Sometimes the perfect getaway means returning to the familiar. Five şÚÁĎłÔąĎÍř contributors chose these spots with fond memories in mind, even if those memories involve an uncomfortable jellyfish encounter. Discover these locales for yourself, and you may find your own nostalgic reasons to come back again and again.

Mountain West: Your Own Private Idaho

Southeast: Hurts So Good

Midwest: Hope Sinks Eternal

Southwest: The Price of Freedom

Pacific: Separation Anxiety

: Your Own Private Idaho

Why things are more exciting on the rugged side of the Tetons

We were drifting down the South Fork of the Snake River, the Grand Teton behind us, when my guide began rowing frantically across the stream. This is the telltale sign, of course, that the man on the oars has spied a patch of water that is lousy with trout. He pointed to the left bank. “Cast to the grass,” he said. “Downstream angle, six inches from the edge.” There are times when fly-fishing is all about the tension of waiting—those few seconds after your bug lands on the water, when you enter something like a fugue state of anticipation. This was not one of those times. The moment my size 10 Schroeder’s Hopper lit, the water exploded. Set! Rod tip up! Strip, strip, strip! Just like that, I had a hook-jawed bruiser of a brown trout.

Located 30 miles northwest of Jackson Hole, Wyoming, Idaho’s Teton Valley has all the same outdoor charms, without the Range Rovers, sticker shock, or crowds. It’s also home to a trio of rivers that offer first-rate fly-fishing experiences. The wide South Fork of the Snake is the place to go for monster browns. The pretty, small Teton is renowned for big cutthroats. And the legendary Henrys Fork is arguably the best, and toughest, rainbow fishery on the planet. I’ve also seen shirtless poachers packing out trout in their coolers on the Idaho side. Not everything is manicured and perfect here—which is part of the allure. Not long after landing that trout, I fished a section of the river known as Hollywood, where I got fouled up on my first cast, missed half the run, then lost one of the biggest brownies I’ve ever seen. The bartender down the road ought to thank that fish.

Access: Stay at the (from $260) in Victor. Pick up a license, flies, and a guide at the (guide from $515).

: Hurts So Good

Unplug on a forgotten mid-Atlantic cape. just ignore the jellyfish.

The first time a jellyfish ever slid inside my swimming trunks, I was in Cape Charles, Virginia, at a spot called Pickett’s Harbor, a long beach with sand dunes and a breakwater of sunken ghost ships just offshore. I was six, bobbing around in baggy boardshorts when suddenly my crotch exploded. The pain passed, but my fondness for the place didn’t. My dad grew up in the town of 1,000, about 200 miles southeast of D.C., on the far southern tip of Delmarva, and every summer we’d head “down the road.” We’d put lightning bugs in mason jars, ride bikes down the empty boardwalk with its zero shops, or steam blue crabs we caught at the docks.

Now that I’m a dad, Cape Charles has become my go-to spot, too, though these days there’s much more to do. You can rent a breezy beach house and kayak the Virginia Coast Reserve, a 14-island, 68-mile wonderland of unmolested coastline, marshes, and lagoons. There’s kitesurfing at Sunset Beach and pints at Kelly’s, a pub inside an old brick bank. On most visits, though, I let my world compress to the places I can walk in flip-flops. I find a quiet spot along the town’s half-mile-long beach and watch my four-year-old daughter play in the shallow Chesapeake until her puffy hands are prunes. We eat pizza at Veneto’s and wait for the forests to light up with bug butts. We walk down the boardwalk, which is still miraculously devoid of shops. Maybe one day she’ll feel a connection to this place, too. I just hope hers never stings.

Access: Arrange vacation rentals—and everything from kayak rentals to hang gliding—through .

: Hope Sinks Eternal

There are reasons to fish the same river year after year. Success isn’t one of them.

Each summer, some college friends and I go to Michigan’s Manistee National Forest for a weekend trip we call Fish Yer Briefs Off. The forest has many famous trout streams—the pristine Pere Marquette, the mighty Big and Little Manistee, both renowned for steelhead runs. We don’t go to those rivers. Our place, which I’ve sworn to keep secret, is an hour from Grand Rapids on a forested ridge where a small stream feeds into the bigger river. When the steelhead come in late winter, fishermen line its banks. But we usually go when the forest is empty and the trout are absent.

The first year, we met at a wood-paneled smokehouse off Route 31, picked up steaks and Busch Light, and drove 40 minutes to find that we had nailed the timing. Gray drakes covered the trees, and the sounds of rising trout echoed off the clay banks. We still couldn’t get the fish to take our flies. In 2011, we showed up during the chinook run but had only trout flies. That night a bad windstorm blew in as we were making dinner. Oak leaves circled in dust devils. Birch trees shook like Pentecostals. Then: crrrack! A big oak fell ten feet from our kitchen.

Despite the many mishaps, we always return. We’ve talked about going to the flies-only section on the Pere Marquette, where big trout chase big streamers. We’ve talked about trying the Big Manistee, too. But neither place has our little clearing on a ridge. And I know where I’d rather be.

Access: If you can identify our river, have fun. Otherwise, fish the Little Manistee at the ($14), which has a 1.5-mile trail that connects to the North Country Scenic Trail.

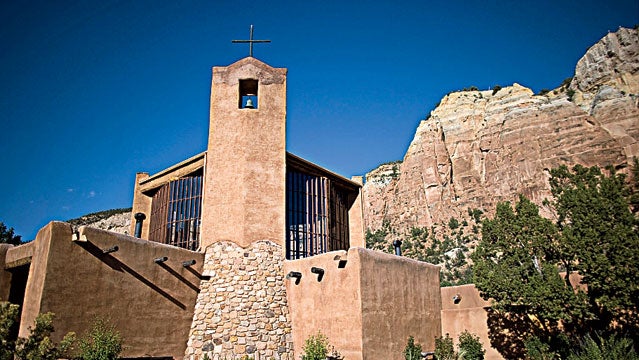

: The Price of Freedom

Learning to raft—at a steep cost—in New Mexico’s finest canyon

The Rio Chama in northern New Mexico—at least the ten-mile stretch that starts near a monastery where the monks brew beer—is not particularly wild. The biggest wave is a Class III roller, and the float ends above a dam that creates the jet-ski haven of Abiquiu Lake. Also, the water often resembles Yoo-Hoo, so the fishing is usually very bad.

Still, the Chama is one of my favorite places on earth for a simple reason: I learned to raft here. I first tried it a few years ago and broke a fly rod or two failing to evade an oncoming cottonwood. But piloting a raft is like skiing or learning an instrument: you do it, and do it, and it makes no sense until, eventually, it does. Eventually happened to me last summer. A friend and I were on a boat with two dogs. This buddy, who used to be a professional kayaker, enjoys offering loud instructions whenever he’s in the vicinity of water. But once we pushed off, I started shifting the oars without thinking, and I heard only minimal advice. I was on autopilot, which is exactly where you want to be on a river as quietly stunning as the Chama. The water may not be pristine, but the surroundings sure are: a series of big, wild sandstone walls, all manner of red and tan. This trip was not entirely successful—another friend drove his pickup over my violin at one of the campsites. (“What was that bump?” “I don’t know, back up!”) I bear no grudge, though. Call it a sacrifice to the monks. Those guys can pick their spots.

Access: Arrange a guided trip through ($105).

: Separation Anxiety

The only thing more difficult than staying dry in Oregon’s rainforest is leaving it behind

My future sister-in-law Alli—we call her Foof—doesn’t belong in southern Oregon. She could easily be a model, lives for electronica concerts, and wants to pursue a career in fashion. She spends many evenings using the Internet in my Ashland apartment to troll Craigslist in Manhattan. Yet she never quite gets up the will to leave—she seems tethered here. I like to think I had something to do with that.

For Foof’s 26th birthday, we took her to the North Umpqua, a Wild and Scenic Class III river in southern Oregon, and rented a cabin above the river. The walls were covered in bald eagle paintings and rusty farm tools. It rained constantly. Despite that, Foof didn’t seem miserable. She put up with me as I yammered on about the delicious kayaking lines down the gin-clear whitewater as we hiked the North Umpqua Trail. Later, she stopped in the rain to admire the brilliant oranges of the changing alders surrounding us. On Sunday, we took a dip at the Umpqua natural hot springs, a series of four travertine pools perched on a cliff, in the company of a gang of survivalist hippies. Foof didn’t blink, just soaked in the 110 degree water and stared blissfully through them at the river below.

About an hour into the drive home, I looked back at Foof. She was staring out the window, smiling, watching the thick rainforest slur by. I thought about how much I was going to miss her when she moved to Williamsburg. Then she said, “I’m so happy I live here.” She still says she’s planning to move away in the fall. I’ll believe it when I see it.

Access: Stay at (from $115), near the 79-mile North Umpqua Trail. Raft with .