FLYING ATLANTA to San Francisco to catch the Braves vs. the Giants on the waterfront tonight, I anticipate a reaction as I exit the first-class lavatory wearing a wetsuit. My unsavory, knife-fight-in-a-phone-booth noises couldn’t have gone unnoticed.

San Francisco

A batting-practice splash hit by Bonds

A batting-practice splash hit by BondsSan Francisco

The view from downtown

The view from downtownSan Francisco

A couple cold ones

A couple cold onesWrong. Not a glance from the flight crew.

Maybe it’s because I layered baggy clothing over rubber and look only vaguely reptilian. More likely, though, it’s because our flight is three hours late, due to a “major medical emergency” involving drip bags, oxygen, and a gurney for the unfortunate man sitting behind me.

So it goes. My plan was to be floating in McCovey Cove, over the right-field wall of AT&T Park, by first pitch in case San Francisco’s Barry Bonds splashes home run number 754┬Śand possibly 755 and 756┬Śinto the Bay. Unfortunately, the game is already under way by the time I find a driver willing to trust a man in a wetsuit. But I’m not worried. Tourists use itineraries to see and do what they want. Travelers use itineraries to wipe up the mess when the kimchee hits the fan.

Sometimes, momentum takes an ugly turn, especially when a trip┬Śthis trip, for instance┬Śhas been fine-tuned and all stars seem aligned. Offered for your consideration are these Twilight Zone intersectings:

1. It’s July 24, Barry Lamar Bonds’s birthday. He’s 43, and with 753 career home runs, he’s only two shy of tying the record established on July 20, 1976, by former Braves great Hank Aaron. And, after a slump, Bonds has a hot bat: Last week, he homered twice against the Chicago Cubs.

2. The commissioner of Major League Baseball, Bud Selig, is in attendance after conspicuously avoiding earlier Giants games, perhaps because of the BALCO steroids investigation┬Śand maybe because Hammerin’ Hank is his close friend.

3. Atlanta’s starting pitcher is Tim Hudson. A few years back, he couldn’t find a competent catcher while visiting his Florida in-laws, so he had to settle for me, an over-the-hill amateur who still plays the game┬Śhardball, not softball. The man was unfailingly patient while I ran down the ball and threw it back. We’ve been friends ever since.

4. ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°, also celebrating an anniversary, called out of the blue and asked me to participate in the homer-hunting lunacy of McCovey Cove, unaware that it was Bonds’s birthday; that Hudson was pitching; that I’d caught Hudson; that the guy behind me would stroke out (but live) and my plane would be three hours late; and that I am sufficiently greedy to change, Clark Kent style, in a plane lavatory just on the outside chance I can swim my way to riches by chasing yet another Tim Hudson fastball.

What are the odds?

I CALL AN OLD FRIEND of mine, legendary Red Sox pitcher Bill “Spaceman” Lee, while listening to the game on the radio as my limo stops for red lights, traffic cops, old ladies in wheelchairs┬Śany excuse to use the brakes. It’s the top of the fourth. Not only has Tim been overpowering on the mound; he just singled up the middle: Braves 3, Giants 0.

“Wind’s blowing out, but still I think Bonds is screwed,” Bill says from his Vermont farm. “Hudson’s got a great sinker tonight, and he’s gutsy.” Earlier, I asked Bill to advise me, inning by inning, where to position my kayak when Bonds comes to the plate. Though frequently caricatured as a left-leaning pot legalizer, Spaceman is a brilliant, tireless student of philosophy, weather, and spinning round objects.

“But where should I be?” I ask.

“In center field, drinking beer,” he suggests. “But if you’re wearing a wetsuit, don’t go anywhere near the acidheads. They’ll think a giant frog is swallowing a bald guy.”

Not helpful. Nor was the phone message I received today from Gene Lamont, third-base coach for Detroit and American League manager of the year with the White Sox in 1993: “Randy, it’s Geno. I doubt if Bonds will go long, but if he does, just hope the ball doesn’t hit you in the hands. Someone could get hurt when you drop it.”

Funny.

Secretly, though, I suspect Gene’s right. Tim’s classy and laid-back off the field, but he’s pure Alabama hardass on the mound. “I don’t nibble around the outside corner, and Barry knows it,” he told me yesterday. “I go right at him with fastballs┬Śsinkers and cutters.”

Later, he’ll tell me that veteran Atlanta third baseman Chipper Jones made it clear to the Braves pitchers that they’d better bring their game faces to San Francisco.

“Chipper was razzing us, asking who was going to live in infamy by giving one up to Bonds┬Śyou know, kidding but not really kidding. Some guys might think it’s cool to get their name in the record books that way, but it is definitely not cool.”

So it wasn’t going to be an easy night for the Giants’ slugger.

Still, as I hit the waterfront and get my rented kayak rigged and ready, I imagine the looks on the faces of my baseball buddies if I were to call them and say, “One of us just caught a $500,000 baseball. Check your hands.”

It could happen.

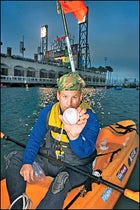

BY THE SEVENTH INNING, I’m sitting in an open kayak┬Ścold, cold San Francisco Bay beneath me, 20-knot winds on the water, the glow of stadium lights above┬Śwhen Bonds strikes out looking on a nasty Tim Hudson fastball.

I pump my fist and say, “Yeah,” then I see the expression on the face of the guy on the surfboard next to me.

“Are you nuts?” he asks.

“Geez, maybe. Gimme a second.”

Valid question. According to memorabilia freaks, Bonds’s 756th home-run ball may fetch up to a cool million. Number 755 could bring as much as half that, and even 754 could sell for ten grand or so.

But, regardless, in McCovey Cove you’d need some kind of Freudian micrometer to determine sanity. There are 14 of us out here, not counting the police boat anchored off the NO WAKE quadrant, which constitutes a fictional sea upon which sails the Bonds Navy, a quasi-fictional armada of regulars who show up whenever the Giants play, day or night. There are ten kayaks, two surfboards, a folding duck boat, and some kind of raft containing what may be a potted fern and a guy in a Giants uniform.

There are a few pretenders, but bona fide flotilla members are easy to spot because of the BONDS NAVY pennants and Giants-orange paint jobs. I’m surprised to discover they’re a convivial group, friendly even to strangers, despite the cove’s reputation as having the toughest lineup this side of Pipeline, the value of the baseballs we’re all jockeying to salvage, and the fact that one of the pretenders (me) is wearing a catcher’s mask.

“Safety first,” I explain.

Not necessary, I’m told.

“Up in the stands, they fight like gladiators over a ball,” says Gene Pointer, a union sign hanger from Petaluma, “but here in the cove it’s pretty laid back. We’re competitive, sure. But we respect each other, too. It takes a special sort of person to do what we’re doing.”

No argument. It’s 59 degrees; water’s 58.

As the game progresses, and as I meet other members of the Bonds Navy, I realize there’s both a loosely structured order to the apparent chaos and a sort of cowboy code of honor.

Home-run balls that land in the cove are called “splash hits.” If a dinger caroms off the quay, it’s not officially a splash hit (although it’s still worth bucks if Bonds hits it), nor is it officially counted as a splash hit if a non-Giant knocks it out of the park.

Pointer, a.k.a. Kayak Man, has five Bonds splash hits to his credit. On Kayak-Man.com, you learn he’s available for “movies, commercials . . . and charity fundraiser events.” His hobbies include surfing and “good times on the high seas.”

Gary Faselli, a retired Stockton cop who retrieved Bonds home run 738 about three months back, makes the pennants. As a member in good standing, he has a lot of say in who gets commissioned.

“You only get the flag if you’ve been out here several years,” he explains. “You’ve got to come to a lot of games.”

Other regulars include Dave “the Spearfisherman” Edlund, a former HP exec who a few years ago retired at age 45 to chase baseballs. There’s Martin Wong, the group’s unofficial photographer. Out here on his surfboard is Patrick Whelly, wearing shades and looking cool despite the cold. Steve Jackson and Tom Hoynes were among the very first “splash dippers,” zooming after balls in their Zodiacs before authorities closed the area to motors.

“It was pretty hairy,” recalls Kayak Man, who used a surfboard then. “They’re good guys, but, man, those propellers are sharp.”

The most famous member of the Bonds Navy is Larry Ellison┬Śnot the billionaire founder of Oracle but a 56-year-old salesman who deals in recovery software. Ellison is also very good at scooping balls┬Śso good, in fact, he’s been dubbed the King of the Cove by the media. On consecutive days, he nabbed Bonds homers 660 (Willie Mays’s career total) and 661. The latter he sold for $17,000, some of which he used to buy a custom-made, computer-equipped Kevlar kayak with a baseball sunk in the hull as if embedded there by Bonds. It’s the fastest boat on the cove, according to regulars. Instead of selling 660, he gave it to Bonds, he says, out of gratitude for what he’s done for the team.

Because it is Bonds’s birthday, Ellison has brought along a chocolate cake, a frosted replica of the stadium. Happy birthday, Barry. I take off my catcher’s mask long enough to try a piece. Delicious.

BY THE BOTTOM OF THE NINTH, it’s Braves 4, Giants 0. Tim Hudson is pitching a shutout gem, but his control isn’t quite as sharp. He walks the lead-off hitter, Omar Vizquel, then Randy Winn.(The game will go 13 innings and end 7-5, Braves.)

I’m dialing Spaceman for advice again as the PA system booms, “Now batting . . . number 25 . . . BARRY BONDS!”

The stadium is packed, and the seismic vibration of umpteen thousand screaming fans is transmitted via water through my frozen butt┬Śkind of a tingly sensation.

Spaceman answers the phone. Talking fast, I tell him, “The wind’s still blowing out, but it’s swung west, right to left.”

“For God’s sake, hug the foul line!” he says. “Hudson’s been killing him all night with that sinker.” Because of the stadium noise, I can barely hear Bill add “Drink two rums and call me in the morning” before he hangs up.

Seconds later, I’m paddling hard toward the right-field foul line, into a wind that could push a foul ball fair. I’m the only boat in the area as I cling to a buoy. This is it, I realize: one of those rare moments with sufficient intersectings to qualify as baseball legend. No outs, bottom of the ninth, tying run on deck, and the soon-to-be most successful home-run hitter in history at the plate┬Śon his birthday.

The stadium quiets for a beat as fans take a tribal breath, waiting for Tim, working from the stretch, to kick and deliver. Umpteen thousand people, including my McCovey Cove kindred, want it to happen. Number 754.

I also realize this: I don’t want it to happen.

It’s not because I dislike Barry Bonds. It’s not because of the steroid controversy. Hell, for a season of old man’s baseball, I used the same over-the-counter stuff Mark McGwire used┬Śhit .240 and looked like someone had goosed me with an air hose. Bonds is an athlete. If I thought pills could give me one day playing major-league ball, I’d let someone shoot them down my throat with a damn slingshot.

No, the reason I don’t want it to happen is Tim Hudson. He, too, is an athlete. His senior year at Auburn, he was first-team All-American as a pitcher and utility player┬Śhit .396 and struck out 165 batters. With Oakland, he was named a Sporting News Rookie Pitcher of the Year in 1999 and was runner-up for the Cy Young Award in 2000. But the man isn’t just a pitcher, he’s a baseball player┬Śa rarity in this age of specialization.

There’s another reason I don’t want Bonds to homer: I’m a catcher┬Śnever gifted, but I love the game and the position. I like the way the bars of a mask frame the world, tunneling vision so all that exists are the pitcher’s eyes and the spinning trajectory of the ball. There’s an energized dynamic between the mound and home plate, a flowing communication, both linear and intuitive, and a circuit that is completed over and over again through the orbiting exchange of a baseball. I’m a catcher, not a water spaniel┬Śa receiver, not a retriever┬Śand although my attachment to the game may be fanciful, it is an orbit I choose not to break.

In past off-seasons, when I caught Tim, he’d say, “I just want to get loose,” so we’d head to the only ball field on the island where his in-laws live. We’d play long toss for 15 minutes, then he’d take the mound and throw 25 to 35 fastballs┬Śfastballs with freakish movement, tailing as they sank. Once, we took my fishing skiff to nearby Useppa Island and worked out on shell middens built by contemporaries of the Maya, the baseball tracing the flight of ancient arrows.

Good mojo.

Tim’s a little taller than me, weighs 30 pounds less, yet when he touches a baseball, there’s the illusion of some elemental transfer of power between the animate and inanimate. It’s as if, through a blessing at birth, his right hand is a conductor in some mystical, kinetic process by which the ball is infused with energy, and so it seems to glow with a voltaic, accelerating force when it jumps from his fingers.

Not true when I toss the ball back. When I throw, gravity reasserts itself and the ball is smothered by friction, its arc collapsing as if a parachute has been pulled. “Put a little color in that rainbow” is a clich├ę I’ve heard too many times.

But a baseball has energy, as Spaceman says.

On this night, freezing and afloat in McCovey Cove, I’m grinning: Hudson jams San Francisco’s man with another nasty fastball, and Bonds pops a weak fly to third. I pump my fist. Yeah.