Don’t worry about the sharks. They’re large, yes, but they’re sand-tigers, which are relatively docile compared to other species in the water. It’s the barracudas you might consider. From where I’m standing, on the edge of a light tower in the middle of the ocean, I can see dozens of them floating around the structure, waiting for a snack.

“They have a mouthful of K-9-like incisors. Creepy fish,” says Dave Wood, one of the owners of the off the coast of Wilmington, North Carolina. “They typically leave people alone, but don’t wear anything shiny into the water. It gets them going.”

Not that I’m planning on falling in, but when you’re 32 miles out in the middle of the ocean, perched on top of a 60-year-old light tower, watching a bunch of predators swimming below, you wonder.

This is definitely the most adventurous and remote place I’ve ever stayed.

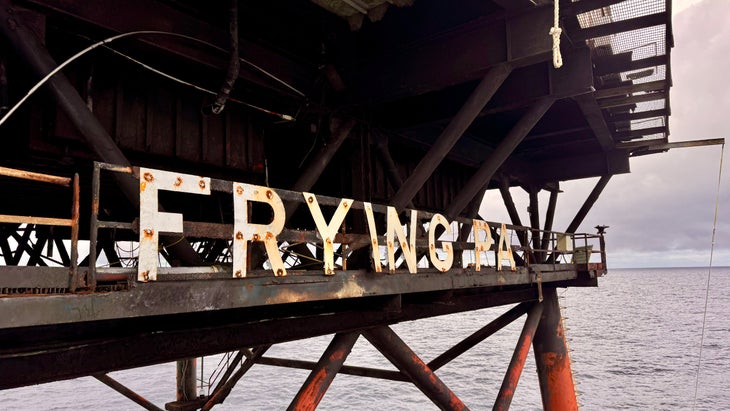

What Is the Frying Pan Tower?

The Frying Pan Tower is a decommissioned Coast Guard light station built on the tip of Frying Pan Shoals, an unusually shallow stretch of water running for 30 miles from the tower west to the Barrier Islands along the coast. Between the 1600s to the mid 1900s, hundreds of ships wrecked on the shoals—known as the Graveyard of the Atlantic—and the lighthouse was built in 1964 by the U.S. government to help keep mariners safe.

The building was decommissioned in the early 1990s when sailors started using GPS to navigate around dangerous obstacles. Frying Pan sat empty until 2010, when Richard Neal, fresh off a corporate job and looking for a project, purchased it in a government auction for $85,000. Since then, Neal has been working tirelessly to restore the structure, passing ownership on to 10 investors and taking over as the caretaker and head of a non-profit, FPTower Inc., tasked with keeping the tower from falling into the ocean.

“Frying Pan can still help keep mariners safe. It’s the only structure out here,” Neal says. Various things can go wrong for ships out at sea, from systems failures to people getting injured. “And it’s a resource for scientific research. We’ve had marine biologists out here, NASA, NOAA, people from MIT. Frying Pan can be a point to collect wave data, hurricane data, shark data…It still has value.”

The ���ϳԹ���s Are Endless at the Frying Pan

It’s also one hell of a basecamp for adventure. Imagine all the benefits of ocean-front property, but put that property in the middle of the sea without any neighbors (or, granted, amenities like grocery stores). Frying Pan sits in only 55 feet of water. On a clear day, you can see the coral on the sandy floor from the catwalk that wraps around the living quarters.

These are ideal conditions for scuba, snorkeling, and free diving. Anglers can drop a line off the edge of the tower and pull up grouper and cobia for dinner. Several times during my two-day visit, I stood mesmerized on the edge of the catwalk watching sharks rise to inspect the bait we cast into the water.

If you get bored with your immediate surroundings, you can explore the Greg Mickey, a fishing vessel about 1,000 yards north that was sunk in 2007 to become an artificial reef in honor of a fallen diver. Or take a 20-minute boat ride to the Gulf Stream for deep-sea fishing for wahoo and tuna.

“I would pass by this tower when I was a kid on small boats, and it was always a comfort to see, because you’re so far away from land,” says Jason Guyot, an owner of Frying Pan who grew up fishing the area with his dad. “It’s nice to know there’s something out here if things go bad.”

And the view? Climb to the very top of the structure, 135 feet above the surface of the water where the actual Coast Guard light stands, and you see ocean. Flat and blue and all around you without a spec of land in sight. As far as vacation real estate goes, it’s one of a kind.

Staying on the Frying Pan

Originally intended to house a crew of 17 Coast Guard personnel, Frying Pan looks like an oil platform. The 5,000-square-foot living space boasts eight bedrooms, a commercial-grade kitchen, two bathrooms, and even an entertainment room with a pool table. A stainless-steel catwalk hangs outside the main floor of the tower, while a helicopter pad occupies the top deck. The actual lighthouse stretches out from that pad, standing 135 feet above the water.

While most lighthouses are located on land, the Coast Guard built seven of these offshore towers, modeled after oil platforms, in the 1960s for added safety. Three of those original towers have been dismantled because of their deteriorating structures; another was destroyed in a storm. The three remaining towers were all scheduled for dismantling until private owners stepped in to purchase them.

According to Neal, Frying Pan is in the best shape of the existing structures, but it still needs constant maintenance. There’s a small movement of private citizens working to preserve lighthouses in this country, and Neal is in the thick of it.

When Neal took over Frying Pan nearly 15 years ago, it had been abandoned for decades. The windows were broken, bullets were embedded in the walls from vandals, it had no power, there were holes in the floors, and rust was eating away at much of the exterior structure.

Restoring the Frying Pan

Neal spends every other week on the tower, working through various projects, while others pop out as often as they can. The renovation project has attracted an interesting mix of investors, all of whom are DIY advocates. They come out together to weld, re-wire, re-build, and generally figure out how to maintain the building. They each bring something different to the situation. One is a helicopter pilot, another a retired contractor. Others are divers and anglers and carpenters, providing fish for the kitchen and practical skills for the restoration.

Technically, Frying Pan is in international waters, so the owners could turn the tower into anything they want–a casino, a bordello, even its own sovereign nation. But they just want to make sure Frying Pan continues to be a resource to the maritime and scientific communities.

The biggest single room is the workshop, loaded with metal cutting-band saws, welding torches, cranes, chains, power cords, two wave runners on racks, massive diesel generators, canisters of oil and soy bean oil. Neal and his cohorts have replaced the windows, installed air conditioning, reconfigured the bedrooms to handle paying guests, and renovated the bathrooms. Neal estimates he’s put $300,000 of his own money into the tower, and it likely needs another $1 to $2 million more to be fully restored.

The largest hurdle in that restoration work is also Frying Pan’s greatest appeal: its location. It’s remote. For my trip, I take a 2.5-hour ride on a 27-foot fishing boat in rough seas and spend the majority of the time trying not to vomit. Supplies need to be either shipped in by boat or flown in by helicopter, neither of which is cheap. This means that Neal and his cohorts end up improvising a lot on site.

“I can’t just run to Home Depot. If I need something, I’m probably going to make it,” Neal says. “If I can’t make it myself, I try to find smart people who can.”

When I reach the tower, Neal and the owners are fabricating braces to hang on the side of the tower to support a row of solar panels, welding together custom-fit stainless-steel tubes. Neal stands on top of a six-foot-tall ladder, set on the edge of the catwalk, roughly 100 feet above the ocean, with a welding torch in his hand to burn a hole into the top of the exterior wall to fit a bracket that will eventually hold the brace for the solar panels.

“I love this stuff,” Neal says, hanging precariously above the ocean with a lit torch in his hand.

While I’m on site, he works from sunup to sundown, tackling one task after another, the half-dozen other owners on the tower at the time working right alongside him. Most of the owners started out as working volunteers, spending a few days on Frying Pan scraping rust or putting down carpet, and fell in love with the property and the challenge of figuring out the solution to the next problem.

Later in the day, Neal and a volunteer will scuba dive below the tower to replace the that stream a live feed of the bottom of the ocean to . After the solar panels are in place, the team will replace some of the exterior doors that are rotting through. Eventually, they’ll have to address some of the structural supports beneath the living quarters that are reaching the end of their shelf life. It all costs money, which is where guests play a part.

How to Visit the Frying Pan

Frying Pan Tower hosts visitors every other week throughout the year, with the proceeds going straight back into restoration. Guests can sign up for a ($900), where they’ll spend most of their time working alongside Neal, welding or cleaning or rewiring. Or they can sign up for an ($1,950) and spend their time diving or fishing or just soaking up the view. When I was there, a volunteer was cooking and the owners brought food, but on most trips you would bring food and cook it yourself.

Most people who find themselves on Frying Pan are infatuated with the open sea. They’re divers and snorkelers, anglers casting off the sides of the tower or taking quick trips to the Gulf Stream. The tower has also seen cliff jumpers and free divers, scientists and Boy Scout troops.

The potential for adventure is only limited by your imagination. Jason Guyot dreams about bringing a kitesurfing rig to the tower and exploring the surrounding seascape. I want to come back with a paddleboard and snorkeling gear. I’d also love to bring my wife and kids; they’d have a blast snorkeling at the base of the tower and watching the sharks from above.

The Stargazing Is Incredible

The night sky is the darkest I’ve ever seen. Not a single light competes for the attention of the stars in any direction on the horizon. Our group of owners and volunteers gravitates to the helicopter pad after the sun sets, and settles in to watch the sky above for shooting stars. The Milky Way is a broad white paint stroke across the darkness.

I don’t go in the water during my brief stay at Frying Pan, but I do help with restorations when I can, hit biodegradable golf balls filled with fish food into the sea below, cast for fish, and generally try to grasp the nuances of life in the middle of the ocean. This is the most isolated I’ve ever been in my entire life. The nearest Starbucks is more than 40 miles due west. If something goes wrong, it would be hours before help arrives.

That sort of isolation makes a lot of people anxious. But for others, it’s relaxing. All of the distractions of life on the mainland are gone. Your priorities shrink. There is only the task at hand, whether it’s fishing or hanging a solar panel, food, and rest.

For dinner, we fire up a grill on the helicopter pad. Jason Guyot, who owns car dealerships and runs a real-estate business on land, is constantly in motion, cooking steaks brought in from a farm in eastern Carolina. He turns the meat slowly, looks around and says, “I wonder what the rest of the world is doing right now?”

Graham Averill is ���ϳԹ��� magazine’s national parks columnist. His time on Frying Pan was brief, but he’ll always remember the brightness of the Milky Way above and the sight of sharks feeding below.

For more by this author, see: