup of most of Louisiana’s waterways. Schoeffler is now a key player in meetings with the counsel of the EPA to work out timetables and water-quality parameters.

And, collaborating with local pro bono lawyers, he was the named plaintiff in a complex suit filed in 2001 in St. Martin Parish District Court. Joined by Cajun crawfishermen, Schoeffler is demanding clear legal boundaries in the Atchafalaya Basin. Much of the land in dispute is underwater most of the year and may be subject to a tangle of laws regulating commerce on navigable waterways and public use of riverbanks. According to Schoeffler, huge private landowners are trying to chain the fishermen out of bayous their families have fished for generations, with access given only if they buy expensive permits. In late May, the district court judge ruled against Schoeffler, but, as always, he remains undeterred.

“We’re very optimistic,” he says exuberantly. “It’s put the landowners in an awful tight spot—if they refuse to give us a boundary, then where are they in terms of arresting anyone for trespassing?” He plans to appeal the case and remains convinced that this fight will shake up how fishery, mineral, and even oil revenues are apportioned in a swampland larger than Rhode Island, and may serve as a model for similar disputes nationwide.

ONE MORNING, Schoeffler and I arrived at Schoeffler Cadillac before eight. It’s a compact dealership on the east side of Lafayette, squared off against a Mercedes/BMW lot across the street. In the large, clean-swept repair shop, Schoeffler poured coffee into a plastic cup. His hand shook as he brought it to his mouth, a slight tremor he’s had since he was a kid. He stood with three mechanics, all of whom had Cajun accents. One said, “Hey, Mr. Harold, I saw you on the TV last night. You think they gonna make us buy a extra license to put a trap down in the bayou?” He was talking about the boundary case.

Harold drained the cup and threw it in a steel bin. “They gonna squeeze you every way they can,” he said. “They deputizing fools right now to arrest fishermen. I told ’em, ‘Y’all arresting people on property you don’t own.'”

He went to his office and sat behind his cluttered desk, facing the polished, speckled floor of the showroom. A huge trophy buck stared ruefully down from the wall at the World Wildlife Fund and Sierra Club stickers on the filing cabinet. Schoeffler picked up the phone and sold two used cars to area dealers. Then he and I went out to deliver a new Cadillac CTS to a customer on the other side of town. When we returned to his office, he called the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers at district headquarters, in New Orleans, and hounded four different offices for water-level data from their gauge at Butte La Rose, in the basin. All this before 10 a.m. Schoeffler grew up in Lafayette. His mother was a local Cajun, descended from French “Acadian” stock driven from eastern Canada by the British in the late 18th century. His father was a German blacksmith who immigrated to the U.S. in 1910, first worked for the Southern Pacific Railroad, and then started an auto repair shop that evolved into Schoeffler Cadillac. Paul Schoeffler imparted to his five sons an almost religious passion for hunting and fishing. Harold grew up in awe of the power and beauty of the cypress swamps and islanded coast, seeing nature as the purest evidence of God’s love for man.

“When I was a boy, we used to fish the west side of Vermilion Bay,” he said. “There was a circular shell bank—must have been 200 acres across the top, at normal tide about two to three feet deep, all white clam shells—” The phone rang.

“Just a minute,” he said. “How y’all doin’?” he called into the phone. “Oh, we makin’ it. Had a good day Saturday out by Teal Island. Shot our limit in half an hour. OK. I’ll bring it over this morning.” He hung up. “That was the president of a drilling company. He just bought one of our new DeVilles. Where was I? The Cocshin shell bank. I was a boy. You could jump out of the boat and wade around in a circle, fishing off the side. It was fabulous fishing—we caught redfish, speckled trout, flounder. The speckled trout hit a bait like a freight train.

“I remember one beautiful August morning, about 1950—we got out there to the usual place and there were two of those big-ass dredges and nine or ten barges, and the reef was gone. It was sitting on those barges. We cried. What they were doing was wrong. I realized some years later that it was the biggest insult to water quality in the state of Louisiana.”

The tragedy of the reef stuck with Schoeffler and worked on him slowly, like a grain of grit inside an oyster. He attended the Catholic, all-boys Cathedral High School and later the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, where he graduated in 1961 with a degree in business management and economics. That same year he married Mary Anne Mehaffey and entered the Air Force for a four-year stint as a supply officer.

The outdoors was never far from his thoughts. In 1963, at Robins Air Force Base, in Georgia, he became president of the largest rod-and-gun club in the state. “We were always dealing with conservation issues,” Schoeffler said. In 1965 he returned to Lafayette and entered the family business. By then he had two young children, and his marriage soon ended. He later got involved with the Sierra Club’s Acadian Group (which covers the southwestern corner of Louisiana) by leading canoe trips, and by the late seventies had become its chairman. Along the way, he met his second wife, Sarah Todd, with whom he had four more children.

One day in 1979 he walked down to Vermilion Bayou, which runs behind his graceful salvaged-cypress house in Lafayette. The river was covered with a sheen of oil. Schoeffler realized he had to do something. Now. The oil from every crankcase in town was ending up in the bayou. Only his dealership and one other, he says, recycled oil. He went to the library and dug out a little-known city fire ordinance that prohibited the dumping of volatile material into storm drains. Schoeffler brought the ordinance and the situation to the attention of the city fire marshal. “Within two months,” Schoeffler says, “the bayou was cleaned up. All the stations were recycling their oil. Now you have the somewhat unique situation in which the fire marshal is enforcing environmental protection. He was afraid the damn sewer lines would explode!”

Schoeffler fishes out in the gulf at least once a week. He tends to his string of crab and crawfish traps. He also leads a local Boy Scout troop. But it’s the environmental battles that are always on his mind. The sheer glee with which Schoeffler attacks these issues, and his unflagging commitment, make him a formidable adversary. His basic strategy is this: Know precisely who the enemy is, and know the facts, because 90 percent of them are on your side. God is, too.

Doing his homework has made Schoeffler a go-to guy in Louisiana environmental politics. Last year, when CNN wanted to do a story about oil drilling in national wildlife reserves, southern style, they enlisted Schoeffler. “John Breaux had made the statement that we do it so well in Louisiana, we can do it in the Arctic,” Schoeffler says. He took CNN to southern Louisiana’s Lacassine National Wildlife Refuge, where the marsh hydrology is similar to that of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and about 60 percent of the land is open to drilling. Where there was oil production, the land was dead. “It was so obvious,” he says. “You literally couldn’t find a lotus in the oil patch. Then we went into the wilderness zone, and the lilies and cattails and irises were everywhere.”

The storm of activity and repository of knowledge that is Schoeffler makes him a universally respected, if equivocal, figure in the eyes of the community. Go to a Sunday brunch with him at Dwyer’s, one of the best restaurants in Lafayette, and you can hardly eat for the stream of folks from the country club set who stop by the table to give him their regards.

Others are less polite. Dailey Berard, the fabricator of heavy marine oil-drilling equipment, said with unabashed vehemence, “The bubble in that man’s head is not level. He’s got a right to be wrong for 30 years.”

“Do you drive a Cadillac?” I asked Berard.

“No! My wife does, from Schoeffler, which irritates me no end. I drive a Lincoln for spite.”

Then he admitted that he and Schoeffler sometimes head off to eat dinner together after a contentious public meeting.

SCHOEFFLER AND I DROVE over the grass hump of a levee one afternoon, put a canoe in at a small concrete landing called Meyette Point, and began floating down the Atchafalaya River. The autumn sun hammered down, and we slipped along in silence, bent to the paddles.

The Atchafalaya takes 30 percent of the combined flow of the Red River and the Mississippi and feeds it into a system of lakes and ever-smaller bayous that spread like capillaries into swamp and marsh wetlands. Even with runoff from 31 states and two Canadian provinces pouring into this sponge, the wide river was low at its densely jungled banks, the current brown and barely perceptible. We paddled steadily into a maze of blackwater channels, turning into Bayou Boudie at dusk. Schoeffler had stroked powerfully, without letup, all afternoon. I was beat. He rested his paddle, and we drifted into a tight bend choked with mats of floating hyacinth. The canoe whispered into the lilies and stopped. All around us, the massive, bell-shaped trunks of the cypress trees spread into a lacework canopy trailing veils of Spanish moss. From every quarter throbbed peepers and katydids and locusts. A great blue heron ghosted out of the trees, stately and slow. There wasn’t a speck of dry ground anywhere.

“The basin is dying,” Schoeffler said.

You could’ve fooled me. Smack in the path of the Mississippi Flyway, it supports half of America’s migratory waterfowl. It is home to 300 species of birds, including 26,000 nesting pairs of herons, egrets, and ibises. Fish yields have exceeded a fantastic 1,000 pounds per acre.

One of the problems is that all this takes place between two roughly parallel earthen levees, 15 miles apart. The entire basin as it exists today is a giant spillway designed to drain off the raging Mississippi in case of a “project flood,” Army Corps-ese for all hell breaking loose. The idea is to shunt the water down the Atchafalaya and save New Orleans, one of the most vulnerable potential disaster areas in the country. When that’s not happening, the massive Old River Control Complex—basically a series of gates—regulates the amount of water that flows from the Mississippi into the Atchafalaya. Schoeffler and others believe the basin isn’t getting nearly enough water and is stagnating.

“It’s silting in,” Schoeffler said. “The 1954 Flood Control Act, a federal law that controls the division between the Mississippi and the Atchafalaya, was deeded to keep the Atchafalaya mid- to full-bank. There was enough flow to scour out and maintain the channels in the lower river so that when the flood comes it can handle it. But the Corps isn’t giving the basin enough water.

“We have attorneys working on a federal lawsuit that will challenge the Corps’s failure to comply with certain environmental protection regulations,” Schoeffler continued. “Last May and June, there was dead water everywhere—dead crawfish and dead fish and dead oysters from Cameron Parish to Terrebone Parish. It’s a threat to water quality, to the fisheries, and to public safety.”

The mosquitoes thickened around us. I turned on my headlamp and saw pairs of shiny red eyes like rows of tiny taillights all along the edge of the hyacinths.

“Those are alligators, huh?” I said.

“You bet,” said Harold.

“Um, where are we going to camp?”

“Camp?” He laughed. “Man, we’re just getting warmed up.”

We paddled until 2 a.m.

THE NEXT EVENING at sunset, we barreled down a black-tar road between fields of tall sugarcane in Schoeffler’s truck. We were heading to Catahoula, on the edge of the basin, to a meeting of the Cajun crawfishermen, fellow plaintiffs in Schoeffler’s lawsuit against big landowners.

The men are fighting for the survival of a way of life that’s been handed down from generation to generation since the 1800s: making a living fishing crawfish and crabs out of small boats in the maze of the swamp. With less and less water being diverted into the Atchafalaya, they are battling effects of the basin’s stagnation and degraded water quality, as well as access issues that are addressed in the lawsuit.

We pulled off the state road onto a dark lane lined with small houses. Twenty pickups nosed up to a clapboard camp. Harold opened the door of the cabin and let out a gust of accented voices and the smells of a fais do do, a Cajun party. Inside, 30 men and a few women sat at two long tables littered with pop cans and bottles of hot sauce and paper plates piled with fried soft-shell crabs and crawfish étouffée. The men wore overalls, jeans, and baseball caps, and many had cell phones clipped to their belts. “Oh, hey, Mr. Harold,” said Mike Bienvenu, president of the western branch of the Louisiana Crawfish Producers Association. “We was just discussing the boundary case.” Jody Meche, a 34-year-old fisherman, stood up. “They want the big sell of the Cajun way of life,” he said, pushing back his cap. “Keep the Cajun music alive, keep the French speaking going. All that. But they don’t want us to have the freedom to exercise and practice our heritage, fish the way our fathers fished. We’re not in a celebrating mood anymore.”

Schoeffler leaned over to me. His hand quavered as he set down a can of Dr Pepper. “Man,” he said, “that’s a bunch that’s gonna be tough to reckon with. They’ve learned how to access the press, they’ve learned about the law, and they’re a little angry about everything.” Schoeffler was happy. Democracy was in fine fettle. A Goliath was lumbering toward his destiny. Less than a mile away, on the other side of an earthen levee, the ancient basin pulsed and hooted and sang in the dark.