When René Alberto Vera Reyes got on a bus to come to the United States, he was 21 years old. He left the village of Cochrane—in Chilean Patagonia, population 2,000—in April 1999, carrying only a duffel bag that contained two pairs of pants, a pair of riding boots, a couple of shirts, a wool poncho, an awl, and several yards of horsehide pita, thin strips used to weave bridles and bullwhips. To say that René had never traveled would be misleading. He’d roamed all over southern Chile and into Argentina, but he’d done much of that on horseback, in a place where cattle drives still take months at a time. Just to reach Cochrane from the cabin where he was born, René had to ride eight hours.

Nicanor Flores in Idaho

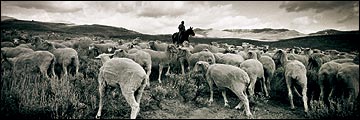

ALONE ON THE RANGE: NICANOR FLORES, HERDING SHEEP NEAR FAIRFIELD, IDAHO

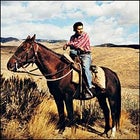

ALONE ON THE RANGE: NICANOR FLORES, HERDING SHEEP NEAR FAIRFIELD, IDAHORene Alberto Vera Reyes in Idaho

GAUCHO: CHILEAN RENE ALBERTO VERA REYES IN IDAHO

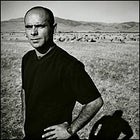

GAUCHO: CHILEAN RENE ALBERTO VERA REYES IN IDAHOHead Rancher John Faulkner in Idaho

BOSS: VETERAN SHEEP RANCHER JOHN FAULKNER

BOSS: VETERAN SHEEP RANCHER JOHN FAULKNERKellye and Rene in Gooding, Idaho

�䰿�ѱʴ�Ñ���鰿�� KELLYE AND RENÉE AT HOME IN GOODING.

�䰿�ѱʴ�Ñ���鰿�� KELLYE AND RENÉE AT HOME IN GOODING.Nicanor at sheep camp

NICANOR AT SHEEP CAMP

NICANOR AT SHEEP CAMPNicanor hearding sheep in Idaho

“THIS IS NOT A LIFE”: NICANOR MOVES THE HERD.

“THIS IS NOT A LIFE”: NICANOR MOVES THE HERD.

What he wanted, though, was to be an American cowboy. He wanted to wear a big belt buckle and Wrangler jeans, and to make enough money to trade his horse for a pickup and to buy land someday back in Chile. To get these things, he’d signed a three-year contract with the Western Range Association, a 200-member Citrus Heights, California–based consortium of sheep ranchers that imports hundreds of South Americans a year to work on ranches all over the West. René had agreed to sign on with a man he’d never met or spoken to—rancher John Faulkner, of Gooding, Idaho—according to terms for which René, it would turn out, was largely unprepared.

As the bus headed north through the Patagonian state of Aisen, a barely populated area the size of Mississippi, there was little to suggest what awaited René in Idaho, aside from the certainty that it would be a different life—a modern cowboy’s life, he hoped—and he imagined walking downtown on a Saturday night and ordering a beer in English. Six hours later, the bus pulled into the Chilean frontier town of Coyhaique. From there, René traveled an hour on another bus to the tiny border village of Balmaceda; an hour and a half on the first plane of his life to Puerto Montt, on the Pacific coast; then another hour’s flight to Santiago, ten more hours to Dallas, and two to Twin Falls, Idaho.

There, one of Faulkner’s ranch hands met René and drove him the 45 minutes to Gooding. After ten days spent helping unload 10,000 or so sheep trucked home after birthing their lambs in the warmer climes of Southern California, René left on his first sheep drive, traveling north from Magic Valley, on the Snake River Plain, across the Camas Prairie and 25 miles into the 2.2-million-acre Sawtooth National Forest.

In all, the trip lasted two weeks and ended more or less right back where it started: in the middle of nowhere.

RENÉ’S YEARS AS GAUCHO—the general name given to cattlemen and sheepherders from Patagonia and beyond, the living embodiment of one of the last great horse cultures on earth—had at least prepared him for the spartan existence he would lead in the mountains. The same can’t be said of Nicanor Flores, the man with whom René would share a camp for the next eight months.

Nicanor had arrived on the Faulkner ranch in December 1998 and gone straight to California with the ewes. He was 27, a city-born Peruvian descended from the country’s native population of Quechua Indians. Nicanor didn’t care about being a cowboy; he only wanted to make enough money to turn around what had been, by any stretch, a difficult life. As a child, he had lost his father and been given to his grandparents to raise. He’d seen them die of cancer; been illegally conscripted into the Peruvian army at age 16, serving two years in the Amazon; wandered around jungle towns living on whatever he could kill with a slingshot; met a woman and had a child; and worked as a ditchdigger and plumber in the Peruvian city of Huancayo. None of this prepared him for the difficulty of trying to get a job in the U.S.

Having first secured a recommendation from his girlfriend’s father—a man who’d worked five contracts with Western Range—Nicanor made the six-hour bus trip from Huancayo to Lima to register with the company’s Peruvian office, where he was told there were no openings; he’d have to call back later. He had no phone, so for the next month and a half, back in Huancayo, he sneaked into his boss’s office at the plumbing shop to call Lima whenever he could. And for a month and a half, the Western Range secretary said she hadn’t heard anything. Then one day in December she announced, “The plane leaves in 48 hours.” He would fly out of Lima—bound for Gooding, Idaho.

Preparing for a three-year trip in one day is not easy, though Nicanor put the best possible spin on it, which was that it didn’t allow for sad goodbyes or being frightened by the long list of things—a country, a job, and a language among them—that he knew absolutely nothing about.

After three days of traveling, he reached Twin Falls. It was dark, and freezing cold. Nicanor had understood that he’d be working in a desert, so he hadn’t packed winter clothes. He had never seen snow in his life. For that matter, he had never even sat on a horse.

I FIRST MET RENÉ AND NICANOR in September 1999, at their tent camp in Idaho’s Skeleton Creek drainage. For the next five years, I followed their lives—partly because I grew to care about them and partly because I was captivated by the story of two men who’d left everything behind to find a new start thousands of miles from anything they’d ever known.

Americans think of the frontier as being long closed, but for people like René and Nicanor—and for millions of others who dream of a richer existence in the U.S.—it remains wide-open. Over time, watching the divergent paths they followed left me amazed by the longing that drives such adventures, and by what they entail. There’s opportunity, to be sure, but also terrible hardship. And despite my own once-soaring images of life on the open range, there’s little in the way of romance.

I arrived at Skeleton Creek with a Basque immigrant named Julian Larriebia—John Faulkner’s majordomo, or ranch foreman, for the past 46 years—as he delivered biweekly supplies to René and Nicanor and the dozen or so other herders working in the national forest. From Gooding we drove to Fairfield, a small town 30 miles north, and followed a dirt road a half-hour through chaparral-veined foothills before entering the mountains on the first of several Forest Service logging roads. The ruts got deeper and the going slower, until Julian’s old Ford pickup was moving more up and down on its shocks than forward on its wheels.

Forest Service Road 014 came to an end at a meadow filled out in Indian paintbrush and fringed by yellow-leafed aspens and shady firs. Along the edge of the forest, still far away and tiny, René’s and Nicanor’s horses, a black gelding and a dappled gray mare, picked their way downslope, followed by a string of mules. René wore a miner’s beard, a greasy baseball cap, jeans, and a T-shirt with the sleeves cut off. Across the pommel of his saddle he carried a Chinese-made semi-automatic rifle that he used to kill black bears and mountain lions that threatened the 1,300-animal herd. Nicanor, whose skin was a deep cocoa-brown, rode the gelding with no saddle, just a blanket; he was shirtless, and his shoeless, callused feet were caked with dust.

“Están atrasados!” Julian called out in his lisping Continental Spanish—”You’re late”—a joke he liked to make about the hit-or-miss nature of supplying people who steer themselves in the wilderness with nothing but pencil-sketched routes on old Forest Service maps. As the riders dismounted, Julian finished stacking the few crates of supplies—eggs, garlic, mayonnaise, oil, and salt, along with cigarettes René had bought. It didn’t take long to load the provisions into pack bags carried by the three mules. Then, just as quickly as it began, René and Nicanor’s brief contact with the outside world was over, and the three of us—with me sharing Nicanor’s horse—were riding back up the trail through the trees.

Above us that day was a bald ridgeline, and as we came down the other side we could see for 70 or 80 miles, through the foothills and across the Camas Prairie to where the Snake River Plain abutted the Idaho Batholith in the hazy, unsure distance. It was dry, austere terrain that was a world away from anything René or Nicanor had ever seen, and they were not immune to its loneliness. With his tongue, René drew a corner of his long mustache into his mouth and chewed it as the mules began to bray.

“I don’t know,” he quietly said to Nicanor in Spanish, “if I can stand this isolation much longer.”

THAT A GAUCHO WOULD TRAVEL all the way to Idaho in pursuit of the cowboy myth is ironic, given that the number of people we think of as real cowboys in the U.S.—people who spend long periods on horseback working with herds—has dwindled to almost nothing, thanks to the brutal economics of ranching and what can only be described as loss of habitat: the fencing of the range.

On many ranches, trucks have replaced cattle drives, roads have replaced trails, and four-wheelers have replaced horses. While there’s still a need to break horses and drive cattle across the West’s biggest ranches, there’s really only one job that requires spending months at a time following stock on horseback: sheepherding on millions of acres of leased federal land.

The fact that South Americans now do the work is part of a larger phenomenon, the Latinization of the American West. In towns like Gooding, Idaho, and Ely, Nevada, Latinos—predominantly Mexicans, here both legally and illegally—have taken low-paying jobs in construction, road building, restaurants, and ski resorts. Those hidden deepest from view are people like René and Nicanor, the gaucho and the city kid, riding the range like Americans did a hundred years ago. Or like Latinos did 250 years ago: The word cowboy, after all, is a translation of vaquero; the western saddle is actually a Mexican saddle; and much of the West once belonged to Mexico. Five hundred years after the conquistadores, history has come full circle. The last cowboys speak Spanish.

The U.S. Department of Labor describes the situation less mythically. In its lexicon, René and Nicanor are not horsemen at all; they are “nonimmigrant guest workers,” as designated by a portion of the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act known as H-2A. Under H-2A, American farmers and ranchers offer contracts every year to some 45,000 workers, mostly Mexicans, the bulk of whom pick produce from California to Florida. Around 1,200 of them, however, come to herd sheep in 13 western states, from Oregon to South Dakota. Almost all are from Peru, Chile, and Mexico—though in Gooding, I met one Mongolian H-2A herder.

Since 1955, the H-2A program has given two companies—Western Range and the Mountain Plains Agricultural Service, an outfit based in Casper, Wyoming—wide leeway to act as middlemen between ranchers and the Department of Labor. And since it imports the vast majority of herders, Western Range has been the target of criticism from labor advocates who find the entire arrangement abusive and unfair.

“H-2A is the last American frontier of exploitation,” says Bruce Goldstein, co–executive director of the Farmworker Justice Fund, a nonprofit advocacy group in Washington, D.C. There is, he alleges, essentially no public control over this system: The companies, not the government, administer the workforce. This dearth of oversight, activists argue, has led to several well-documented cases of abuse. One family outfit near Craig, Colorado—John Peroulis & Sons Sheep Inc.—was investigated by the Department of Labor six times between 1993 and 2000. The most recent investigation involved the beating of a Peruvian herder named Remigio Damián, who was hospitalized after wandering for four days with head and neck injuries. Eight Peroulis employees deposed in U.S. District Court in Denver recounted a slew of alleged abuses. Although the Peroulis family has paid fines and back pay in the past, and in 2001 agreed to a civil settlement of the Damián case with the Department of Labor, they have repeatedly denied mistreating foreign workers.

Sheepherders are basically powerless in such situations—if they quit, they can be deported—and the pay’s not much, either. In 1999, René was making $700 a month, the equivalent, based on a 40-hour week, of $4.37 an hour for a job defined by the government as “being on call to protect flocks from predators 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.” Considering that he was on duty around the clock, René’s hourly wage was more like $1.50.

With the harsh conditions and pay scale, it’s not surprising that, every year, 5 to 10 percent of H-2A contractees “irse mojado“—”go wet.” René realized almost imme- diately after arriving in Idaho that he could make money faster as a dishwasher or a carpenter, even if it put him outside the law. He also learned that there’s one legal way to void a contract without the Immigration and Naturalization Service looking for you: marrying a U.S. citizen.

RENÉ AND NICANOR’S camp sat beneath pine trees alongside a creek, an hour’s ride from the logging road where Julian had dropped their supplies. Their dirt-floor, canvas tent was held up by Douglas fir saplings. Inside were two fold-up cots, each with a sleeping bag and a rolled jacket for a pillow; a wood-burning stove; a frying pan; two aluminum mixing bowls; a bag of dog food for the Australian shepherds that guarded the sheep; and two buckets of grain for the horses. A side of ewe hung off one of the fir poles, leathery and dry. A piece of fat the size of a baseball mitt was nailed below, which René and Nicanor used to season the pan. Some men, if you added up all the eight- and nine-month stints they’d done on multiple Western Range contracts, had spent a solid decade, or even two, living like this.

On the surface, two less compatible tentmates could hardly exist. Peruvians and Chileans still remember that in 1882, Chile invaded Peru and seized hundreds of square miles of nitrate-rich desert whose mineral extraction has since helped drive Chile’s economy. Add to this the fact that many Chileans look down on the indigenous Peruvians as “docile” (to use René’s word), not to mention tight with money when sober and cheats when drunk, too sympathetic toward animals, and overly fond of chicken instead of mutton, which gauchos eat three times a day.

Even so, the two men got along well here in the mountains, where the politics of survival superseded those of culture and history, and where René, with his experience, was clearly the boss. In the mornings and evenings, René rode out to count and check the sheep; every three to five days, depending on how quickly the animals grazed an area, René decided to move them. Nicanor cooked the meals, which he had waiting each morning and night.

The afternoon we left Julian, René and Nicanor had moved the herd roughly a mile, though Nicanor was unsure if they’d ended up in the right place—a constant source of tension, given that, if they veered off course, they would miss Julian and his supplies in another ten days. Nicanor kept looking suspiciously in the direction of the bubbling creek, as though it were whispering lies.

“I told you, ����ܱ�ñ��,” said René, “we’re at the right creek.” He pointed to the soft flesh of the aspens all around, where men had cut their initials and nationalities like prisoners marking the passage of time—a sign that the site was often used by herders.

“Then why is that creek so low, ����ñ�����?” said Nicanor. He was worried that there wouldn’t be enough water for the sheep.

“Just trust me,” said René.

Nowhere were the complexities of René and Nicanor’s relationship more evident than in the way they spoke, a mixture of two of the most distinctive Spanish dialects in Latin America, cut occasionally with Mexican-influenced Spanglish. René, though he was shorter and younger than Nicanor, called his companion ����ܱ�ñ��, “little one.” Nicanor called René ����ñ�����, “brother-in-law.” Together they referred to themselves as compañeros de tenta, “tent partners.” And in a biting allusion to the fact that two young men would be stuck together so long without hope of even seeing a woman, they changed this occasionally to compañeros de tentación, “partners in temptation.”

René talked incessantly about what he’d left behind, filling in Idaho’s alien space with a familiar Chilean landscape. As we talked that first night, sitting beside the fire, he began telling the tale of how his grandfather, a carpenter, came to Patagonia in the 1930s from northern Chile and became a gaucho. As he told the story, he whittled a stick with a knife his grandfather had given him: a long, slender blade whose black handle was fashioned from the enormous middle toe of an ostrich. Nicanor watched René stop to drink from a jug of Carlo Rossi white Grenache, his reward from the ranch for killing a black bear the week before.

Racism was a favorite topic of René’s, and he ended by saying, “In Chile, my grandfather could become a gaucho; he could become anything. It’s not like here, che, with all the discrimination.” “Really?” asked Nicanor. As a Peruvian of indigenous descent, he’d seen his share of bigotry.

“Yes. Really.”

“���ñ�����,” said Nicanor, “what do you know about Chile?” When René looked at him, Nicanor quietly returned his stare.

“The reason you think there’s no racism in your country,” Nicanor continued, “is because you’ve never seen your country. It sounds like there’s no one in the part of Chile you come from.”

He was right: Less than 2 percent of Chile’s population lives in Patagonia. “If there’s no one to hate,” Nicanor concluded, “no one will hate them.”

For a while, René was quiet. “Esta no es vida,” he said finally, looking at the shadows of the campfire’s flames moving against the tent and, above that, the millions of stars in the sky.

“Yes,” Nicanor countered, “this is a life.” When René looked at him, angry about having been challenged again, Nicanor smiled brightly in the firelight. “It’s just a shitty one,” he said.

FAULKNER LAND AND LIVESTOCK runs 50 miles west and 80 miles east out of Gooding—as far as you can see. Early one morning in September 1999, just before I headed out to camp with René and Nicanor, I sat with John Faulkner in his office. By all accounts, he was a decent boss. The Patrón—or the Lieutenant, as his men sometimes call him, as much for his quiet, disciplined manner as for his Army service—was always described as fair.

Faulkner wore jeans faded at the knees, a broad hat, and photochromic sunglasses. He had small, dark-blue eyes, a white beard, and the carriage of a man who’d worked livestock for all of his 67 years: strong shoulders, a widening belly, and a stubborn walk that didn’t hide a ginger back. His desk was covered with bills and affidavits and newsletters explaining updates in environmental and immigration laws—the vast paperwork of an operation subject to regulation by 24 government agencies.

To Faulkner, South Americans are essential, because locals won’t work range jobs. “Americans want a shower,” he said. “They want a warm bed; and insofar as there are herding jobs anymore, nobody wants them, because it means you can’t come in to the bar on Friday night. It’s progress.”

H-2A, he said, was keeping him in business. (Since then, wool prices have quadrupled, rising from 23 cents a pound in 1999 to $1.06 today. But the reality is that this spike has come at the tail end of two decades of crippling competition from Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and Argentina.) “In the past 20 years,” Faulkner said, “the number of range operations in Idaho—ranchers with more than 1,000 head of sheep—has gone from 60 to 30.” He took off his hat and glasses and rubbed his face, cutting right to the point. “René and Nicanor live in pretty primitive conditions. But that’s the way it’s always been with this business, ever since my father was a boy living in the same mountains. If they don’t want to work, fine. A lot of other men do.”

���ϳԹ���, six men in dirty coveralls and cowboy boots worked under the brilliant sun, repairing machinery in front of the equipment shed, their singsong Spanish audible in the background.

Later that night these same men would sit around Faulkner’s 20-man bunkhouse, as they did most weekend nights, and drink beer before going to town. It was a ritual that those out on the range, like René and Nicanor, could rarely share. Wearing boots and jeans and snap-front shirts, the hands would set out en masse, as a protective measure. This was for two reasons: Many locals resent the herders—as one Anglo put it to me, “A white man can hardly get a job anymore”—and Gooding, like many western towns with broken economies, has become a much more dangerous place as the methamphetamine trade has moved up the Rockies from Mexico.

Around 9 p.m., a brand-new Ford F-350 pulled up to the bunkhouse. In the cab were three Mexican kids and a skinny Anglo from town wearing ruined Lee jeans, a dust-covered denim shirt, and a humongous cowboy hat. Holding a Tequiza among the brown-skinned Mexicans, in their Tommy Hilfiger golf shirts and baggy jeans, the American could not have looked more out of place. In Gooding, the Mexican meth dealer cruised in the F-350, and the drugstore cowboy rode shotgun.

Inside the bunkhouse, it smelled like mildew and backed-up toilets and cologne. The three Mexicans yelled hola to the men who peeked out the doors lining the dark hallways and sang along with the new Carlos Vives song that played on the truck radio and from stereos in every room. One of the truck passengers, a 19-year-old kid I’ll call Angel, slouched in the doorway of a room, inside of which a tall Chilean gaucho in his forties, Jorge Silva, was using a homemade knife to cut lonjas, tenth-of-an-inch-wide strings of hide, for a bridle.

Angel told me that he was here to “make some sales,” and when I asked what kinds of things might be for sale around Gooding, he mentioned not just meth but cocaine and painkillers. Chances he’d make any deals in the bunkhouse were slim, however, given what his potential clients earned a month, and given that the gauchos tend to disdain Mexicans and stay away from anything stronger than alcohol and tobacco. Still, Silva and the others gave him a friendly greeting, joking about Angel’s last illegal run into the U.S. across the Mexican border. In the end, what mattered was that the gauchos and the meth dealers were part of the same picture. Like the wool from Australia, they had been imported into a part of the U.S. that had, as a result, been changed forever.

ONE NIGHT DURING THE TIME I spent with René and Nicanor, René made bistec a la pobre, “poor man’s steak,” a delicacy among gauchos. First, he cut slices off the ewe hanging from the tent pole. Then he seasoned a corner of the stovetop with a piece of fat and laid down a few slices. When they were nearly done, he seasoned a new spot and fried eggs there, then put the eggs on the meat.

When he’d finished eating, René looked off toward the black body of the mountains, rimmed by the palest moonlight against the sky. In the middle of the blackness, there was a tiny pinpoint of light.

“Oye?” he said: “Hey?”

Nicanor looked, too—the light was getting closer.

In Patagonia, more gauchos believe in witches, ghosts, and the devil than believe in God, and they often debate the different ways that spirits show themselves to people. Witches and ghosts appear as wavering points of light, they’ll tell you, while the devil travels alone at night, a gaucho wearing all black and riding a black stallion. Where his face should be, there is only polished black rock. If you dare to look, you will see only your reflection.

Suddenly there was the sound of hooves on the rocks. René rose and picked up the rifle, checking the breech in the firelight to make sure it was loaded.

A minute later, a man and woman came into view, each leading a horse. The man had on a big, white cowboy hat, white chaps, and a shiny white shirt with leather cufflets—a clown to the gaucho devil. The woman was dressed in a riding skirt, ornate blue-and-white boots, and a suede vest. The man held a small flashlight; aside from that modern touch, they looked as if they’d ust escaped from Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show.

“Ask them if they’re lost,” René said to me in Spanish, relaxing to let the rifle lean against his shoulder. I did.

“Obviously,” called the man. But he didn’t stop walking, and he didn’t say anything else. He and the woman were miles from the nearest road. We watched them for a long time, until the flashlight beam no longer showed on the trail.

“First people we’ve seen in two weeks,” said Nicanor.

“Cowboys,” said René, mesmerized. “But at first I’d have sworn they were ghosts.”

A FEW MONTHS LATER, RENÉ and Nicanor came down out of the Sawtooths, crossed the prairie, and landed back at Faulkner’s place. They spent Christmas 1999 and New Year’s in the California alfalfa fields for the ewes’ birthing season. By Easter they were back in the mountains, this time working alone in separate camps. But not before René met Kellye Whiteman.

“I was the first gringa he saw,” Kellye told me, laughing as she recalled the day they met in Gooding’s farm co-op, where Kellye was picking up a cup of coffee on her way to work at the Diamond M Ranch, where she branded cows. “Even with that beard, he looked like a scared little boy.” The attraction was immediate, however, and a week later, when they met again at the Lincoln Inn, a steak house and bar where Kellye used to sing karaoke, they spent the night in her trailer on Nebraska Street.

Kellye was 38 at the time—René was 22—with blue eyes and bright blond hair. She was tall, five foot nine to René’s five-six, and her pale skin was interrupted from right knee to hip by tattooed tiger stripes. Originally from Granseville, Idaho, Kellye had moved to Gooding in 1993 after stints in Oregon and Alaska, so that her daughter, Kelsey, could attend the Idaho School for the Deaf and Blind. (Kelsey was 13 and in the second grade; she was born with cerebral palsy and, as an infant, had suffered seizures that left her deaf and mute.) Kellye’s son, Bryce, was 17; she’d taken him out of high school the previous year to homeschool him after catching him smoking pot. Kellye had called the police, and Bryce had been busted for possession of marijuana paraphernalia with the intent to use, an offense for which he was on probation for nine months.

To put Kellye and René’s age difference in perspective, consider that René’s mother is only 19 months older than Kellye, a fact that didn’t bother René during a sporadic, intense courtship that lasted the entire nine months he spent back in the Sawtooths. Whenever it looked like his herding route would take him close to a logging road, Kellye and Kelsey would drive out, and the three of them would ride René’s horses and hike to gather the rams. Kelsey taught René some sign language, and Kellye taught him some English. Both Kellye and René describe those months as some of the best of their lives.

For René, there was something else: One day, Kellye gave him an engraved silver pocket watch. It was the first thing anyone had ever given him. Whenever René thought about Kellye’s kindness, it made him cry. He took it as a sign that the world he’d been so unprepared for had suddenly given him a larger gift: a woman he loved, an answer to the crushing loneliness, and (just maybe) a way out of his contract. In July 2001, 15 months after they met, René voided his deal with Western Range and married Kellye, an occasion she commemorated with a tattoo above her heart of a chile in a sombrero and sunglasses. The newlyweds set up house in her trailer. René, it seemed, had finally made it to America.

NICANOR, MEANWHILE, had gone home and come back again. After his first three-year contract with Western Range expired in the fall of 2001, he’d returned to Huancayo, bought a van, and started ferrying tourists around the city. But by March 2002 his business had failed, and he was back working for Faulkner. I visited him that September. He was camped in a patch of alfalfa near Fairfield, with 1,500 sheep and a new compañero de tentación: a window installer from Lima named Gabriel.

It was hot when I reached their camp, and Nicanor and Gabriel were sitting in the dusty shade of a carrocampo—a sort of horse-drawn covered wagon. Nicanor wore a multicolored striped oxford shirt with the tails tied at his waist. He’d gotten a new gold cap on one of his incisors, a decorative touch that flashed when he smiled.

Nicanor was now the camp boss, and with the new responsibility there was a boldness about him—even a hardness: When I asked about a mule deer skin stashed in a corner of the carrocampo, intact save for a large bullet hole where the ribs would have been, he simply said that he and Gabriel had gotten sick of mutton.

“I’ll never kill another bear, though,” he said. “The last one—I cut off his paw as a keepsake, and it really upset me.” I asked him why. “It looked like a human hand,” he told me, “with long fingers and wrinkly palms. I wish I’d never killed one.”

Gabriel was a slight young man of 21 who looked even younger. He had wide, wet, black eyes and wore the practiced look of someone trying to appear more stern than he was. Then he’d say something funny—quickly, with a nodded affirmation to himself—and break into a broad and easy smile.

Watching Gabriel next to Nicanor, I thought of something Faulkner had told me about the herders. “They’re their own worst enemies,” he’d declared. “One or two will do the same thing every spring: run off and start working construction in some town somewhere. Winter comes and they’re starving to death, so they come back here. Happens all the time.”

What Faulkner wasn’t saying was that someone like René or Nicanor takes a huge gamble in order to have a better life. They lose touch with everything they’ve ever known. And when it becomes clear that all of their suffering has ended in disappointment, there are only two options: Go home or keep gambling. René, for one, had come too far to go home.

DURING THAT SAME VISIT, René and I met on a Sunday afternoon at the Lincoln Inn. He was 25 now. Eighteen months after quitting his ranch job and marrying Kellye, he was clean-shaven and wore his receding black hair clipped nearly to the scalp. He looked much older, but also more handsome. He wore Wranglers, a denim shirt, good boots, and a belt with a buckle you could have fried eggs on.

René, in the modern American way, had become a cowboy. He lived in a small town with his wife and worked construction. He listened to country music and, on weekends, put on his good boots and walked down Main Street. But the dream, such as it was, had failed him. More than ever, he longed to go home to Patagonia. “Sometimes,” he said, “I wish I’d never left in the first place.”

At the moment, René and Bryce were working construction, building a big house on a quaint road up in Ketchum, 70 miles north of Gooding. For René, it was the best way to make ends meet—he could legally work now that he was married—and for Bryce it was a kind of drying-out period after the pot bust. He and René would leave Gooding at five o’clock on Monday mornings, drive to Ketchum, and put in 10- to 12-hour days. They spent Monday and Tuesday nights in the sheep camp of a Chilean and Peruvian with whom René felt more at ease than anyone else. On Wednesdays, they’d drive back to Gooding, then spend Thursday nights back at the sheep camp. Bryce, though he had no experience, started out making two dollars an hour more than René.

Bryce was tall and thin, with soft eyes and freckled skin. He was smart and bluntly articulate; he explained his complete lack of ambition by saying, simply, “Ranching families are the only someones in Gooding. Everyone else is fucked.” Of his new stepfather, Bryce said, “I don’t get him. It’s just a totally different culture.”

René’s marriage was itself a case study in culture shock. “This was a big step up for René,” Kellye had told me, “having indoor plumbing and electric lights for the first time. I mean, he’s from nothing—nada. It took him a week to figure out what a coffee machine did.”

Unfortunately, the differences that had seemed exotic were now driving the marriage south. Kellye said she thought René was a machista, and that he thought she was loose. “He doesn’t understand,” Kellye said, “that if you think you can go out and party alone and leave your wife at home … that this is America, not Chile. Your wife is going out to dance on the tables, too.”

That afternoon at the Lincoln Inn, René looked at a bumper sticker behind the bar that read WANNA GET LAID? CRAWL UP A CHICKEN’S ASS AND WAIT and told me he and Kellye fought almost constantly. The most divisive issue was that René still sent most of the money he earned home to Chile, where his father was using it to buy cattle for him. Someday, René said, he’d start sending money to buy land to run them on. Kellye resented this deeply.

What René wanted had not changed much since he’d first come to Idaho. What had changed was what he was willing to do to get it, and once again he was thinking hard about running away, this time from Kellye. He was thinking, he said, of going wet.

René ordered another Budweiser and, as he always did, pushed his index finger into the neck of the bottle, where it was briefly stuck before coming out with a pop.

“I think sometimes about going back to Chile with Kellye,” he said in his thick gaucho Spanish. “But then I think about the three of us, Kellye and Kelsey and me, che, all alone with the cattle.” He made a face like he was smelling feces.

“That dog,” he said, “would shit on his leash.”

THE LAST TIME I TALKED with René was on the telephone in May. He was in the process of divorcing Kellye, he said, and was mulling his options: Once the divorce was finalized, in July, he figured he would probably return to Patagonia and start tending the cattle his father had bought for him. I asked about Nicanor.

“Run off,” said René. I could almost see him smiling into the receiver.

“Where did he go?”

“Who knows?” René said. “It’s a big country.”

The moment was a strange echo of the last time I’d seen both men together, back in 2002. I’d gone with René and Kellye to visit Nicanor, who was still camped in the alfalfa field with Gabriel. It was the first time in more than a year that René and Nicanor had seen each other, and they stood outside the carrocampo in the sun and talked, slipping quickly back into the amalgamated slang they had developed in Skeleton Creek. Kellye, who speaks no Spanish, kept putting her hand in René’s back pocket and, at the same time, leaning away from him. Next to her, René looked small as he told Nicanor in Spanish how deeply unhappy he was.

“Then what’s next, ����ñ�����?” asked Nicanor.

“There’s a cheap room for rent in Shoshone, ����ܱ�ñ��,” said René. Shoshone is a quiet town of a couple thousand people, 20 miles north of Gooding.

“If you’re going to run,” said Nicanor, his gold tooth catching the sun as he grinned, “then you’d better go farther than that.”