Most of Mother Nature’s most spectacular shows are all about being at the right place at the right time. Maybe you waited your whole life to witness a total solar eclipse, or perhaps on your last mountain trek you stumbled upon a radial rainbow cloud with your own shadow as the star. In all cases, natural phenomena are a reminder that science has the power to leave us more in awe than any sci-fi show possibly could.

Some phenomena are more well-known than others, though, and some are harder to catch. You’ve probably heard of the aurora borealis, or northern lights, and bioluminescent bays, but what about sailing stones and glow-in-the-dark mushrooms?

From Antarctica’s mysterious Blood Falls to Yosemite’s fleeting Firefall, here are some particularly unique natural phenomena that you can’t find just anywhere.

Hokkaido’s Frost Flowers

In winter on Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost island, even as temperatures in Akan-Mashu National Park drop to minus 4 degrees Fahrenheit, Lake Akan is seemingly abloom with life in the form of an endless ethereal meadow of ice flowers. These beautiful blooms on the lake’s surface, known as frost flowers, sprout when the temperature drops quickly, causing a drastic difference between the cold air and the warmer ice surface. When the mist in the air freezes and hits the ice, it gets crystallized. The ice crystal patches are piled in layers and form delicate patterns, looking like real flower petals. Meteorologists have found that this is most likely to occur when three conditions are met: the surface of the lake is frozen with a thin, clear layer of ice and no snow; the air temperature is below 5 degrees; and there’s no wind.

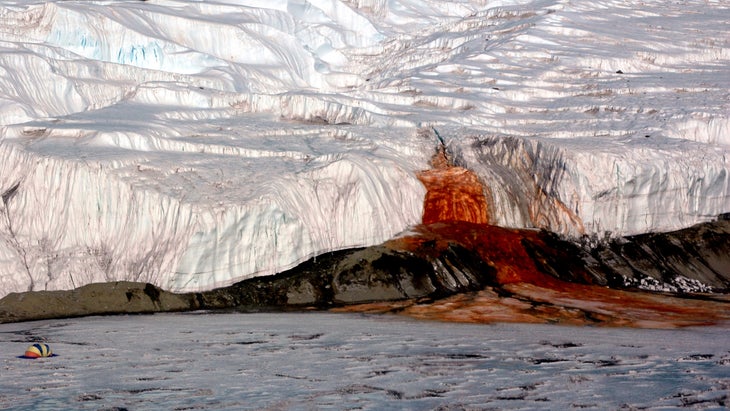

Antarctica’s Blood Falls

It sounds like the next Netflix thriller and might look as ghastly, but East Antarctica’s Blood Falls is only gushing saltwater. This dramatic piercing on the white continent oozes five stories high at the end of Taylor Glacier, where an ancient saltwater reservoir trapped beneath the glacier flows to the surface and into Lake Bonney. The buried saltwater lake is not actually red—nor is it full of red algae, as once believed—but it is super salty and rich in iron. The iron turns red when it reacts with the oxygen at the surface, and its high salt content prevents it from freezing, according to . That’s how eery red water ends up flowing out of the icy white glacier.

Brazil’s Bioluminescent Mushrooms

You may have already been lucky enough to see ocean water sparkling at night with millions of glowing phytoplankton—a phenomenon called bioluminescence, in which living organisms emit a cold visible light. But did you know there are glow-in-the-dark mushrooms? Brazil’s Atlantic Forest, teeming with biodiversity as impressive and unique as its larger Amazon rainforest, contains about 20 species of bioluminescent fungi. These mushrooms flourish in the humidity and grow on tree bark or on tree trunks and fallen branches that line the forest floor. By day you wouldn’t take a second glance at these tiny mushrooms, but at night these fungi glow due to a chemical reaction between them and the decaying wood on which they grow. Scientists only recently discovered why this happens: the fungi produce light that will then help spread their spores throughout the forest. , a protected reserve used for research and conservation in the Atlantic Forest, offers guided night tours to see the bioluminescent mushrooms.

Yosemite’s Firefall

For just a few weeks in mid-February, thousands flock to Yosemite National Park to view this optical illusion on Horsetail Fall, a small waterfall on the famed rock face of El Capitan. A fleeting flow of fire-like light emits for just a few minutes when the alignment of the sun, the waterfall, and the viewer are just right. Right before sunset, if there is enough water, Horsetail Fall will be struck by the fading sunlight in such a way that a streak of fiery orange appears, resembling a lava flow on the 3,200-foot monolith. This completely natural event is actually named after a manmade tradition that started back in 1872, when the owners of the Glacier Point Hotel threw a bonfire off the edge of the waterfall to dazzle onlookers. The park put an end to the dangerous show in 1968, but five years later, climber and photographer Galen Rowell snapped Mother Nature creating the same effect, bringing the optical illusion to the spotlight and reviving the Firefall tradition in a safer way.

High Altitude’s Brocken Spectre

It sounds like a German punk rock band name, but Brocken spectre is a trick of the light that puts you on center stage. This optical illusion is named after Brocken, the highest peak in Germany’s Harz Mountains, where it was first observed. In the cloud-shrouded Chinese mountains of Huanshan and Mount Ernei, it’s referred to as Buddha’s light. Also known as mountain spectre, it occurs at high altitudes under misty conditions when the observer’s shadow is magnified and cast upon the clouds opposite the sun. As a result, the shadow appears surrounded by a spectacular rainbow halo caused by the diffraction of light. The Scottish Highlands’ misty weather and high peaks are a frequent setting for this phenomenon. It’s also been documented on in Washington’s Olympic National Park.

Death Valley’s Sailing Stones

On the dry lakebed of Racetrack Playa, in a remote valley between Cottonwood and the Last Chance Ranges, rocks sail across the desert floor propelled by a mysterious power. While no one has documented seeing them move in person, the tracks left behind the stones and the changes in their location prove they are indeed moving. Some trails left behind extend as long as 1,500 feet. In 2014, a helped scientists determine the sailing stones were likely due to a perfect combination of ice, water, and wind. That’s right—ice in Death Valley. “I’m amazed by the irony of it all,” after solving the mystery. “In a place where rainfall averages two inches a year, rocks are being shoved around by mechanisms typically seen in arctic climes.”

Alberta’s Frozen Methane Lake Bubbles

In winter months, Abraham Lake in Alberta, Canada, is known for a peculiar marvel that lies beneath the surface of its clear blue frozen water. Throughout the year, Abraham Lake, also the largest reservoir in the province, emits methane gas when bacteria feed on decaying plants as part of a natural biological process. During winter, when temperatures drop below zero, these large amounts of methane gas form bubbles that are trapped in the ice as they rise to colder water closer to the surface. What results is a beautiful effect of cascading white orbs with an ominous core. Inside these bubbles is methane, a highly flammable greenhouse gas more than and therefore much more of a threat to our climate as well.