OTHER COUNTRIES MAY HAVE S.A.D. (seasonal affective disorder), which plunges people into dark depression, but Iceland has the opposite affliction: summer activity delirium, a Nordic outdoor madness that runs from June through August and sends locals, who have hibernated during the long cold winter, heading for the glacialrivers and volcanic hills to enjoy all-night kayaking, salmon fishing, off-trail hiking, and river rafting under the midnight sun.

Iceland ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° Guide

║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° has joined forces with Away.com to provide you with the very best that the North Atlantic isle has to offer. Explore the infinite possibilities for unconventional adventures—hike Europe’s largest glacier, trek across lava fields, canoe through volcanic landscapes—and . Viking showers: one of Iceland’s many waterfalls.

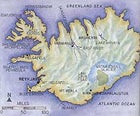

Viking showers: one of Iceland’s many waterfalls. Map by Jane Shasky

Map by Jane Shasky

Summer madness also encourages indigenous activities that are so kooky they could be espoused only by Iceland, the sparsely populated, snowed-over landmass in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean whose inhabitants lived in virtual isolation for 800 years. There’s spranga, for example, which involves performing aerial flips and gymnastic turns while swinging from a thin knotted rope attached to a vertiginous sea cliff, a sport that evolved from the methods the Vikings once used to hunt birds in their coastal nests. Andwatercross, a contest that happens every year around the northern oasis of Lake M├Żyvatn, east of Akureyri, in which the winner is the snowmobile driver who executes the most aquatic laps without drowning his Polaris in the drink. Or Arctic rafting, in which teams lug rubber whitewater rafts up sharp snowy peaks and careen down the flanks.

But my favorite all-night rite of summer is the puffin rescue, an event that takes place every August in the south of Iceland on the tiny island of Heimaey, where millions of birds live and breed. I kept asking about it in Reykjav├şk, but nobody seemed to know what I was talking about. Then one summer I met shoe magnate Oskar Alex Oskarsson, who’s from Heimaey, and he sent me to the island to run ragged at twilight with his mother and her grandchildren. During the day, they toured me around and pointed out the places where thousands of nocturnal baby pufflings emerge from their nests in the cliffs and fly out to sea in search of food. The problem is that, every night, several thousand of the confused little critters, attracted to the blinking lights of town, fly away from the ocean and alight under streetlamps. Enter the town’s 5,000 citizens, who don’t sleep the entire month of August because they’re out all night running after birds.

This is harder than it sounds. We were out from midnight until 4 a.m. chasing after fluffballs the size of runt kittens, cornering them in teams of three or more in parking lots and soccer fields, and storing them in shoe boxes.

We then went home and napped until 6 a.m., when we drove to the beach cliffs and extracted the chicks, whose chirps were emanating from the shoe boxes, and flung them out to sea.

Icelanders├ş symptoms of summer activity delirium are endless. You too can get in on the madness, but when planning your own expedition to the country’s spectacular volcanoes and glaciers, know this:

(1) The weather can go Arctic on you even in summer: Last year on a relatively easy 25-mile trek from P├│rsm├Ârk to Landmannalaugar, an American man died of hypothermia because he lacked raingear. So get advice from locals if you plan to venture out on your own.

(2) Whatever you dream of, someone will help you: When I fessed up to Einar Finnsson, one of the crack mountain rescuers who started Ice-landic Mountain Guides adventure tours, that I was harboring fantasies of spending two months walking the country’s 900-mile Ring road, he didn’t think I was crazy. Instead, he suggested something more ambitious: taking six months and hiking along the off-trail south shore and north fjords as well. He even said he’d map it for me.

(3) All the possibilities for unconventional adventure can make Iceland addictive: On my latest trip here, an immigration official at the Keflav├şk Airport flipped through my passport and said, “I can see you’ve been here six times. By the time you come back, you’d better be able to speak Icelandic.” His comments amused me not because he thought I should take up a new language, but because he was so absolutely sure I’d be back—and soon.

Access and Resources: Reenact Your Own Viking Saga

The Western Fjords.

The Western Fjords.Trekking the Laki Lava Field // Southern Iceland

When Iceland├şs Laki volcano last let loose (in 1783), it spewed 30 billion tons of lava and ripped a 15-and-a-half-mile-long fissure across the landscape, making it one of the largest eruptions in human history. It’s not likely to blow again any time soon, but a trek across and into the 135 craters it left behind gives a glimpse of its awesome power. If you explore the terrain with Icelandic Mountain Guides, you’ll be hiking six to eight hours a day, starting at the old farming community of Kirkjub├Žjarklaustur (don’t even try to pronounce it)—where the lava miraculously halted at the town church—past abandoned farms where you’ll camp for the night, through wetlands chiming with birdsong, and into the 226-square-mile lava field with craters so imposing some of them merit their own names, such as Red Hill. It’s no wonder this striking Arctic desert geormorphology was where Neil Armstrong trained before he set off on the first Apollo mission to the moon. Reykjav├şk-based Icelandic Mountain Guides (011-354-587-9999; ) offers five-day guided trips here for $340.

Paddling Breidafj├Ârdur Archipelago // West Coast of Iceland

The subarctic archipelago of Breidafj├Ârdur, a wild maze of almost 2,700 tiny, mostly uninhabited islands, is Iceland’s only marine conservation area, which makes it perfect for sea kayakers who want to avoid the country’s otherwise ubiquitous coastal commercial fishing boats. The spectacular western coast is also home to thousands of cormorants and shags that breed on the offshore islands. Starting from the isolated coast at Dagverdarnes, you can paddle past Helgafell (a holy hill—not the volcano south of Reykjav├şk—mentioned in the Icelandic sagas as a territory that sparked a blood feud) and other mountains of the Sn3/4fellsnes Peninsula, through skerries that jut out of the water like an offshore Stonehenge, and among island colonies of friendly seals. Most paddlers who go on the four-day trip offered by Ultima Thule are intermediate kayakers ($390; 011-354-567-8978; ).

Backpacking the West Fjords // Northwestern Iceland

Visitors may think Iceland is sparsely populated, with just 281,000 people living on 39,709 square miles (a landmass roughly the size of England, which is home to 48 million people), but when the locals need space, they head north to the 232-square-mile Hornstrandir nature reserve, stunningly wild terrain near the Arctic Circle. The handful of farmers who once lived here fled in the 1950s, unable to bear the isolation. Con-sequently, there are no roads, so you can either walk in (which takes four or five days from the nearest village, Nordurfj├Ârdur), or take the ferry from ├Źsafj├Ârdur, the central hub of the West Fjords. Most backpackers opt for the ferry ride to the abandoned hamlet of Hornv├şk. From here you can climb K‡lfatindar, at 1,760 feet the highest cliff around, which has an incredible view of the Greenland Sea and the Hornbjarg nesting grounds crowded with razorbills, puffins, and fulmars. Then hike along the uninhabited coast across rock fields, shallow rivers, hidden coves, and meadows bursting with flowers. The 20-mile trek ends at Adalv├şk, another abandoned homestead, where you catch the boat back to civilization. Be forewarned: It’s so remote that even the powerful Icelandic cell phones that work in the glacial interior don’t get signals here. ├Źsafj├Ârdur-based West Tours (011-354-456-5111; ) offers five-day walking excursions for $480, including food, guides, and luggage transport. Hornstrandir Tours (011-354-895-1190; ) can assist hikers in planning their own expeditions and has two boats that drop off and pick up backpackers.

Access and Resources: Reenact Your Own Viking Saga

The diminutive yet durable Icelandic horse.

The diminutive yet durable Icelandic horse.Whitewater Rafting // North Iceland

Whitewater rafting may be a relatively new activity in Iceland, but if you want to tackle the country’s toughest waterways, act now. Within the next few years, Iceland’s government plans to dam up the rivers of the northern Skagafj├Ârdur coast, considered the country’s top rafting area, to power a hydroelectric plant. Icelanders prefer the wild of the East River (J├Âkuls‡ Austari), a ten-mile run through deep basalt gorges, under red cliffs, past black sand beaches, and through dramatic Class IV rapids. Based at Varmahl├şd in northern Iceland, Activity Tours (011-354-453-8383; ) offers three-day trips on the East River ($430, not including travel from Reykjav├şk).

The Viking Horse // Near Reykjav├şk

Only 13 hands high with long shaggy manes, Iceland’s friendly horses appear to be dainty little ponies, but the diminutive beasts are actually tougher than the volcanic rocks they clamber over. They’re also accustomed to carrying much heavier loads than pampered American stallions, which may ex-plain why former heavyweight-boxing-champion-turned-horse-lover George Foreman, who owns nine, has such an affinity for them. But the most popular feature of these purebreeds is that even someone who’s never been on a horse before can learn to handle one in five minutes, and then spend the next few hours in a “tolt,” the horse’s signature fast but smooth gait. First-timers might want to start off with a three-hour Lava Tour ($44) or a four-hour Viking Express adventure ($60) through lava fields around 1,122-foot Mount Helgafell volcano near Reykjav├şk, offered by the Ishestar Riding Center (011-354-555-7000; ). Ishestar also organizes a seven-day, 145-mile trek ($1,536) across Iceland on the Kj├Âlur Trail for hard-core equestrians. This ancient Viking route will take you past national parks, monumental waterfalls, glacial rivers, geothermal hot springs, and lush valleys. —N.S.

Getting There // Iceland

Because Iceland’s long sunny nights allow for nonstop adventure, summer is the best time to visit, but it’s also the busiest and most expensive season, so plan ahead. Icelandair flies daily to Reyjkav├şk from New York, Boston, Minneapolis, and Baltimore (summer round-trips from $982; 800-223-5500; ). But last-minute deals are available via Icelandair’s affiliated Web site (), which offers good rates on flight-plus-hotel packages. The Icelandic Tourist Board () gives advice on hotels and tour operators, and pointers on everything from horseback riding to saltwater angling, plus information on special summer events, like the Arctic Open golf tournament and the Reykjav├şk Marathon. —N.S.

Mars on Ice

Exploring Europe’s Largest Glacier

I WAS ON EDGE of the Vatnaj├Âkull Glacier in a modified monster truck staring out at fog as thick as our driver Addi’s Icelandic accent. I was here with a volcanologist, Haraldur Sigurdsson, to hut-hop and explore the geothermal vents and volcanic craters of the 3,247-square-mile Vatnaj├Âkull—the largest glacier in Europe. But instead of tackling our planned 100-mile route on skis, we hired a “super jeep.” This tricked-out Toyota Land Cruiser came equipped with two steel ladders for bridging crevasses, and giant knobby tires deflated to a flabby three psi to plow through snow up to three feet deep.

WE BUMPED ALONG THE ICE, surfed through deep drifts, and used the ladders to crawl over crevasses. But we were oblivious to the dangers outside the vehicle, thanks to Dire Straits blaring from the CD player and the built-in GPS device charting our course. Four hours and 40 miles later, we reached the rim of Gr├şmsv├Âtn caldera, where an elaborate cave system carved by geo-thermal vents stretches for miles below the glacier. We rappelled into the caldera, then hacked our way back up the soft ice of a 70-degree couloir bordered by columns of black volcanic ash. The next day, we used crampons and ice axes to down-climb through a deep crevasse at the lip of the caldera into the slippery ice passages of Vatnaj├Âkull’s underworld. At night, we sipped cold beers and relaxed in the geothermally heated sauna next to the Gr├şmsv├Âtn Hut, one of the Iceland Glaciological Society’s half-dozen widely spaced cabins scattered at points across the glacier.

THREE DAYS LATER, we set out for the far northern end of the Vatnaj├Âkull, 25 miles away, to explore Kverkfj├Âll volcano. When we arrived, we dropped our packs at the nearby Kverkfj├Âll Hut, a ten-by-ten-foot wooden box, and walked to the edge of the half-mile-long crater. Mud pits littered the floor of the chasm, while sulphur bubbled and dozens of smaller vents hissed scalding-hot steam. After pounding several pitons into the soft lava rock, we made an easy rappel into this 200-foot-deep Martian landscape. The ground beneath me trembled with volcanic force, and suddenly Kverkfj├Âll sent forth a geyser of boiling mud 50 feet from where I stood. Simultaneously, a block of blue ice calved from the overhanging glacier—a frightening reminder that life is never static in the land of fire and ice. —Mark Synnott

The Icelandic Glaciological Society has six huts spaced 30 to 50 miles apart on the glacier. (If you are skiing, plan on tent bivvies to bridge the distance.) The huts cost $20 per person per night. For information on the huts or super-jeep tours ($400 per day, accommodations extra), call Icelandic ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°s (011-354-569-1000; ).

Hot-Pot Luck

Tubing Your Way Around the World

Blowing off steam in one of Iceland’s hot springs.

Blowing off steam in one of Iceland’s hot springs.THERE IS NOTING LIKE dunking your body in 102-degree water while your head periscopes up through the steam into 48-degree mountain air. In fact, this Icelandic tradition of lolling in mineral-rich geothermal runoff, which gets its blistering temperature from subterranean volcanic activity, dates back at least a thousand years. Today’s Icelanders use the “hot pots” as places to gossip, detox, and, pun intended, let off steam. Politicians and executives conduct business in the pools, and the country’s daily paper Morgunbladid runs a gossip column titled “Overheard in the Hot Pots.”

THE APEX OF THE HOT-POT SCENE is Iceland’s famous Blue Lagoon, 53,820 square feet of opalescent turquoise waters surrounded by craggy black lava hillocks. The water’s surreal hue comes from a combination of blue-green algae and soft white silica mud that forms on the rocky bottom. Forty minutes from Reykjav├şk, the Blue Lagoon is open year-round (entrance fee $8; 011-354-420-8800; ).

BUT FOR A TRUE ICELAND EXPERIENCE, try one of the downtown pools run by Spa City (entrance fee $2; ). The Laugardalslaug (011-354-553-4039) is an old favorite, with its steam baths, three hot pots, and a stone-walled whirlpool. The city├şs newest, Arbaerjarlaug (011-354-510-7600), has pools with jet-massage seats, mini-geysers, and water slides. But don’t forget to shower nude before you put your suit on and jump in, or you’ll get chastised by vigilant locals for whom the baths are a sacred ritual. “Geothermal bathing is good for your heart,” says Grimur S3/4mundsen, the Blue Lagoon’s managing director. “It’s good for your social life too—you never know who you might meet there.”