“I SEE TRIUMPHS IN WORK AND everlasting love…,” the fortune-teller predicts in Spanish, winking at the circling band of compadres eavesdropping on my optimistic future, which gets better and better with every Guatemalan bill I drop into his outstretched palm. Taking me for a gringa with endless coin, he demands another quetzal before dispensing more good juju, but I'm satisfied with the “everlasting love” part and move on.

It's a Sunday during Lent and I'm in San Andr├ęs, a dirt-crusted village west of Antigua, Guatemala, in the shrine of Maxim├│n, a fallen pagan saint who, in Maya-Catholic tradition, is said to be a badass combination of Judas Iscariot, the explorer Pedro de Alvarado, and various Maya deities. A line 50 worshippers long snakes its way through rivers of candle wax and smoke, offering gifts of alcohol and flowers to the wooden santo holding court in what appears to be a stationary Popemobile strung with Christmas lights.

I watch Maya women dressed in embroidered huipiles spark up boiled-egg and cigar altarsÔÇöeggs to ward off evil, cigars to satiate Maxim├│n's tobacco habitÔÇöwhile shamans fill their cheeks with aguardiente, then douse waiting pilgrims with the alcoholic spray. ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°, firecrackers explode with staccato bursts. This orgy of carnivalistic religiosity is wreaking havoc on my Lutheran sensibilities, but I have to admit it's the liveliest church service I've ever encountered. The firecrackers were an offering from John Fox, a 36-year-old archaeologist and one of my seven American traveling companions. He's hoping Maxim├│n will return the favor by blessing the eight blue candles we've left burning on the altarÔÇölocal insurance for safe travels.

But as we soon discover, Maxim├│n's good graces don't come easy. What began as a benign month of wandering through Mexico, Belize, and Guatemala would suddenly take a turn toward the disastrous. In the week to follow, we'd encounter an armed mob, lose a $4,000 Leica, shear off a trailer tire while inching up a gnarly pass in the Cuchumatanes mountains, and watch Nate Strandberg, a 25-year-old graphic designer from Minneapolis, heave his tamales out the car window while the rest of us decided how best to jury-rig the broken tire.

Such mishaps are to be expected along La Ruta Maya, a loosely defined route through Central America's Maya heartland, a place that stirred poet Wallace Stevens to enthuse about the “wild country of the soul,” and where grace and beauty duke it out with evil and misfortune at every turn. In the jungly lowlands, deadly fer-de-lance vipers slither atop centuries-old ruins. In the highlands, 21st-century Maya, many of them refugees of the 36-year civil war that left 200,000 Guatemalans dead or disappeared, eke out sustenance from agricultural plots that grow less corn with each passing year. Throughout this history-scarred country are mountain-bikeable dirt roads, paths packed down by generations of barefoot villagers, mysterious unexplored cave systems, swaths of palm-lined beaches, and jungles thick enough to swallow you.

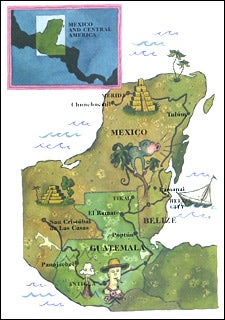

Our 4,331-mile, six-week circle tour started in the parking lot of a sanitized Austin, Texas, Super 8 motel, where we hopped into a Suburban, inserted Blood on the Tracks, and let the world unroll beneath the steel-belted radials. Herewith, a few vignettes, should you decide to devise a Ruta Maya of your own.

YUCATÁN, MEXIO

Five days and 1,786 miles south of Austin, I find myself digesting lunch in a hammock suspended above a turquoise pool. Our destination was a campsite near Chunchucmil, a Maya ruin about 50 miles southwest of M├ęrida, where we planned to meet up with archaeologists mapping the unexcavated site. But we were temporarily sidetracked by the lure of lunch and a siesta at Hacienda Santa Rosa, a 19th-century sisal plantation turned swank hotel.

Washed in blinding shades of lavender, yellow, and scarlet, Hacienda Santa Rosa glitters like a desert mirage in The-Middle-of-Nowhere, Yucat├ín. It isn't a stretch of the imagination to picture Gabriel Garc├şa M├írquez dreaming up One Hundred Years of Solitude from a rocking chair on the veranda outside his own Maya-themed casita, which comes complete with its own reflecting pool.

Lunch was fresh guacamole, homemade tortillas, and lemonade in the ballroom-size dining room. We feasted while a more well-mannered Museum of Natural History tour group (here, no doubt, to tour Jaina and the half-dozen other major Maya ruins nearby) wandered the grounds, gaping at strolling peacocks and gardens of scarlet bougainvillaea. After lunch I made a beeline for the hammock and let the sun bake my Nordic skin to a cancerous shade of scarlet, but I was too comatose to notice. The previous night I had whiled away the hours gazing at the stars from under my mummy bag atop a 20-foot limestone mound at Oxkintoc, a 2,000-year-old Maya ruin just outside the village of Maxcan├║.

Taking advantage of the staff's preoccupation with the Museum of Natural History visitors, the eight of us snuck a dip in the pool, then wavered for a few minutes, debating whether we should spring for a casita. “Nah,” we decided, and shoved off before our dripping bodies betrayed our bad manners.

LAMANAI OUTPOST LODGE, ORANGE WALK, BELIZE

Two days later, after an overnight stop in Tul├║m for yet another swim, this time in the Caribbean, we arrived at Lamanai Outpost Lodge, a resort compound on the shores of the New River Lagoon, 100 road miles northwest of Belize City. A haven for animal lovers and bird watchers, LamanaiÔÇöMayan for “submerged crocodile”ÔÇöis the kind of place where you feel like wearing khaki, with its thatch-roofed bungalows, creamy coconut drinks, and giant meat hooks sprouting banana bunches.

“When are we going to hear a howl?” I whined to Brenda Salgado, the director of the resort's Field Research Center, who was taking me on a jungle hike to the Lamanai ruins, a cluster of 2,200-year-old crumbling temples, the site of one of the longest continuously inhabited Maya cities in all of Central America.

“Monkeys aren't on a time schedule, you know,” Brenda sighed.

The two of us had been up to our necks in palm fronds for the last hour, straining our ears for the jet-engine call of a black howler monkey, which, on a good day, can be heard up to a mile away. But Salgado's guttural burping noises didn't even raise Micklet, the semitame howler that researchers are vainly trying to repatriate to the wild. But these primates prefer the 5 a.m. howling shift, and I had been a late arrival, having decided to boat 35 miles from the town of Orange Walk down the New River. It had been an excellent choice. The waterway teems with jaguarsÔÇöall of which must have heard us comingÔÇöMorelet's crocodiles, kinkajous, howler monkeys, and at least 384 bird species. The kicker was sighting a family of four jabiru storks nesting 100 feet up a towering ceiba tree. The largest bird in the Americas, the jabiru stork has an eight-foot wingspan that is intimidating even through binoculars.

Sweaty, Brenda and I headed back for a beer at the lodge's open-air bar. I took mine down to the dock to watch the sun set over the river. Lost in thought, I was oblivious to what sounded like a speedboat sputtering to a start. The sputtering soon turned to a full-throttled roar. Sure enough, 20 feet above me, hanging from all fours in a guanacaste tree, Micklet was making a holy racket, causing the khaki-clad visitors to flock from every direction. I sank back into my deck chair, nursed my beer, and basked in the cacophony.

EL REMATE, LAGO PETÉN ITZÁ, GUATEMALA

After an uneventful border crossing into Guatemala we found El Gringo Perdido, a cluster of classy, yet primitive, palapa huts a few miles outside the town of El Remate on Lago Pet├ęn Itz├í, a vast body of water surrounded by hills and palm trees. Lacking electricity and other guests, El Gringo Perdido felt bewitchedÔÇöespecially at night when the caretaker lit the oil lamps and tiki torches. After a day's stay, we decided that El Gringo Perdido is the ultimate base camp from which to laze in the sun, swim, rent bikes and kayaks, and explore nearby Tikal, so we settled in.

The next day we drove to Tikal, 30 minutes north of the lodge and the Manhattan of the ancient Maya world. The 222-square-mile park was once home to nearly 100,000 people, boasting the highest population of artists, architects, jewelers, astronomers, and warriors, along with the infrastructure to keep them all happy: ball courts, sweat baths, and brilliantly painted royal palaces. No one knows why the 2,700-year-old site was abandoned in a.d. 900, which adds to its mist-shrouded allure.

On our first trip up the dozens of precipitous steps of Tikal's Temple of the Masks in the Great Plaza, we were clipped by a birder hauling a telescope large and powerful enough to see life on Mars. He huffed past us stammering, “I…I…I…just saw an orange-breasted falcon!”

We were witnessing a moment of birding nirvana. The orange-breasted falcon is one of the world's most rare and reclusive birds of preyÔÇöreportedly there are only 19 in all of Guatemala and Belize. At the top of the temple, the man offered us a gaze through his telescope. Sure enough, sitting in the crux of a ceiba tree was a smallish, orange-breasted bird with a menacing beak that looked like it could fillet small feathered creatures. Impressive, to be sure, but I failed to muster the passion radiating from our new friend and was far more impressed with the eerie hollow sounds that radiated from the bowels of the temple as we stomped back down the stairs.

Back in El Remate, we ate dinner at Casa de Don Juan, a two-story restaurant on the shores of Pet├ęn Itz├í. Our host, Juan Chamorro, prepared us a special delicacy.

“They call it 'The Royal Rat,'” he told us, producing a platter of tepesquintle, an oversize rodent with a massive butt. Surprisingly, the varmint tasted quite similar to my grandma's pot roast. I savored every bite until Juan let it slip that the beast is nearly endangered. Poachers, he added, get fined hundreds of dollars if caught trafficking in tepesquintle. I choked down my last few bites, which suddenly began to taste like rat.

FINCA IXOBEL, POPTÚN, GUATEMALA

The next leg of our journey, to Lago Atitlán, west of Antigua, was a few hundred miles. We flew past pink evangelical churches, a mom sitting on a tree stump nursing her baby, a man combing his hair in a rearview mirror, and a young couple at a bus stop absorbed in a marathon smooch.

At dusk, we arrived at Hotel Ecol├│gico Finca Ixobel, a conglomeration of guest houses, campsites, and Crusoe-esque tree houses built around massive pines at the foot of the Maya Mountains. The inn offers its global backpacker clientele horseback riding, tubing, jungle exploration, caving, and ping-pong, but the main attraction is the nightly candlelit dinner served family-style at communal picnic tables.

That night's dinner was overcrowded, so we sat around the ping-pong table swapping jokes with a young couple from Denmark. A dark cloud descended over the vegetarian eggplant and lentil dishes, however, when the couple informed us that, back in 1990, the inn's American owner, Michael De Vine, was found beheaded by the side of the road just a mile away. Five years later, it was reported that the murder was ordered by a Guatemalan colonel on the CIA's payroll. To this day, nobody knows what really happened. Determined not to let this all-too-common act of terrorism scare her out of her adopted country, De Vine's wife Carol still owns and operates Finca Ixobel.

Dinner soured. So we turned to drinking. Every time we emptied a beer, we hatched a mark next to our name on the guest list in the kitchen and headed to the communal fridge for more. By the end of the night, the hatch marks were a messy blob and our table was transformed into a rollicking multicultural ping-pong tournament, played more off the walls than on the table.

LAGO ATITLÁN, GUATEMALA

A day later we rolled into Panajachel, the largest, most resorty city on the shores of Lago Atitlán. I was mesmerized by the conical volcanoes ringing the water, and deflated by the rows and rows and rows of identical souvenir stands lining the streets. Internet cafes bustle with blond Americans, and street signs belt out advertisements for immersion Spanish classes. Panajachel is obviously a featured attraction on the Gringo Trail. Being gringos, we found Müller Guest House, a German bed and breakfast in the center of town with three rooms, hot showers, a lush courtyard, and Latin MTV.

I was curious to experience the region's much-touted Maya authenticity, so I hired Rodrigo Gonzales Garc├şa, a 20-year-old Maya boat driver, to take me to the village of San Lucas Toliman across the lake. The rest of the group decided to hike a precipitous roller-coaster trail winding through mountainside agricultural milpas, or plots, which have metamorphosed the steep terrain into one gigantic patchwork quilt of greenery.

Rodrigo and I landed at the dilapidated village's public docks and stepped into the 19th century. A Maya woman who looked to be 100 years old was carrying a load of firewood suspended from a tumpline around her forehead, while her husband carried the bloody carcass of an entire cow.

We walked around the village, buying passion fruit, ice-cream sandwiches, and beaded jewelry from five-year-old girls. In appreciation for Rodrigo's services, I bought him lunch at the only tourist hotel in town, Pak'ok, a surprisingly lavish yellow-stuccoed hacienda that caters to wealthy clientele from Antigua. We sipped Cokes on the patio amid immaculately sculpted gardens and quietly watched the distant lake shimmer in the sunshine. I quizzed Rodrigo about his life in Panajachel and asked him how much he made ferrying tourists across Lago Atitlán.

“Three hundred quetzales a week,” he replied proudly, about US$38. I got the bill for lunch: It was frighteningly close to 300 quetzales. I'd just spent almost the entire weekly salary of my guide on one lousy meal, an instant reminder that life is, simply, whacked.

SAN CRISTÓBAL DE LAS CASAS, MEXICO

Our final destination is San Crist├│bal de las Casas, in the southern state of Chiapas, Mexico, soul sister to Santa Fe, New Mexico; Berkeley, California; and Antigua, Guatemala. To get here, we'd wound up, down, and around the Cuchumatanes mountains, stopping to hike into roadless villages and sleep on the dirt floors of Maya families who have barely seen white folk, let alone shared their homes with them.

We finally arrived in the border town of La Mesilla, and after two hours of inhaling fresh tar fumes and drinking icy Coca-Cola, we were finally granted passage back to Mexico. By early afternoon we pulled into Hotel Posada el Cerrillo, a salmon- and periwinkle-colored hotel in downtown San Crist├│bal with whimsical patios heading off in every direction. A spiral staircase wound its way up to a room with a 360-degree view of the city's red-tile roofs. The breezy aerie is an ideal spot for travelers desperately in search of an afternoon siesta. So we napped.

In the late afternoon, I made the rounds of the city and hit the mother lode of markets at Santo Domingo church, where I bought amber earrings, knitted footbags, and all the Chiclets I could stomach. I sat on the top of a wall in the middle of the market and took out my copy of Pablo Neruda's memoirs, hoping somehow that this Latin setting would inspire my own poetics. I read a few lines, jotted down a few of my own, crossed them out, gave up, and started walking back toward the hotel.

That night, our last before we began the 2,000-mile slog home, we shifted into club mode, stepping out to the Blue Bar, San Crist├│bal's happening downtown dance spot where a local band mixed it up with Santana covers and Latin chart toppers. A gym instructor named Gustavo asked me to dance, and I sillily started to salsa. We merengued, salsa'd, and boogied into the wee hours. And then it suddenly hit me: The fortune teller in San Andr┼Żs really did predict my future. I wasn├Ľt head over heels for Gustavo, but I had definitely fallen in love with this place that so inspires the wild country of the soul.

Road-tripping on La Ruta Maya requires a trustworthy vehicle. But unless it's your own, chances are this tour will remain a pipe dreamÔÇöintercountry Latin American car rentals are as tangled as the region's politics. But if you can afford to throw a few extra miles on your Outback, or have the patience to navigate the rental web, here's where to catch a siesta and find a car in Mayaland:

Hacienda Santa Rosa, Yucatán, Mexico

Phone: 011-52-99-44-3637

Web: www.grupoplan.com

E-mail: reservations@ghmmexico.com

Rates: Doubles, $285Ð$483 per night

Lamanai Outpost Lodge, Orange Walk, Belize

Phone: 888-733-7864; 011-501-2-33578

Web:

E-mail: reefsruins@aol.com

Rates: Doubles, $99Ð$125 per night

El Gringo Perdido, El Remate, Guatemala

Web:

Rates: Camping, $3 per night; open hut, $6 per night; bungalow, $14 per night

Hotel Ecol├│gico Finca Ixobel, Popt├║n, Guatemala

Phone: 011-502-410-4307

Web:

E-mail: fincaixobel@conexion.com.gt

Rates: Tree-house doubles, $9 per night; private bungalow with hot shower, $24 per night

M├╝ller Guest House, Panajachel, Guatemala

Phone: 011-502-762-2442

Web:

E-mail: htmuller@amigo.net.gt

Rates: Doubles, $45 per night

Hotel Posada El Cerrillo, San Crist├│bal de las Casas, Mexico

Phone: 011-52-967-81283

Rates: Doubles, $20

Car Rental

Avis rents four-wheel-drive SUVs in Mexico, Belize, and Guatemala. The cost is approximately $594 a week including taxes. The hitch: Rent a car in Mexico or Belize and you can't leave the country with it. Rent a car in Guatemala and you can drive it in Belize (for an extra $20) but not in Mexico. Call 800-331-1084 or visit for details.