“Zoe keeps poking me with a stick,” Maddy complained, dodging around the parking lot near the Appalachian Trail sign.

Rubber-Stamping It

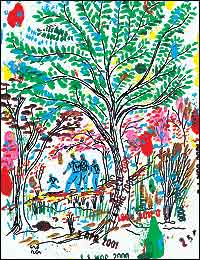

While you won’t need much equipment beyond a compass, a good map, a basic notebook, and a signature rubber stamp, you’ll find a variety of letterboxing and stamp-making supplies at . Illustration by Brian Cronin

Illustration by Brian Cronin

After two hours in the car, we were at our worst. Zoe, 14, and Maddy, six, were driving each other crazy, my wife, Barbara, was impatient, and I had turned into the tyrant father. We had come to do letterboxing, damn it, and letterboxing we would do.

An outdoor activity that originated in England in the late 1800s, letterboxing is part orienteering, part treasure hunt. It has grown geometrically since it was introduced in the United States in its current form just five years ago. Here’s how it works: One player goes to an area suitable for a fine hike—usually on public land—and hides a waterproof box containing a notebook, an ink pad, and a rubber stamp designed for that site. He or she then comes up with clues (sometimes clear, sometimes cryptic) describing the whereabouts of the stash and shares them with other players, usually by posting them on the Letterboxing North America Web site, .

Checking the southern Vermont page of the site, I’d noticed that three letterboxes had been hidden in the shadow of Killington Peak, all within a couple miles of Maine Junction, where the Appalachian Trail heads northeast toward Maine and the Long Trail north toward Canada. All were marked “Clues: Easy” and “Terrain: Moderate”—ideal for the members of our tennis/cricket/yoga/soccer family, who regard hiking as a form of punishment. I printed out the clues, we drove down from our home in northern Vermont, and now, as I stuffed my pockets with the compass and our signature stamps (bought, not homemade—a sure sign of our novice status), I was determined to scoop all three.

We headed purposefully into the woods, Maddy using her hiking stick as if poling a gondola. It was a hard mile uphill, and even the thrill of the treasure hunt was beginning to pall when Zoe let out a whoop that echoed through the forest. She had found the trail junction.

When we caught up with her, we were in for a shock: a hunter crouched by the trail, his rifle erect. Three more soon appeared from the trees, and one pointed out helpfully that Zoe’s faux-sheepskin coat made her look like a deer. By letterboxing standards, this was a bit extreme. Insects and poison ivy are regarded as natural hazards of the sport; being shot at is not.

Trying to pretend the hunters weren’t there, I read the clue aloud: Choose one trail, note its compass bearing, and proceed the same number of paces down the trail. There, we would see a pair of yellow birches to the right, their roots entwined. Under roots and rock, we’d find the box.

We tried the right-hand trail, at 80 degrees. After 80 paces we found ten thousand birches, many of them entwined, many on rocks, none of them over boxes. A certain amount of head scratching, rock turning, and cursing under the breath are to be expected, but the sun was sinking and the air cooling appreciably. We read the instructions for the seventieth time and realized that we were at a junction all right, but it was not Maine Junction. The trail, and the junction, had been moved. Forget about getting all three boxes; we’d be lucky to find one.

It was only the challenge that kept us going. With Zoe and her coat sandwiched between Barbara and me, we strode around Deer Leap Mountain, loudly singing English nonsense songs from my father’s days in the Boy Scouts. We stopped to look at distant ponds, odd insects, vast fungi, and strange, asbestoslike fibers that were growing on a dead branch. This is the real appeal of letterboxing: It gets people outdoors who otherwise would be playing Final Fantasy or watching the Cartoon Network. At last we reached Maine Junction. I took bearings: The birches were either ten to 20 paces down the Long Trail or 80 to 90 down the Appalachian. Barbara and the girls rooted around the LT; I followed the AT out of sight. I’d just found a pair of giant birches, their roots entwined over a hollow big enough to hold an entire post office, when I heard faint voices calling jubilantly through the trees. Barbara had found the box.

It was between a pair of slim birches, among the crisp fallen leaves, hidden under a single stone—just where it was supposed to be, in fact. Inside the small plastic lunchbox, protected by a plastic bag, was a notebook containing twenty or so stamp imprints, some crude, one an astonishingly beautiful, intricate cockerel; a small ink pad; and the Maine Junction stamp—an L pointing west and an A pointing east. Ecstatic, we stamped in—a zebra, a jug, a frame of film, a skateboard—and signed our names. The girls stamped their own notebooks with the Maine Junction stamp.

Suddenly we weren’t tired any more. After all, a puzzle solved at home is a puzzle solved; a puzzle collectively solved in darkening woods is a family triumph. We sang almost all the way back to the car.