EVER SINCE I devoured the first of many 1950s jungle films—you know, those cheesy concoctions based on Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1912 novel, The Lost World—with explorers edging along precipitous ledges into the jaws of giant iguanas, I have harbored a secret hope that it wasn’t too late to climb the walls of my own formidable gorge, to search out the marvels of the forest beyond the clouds. And then one day I finally got to do it.

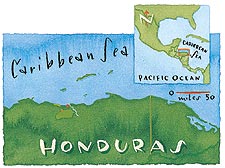

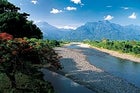

Peak experience: Pico Bonito National Park

Peak experience: Pico Bonito National Park

Admittedly, this lost world was pretty convenient. Instead of a weeklong trek with grumbling bearers who would throw down their loads at the first sign of a pterodactyl, a courtesy van met me at the La Ceiba airport in northern Honduras for the 20-minute jaunt to The Lodge at Pico Bonito, the area’s brand-new, and first, upscale eco-resort.

Located a few miles west of La Ceiba (the company headquarters of Standard Fruit de Honduras and a rough-and-tumble Caribbean party town), the lodge borders 429-square-mile Pico Bonito National Park, the second-largest in Honduras. In a generous 1987 decree, all land in the country above 6,000 feet was declared park territory, and around La Ceiba that meant the town’s precipitous backyard.

I had seen the park before, through the plexiglass porthole of a puddle jumper bound for the Bay Islands. Gaping at the cloudforested peaks, misting waterfalls, and tumbling rivers, I’d thought: “What a cool place! But how do I get there?”

The lodge answers that question quite comprehensively. Set at the base of a ridge that divides the watersheds of the Corinto and Coloradito Rivers, the structure (built, eco-wisely, from timber downed by 1998’s Hurricane Mitch), resembles a Wyoming millionaire’s summer home, with 8,036-foot Pico Bonito dominating the view like a tropical version of Grand Teton. You could spend an entire vacation by the pool, watching that cone-headed brute break up the weather, if there weren’t so much else to do. I spent five minutes in my room, admiring the craftsmanship of the rugs and furnishings, testing the mattress—superb!—before I was drawn back outside to watch the mountains fade into the night.

Since my camping gear had been erroneously routed to San Pedro Sula, I took advantage of the lodge’s myriad amenities—no sense in rushing off into the sticky wilds when luxury and a jungle primer awaited on the premises. On its excellent hiking trail, a three-hour loop into the park, hundreds of wooden steps ease you up a ridge between the two rivers, through old-growth forests filled with trees as thick as silos. Spur trails along the way lead to three-story observation towers (one with a view of a colony of brilliant black-and-yellow birds, called chestnut-headed oropendolas, squabbling over their stocking-shaped nests); elaborate wooden stairways spill down to waterfalls and pristine swimming holes ideal for sluicing off a light jungle sweat. The trail runs right up to the ramparts of Pico Bonito itself before circling back to within a stone’s throw of the pool and king-size bed of one’s well-appointed casita.

Set aside a couple of hours for the lodge’s butterfly farm, downslope in the orange grove. The farm includes a birthing shed, where you’ll see all stages of metamorphosis in action. Then you can watch the adults flap about, sucking nectar in the screened butterfly house. Next door is the serpentarium, with its collection of boas and vipers, and a resident herpetologist, James Adams, who leads night hikes on the trail, shining his headlamp to look for eyelash vipers in bird-of-paradise bracts. You might see kinkajous, bats, super-size insects, armies of leaf-cutter ants, and even an elusive jaguar—all without leaving the property.

But birders, wildlife lovers, paddlers, and fishermen take note: The really cool stuff lies beyond the lodge, in the untapped wilderness that has become a boon for the region’s burgeoning eco-adventure biz. I signed on for a half-day trip to Cuero y Salado Wildlife Reserve, where canoe trails weave through coastal mangrove forests accessible only by a 2.4-mile jaunt on a narrow-gauge railway car. Our guide, Jorge Salaverri, not only knew where to spot many of the 196 bird species found there, he could whistle many of their calls with perfect pitch.

About 40 minutes east of the lodge, on the far side of La Ceiba, the Cangrejal River carves thousand-foot-deep gorges through the park. Our group paddled two hours on Class III-IV rapids around gigantic granite boulders, and even in the bone-dry early-summer season, the river was frisky enough to unseat me twice from my inflatable kayak. Another good way to get wet is an excursion to the Cayos Cochinos, the least developed of the Bay Islands and close enough to La Ceiba for an overnight or weekend trip. While the reef around the Cayos Cochinos Marine Reserve has suffered from bleaching, it’s slowly making a comeback. But the best reason to visit the Cayos Cochinos is for their isolated ambience. The solitary lodge, the Plantation Beach Resort, has the only phone, and, better yet, the only bar.

I covered a lot of territory in one week, but seaside, barside, or hanging in my hammock, I was lured by Pico Bonito urging me to come on up and have my butt kicked.

So I called Kent Forté, an American expat who’d helped build the lodge and had offered to put together a bushwhacking team for a three-day trek into the backcountry. The team included Salaverri, who was not only an expert bird caller, but also handy with a GPS and a topo map; German Martinez, a young local guide from the lodge; and our head machetero, a campesino named Ramón. As we set out with loaded packs from the banks of the Cangrejal, Ramón warned us about El Sisimite, the Honduran version of Bigfoot. According to him, the hairy beast had been scaring off park intruders lately.

“Sí, para arriba,” Ramón said, cocking his thumb across the Cangrejal and up—straight up—to the top of a cliff where a 264-foot waterfall, El Bejuco, twisted and braided in the breeze from the coast.

What I wondered was how El Sisimite got up there.

It looked impossible but turned out to be the best sort of semi-life-threatening scramble, half hiking and half tree climbing. We stuck to the shaded understory, using saplings for ladder rungs and kicking steps into the soft duff as German and Ramón slashed open a seldom-used trail. At high noon we skidded down into the streambed at the mouth of the waterfall—a little Eden of cool repose. An iridescent blue Morpho cypris butterfly flitted about in the sun-dappled updraft where El Bejuco cannonaded into the abyss, misting us in the shady bower. Combined with my incipient exhaustion, dehydration, and vertigo, the seemingly endless view of the white-capped Caribbean, clear out to the Bay Islands, gave my goosebumps goosebumps.

At the top of the first ridge, a thousand feet above El Bejuco, the trail was a surreal hybrid of lichen, fern, and brush, springy as an old mattress. You could plunge a stick through it, or walk a stout limb out over a gut-sucking drop. Confident as German and Ramón were, they also knew we were following the trail they had been lost on during a previous scouting mission. Only a handful of people, Forté among them, have summited Pico Bonito.

An hour before dark the guides hung a tarp and started a fire to drive off the few mosquitoes, and we settled in for the night. Though we’d seen only feathered wildlife on the ascent, unseen things scuttled in the leaf litter beyond the campfire. Chattering michos de noche—night monkeys—crept close to us in the can-opy above. Every few seconds a click beetle with a pair of bioluminescent antennae, looking just like two little truck headlights, would streak out from the dark tree trunks. With a cool breeze blowing, the fire glowing, it was wonderfully peaceful up there, as luxurious in its own way as life back at the lodge. “El Sisimite, eh, Ramón?” I said. Ramón just winked.

La Ceiba, the jumping-off point for your Honduran adventure, may be a fun town for a pub crawl, with Salva Vida, a tasty local brew, and thumping punta music. But just say no to that next beer. Only a few miles beyond this spicy mestizo, Afro-Caribbean Garifuna, and expat community lies a lush jungle replete with frothy rivers, virgin rainforest, unclimbed peaks, and beachfront sports galore.

At The Lodge: Stay at The Lodge at Pico Bonito ($125-$190 per night; 888-428-0221; ), 20 minutes west of town, and you’re within earshot of the Corinto and Coloradito rivers, which offer Class V steepcreek challenges for expert paddlers. Thirty minutes east of La Ceiba, the Class III-IV Cangrejal tumbles through a 1,000-foot-tall gorge. For half-day rafting trips on the Cangrejal, contact Jorge Salaverri, proprietor of La Ceiba-based La Moskitia Ecoaventuras (504-442-0104; ).

Farther Afield: As his company name declares, Salaverri is the man to see about camping trips into the vast Mosquitia wilderness, a seven-hour drive east of La Ceiba, where he takes clients on a gentle 28-mile float on the Wampœ and Patuca Rivers. Salaverri also leads day hikes into Pico Bonito National Park (), home to jaguars, peccaries, monkeys, more than 250 bird species, and, of course, El Sisimite, the Honduran version of Bigfoot. Before hitting the backcountry, check out “Butterfly Bob” Lehman’s Butterfly and Insect Museum in the suburbs of La Ceiba. Bob is an enthusiastic teacher and his madly colorful collection of 10,000 insects from 38 countries is a knockout ($1 per adult, $.75 per child; 504-442-2874; ).

Birders, beast masters, and fly casters all should save a day for the Cuero y Salado Wildlife Refuge (504-443-0329; ), a 32,741-acre coastal reserve 20 miles west of La Ceiba. Judging from the countless big boils and flashes of silver I saw (and from watching a guy catch tarpon by the dozen on a hand line), this is an untapped fishing paradise—so untapped that there aren’t any sportfishing guides. But Jorge Salaverri can always find a local who will take you out in a canoe.

Cayos Cochinos (Hog Keys), five miles northeast of La Ceiba, are the nearest and least developed of the Bay Islands. The Plantation Beach Resort, a newly remodeled quirky little inn with a great bar, offers deep-sea fishing, diving on the barrier reef, and snorkeling in the Cayos Cochinos Marine Reserve ($599 per person per week, includes food and all diving; 800-794-9767; ). The resort also has sea kayaks, free to guests and perfect for touring this compact island chain, including Cayo Chachauate, a traditional Garifuna fishing outpost.