IT WAS WEDNESDAY EVENING aboard a ferry bound for Vancouver Island, and although my wife, Kelly, and I had arrived in British Columbia for our clockwise loop around the province just hours earlier, things already seemed a little hinky. INVESTMENT STRATEGY FOR A SOARING LOONIE, read a headline in the National Post (“loonie” referring to the Canadian dollar), but frankly the term might lend itself to a broader application. Everyone we’d encountered so far seemed half a bubble off center. The customs lady at the Vancouver airport confiscated our apples, then sweetly recommended a restaurant in Tofino. The waitress at the Vietnamese pho shop where we stopped for a late lunch looked at me and beamed. “Long time no see!” she chimed.

“Uh . . . yes,” I stammered. I had never set foot in her city before.

Soon after, we drove onto a car ferry larger than some airports, to cross from Vancouver the city to Vancouver the island. Moments after the ship cruised out into the Strait of Georgia, a woman in a corridor on level six unrolled a small mat and nonchalantly performed a perfect headstand, the first I had ever seen done at 15 knots. The moon rose full, looming over a bank of cedars atop one of the Gulf Islands: a perfect circle to launch a circle tour. Then, to our astonishment, a shadow blurred its eight-o’clock edge, the beginnings of what would gradually become a total eclipse. Aha! A possible rationale for irrational behavior: The word lunatic, after all, stems from the Latin lunaticus—moonstruck. Loonies, lunatics, lunar eclipse. The dots began to connect.

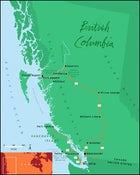

Daftest of all, perhaps, was our own agenda: to try to do justice to the treasures of British Columbia in a mere two weeks. The province’s population is roughly equal to that of Los Angeles—about four million, not counting any post-reelection wave of American lefties—scattered over an area larger than two Californias combined. Its borders encircle thousands of Pacific islands, untamed mountain ranges, pristine lakes and rivers, and ancient rainforests. Sweetening the pot were the creature comforts scattered along our route: hotels and lodges both rustic and indulgent; cuisine flaunting its Pacific Rim provenance and an abundance of local, organic ingredients; spas with an emphatically West Coast tilt. I came to think of B.C. as the Northern Hemisphere’s New Zealand—only three and a half times the size of the original, and not requiring the 12-hour flight.

Our journey’s dotted line would zigzag across Vancouver Island; take us on a voyage through the Inside Passage from Port Hardy to Prince Rupert, far north on the mainland; trace Highway 16 inland, south of Hazelton and through Smithers and Prince George; turn south on Highway 97 through Williams Lake and the Cariboo Country; then wind southwest toward the coast, through Whistler, and back to Vancouver—more than 1,800 miles in all. To recall a saying I learned years ago from a group of people who bungee-jumped out of hot-air balloons: Go big or go home.

Here are a few postcards from the continent’s edge.

Wednesday night

Starting out on the alluring shores of Vancouver Island can be hazardous to a road trip—once nestled there, we were half tempted to scrap the drive altogether. The Brentwood Bay Lodge & Spa, opened last May beside North America’s southernmost fjord, on the Saanich Peninsula north of Victoria, is particularly dangerous in this regard. From the lodge’s marina, you can set out on a dive boat (if the prospect of 48-degree water doesn’t faze you) to explore a colony of glass sponges and some old warships recently imported to the seafloor. Or saddle into a kayak and paddle for hours around the deep-water inlets; the dock of the Butchart Gardens, Victoria’s best-known tourist draw, lies a few minutes away by boat. The in-house spa, taking a cue from nearby vineyards, offers such enticements as the three-hour Vino Ritual, involving various antioxidant grape concoctions (both on the skin and down the gullet), including the Vino Stomp Pedicure. Each of Brentwood Bay’s 33 suites, though, is something of a spa unto itself: With saltwater views, slate fireplaces, king-size platform beds, rice-paper lampshades, exotic bath salts, and jetted tubs, one could do nicely without ever leaving the room.

Thursday and Friday

After a blissful rest, our motivation returned, and so off we steered to Vancouver Island’s west coast—the wilder, more rugged side. Crossing the interior, we gawked at steep, wooded mountainsides rising almost perpendicular from glassy lakes, and narrow waterfalls gushing over roadside cliffs. We arrived in Tofino, a funky end-of-the-pavement outpost surrounded on three sides by water, just as a near-full moon rose and painted the sky sapphire. On the shores of Clayoquot Sound, a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, Tofino has a year-round population of 1,400 or so and a disproportionate number of sea-kayaking and whale-watching outfitters and surf schools (Tofino is ground zero for coldwater surfing in Canada). The local Esso station sells wild rice, mandarin oranges, and even gasoline. One of the best places to eat, SoBo, serves Asian-street-food-style dishes out of a purple catering truck.

“Now even a lot of First Nations kids are getting into surfing,” Dave Pettinger told us. Pettinger owns Pacific Sands Beach Resort, on a crescent of sand along Cox Bay, a prime surf break on the northern edge of Pacific Rim National Park Reserve. He grew up on a dairy farm in Edmonton, where one day in 1973 his parents glimpsed an ad in the newspaper: MOTEL FOR SALE. The “motel” now includes four two-story lodge buildings and six new clusters of luxe two- and three-bedroom villas, with cedar beams, roomy kitchens, fireplaces downstairs and up, and ample amounts of ocean-facing glass. All of the rooms are heated by Pettinger’s latest addition, a geothermal-exchange heating system that employs steady temperatures hundreds of feet underground as a power source.

On Pettinger’s recommendation, we hiked a pair of boardwalk trails that loop through Pacific Rim’s old-growth rainforest—in a torrential downpour. Hoods pulled overhead, we shuffled along like novitiates from some monastery devoted to Gore-Tex. Like anyplace that has remained mostly untouched by humans, the forest has an otherworldly feel, with gardens of moss draped from gnarled branches. Some of the western red cedars are 800 years old, with trunks that would require the combined arm span of five adults to reach around them. Ten feet of annual rainfall waters this garden—a good portion of that, it seemed, during our hike.

Sunday:

A few lessons about Canada gleaned along the road: (1) Kilometers rock! If your rental car measures speed in metric terms, you’ll find it’s far more gratifying going 120 than 75, even if it doesn’t get you there any sooner. (2) Canadian roadsides, for reasons no one could clearly explain, contain virtually no litter. Remarkable. (3) The all-purpose ending to any Canadian sentence—”eh?”—lives on, with regional twists. The Tofino version of adios: “Choo, eh?” On the mainland, among the maniacal mountain bikers we would meet in Williams Lake, more of a nasal hey: “I’m feeling pretty punched, hey?” And the classic, muttered to me by a little hobbit-woman standing in the morning ham-and-eggs line aboard the Queen of Prince Rupert: “Little rough last night, eh?”

We had boarded the boat the previous evening in Port Hardy, on Vancouver Island’s northern tip, for a 15-hour cruise to Prince Rupert, one of B.C.’s northernmost coastal towns, just shy of the Alaska panhandle. As the ferry chugged into the exposed waters of Queen Charlotte Sound, unprotected from Pacific storm swells, we sat in the dining room and watched the wine in our carafe begin to pitch and yaw, my stomach soon following suit. Happily, the seas calmed once the ship entered the sheltered channel of the passage. After overnighting in a small cabin, we had Sunday breakfast while watching spotted humpback whales spouting on the horizon. At noon, porpoises arced in circles to starboard. Gulls raced alongside the ship like farm dogs chasing a pickup truck. Now and then we passed tugboats pulling log-piled barges, lonesome logging camps, a floatplane. It was a peaceful day’s idyll, at an almost forgotten pace.

Monday

We slowly headed east on Highway 16, also known as the Yellowhead Highway, out of Prince Rupert—a bustling little port city with dozens of First Nations totem poles—and Port Edward. Fishing and whale-watching boats angled across the bay, leaving trails of foam like comet tails. At the fishermen’s memorial, overlooking the mainland and other islands, engraved plaques list the names of those lost at sea. Not far out of town, the road began tracking upstream along the Skeena River, choppy and as wide as a lake at first, then shallower, meandering around broad gravel bars and wooded islets. We crossed dozens of creeks and rivulets and passed more waterfalls than we could count, spilling over cliffs hung with thick patches of moss.

By evening we’d arrived at the Minette Bay Lodge, a remote but highly civilized inn with seven guest rooms. Kayaks and canoes lay in wait near the waterline, but the main reason guests pilgrimage here is to board helicopters on its broad lawn and then hover off to the surrounding wilderness to decide which trout or salmon hole—in some 20 entire rivers—they would like to fish all by themselves that day. Minette Bay’s English-born proprietors, Dr. Howard Mills, a physician who practices in Kitimat, and his wife, Ruth, both spent time in Africa as youths and have done their share of globe-trotting. The lodge’s walls and shelves are festooned with carved native masks, photographs of sailboats, a Bible from the 1500s, antique foxhunt prints, nautical charts and maps, a World War I periscope, and a two-foot-long replica of a wild boar from New Guinea trimmed with cassowary feathers. After a day’s fishing, guests swap stories around a broad Scotch-pine dining table.

Wednesday

We arrived at the Logpile Lodge, on a rocky knoll outside Smithers, farther inland on the Yellowhead Highway. This is a lively town of 5,500, but it still has an undiscovered feel, as if you’ve time-traveled into Boulder, Colorado, in the 1960s. “There’s tons of people here who really chose the place not for economic reasons but because of lifestyle,” said Christoph Luther, who came from Switzerland with his wife, Barbara, then built the seven-room lodge, with its massive spruce and pine logs, eight years ago. Wooden skis lean against the dining-room fireplace. Hudson Bay Mountain, 7,648 feet high, towers outside the front door. Other émigrés have come to Smithers from Vancouver, Quebec, Europe, even China and Vietnam.

Not long after you arrive in town, someone will likely repeat to you the truism that Smithers has a higher percentage of Ph.D.’s than anywhere else in western Canada. The main draw is not just a dazzling menu of adventure-sports venues—hiking in Babine Mountains Provincial Park; whitewater on the Skeena, the Bulkley, and other rivers; climbing on Mount Rocher DeBoule; and skiing in the Telkwa and Howson ranges—but also the solitude. “You don’t see another person here!” Barbara said. “It’s always said Smithers is the best-kept secret. Sometimes too well kept.”

Friday morning

Heading south on Highway 97, we neared the town of Williams Lake, in the heart of Cariboo Country, a district of rolling rangeland, evergreen hills, and lakes between the Coast Mountains and the Rockies. The Cariboo Gold Rush of the 1850s and ’60s spawned tales of claim jumping and hanging judges, with fresh stories in the making: There are still men here who live on their gold claims, with only a woodstove and a dog for company. We overnighted at Tyee Lake Resort, a restful 15-room lodge on a four-mile-long lake. Guests arrive to fly-fish for kokanee and trout, to honeymoon, to swim in the lake, to uncoil. Our hostess, Kim Burgoyne, regaled us with some half-mad stories of her own, including one about the lodge’s ill-fated first attempt to offer dogsled rides in the winter, in which a local musher named Guy (who had once extracted all of his own teeth with a pair of pliers) brought a team consisting of a bitch in heat and several highly agitated males. Not a good idea.

Saturday afternoon

We drove less than an hour to Williams Lake. Starting in the mid-nineties, this town, best known as the site of a summer rodeo, has become popular for freeriding, a style of mountain biking tailored to fearless thrill chasers and stark raving nut jobs (with a good deal of overlap). Standard equipment includes body armor and bulky 30- to 40-pound full-suspension bikes designed for stability, for riders who are arguably not designed for stability. “You could fill a garbage truck with all the frames that get broke in this town,” said Merle McAssey, co-owner of Adrenalin Mountain ���ϳԹ���s, a touring company at the heart of the tight-knit local cult of riders. In the past year, Merle has racked up an anatomically improbable four broken collarbones. “A right, then a left, then both at the same time,” he explained cheerfully over dinner at the Overlander Hotel. “We all have the same surgeon.”

Earlier, we had ventured out on a ride with half a dozen local hardcores down a fir-wooded slope on the edge of town, along a trail called Mitch’s Brew. (Mitch himself didn’t come; he’d recently had a titanium rod inserted into his leg.) Threading through the trees like hummingbirds, we paused to watch members of the group launch furious aerials off a wooden trestle that ended abruptly, 15 feet above the ground, like a Salvador Dalí bridge, and ramps, assembled from logs and planks, that emptied onto 30 feet of uninterrupted air. The riders seemed motivated not by machismo but by raw exuberance, tracing tightrope lines down slick fallen logs, whooping and egging one another on. “Feeling pretty punched, hey?” “Pure, total commitment, hey?”

During the ride, we had assumed that these were likely the sort of people who don’t bother holding down steady jobs, who sleep on friends’ couches to save up for more gear, who subsist on ramen noodles. But over dinner, we learned that the gonzo crew in fact consisted of a pharmacist, a pair of engineers, an industrial electrician, and, appropriately, a trauma nurse. During the previous week’s lunar eclipse, 14 riders had donned headlamps and set out on a moonlight descent down Desous Mountain, a local freeriding hot spot, performing drops and jumps and launches until midnight. “I think the philosophy for us,” Merle said, “is to expand people’s notions of what’s possible.” Soaring loonies, indeed.

The BC Circle Tour

A complete provincial sampler, stop by stop

Getting to the starting point in Vancouver is easy. Several airlines fly there daily from many U.S. cities. Alternately, drive north from Seattle on Interstate 5, which becomes Highway 99 in Canada, or ferry directly to Victoria from Seattle (Victoria Clipper; 800-888-2535, ).

Word to the wise: Throughout B.C., there are often vast expanses between towns, with few or no facilities. Fuel up—your car and yourself—whenever you have the opportunity.

STOP ONE: Reserve a space on the ferry from Tsawwassen, about a 40-minute drive south of Vancouver’s airport via Routes 99 and 17, to Swartz Bay, on Vancouver Island (fares and schedules, 250-386-3431, ). Driving south on Highway 17 toward Victoria, follow signs to Brentwood Bay Lodge & Spa (doubles from $367, including breakfast; 888-544-2079, ). Rent a kayak at the lodge’s marina ($34 per day for a single, $51 for doubles) and float around glassy Saanich Inlet, mingling with seals, orcas, and bald eagles.

STOP TWO: From Victoria, go north on Highway 1 (it becomes Highway 19 in Nanaimo), then west across the island on Highway 4 to Tofino—about 200 miles total. After crossing Pacific Rim National Park Reserve, check in at Pacific Sands Beach Resort, a welcoming family-run lodge on Cox Bay (doubles from $143, villas from $2,946 per week; 800-565-2322, ). The next day, take a two-hour Zodiac ride to Hot Springs Cove, where 105-degree sulfur-spring water tumbles down terraced pools into Clayoquot Sound ($84–$93 for a seven-hour trip; Remote Passages Marine Excursions, 800-666-9833, ).

STOP THREE: Backtrack east across the island, then head to its northern end to catch the ferry at Port Hardy, a long day’s drive of 300-plus miles (May 18 through September 30, ferries depart at 7:30 a.m. and arrive at Prince Rupert, 273 nautical miles north, at 10:30 p.m.; rates and schedules, 250-386-3431, ). In Prince Rupert, request a harbor-view room at the Crest Hotel (doubles from $124; 800-663-8150, ). The next day, book a boat tour with a native Tsimshian guide to the Khutzeymateen Valley, a dense rainforest and site of Canada’s only grizzly sanctuary ($124 for six hours; 250-624-5645, ).

STOP FOUR: Heading east on Highway 16 out of Prince Rupert, take a side jaunt at Port Edward to the North Pacific Cannery, a time-warp Steinbeckian remnant of the hundreds of salmon canneries that once dotted the West Coast. At Terrace, turn south on Highway 37, following signs near Kitimat to Minette Bay Lodge (about 150 miles total). This cozy seven-room haven, built in 1995, boasts feather beds and arguably the best showers on the continent (doubles, $168, including breakfast, with heli-fly-fishing packages starting at $4,394 per person for four days; 250-632-2907, ). Fly-fishing is the ticket here, on salmon and steelhead streams in the heart of untrammeled Coast Mountains wilderness; the lodge’s staff can also arrange hiking (with or without helicopter) and kayak tours.

STOP FIVE: Retrace your route back to Terrace and continue east on the Yellowhead Highway about 180 miles to Smithers, stopping en route at Hazelton, a vintage riverboat town that suggests a Far North version of Mark Twain’s Hannibal. In the woods outside Smithers sits the Logpile Lodge, a seven-room spruce-wood warren of charmingly rustic rooms, complete with furniture built by Christoph Luther, the lodge’s co-owner (doubles from $84, including breakfast; 250-847-5152, ). For a taste of the backcountry, hike the 4.3-mile Silver King Basin Trail, in Babine Mountains Provincial Park—some 80,000 acres of soaring peaks, glacial lakes, and subalpine meadows a ten-minute drive from the lodge. Mountain goats, moose, and the occasional grizzly have been known to appear.

STOP SIX: Continue east about 240 miles to Prince George, B.C.’s fourth-largest city, in a bowl that once held an enormous glacial lake. Book a room at Esther’s Inn, an outpost of northern kitsch with a poolside indoor jungle and a well-stocked bar (doubles from $57; 800-663-6844, ). While in town, hike a portion of the 15-mile Cranbrook Hill Greenway, a network of hiking and cycling paths that thread through a forest of birch, cottonwood, spruce, and hemlock.

STOP SEVEN: Drive south 140 miles on Highway 97 to Tyee Lake Resort, near McLeese Lake, a 15-room fishing lodge in the heart of rugged Cariboo Country (lake-view doubles, $117, including breakfast and use of boats; 866-989-9850, ). Fly-fishing is the local passion, and there are hundreds of uncrowded trout- and kokanee-stocked lakes within a short radius; the Osprey Restaurant offers Indonesian tenderloin, spicy “gunpowder” prawns, and other exotic fare. About an hour south, in the town of Williams Lake, hook up with the crew at Adrenalin Mountain ���ϳԹ���s for a day of guided biking on some of the more than 100 trails around town, tailored to your levels of skill and ballsiness ($94; multi-day tours also available; 250-392-6299, ).

STOP EIGHT: Take Highway 97 south and then 99 southwest on a 275-mile leg through the mountains to Whistler, darling of skiers and co-host (with Vancouver) of the 2010 Winter Olympics. By now you’ve earned a little hedonism; spring for a room at the new Four Seasons Resort Whistler, where the beautifully appointed rooms feature balconies, gas fireplaces, and amply proportioned bathtubs (doubles from $206; 800-819-5053, ). Downstairs, the Fifty Two 80 Bistro hosts a nightly orgy of fresh-caught seafood, a great wine list, and attentive service. Whistler has plenty of summertime playgrounds, including some serious whitewater runs; Whistler River ���ϳԹ���s offers day trips through the canyons and waterfalls of the Elaho and Squamish rivers, among other packages, for $130 a person (888-932-3532, ).

STOP NINE: End your journey with an exclamation point by taking the Sea to Sky Highway 76 miles—through a gorgeous backdrop of granite cliffs, waterfalls, and hazy island vistas—to Vancouver.

The New American Dream Towns

Smart Urban Ideas, PT III: Tucson, AZ, and NYC

Smart Idea #8

• Tucson, Arizona

In this Sonoran Desert city of 528,000, WATER CONSERVATION is considered a civic duty. Thanks to creative incentives (like increased rates for overconsumption and PR campaigns to encourage wise use), the average Tucson resident uses 120 gallons of water per day—slightly more than half what Phoenix locals use. And residents of the nonprofit Milagro Cohousing, a neighborhood of 28 sustainable adobe homes built around a common space, are going one step further: harvesting storm water in basins to irrigate their landscaping and treating wastewater to irrigate fruit trees and a hummingbird garden.

—M. M.

Smart Idea #9

• New York, New York

New York City has always been a model for mass transit—seven million use the system per day—but now it has even more reason to brag. This fall, construction begins in Manhattan on an estimated $65-million-to-$100-million project to convert a weedy 22-block stretch of elevated railway into an URBAN OASIS of native grasses, wildflowers, and shade trees. Dubbed the High Line, the public garden has already generated plenty of buzz, thanks to a MoMA exhibit of design plans and photographs that runs through October, as well as celebrity hype from actors Edward Norton and Kevin Bacon.

—M. M.