WAS IT A VISION or a waking dream? I stood stranded in a ludicrously steep, boulder-strewn gully on a 3,000-foot rock pile called Mount Keen, in a state of physical distress that had moved beyond discomfort and infirmity, past complaint, through muttering and disorientation to a detached state of surrender. The sun beat down.

Wax Highlander

A wax Highlander at Glenfinnan Monument

A wax Highlander at Glenfinnan MonumentHighland cows

Highland cows near Kingussie

Highland cows near KingussieGlen Avon

Glen Avon

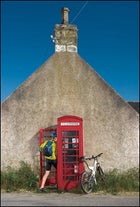

Glen AvonFulton

Fulton (center) at Glenshield Lodge

Fulton (center) at Glenshield LodgeI was on the fifth day of a six-day coast-to-coast journey by mountain bike across the deceptively charming Scottish Highlands, a course originating at the Sea of the Hebrides, on the west coast, and wending its way over 220 miles of temperamental terrain toward the rumored North Sea. At the moment, I was no longer on my bike; it was on me, slung over my shoulders. Although I had, earlier in the week, grappled with a hint of hypothermia, a suggestion of sunstroke, numerous intimacies with mud, bramble, running water, and rock, and an ever-shifting array of orthopedic deficits, my most woeful moment was now upon me.

I had set out that morning after a sleepless night, having immoderately sampled the local offerings of haggis, black pudding, and other shadowy offal┬Śtreats chased down with a splash or three of the spirits for which the Highlands are justly famous. This day, touted as the most challenging of the trip, had started gently enough, climbing through a patch of remnant Caledonian forest, winding through open meadows infused with a dozen shades of green, following a disused “drove road,” or cattle trail, along a meandering tributary of the River Dee, pausing for breath at the stone ruins of an ancient shepherd’s hostel. But these splendors were all but lost on me. By the time I reached the base of Mount Keen, I was in the clutches of dehydration, legs wilted and head throbbing. My fellow riders, all a good deal more dedicated to the ideology of mountain biking than I┬Śand therefore more prone to exult in suffering┬Śhad already crested the ridge above me and no longer offered even the remote companionability of blips on the bare hillside.

Our path, a crude mountainside incision with a grade of around 30 percent, made straight for the summit of this easternmost of Scotland’s Munros, the 284 revered, pesky mountains that occupy the lordly heights between 3,000 and 4,400 feet. It was self-evidently unrideable and, in my current state, barely walkable, cobbled with heaps of stones that gave way underfoot with every step. I lurched unevenly along, the cleats of my bike shoes clacking forlornly. If Samuel Beckett had placed his existentially distressed characters on bikes, I thought, they might look like this.

It was at this point that our leader, John Fulton, materialized beside me. He was clad in Scotland’s flag┬Śa blue-and-white cycling jersey blazed with Saint Andrew’s X-shaped cross┬Śhis bike raised above his shoulder like a trophy. Fulton bears a passing resemblance to his countryman Sean Connery and is the kind of outlandish physical specimen for which the region, whose traditional Highland games include log tossing and stone heaving, is renowned. A pioneer of off-road biking in Scotland, he quit his job as an engineer for Otis elevators nearly three decades ago to devote himself to being a guide. He remains, at 61, an extraordinarily powerful and sure rider. His small outfit, Wildcat ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°s, leads mountain-biking trips to far-flung destinations like Morocco and Mongolia, but the Scotland coast-to-coast is Fulton’s classic.

“We had a lad from New York City on the ride a few years back,” he said as I continued to struggle uphill. “It was a lovely day, like today, but as we were going up this very path, clouds started coming in. In no time, the skies were black. It started to rain. The wind was blowing brutally. By the time we got to where you and I are now, it was snowing.” He paused and turned to survey the valley below. “This was late spring, mind you. This lad from New York had been overheated one moment, and now he was freezing cold. The path was so slick he kept stumbling as he tried to climb.”

On cue, I slipped. Fulton chuckled, then went on with a grim matter-of-factness. “At one point the fellow looks at me with fear in his eyes and says, ‘John, I think I’m going to die up here.’ “

There was no punchline.

NOTE TO SELF: Next time the firm with which you book your vacation mandates that you load up on travel insurance┬Śand not just to cover lost luggage┬Śconsider that your notion of leisure is apt to be seriously compromised. My policy paid up to $1 million for “emergency medical evacuation and repatriation of remains.”

“That’s a lot of remains,” I’d told my wife, who was pregnant and staying home to mind our toddler. She didn’t want to talk about it.

It seemed a peculiar requirement. I wasn’t going off to claw my way up ice pillars, swim among sharks, or otherwise venture into habitats inhospitable to my species. I was going on a bike ride. It was something I’d done with great fervor since childhood, and I thought I was pretty good at it. Over the years, I’d ridden for transportation, for fun, for exercise, for adventure; aside from a few exciting spills and nasty abrasions, I’d never come home too much worse for the wear. I bought my first mountain bike in 1988, in the relative infancy of the craze. Back then, it seemed as though this garishly heavy, seemingly indestructible terror to hiking trails and sidewalks alike had sprung from the depths of a childhood fantasy. It could play rough. In fact, it performed with much greater ├ęlan through mud and gravel, over roots and vegetation, than on effete, smooth pavement. For me, it restored to biking a spirit of bravado. Above all, it granted access to the interiors of rugged landscapes previously the exclusive preserve of slow-moving backcountry tourists. Going for a bike ride reclaimed a measure of wildness.

But ten years ago, I moved from Montana to New York. My mountain bike languished in a corner of my apartment until I put it in storage and became the kind of person I’d previously scorned: a road biker. And I soon came to laud my road bike’s virtues┬Ślightness, speed, sleekness┬Śover those of my mountain bike.

It wasn’t until I overheard someone in a bike shop going on about how Scotland was fast becoming the new planetary epicenter of mountain biking┬Śdisplacing such vaunted but overcrowded sites as Moab and Crested Butte┬Śthat I felt my dormant inner trail hound stir. But I was leery of the hype. Scotland was hardly an undiscovered wilderness, its pleasures having long been enjoyed by such adventurers as golfers, whisky tourists, castle enthusiasts, and genealogy buffs. The landscape of the Highlands, deforested since antiquity for agriculture and grazing, was studded with nublike topographical formations I considered to be hills, not mountains. I embarked for the place expecting something like a pub crawl punctuated by a few leisurely turns through meadows.

Indeed, the trip sounded downright easy: an off-road scamper from inn to inn, with day routes covering 30 to 56 miles. (I knew I could cover 125 a day on my road bike.) A van would serve as luggage hauler/shuttle and, in case of sickness or injury or mechanical failure, as sag wagon/support vehicle. We began in Strontian, an end-of-the-earth setting in the far western Highlands, not far from the Isle of Mull. I arrived in the evening, the surrounding hillsides shrouded in fog and a cold drizzle falling. At a restaurant, I sized up our group as we mingled, pints in hand. The youngest was 34; the oldest, 67. You might have met this crowd on a cruise ship, I thought.

“It’s time to fatten you up for the kill,” Fulton told us as we gathered at a dinner table. Over lamb chops and mashed potatoes, we took turns introducing ourselves. I slowly began to suspect that I was surrounded by fanatics. Andr├ę, 38, from Brazil, had come to Scotland to regain his adventure-racing form after complex shoulder surgery a few weeks earlier. “Maybe I take it not so hard,” he murmured. Strider, 34, a dentist, had spent months training for Scotland at home, in the mountains of northern New Mexico, and had lately added some $1,200 in upgrades to his $3,200 dual-suspension bike, which he referred to as his “starter model.” Named for a character in The Lord of the Rings┬Śas were his two small children┬Śhe was so gung-ho, he seemed to have ingested a bike manual.

Barin, a 47-year-old American teaching in Venezuela, was a purist┬Śno GPS or fancy gear for him, just a devotion to legwork and risk┬Śand was joined on the trip by a German friend, Guenter, 67, who arrived from outside Cologne. The two men had crossed paths several years earlier, when Guenter was traveling across the U.S. in an RV and Barin was wandering around Nevada in search of UFOs. “I will not say ‘hate,’ ” announced Guenter, “but I extremely dislike pavement. I need an unpaved road. Nothing else will do. I have a hard time waiting until tomorrow morning to ride. I need a bike under my ass.”

Larry, who lived in the countryside outside Ottawa, was 59 but looked to be in his mid-forties. “For the past 20 years,” he said, “I was addicted to whitewater canoeing and kayaking. Now I’m addicted to mountain biking.” I asked him what he did for a living, and he identified himself, without irony, as an “addiction specialist.”

WE SET OUT the next morning in a dense, obscuring fog through which occasional glimpses of cliffs and scree broke. The trail was rutted and desolate. I rode past a man peering raptly into the murk through binoculars┬Śhad he lost his sheep?┬Śthen left behind any semblance of the company of civilians. Strider, apparently aptly named, bolted ahead of the group. “Don’t overcook your legs, lads!” Fulton called out. Just ahead of me, an enormous, shaggy cow crossed in front of Barin and then stopped, lowered its head, and showed off its prodigious horns. Barin listed sideways and toppled into a mash of mud and dung. “That’s a Highlands cow,” Fulton commented, maneuvering past. “It produces excellent meat.”

The path began climbing into the low clouds and, long after I imagined it should have leveled off, continued its ascent. We settled into a pace I considered less than leisurely. Fulton had promised an easy first day, but after half an hour I’d already had a stiff workout. Finally, after a short, steep stretch compelled me to rise from my saddle, the path leveled out. Drenched with sweat, I headed into a biting wind. Guenter appeared beside me. “You’re making a lot of noise breathing,” he pointed out.

A strong rain started to fall, and Guenter swore in German. When I paused to don a waterproof layer, he vanished into the clouds, and I found myself on a narrow asphalt path that made a shrill drop out of sight, winding around a series of hairpin turns. I had visions of myself skidding over the cliff’s edge and coming to rest a thousand feet below, in lime-green Loch Shiel. By the time I got to lake level, my hands and wrists ached from braking. The others were far ahead of me in the rain, rising and falling over the roller-coaster-like contours of a rocky trail hugging the shore.

It was now abundantly apparent that I had been mistaken about the specific nature of the ride. The others may have been hobbyists, but they rode with an intense abandon. After pedaling through the rain for five hours, we approached the town of Fort William, site of the 2007 UCI Mountain Bike & Trials World Championships. In the shadow of Ben Nevis, at 4,409 feet the UK’s highest peak, we found a pub and stopped for tea. Guenter refused to enter. “The old guys don’t like stopping,” Fulton whispered. “Afraid they’ll get stuck in place.”

We continued into the Leanachan Forest, west of Fort William, charging through thick, mossy woods on singletrack. It was an exhausting blend of cornering, accelerating up short rock berms, dropping into muddy hollows, pedaling around and over boulders, lurching over roots, and cascading across slick log bridges. We rode into the constant spray of each other’s wakes of dirt, water, and rock. “I’m beginning to like this rain,” Guenter remarked. My arms gelatinous, I wanted only to get to the finish line intact. When I reached our meeting point, a pub in the hamlet of Spean Bridge, it was still pouring.

I looked as if I’d been dragged from a bog. My lips were blue, and my back had been so jolted that it was painful to stand upright. While the others heartily drank beer, gabbing and laughing, I tore into an energy bar and huddled in a corner, dripping. Guenter, who had a GPS unit on his bike, came over and told me we’d ridden about 55 miles, climbing a total of 3,500 feet. I was eager to lie down.

After Fulton dropped me off at a nearby inn, the hostess stopped me at the threshold with an appalled expression.

“Oh, dear,” she said. “You can’t come in here like that.”

THAT NIGHT, I ventured out in a stupor after a shower and a rest. As I sat in yet another pub, the barkeep described the rotten weather to me as “the dreich,” explaining that when such conditions prevail, as they often do, “you can’t see the sides of the mountains, the clouds fill the valleys, and no matter how much you spent on your waterproofs, they do you no good.”

The dreich would persist for the next two days of riding, as we dipped and swerved and labored into the central Highlands. Yet despite the clammy cold and crummy visibility, despite the misery of my exertions, the sensation that mold was creeping over my skin, and a sentimental inclination toward the American Rockies, I was forced to come to terms with an encroaching realization: If a team of cycling fiends were to come up with a plan for an outrageous nationwide mountain-biking theme park, they could hardly improve on the Scottish Highlands.

The Highlands’ 15,000 square miles, about half the country, are home to only 400,000 people, a population density roughly equivalent to that of Idaho. As a mountain biker, you pretty much have the place to yourself, and the barrenness, the wildness, the hauntingly beautiful isolation of the moors and mountains are out of all proportion to the scale of the region. In this compacted landscape, worn to the bone by battering sea winds, the topography is constantly changing. The hills are short and steep, the climbs and descents swift, winding, and furious. You’ll go through dense woods, fight your way up to a rough, treacherous ridge, barrel down into a broad valley, then crash along a cattle path through a swampy meadow and find yourself looking down on an old stone village.

Being on a bike in the Highlands is a little like being on foot in Venice; you’re never quite prepared for what’s coming around the next corner, so you rarely have the opportunity to settle into a rhythm. Crossing an entire country this way, from one coast to the other, in a single week, while staying almost entirely off paved surfaces, is a real trip. As Fulton explained, the Scottish legal provision of “ancient right-of-way” makes all private land accessible to respectful recreational use┬Śexcept during hunting season. Although he’d led hundreds of rides across Scotland, he rarely repeated the same route twice and was always scouting new possibilities. We rode past farms, hunting lodges, and estates, on hiking trails and horse trails, and in national parks. Since the Highlands are sparsely settled and crisscrossed by a few millennia of footpaths and animal trails, we were usually forced onto paved surfaces only upon entering and leaving the villages we overnighted in.

By the third day, I was beginning to rediscover some comfort on the mountain bike. I allowed my body to relax into turns, laid back on the brakes, and began enjoying the sloppy, bone-jarring thrills of plummeting around blind turns and skipping over stumps. We climbed a few thousand feet to a wide, marshy plateau in the upper reaches of the Cairngorms, a mountainous region in the central Highlands, and found ourselves spinning along above tree line, Gulliveresque among stunted, windswept subalpine vegetation and glowing, kaleidoscopic heather.

Over the next few hours, Fulton upped the ante, guiding us through a water-saturated landscape. First we came to a few small streams that could, conceivably, be crossed via bicycle, provided that the rider pedaled feverishly and had the good fortune not to hit concealed rocks. Then we reached a broad creek whose banks had been washed out by springtime flooding. This one required a willing baptism. We clambered waist deep into the chill, rushing waters, bikes held overhead. (Guenter, who alluded to having nearly been washed away on a previous ride, was not pleased.) We emerged into a glen that looked innocuous enough, but the trail was pencil thin. “I pioneered this trail,” Fulton said, “if you can call it a trail.” He referred to it, coyly, as the Crocodile Run. It was only a moment before riders started plunging from sight. Beneath thick clumps of grass, the ground was studded with mud pits, quicksand-like formations that would swallow both wheels and topple the rider. Up ahead, Guenter went down again and again, issuing a stream of German vulgarities.

“Watch out for crocodiles!” Fulton called over his shoulder.

As the other riders staggered forward, I was left behind with Andr├ę, the Brazilian with the reconstructed shoulder. He was in agony and had dismounted his bike altogether. I followed suit. We dragged along, plunging through the ground every few steps. In this way we covered perhaps a mile in two hours. When we met up with the other riders, one suggested to Andr├ę that he might benefit from some Advil before bedtime.

“Advil?” he said. “No. Morphine.”

NO NATURE TALKS, no description of the geological fractures and collisions that had formed this pocked and pitted land intruded upon our relentless push across it. There was to be little emphasis on photo opportunities, no visits to castles or museums, no audiences with bagpipers or fiddlers, and few scholarly stabs at Scottish history┬Śaside from the occasional, obligatory “Bonnie Prince Charlie slept here.” Only once were the words “Loch Ness monster” spoken within earshot of me, and the subject was quickly blanketed in uncomfortable silence. Indeed, it became apparent early on that cultural appreciation was not to be our theme. The daily cycling was so absorbing, our eyes so focused on the few feet in front of us, we had little opportunity to converse with any Scots beyond Fulton and those who supplied us with food, drink, and shelter.

I began to suspect that in our determined pursuit of a good ride, most of us were largely oblivious to the fact that we were actually in Scotland. It had become a nameless country of obstacle-riddled single- and doubletrack and hard-won descents. At night, we gladly sampled the beer and the single-malt whisky and, like conscientiously healthful people, complained about the blandness and heaviness of the food. A shared interest in biking is a thin bond between adults, and to the extent we came to know each other, it was mostly through this lens.

Larry the Canadian, relatively new to the sport┬Śhe went over the bars on day two┬Ślacked finesse but was dogged and as strong as someone half his age. Barin, the old-schooler from Venezuela, had a near-philosophical aversion to riding in low gears. Luckily, he had the thighs of a fullback, though I believe I caught him on the smallest chainring once or twice. Barin’s devotion to mountain biking approached poignancy. One night, he spoke of the freedom that he’d always, and only, felt on a bike. He said that, as a teenager, he’d ridden all the way from Mexico to Canada on a road bike and, in his twenties, had coped with the death of his father by taking a long ride alone through Texas’s Big Bend National Park in the heart of winter. He said he didn’t even bring a tent, just rode through the snow for a week.

Guenter was eccentric to the bone, monitoring his vital signs as obsessively as his emotional state. “Today my knee feels very good,” he announced one morning, “but my anger is the same.” He told of how, in a previous incarnation, he’d built himself a boat and sailed halfway around the world, stopping in the Caribbean to, as he put it, “produce a baby in a lagoon.” He was a vociferous spokesman for the spiritual advantages of mountain biking. According to Guenter, it was primarily about escaping the known world. “There’s no adventure on paved road,” he told me. “You always know where you are. You never get lost. I’ve spent so many hours carrying my bike through woods, where no path exists. This is how you know you’re alive.”

On the fourth day, the sun came out. The deep, dark greens of the landscape grew paler and less foreboding, the streams seemed gentler, and everything had the glow of a 19th-century pastoral. I got sunburned. We reached our destination, an old stone hunting lodge, in the early afternoon, and lounged in our bike shorts, drinking and idling. The sun stayed out for the rest of the ride, but the relaxation expired. By the end of the fifth day, I’d made it up and over Mount Keen in my depleted state, suffering every lingering mile into the stodgy village of Edzell, our last overnight spot.

The next morning, as we approached the town of Montrose, the asphalt overtook the trails and we rolled toward the sea, knobby tires singing on smooth pavement, the landscape growing flat and broad. You could see the horizon. Entering the industrial outskirts of town, we rode past factories, body shops, car dealerships, were stopped at traffic lights and caught in the exhaust of delivery trucks and buses. Soon we steered onto an esplanade above a beach, pedaling past a miniature golf course and a snack bar. Workers sat eating lunch in parked cars, looking out at the North Sea. The water was gray and listless and stretched before us its vast, uninflected palate.