DAWN WAS BUT A RUMOR on the eastern horizon when our climbing team set off from base camp, heading north toward a mountain so elusive it wasn’t even named until 1998. By 11:30 a.m., after a morning of steady advancement, our party of seven had gained the summit ridge. No one was showing signs of edema; we pushed for the top…

Hike the Heartland: Mountains of Kansas and Iowa

Hike the Heartland: Mountains of Kansas and Iowa

Hike the Heartland: Mountains of Kansas and Iowa

Suddenly, a large creature stormed our right flank. Crowned by a woolly gray mane, it walked erect and emitted humanoid noises. “Egad!” I exclaimed, flinching. Was this the fabled yeti, terrorizing another doomed high-altitude expedition?

No. It was retired farmwife Donna Sterler, who emerged from her white clapboard house with a hearty midwestern hello.

“Welcome to our home,” she chirped. “And the highest point in Iowa!” She passed out plastic key chains that read HAWKEYE POINT, ELEV. 1,670 FT., and then pointed toward some farm buildings and a million ears of corn. “The summit is over there,” she said. “To the right of the cattle trough.”

We climbed six, maybe eight feet and conquered the first of the Seven Summits.

Big-time climbers will object, saying the Seven Summits consist of the highest mountain on each continent, and Hawkeye Point definitely isn’t one of them. But that’s a modern alpinist for you: an unthinking yes-man, toeing the company line. Do these so-called mountaineers even bother to explore anymore? It seems to me they just mindlessly follow lemming tracks up places like Rainier and Everest, blathering about European knots and turnaround times, rarely attempting anything new.

What would George Mallory think? Would he feel kinship with monkeys who climb “because it’s been doneÔÇöoften”? Hardly. I think he’d be more impressed with seven slow-footed high school buddies who decided, for no good reason, to stage a reunion in which they claimed truly unknown peaks far off the beaten path. Namely, the roofs of Iowa, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas.

It was all my twin brother’s idea, actually. A California-based documentary filmmaker who helmed the riveting A&E special on the history of cleavage (called, helpfully, Cleavage), Dave figured he could squeeze a film out of our still-close gangÔÇötwo decades after graduationÔÇöas we schlepped around in a van, notching heartland “peaks.” Though we wouldn’t be the first to take on seven relatively lame summitsÔÇöway back in 1987, a group of Kansans blitzed through Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, and OklahomaÔÇöwe liked to think we would do it with a style and lack of grace all our own.

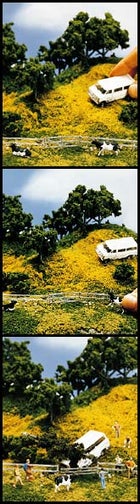

So it was that, at the start of a long holiday weekend, Dave convinced six of usÔÇöCasper, Drew, Spade, Dorrell, Steve, and meÔÇöto assemble with him at base camp (that is, our parents’ homes in the suburbs of Kansas City, Kansas, where we’d grown up). There, we loaded sleeping bags, mats, climbing gear (sport sandals and Hawaiian shirts), and an ammo box stuffed with 98 Nicaraguan cigars into a rented 15-passenger Ford Econoline Club Wagon. At exactly 5:17 a.m. on a Friday, we set off for peaks that Reinhold Messner has never mustered the courage to challenge, on a journey that would demand more than 3,100 miles of motoringÔÇöand fully 17.8 miles of strolling …er, I mean hiking and climbing.

And now, just six hours and one greasy breakfast later, we’d bagged our first peak and were ready to aim the Econoline northwest, toward the Dakotas. Triumphantly, we descended the summit ridge.

Or, as Donna Sterler called it, “the driveway.”

“TRAVELING TO STATE HIGHPOINTS involves healthy outdoor recreation with concomitant learning of state and regional geography and history….It can expand the senses and bring joy to the heart.” This according to a 1997 journal article called “Highpointing”ÔÇöSummiting United States Highpoints for Fun, Fitness, Friends, Focus, and Folly, written by Thomas P. Martin, a health professor at Wittenberg University, in Springfield, Ohio.

Martin rated America’s 50 state highpoints using a ten-point scale of difficulty, with Florida’s 345-foot Britton Hill earning a mere 1 and Alaska’s Mount McKinley, at 20,320 feet the tallest of them all, getting a 10. In between are drive-ups like Rhode Island’s 812-foot Jerimoth Hill and airy scrambles like Idaho’s 12,662-foot . He informs us that highpointing was first mentioned in a 1909 edition of National Geographic and that a 1986 ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° item about the pastime spurred the establishment, in Mountain Home, Arkansas, of a national Highpointers Club, some of whose 2,700 members amuse themselves by seeking the second-highest point in each state. One of the leading guidebooks, Highpoint ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°s, published in 2002 by Colorado highpointers Charlie and Diane Winger, points out that more than 800 people have successfully climbed Mount Everest but only 100 or so have claimed all 50 U.S. highpoints.

Interesting. But we felt disconnected from Thomas P. Martin’s world of wonder even before Iowa’s flapping cornfields gave way to the arid vastness of the Great Plains. See, traditional highpointers are like birdwatchers: They have time on their hands, and they’re willing to spend decades adding to their life lists. We had just one long weekend to get the job done, and as the Econoline chugged westward, our task seemed as immense as the sky.

The basic plan was to bag peak two in North Dakota, then work our way in a southerly and easterly meander through South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas before zipping back north to Kansas City to catch our flights. Friday night found us at the Butte View Campground, in southwestern North Dakota, sleeping under stars that never have beenÔÇöand probably never will beÔÇösullied by urban light pollution. Butte View also boasted excellent bathrooms, and the next morning its showers wooed six of us. Only CasperÔÇöwho insisted we were moving too slow, since by this time we’d climbed only one peak in 26 hours of travelÔÇöbegged off. Little did we realize that his refusal to groom when he had the chance would later imperil our entire quest.

We packed up and drove roughly 25 miles to White Butte, at 3,506 feet the highest point in NoDak. Like Hawkeye Point, White Butte towers above private property. Unlike Hawkeye Point, its owners don’t give anything away. We had to pay a woman $20 to climb itÔÇöand she didn’t even hand out key chains! Fortunately, the cost was offset by the stark beauty of the sandstone formation, which gave off fine white dust that coated everything. Even the bugs, which were big and plentiful. As a note on the summit register put it, “the crickets scared the crap out of me!”

We ate breakfast in Bowman, North Dakota, at a place called the Gateway Cafe, a fine establishment that furnished sticky buns and a local newspaper, The Dickinson Press. Its lead story: A 70-year-old woman touring nearby Theodore Roosevelt National Park had been seriously injured after getting gored by a bison, thrown 20 feet into the air, and impaled on a tree.

This troubling news gave us much-needed perspective. Though a three-hour drive and our highest summitÔÇöSouth Dakota’s 7,242-foot Harney PeakÔÇöawaited, we were ready, willing, and punctured by neither horn nor branch: the Chosen Ones of the Great Plains!

I DON’T KNOW OF MANY high school posses that have stayed as close as ours. This happened, in part, because my buddies and I liked high school so much that we’ve mythologized it. (Hey, it happens. Call it the Diner syndrome.) Steve served as student-council president; Dave was veep. Dorrell edited the yearbook. I worked for the student newspaper and was lineman of the year on the football team. Spade was a star golfer. Casper was the class clown. Drew, who gets along with everybody he meets, was one of the most popular guys in school. Our friendships have never faded; we would march to the grave for one another. And though we’d all made it to our 20th high school reunion the summer before, we relished a chance to meet up again.

Which is how we found ourselves roaring past Mount Rushmore with barely a glanceÔÇöwho needs it?!ÔÇöheading merrily toward South Dakota’s apex. On the Martin difficulty scale, Harney Peak is a 4, thanks to its height, its 1,500 feet of vert from trailhead to tippy-top, and its round-trip hike of 5.8 miles. A sign on the summit reminds visitors, incorrectly, that Harney is the highest point between the Rockies and the towering Pyrenees of Spain and France. It’s capped with an elegant stone lookout built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in 1939.

Of course, there’s a built-in problem with a soaring, 7,000-plus peak: It’s a real mountain, so it attracts real mountaineers. At the summit, while taking celebratory sips of whiskey from my Kansas City Chiefs flask, we were approached by an athletic couple from Colorado. Mistaking us for like-minded “serious” climbers, they gushed, “You gotta go sit in the Chair!”

The what?

“An armchair-size divot in the cliff just downhill from here,” one of them explained. “You can sit in it and dangle your legs over 300 feet of nothingness.”

This intrigued Steve, who just can’t resist a challengeÔÇödespite his utter lack of coordination and kinetic awareness. One time in high school, Steve tried to hurl a pack of lit firecrackers out a half-open car window and hit the glass instead. The fizzing explosives tumbled to the floor of Drew’s mom’s Thunderbird, blowing a hole in the carpet.

While Steve managed to sit in the Chair without tragedy, the sight of him wiggling on the precipice made the rest of us hit the flask repeatedly. We drank more that night at dinner, which meant the only sober driver available was . . . Steve. He gave up drinking a while ago, but he remains, quite simply and without peer, the worst driver of all time, constantly alternating between sudden acceleration and braking. His hands shake constantly; throw in his current addictions to coffee and cigars and you get transport that is, at best, fumbling and herky-jerky, at worst, upside down in a ditch, surrounded by flashing lights.

As Steve pointed us toward Nebraska, Spade, Dorrell, Dave, and I nodded off. Drew and Casper claimed they “couldn’t sleep in cars” and watched Steve driveÔÇöwith the color drained from their faces and their fingernails dug deep into Econoline vinyl. Whatever they did as backseat drivers must have worked, because Steve successfully, if shakily, kept us on the road.

IT WAS 2 A.M. ON SUNDAY by the time we reached the highest spot in Nebraska: Panorama Point, a 5,424-foot bulge in the extreme western part of the state, near the forlorn three-way junction with Wyoming and Colorado. Though Panorama is more than a mile high, you can’t exactly rappel off it. It’s a big mound with a crude metal-and-stone marker on top, put there to remind you that it’s something special. We pulled the Econoline within six feet of the marker, unfurled our bags, and slept on the summit itself.

We woke shortly after dawn to the lowing of bison from a ranch located half a mile south, in Colorado. Dave got on top of the Econoline to get a bird’s-eye digicam view of the utterly horizontal summit, and then we were off. Thirsting for a strong cup of joe, we kept our sand-encrusted eyes peeled for any sign of gourmet coffee. But the Great Plains is the only region in the lower 48 where you can drive for four days and never see a Starbucks. We settled on a venerable diner, the Longhorn Cafe, in Kimball, Nebraska, and sat among ranchers sporting their Sunday-best Stetsons. Near a pot of bitter brown water masquerading as coffee, on a platter perched atop red-checked oilcloth, sat the finest apricot turnovers this side of anywhere.

“Mmm. Succulent orange goo encased in flaky, sugarcoated crust,” ventured Spade, a telecom executive who now lives in Colorado Springs.

“This transcends mere breakfast pastry,” said Dave, his mouth stuffed.

“This is a reason for even jaded coastal dwellers to come to ‘flyover country,’ ” added Steve, a public defender who lives among jaded coastal dwellers in Silver Spring, Maryland.

I didn’t say much. I snarfed three turnovers and later wished I’d pocketed a fourth.

From Kimball, we zigzagged east on Interstate 80, south on U.S. 385, east on I-70, and south on narrow gravel roads toward Mount Sunflower, Kansas. Since all seven of us hail from the Sunflower State, we badly wanted this 4,039-foot trophy.

If you’re not from Kansas, you don’t understand. You tease us with lame Wizard of Oz jokes. (Note: “We’re not in Kansas anymore” is a line from 19-bleeping-39. Let it go.) You find the very concept of Mount SunflowerÔÇöa noble hillock that sits one-tenth of a mile from the Colorado state lineÔÇöto be automatically laughable. But when we were in elementary school, the fact that Mount Sunflower towers above most of Vermont’s Green Mountains was balm to our Kansas souls, like learning to sing the sweet state song, “Home on the Range.”

Mount Sunflower earns a meager 1 on Martin’s scale, involving fewer than ten feet of vertical gain after you park. Non-Kansan eyes might survey the featureless landscape surrounding it and conclude that the nearest town, Weskan, should have stuck with its original name: Monotony. Yet when the Econoline’s doors opened peakside, we saw a dreamscape. Atop a treeless, imperceptible uplift stood a majestic, ten-foot-tall iron sunflower. An American flag waved from its stalk. A small corral surrounded the exhibit, echoing Kansas’s rich cattle-drive heritage.

Highpoint ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°s raves, “Kansas gets our vote for the most creative and whimsical highpoint monument!” We couldn’t have agreed more. State pride engulfed us, despite the moronic entries scrawled in the summit register: “No hiking stick required!” and “It’d be better if you had naked chix!”

WE’D ALL AGREED to fly home from Kansas City on Tuesday. That way, we could highpoint deep into Monday night if necessary. But during the drive from Mount Sunflower to Black Mesa, OklahomaÔÇöa 4,973-footer at the western fringe of the panhandleÔÇöabsentminded Dorrell dropped a bomb. In the parking lot of a convenience store in Lamar, Colorado, he looked at his airline ticket and mumbled, “Uh, guys…my flight’s at 6:20 Monday night.”

Murmur ensued. Followed by hubbub. Succeeded by malice.

Six-twenty on Monday? That was 25 hours away! And we were looking at two or three hours to Black Mesa, at 8.6 miles the longest hike of all. After that there would be 700 miles across the Texas panhandle and Oklahoma before we got to Arkansas and the last summitÔÇönot to mention the final four-hour slog back to K.C.

Our spirits were crushed like the Cool Ranch Doritos fragments littering the Econoline’s floor. We’d have to forget Arkansas or drive all night or both. We’d been slugging it out against the vexing factor of distance, but now that other awful variableÔÇötimeÔÇöhad jumped us from behind and was punching our kidneys.

We rolled up to the Black Mesa trailhead just before sunset. We were tired, grumpy, and about to hike for several hours in the dark. We grabbed three flashlights, two of which worked, and set out across a grassy field studded with scrub pines. We made good time until the trail angled up Black Mesa itself, which is notorious for rattlesnakes. We had to squint at the trail and proceed with caution to make sure nothing was slithering.

Once atop the mesa, we regrouped for the summit push. The markerÔÇöan eight-foot-tall dark-granite obeliskÔÇölooked eerily like the ape-maddening slab in 2001: A Space Odyssey. We fired up our cigars and read on the marker that Texas was 31 miles away, Colorado was 4.7, and New Mexico was but 1,300 feet to the west. Thank goodness the marker didn’t mention the mileage to Arkansas, which would have been depressingly huge.

Hiking down a dark mesa with a lit cigar was a kooky joy, but it had evaporated by the time we reached the van. It was a little after midnight, and mutiny wafted through the air. Casper, the father of an infant son, was especially ready to quitÔÇöhaving skipped his shower in North Dakota, he was desperate for creature comforts.

“Let’s call it six and a memorable weekend,” he moaned. “Let’s get a motel. Showers, clean sheets, sleep, glorious sleep. C’mon …”

Steve, also a father, and Spade, who wanted to watch ESPN to see how his college football bets had turned out, recognized Casper’s patriarchal wisdom and began to cave. Which, frankly, made Drew and me sick. After all this, we were supposed to give up? To tell people that we’d conquered six runts rather than seven, because we couldn’t handle the driving?”

“No way,” I said, though in much coarser language. “Get in the van now! We’re burning daylight standing here! Well, darkness…”

Even though I refused to be stopped, I could see Casper’s point. All of us could. There would be ramifications if we returned to our families and jobs looking like hollow-eyed carcasses. We were 39-year-old men attempting a trip that would exhaust guys half our age. We should be proud enough for bagging six summitsÔÇötwo of which required actual effort. Not to mention the logistical wizardry it took just to get us together in one place.

At the moment, though, that one place happened to be an extremely sad parking lot in the Oklahoma outback. We got in the van and hit the road.

OUR ECONOLINE featured two captain’s seats up front and four bench seats. We had removed the rear bench to make room for luggage, which meant only one guy at a time could catch quality winks by going horizontal.

It wasn’t enough. We needed another sleep bay. After arriving punch-drunk at a truck stop in Amarillo, Texas, I positioned a Therm-a-Rest atop the luggage in the very back. I stretched out on it, not caring how many toothpaste tubes I squished. It was absurdly comfortable. Fresh, rested drivers were suddenly a possibility.

We rocketed east, intercepting dawn near Henryetta, Oklahoma. Then came serendipity: In Fort Smith, Arkansas, we stumbled across a restaurant called Sweet Bay Coffee. We caffeinated until we could caffeinate no more.

From Fort Smith, a series of twisty roads took us up into the Ozark National Forest. After spending so much time navigating open range, the Ozarks’ leafy glades seemed foreign and wrong. Had we really been in North Dakota just two days ago? Our instincts said it couldn’t be possible, though the odometer and our collective stench insisted that it was.

At 2,753 feet, Magazine Mountain was the second-shortest of the Seven Dwarfs but the fourth most difficult, requiring a 20-minute uphill walk. A simple wooden sign marked the top. I touched it. Dave filmed. We sipped bourbon from my flask. And history was made.

Seven up, seven down. As we headed back toward Kansas City, we felt like the heroes we truly were. For about two hours. Then, on U.S. 71 outside Butler, Missouri, we came to a screeching halt behind a long train of barely moving cars.

“Good God,” Dave groaned. “Do these people know who we are and what we’ve done? We’ve been elite road warriors all weekend! But now look at us. We’re just more schlubs stuck in holiday traffic.”

There was no way we’d get Dorrell to the airport in time if we stayed on 71. Our only option was to cross into Kansas and hope that U.S. 69 would take us to K.C. through less traffic.

It worked. Dorrell made his flight; he even had time to take an ineffective sponge bath in the airport loo. The van was returned and Payless Car Rental called me only once to complain about its condition. Dave went back to Santa Monica, where he has yet to begin editing the alleged documentary that brought us to the Great Plains in the first place.

He has, however, found time to compile our statistics. We were out on the road for 86.5 hours. We drove 3,168 miles. We were cited for zero moving violations, though one or two might have occurred. We returned home feeling like mountaineering legends, but as the numbers made clear, the real champ was the Econoline.

“If you do the math,” Dave later wrote us, “you see that, even at the moment we were gorging on apricot turnovers at the Longhorn Cafe, it was still averaging 36.6 miles per hour.”