The Monk’s Tale

What possesses an American cleric, a man of history and scholarship, to renounce his vows, move to a crumbling stone farmhouse in a small French village, and spend his days digging potatoes and translating Thucydides? Bill Donahue goes in search of his favorite unconventional uncle.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

Tour de France broadcasts are almost cruel in their teasing. First there are the helicopter shots of the lovely French countryside: the green hills, the little stone churches, the sloping pastures filled with sleepy-eyed cows. Then we see the peloton snaking through some tiny upland village, past the boulangerie, the charcuterie. Then, just to drive the knife home, the camera’s focus narrows onto some completely charming outdoor café as the sun spills onto the cobblestones. In that instant, we’re almost programmed to think about alighting in a small village for a month, existing on fromage and Beaujolais.

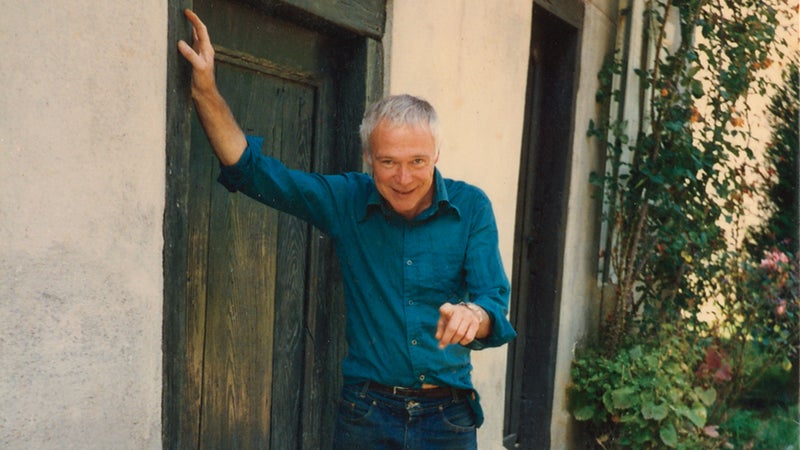

Ultimately, most of us will shake off the fantasy. But it really is possible to vanish into the French countryside. I know this because in 1980, my uncle bought a crumbling, centuries-old house at the northern edge of the Pyrenees, an hour from the Spanish border, and never returned to American life. William Joseph Donahue was a Catholic cleric—both a monk and a priest—as well as a sensitive poet who in middle age came to regard his Benedictine order in Washington, D.C., as hidebound and archaic. After writing a pained 28-page letter to the pope, beseeching His Holiness for “release from my religious vows,” and following a brief stint as a newspaperman in Canada, my uncle moved to Montastruc-de-Salies, a small village where the church bells toll hourly and sleekly clad cycling squads spin through in springtime, mixing with tractors and stray dogs wandering the road. The Tour passed through Montastruc in 2008, and this year, on July 24, Stage 16 will wend 1,300 feet up and down the Col de Portet-d’Aspet, about 15 miles from the village.

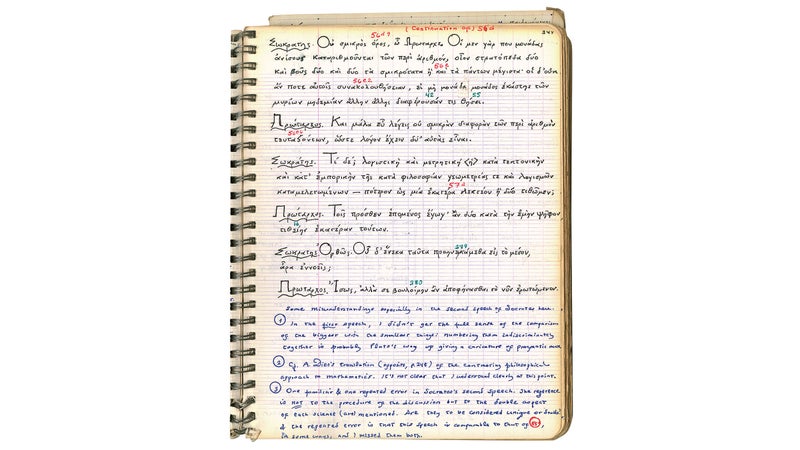

In Montastruc, my uncle settled into a different sort of monkish life, staying so close to home that he once managed to keep a fire burning in the hearth for 77 days straight. Sustained by a meager pension, he spent his mornings engrossed in a singular project: translating Thucydides’s eight-volume from Greek into Latin. He bent over each page with a magnifying glass and scribed his work into small perfect-bound notebooks, his handwriting so minuscule and precise that, looking at it today, I find it luminous, like the calligraphy on a medieval scroll. On afternoons he tended a meticulous vegetable garden in the shadow of a cragged peak, Paloumère, elevation 5,280 feet, from whose summit the entire Pyrenees is visible, stretching snowily from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic.

It’s difficult to convey how dear and formative, and also perplexing, it is to have such an uncle. He was a man of letters, and as a brooding and outré teenager inclined toward Hermann Hesse and Albert Camus, I idolized him. Uncle Bill had escaped the excesses of American materialism—a coup, in my eyes—and there was something beautiful and delicate about him. He stood apart. I knew this, I think, even when I was three years old and he showed up at my family’s house in Connecticut on a hot summer day, mischievously smirking and light on his feet when he grabbed the hose and doused me with cold water as I ran all over the yard, squealing with glee. He was a slight man—five foot seven and 140 pounds—and all his life he retained the buoyant, playful spirit of a small boy. I loved him; that never wavered.

Still, ensconced by his smoky fireplace in the Pyrenees, my uncle was so far away from the suburbs of Hartford, where my father, his only sibling, was an estate lawyer and where I myself, despite my anti-capitalist leanings, was a high school ski racer, an expensively equipped habitué of Mount Southington. Later I was busy with college. I got married, then began raising a daughter. I’m ashamed to admit that during the 26 years Uncle Bill was in France, I visited him only three times. We corresponded often, but there was a formality to my uncle’s letters, which might linger on the German theologian Hans Küng before signing off “Your Kinsman.”

At Saint Anselm’s Abbey School in Washington, D.C., he’d been a beloved teacher of history and Latin. He was a brilliant and socially nimble man, but at age 53 he took to his hermitage, embracing the Voltaire quote that would ultimately be engraved on his tombstone: “We must cultivate our own garden.”

Is it OK to cut away from the life of work, as my uncle did, and from everyday interaction with other people? In the dozen years since his death, I’ve wondered. I’ve also missed him. During this time I’ve become a diehard road cyclist, a whittled Strava striver with the standard fetish for vintage Gitane frames and cols de whatever. France exerted a certain tug on me. So this spring, a few months after my own 53rd birthday, I flew to Toulouse, rented a car, and began climbing into the hills.

I reach Montastruc on a cool Thursday evening, just as the village church bells are striking six, bracing myself for a sad story. Montastruc was an agricultural village when my uncle moved there, but family farming has suffered in France, and now, a French tourism official wrote me about the place in an e-mail, “Most of the inhabitants are old, quite old.”

When I step into the town hall, I’m surprised to find that the mayor, 57-year-old Bertrand Lacarrère, is slim and dapper and readying for a backcountry ski trip in Spain. Lacarrère, who also plays guitar in a rock band, is a socialist and a Paris native whose family roots in Montastruc date back to the 17th-century reign of Louis XIV. As a child, he spent summers roaming the countryside here—“like Tom Sawyer,” he tells me. “I caught trout in the river with my hands. I went hunting. I climbed into caves with other kids and met up with girls. I always knew that I wanted to do something for this village.”

The issues confronting the Lacarrère administration are small-timey (on billboards all over town, I’ll see public notices announcing the purchase of a municipal photocopier), but the mayor harbors a larger vision: to keep the village “vital.” He’s succeeded. The population is currently about 300 and growing. The Football Club Montastruc-de-Salies is 30 members strong, made up largely of twentysomething lads who work in Toulouse and return on weekends to occupy ancestral homes and enjoy the region’s burgeoning outdoor scene. These days the skies above Montastruc are often filled with paragliders dropping down from the spires of the Pyrenees. Nearby is the low-key ski resort Le Mourtis, with 1,600 feet of vertical drop. And in summers, open-air concerts are held in the ruins of a 12th-century monastery, Bonnefont, a half-hour away.

Uncle Bill was a slight man—five foot seven and 140 pounds—and all his life he retained the buoyant, playful spirit of a small boy. I loved him; that never wavered.

When I meander back out onto the street from the town hall at dusk, I make my way toward the cemetery at the base of the church tower. Because I can’t remember exactly where my uncle is buried, I stroll the gravel pathways, marveling at the flowers on the graves and the distinctly French plaques that crowd the long, flat top of each tombstone, memorializing the departed—a grandfather, a husband, a great-uncle.

There are, it seems, only three last names in this cemetery: Esquerré, Lassale, and Mailheau. My uncle is an outsider, and I hate to think of him lying here all alone, for I remember how much joy he brought me. When I was ten or eleven, Uncle Bill and I often played Ping-Pong in my family’s basement. Our battles were cutthroat. Once, after smacking a forehand that went wide, he slammed his sandpaper paddle on the table and cursed, “Damn!”

“I’m sorry, Bill,” he added quickly, remembering that he was a priest. “I’m sorry. I shouldn’t have said that.”

When I reach his grave, I find six memorial plaques. One I’d left there myself; another is from friends of my family. The remaining four are a happy mystery that I won’t solve tonight. I’m jet-lagged and ready for sleep.

My uncle's house is in a quartier of Montastruc known as Escat, a hilltop mini ham-let that consists of four dwellings and the ruins of a 700-year-old castle. The house is tidy and well maintained these days, occupied by a 13th-generation Montastruc native—a schoolteacher—and her husband, a football player.

When my uncle first arrived, he was the quartier’s only occupant, and the plaster skin on the walls of his house was so ravaged that blunt stones poked through. There was no insulation and no heat source, save for the fireplace—never mind that he was situated 1,500 feet above sea level and subject to the odd soggy snowfall.

What I remember most from my visits is the dim, amber quality of the light inside the house, and the cool, cave-like air, and how, when you stepped to the windows in the morning and threw open the wooden shutters, life poured in. There was sunlight suddenly, and songbirds darting about in the bushes; the peaks of Paloumère shone snowy white in the distance.

My uncle loved being here, in touch with an ancient, elemental world. In his letter to the pope, he said that he’d conceived “a romantic love for medieval history and Gothic art” as a teen, and in his poetry, which was never widely published, he described “the phoebes calling / through the reedlands of April / the almond-colored castles up irretraceable pathways.”

It was serendipity that he ended up on this particular hilltop. In 1975, when he was working on the editorial page of the Ottawa Journal, he met some young travelers, recent university grads from the Pyrenees. The Journal was ceasing publication, and my uncle’s new acquaintances offhandedly suggested he begin life afresh in France. A few weeks later he called one of them—a health care administrator named Nicole Bégué—from the train station in Toulouse, intent on looking for real estate.

In a village with almost no other foreigners, my uncle was known as l’Américain. In 1996, when he acquired his first neighbors, Christian and Nicole Bosc, they became “the people who live next to l’Américain.” He was well mannered and generous, freely sharing the fruits of his garden and loaning out his car, but he was so discreet that the Boscs didn’t even know he was Catholic. Intrigue built up around him. When my uncle gave the village officials a simple gift—a sundial he found in his house—it was regarded as possibly valuable, perhaps a remnant from the old castle. When I visit the mayor’s office, in fact, the sundial is still there, locked in a closet, a gray slab with a long, thin, rusty rod for a dial. Mayor Lacarrère tells me, “I’d like to put it out, but I’m afraid it would be stolen.”

To me the prospect seems unlikely. The dial looks suspiciously like circa-1970 rebar.

Nothing of material value existed in my uncle’s immediate orbit. This became crystal clear in 2006, when he died, at age 78, of kidney failure. My father flew to France to make the funeral arrangements. He called me from Montastruc and said, “I think we’re just going to get rid of everything here.”

“All of Uncle Bill’s papers?” I asked, suddenly stricken, doing the math. “All of his notebooks?”

“Look,” Dad said. “You are never going to read any of that stuff. No one else is, either.”

My father had some reason to regard his younger brother’s withdrawal to France as frivolous. His own life had been infinitely practical. For 50 years, he had worked at the same law firm, stowing in his closet five business suits—a Monday suit, a Tuesday suit, and so on. He put three kids through college, and he represented his brother legally, working with the Benedictines to leverage his small pension. But Dad also saw something pure in his brother, and when I protested that Uncle Bill’s papers had to be saved, it was he who paid for my transatlantic plane ticket.

I ended up cleaning out the whole house, which was not difficult. My uncle’s array of possessions had been pared down to the contours of his simple life, so much so that each object seemed to shine—this wooden spoon, this black-and-white television, this battered radio with a cord gnawed by mice. I couldn’t bring myself to take these items to the local version of Goodwill, and trying to sell them seemed absurd, so I summoned his neighbors to the house and, two by two, they arrived, offering condolences before solemnly trundling the relics home.

I gave the Boscs an aluminum stepladder, and Nicole told me that when my uncle was growing frail, she looked out for him. “The first thing I’d do in the morning,” she said, “was peer out my window to see if there was smoke coming out of his chimney.”

The bond was rooted in mutual respect. My uncle had grown up in the suburbs of Philadelphia, back when the area was still agricultural, and as a kid he’d earned a dime an hour helping a local farmer with his haying. He kept a victory garden during World War II. Country life was virtuous in his eyes, physical labor honest and good, and in Montastruc he was enchanted to be around people attuned to the land. Once, he told me, he went to a small party where a local family was unveiling its farm’s most recent vintage of homegrown wine. A man stood up and pronounced, “I can taste the rocks on the back of the hill.”

My uncle brought to gardening the same zeal for perfection that imbued his study of Latin and Greek. He was intent on cultivating one very specific sliver of land—maybe 50 feet by 40 feet—on the southeast-facing slope of a hill adjoining a cow pasture at latitude 43 degrees north, as expertly as he possibly could, and his gardening journals reveal an agronomist at work. Writing in French, he recorded the variety of each seed he planted, the date and the weather, and his stratagems for dodging the torrents of nature. “As a result of last night’s storm,” he wrote on August 15, 2001, “the corn fell. I tried to straighten it with string.”

A vague sense of defeat pervades every passage. “The potatoes are good,” he writes, “but they’re small.”

I suspect that he wished his connection to the French soil was not intellectual but rather ancestral, in his blood and bones. His closest friends in Montastruc—André and Jeannette Touzet, first cousins roughly my uncle’s age—lived together in the same rambling stone farmhouse where their fathers were born. My uncle spoke of the Touzets with a certain awe, as though they were made of a rare element yet to be discovered by science. “When daylight savings comes,” he told me once, “they never even touch their clocks. They live by the hours of the sun, and at home they don’t speak French. They speak Languedoc,” a regional Latinate patois.

My uncle met the Touzets during his first Montastruc winter. When his pipes froze one night, he walked a quarter-mile downhill to their home bearing a few plastic jugs and, in gentlemanly tones, asked if he could fill up at their spigot. Soon he was visiting once a week to chat about the weather, or the eggplant in his garden, or the mushrooms he found while foraging in the woods.

André Touzet died in 2006, but Jeannette is still flourishing. When I knock on her door and announce that my name is William Donahue, I am instantly accorded VIP status. She is 90 now, and though she is silver haired and stooped, her smile still glows; in her wholesome, earthy way, she leaves Catherine Deneuve in the dust. I’m smitten, too, but thanks to my bad French and her challenged hearing, all we can really do is grin at one another as we sit at the long wooden table by her brick hearth, which has been seared black by decades of fire.

When I return with an interpreter, Madame Touzet is able to tell a story that pierces me. We’re talking about the Touzets’ dogs. “They were all hunting dogs,” she says, “and Monsieur William never hunted. He had no interest in killing things, not even a snake that got into his garden. He was interested in the dogs, though, and he always wanted to be included, so he went on a couple of hunts, just to watch. He became friends with the dogs. Sometimes he fed them scraps.”

She shows me a picture of my uncle, 55ish and lean, wearing a white T-shirt and high mud boots as three dogs circle tightly around him. He’s bending low to pet one, and his face glows with delight. “See this one here?” she says. “When she wanted sympathy, she would always go up the hill to Monsieur William’s garden. When she was very sick, she wanted to be with him, so I called him. He came down and laid her in his car. She died right there, in the passenger seat, on the way back to his house.”

“How did you know that the dog wanted to be with him?” I ask.

“I just knew,” says Madame Touzet.

It was only after my uncle died that I realized how much suffering his sensitivity caused him. His 1975 letter to the pope is a long confession exploring the anguish he suffered as a youth, as he set one woman after another up on a pedestal, only to be crushingly rejected. “At 16,” he writes, “I already cast myself in the role of the poet reaching out for unattainable beauty in romantic love.”

When he was 23, he told the pontiff, his devastation over one young woman was so total that he decided “I would probably never be able to love anyone else.” He gravitated toward the Church and became a novice monk at 25. The rites of Catholicism—the incense, the gleaming Communion chalice—held a shimmering allure for him. He romanticized these things in the same way he did women, and he hoped, he wrote in his papal letter, that his carnal longings “would all be positively subsumed by my growing interest in the understanding of the Gospel and theology.”

They weren’t. The whole time my uncle wore the cloth, women kept falling for his gentleness and wisdom. He was the sage to whom they wrote long, soul-searching letters. The relationships were platonic but steeped in shared secrets and a tenderness that set my uncle in a tizzy. In the early seventies, when he met a nun poised to leave her religious order, he was as innocent and vulnerable as a middle schooler. A true romance blossomed. Then it disintegrated, and my uncle fell into, he writes, “a state of utter desolation and confusion.”

His fragility was not simply emotional. It was neurological as well. He had epilepsy, but he didn’t learn this until after the nun left him and he sat down to draft a poem. Concentrating, he suffered a grand mal seizure that left him unconscious for 45 minutes. “I hoped that I would die,” he wrote the pope, “or that I would be a permanent invalid for whom any future would be impossible.”

Soon after he arrived in France, his friend Nicole Bégué—one of the travelers he’d met in Ottawa—married a doctor, Henri Llop, who was so taken by my uncle’s quiet charm that he insisted my uncle live close by, in case the epilepsy flared. Over the ensuing 26 years, he dined with the Llops once a week. By candlelight in my uncle’s dimly lit kitchen, or beneath the chandeliers in their elegantly appointed home, they ruminated and laughed over delicately prepared foie gras and goblets of Bordeaux. “No one could listen like he could,” remembers Nicole. “If someone died, if you were grieving, he would grieve with you.”

“You look just like him,” she told me when we met. “You even walk like him.”

Once, he told me, he went to a small party where a local family was unveiling its farm’s most recent vintage of homegrown wine. A man stood up and pronounced, “I can taste the rocks on the back of the hill.”

My uncle flourished in Montastruc, seizure-free. He’d left a religion that required the suppression of natural urges to partake in keen sensual pleasures—the sun on his back as he hoed broccoli, the piquant taste of a tomato he’d grown himself, in cow shit given to him by the Touzets. He was happy.

Which is not to say that Uncle Bill let his hair down. He remained celibate. I don’t know why—it’s not something he would ever have spoken about to anyone. But my read is that, once he came out from under the weight of the Church’s strictures, his sense of personal deprivation began to dissipate and he gradually became OK with being a little different from others. Maybe he realized that what he had to offer the world was a certain stillness, a shining peacefulness.

His retreat from the mania of modern America was nearly total. When I visited him in 2003, he was unaware that there was a chain of coffee shops called Starbucks. All he could tell me about the Internet was that he’d read about it somewhere.

In the weeks since my return from Montastruc, I’ve been thinking a lot about what a single life can add up to. It is good, I’ve decided, to achieve things—to rack up 300-mile weeks on the bike or to build a stable career. But very few people are able to transcend the rat race with sustained elegance. I’ve tried to do it myself, moving from a big city to the sticks of New Hampshire, but I keep buying crap on Amazon Prime. My uncle actually left the fake, ephemeral world behind, and of late I’ve felt like showing his notebooks to everyone I meet and saying, “Look at this—in our own time, someone lived with an antique patience and care.” I often feel like his example could save us. It could slow us all down just a little.

But the story of his years in France is, at bottom, not cosmic. It is small; it is local. Just before leaving Montastruc, I visit Madame Touzet again, this time with Nicole Bosc, and we talk about the plaques left on my uncle’s grave. “Yes,” Madame Bosc says, “that was us. That was everyone in the village, everyone from every quartier. You wouldn’t allow a person like that to die without being honored. Your uncle created an interest—in the simplicity of his life, in his friendliness. That he came from so far away and took the time to learn about us and to care—that was important.”

Madame Touzet is sitting across from me, her hands clasped on the table, nodding in assent. When our eyes meet, she smiles: a flicker of incandescence. I feel myself swooning inside. Then she speaks.

“He was interested in the village and everyone in it,” she says. “The gardens, the cows, the dogs, the cats. He was a good person. He was esteemed.”

Bill Donahue ( @billdonahue13) wrote about biologist Bernd Heinrich in November 2017.