Amundsen Schlepped Here

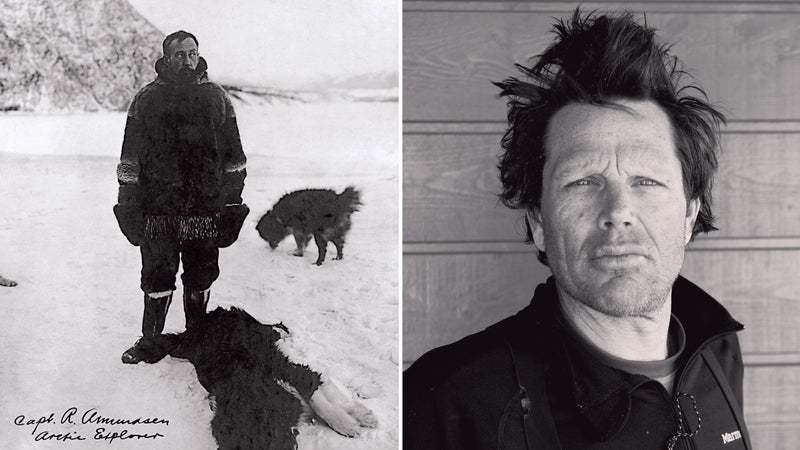

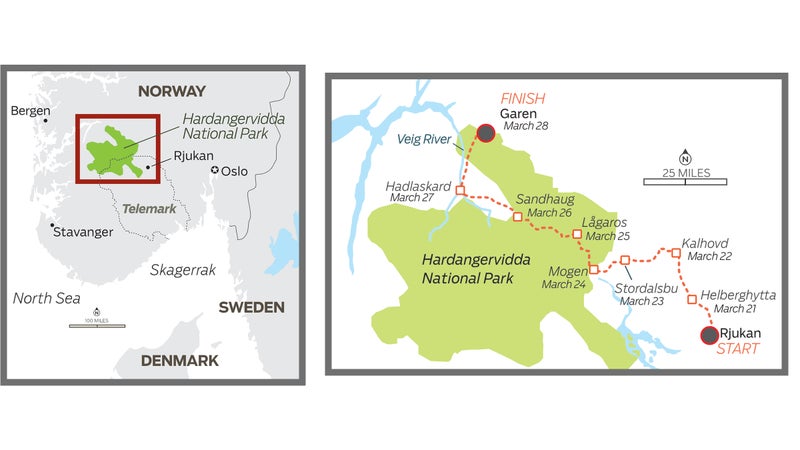

Norway's forbidding Hardangervidda Plateau nearly killed Roald Amundsen when he attempted a ski traverse in the winter of 1896. But the failure set him on a path of training, study, and exploration that led to his historic conquest of the South Pole. To commemorate the 100th anniversary of that feat, Mark Jenkins and his brother Steve skied the route, an epic challenge that even now can prove deadly.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

Lost in a building whiteout on a frigid day in 1896, encrusted in ice, the two Norwegian brothers finally stopped skiing. Disoriented and directionless, Roald and Leon Amundsen decided to bivouac. They dropped their immense backpacks, stepped out of their seven-foot-long skis, and began burrowing into a snowdrift.

After digging two cramped holes side by side, like shallow graves, they crawled into reindeer-hide sleeping bags. They were shivering terribly. It was January in the mountains of southwestern Norway, when snow and wind, darkness and biting cold—the wolves of winter—conspire to kill the unprepared. Having skied for three weeks to traverse the 100-mile-wide Hardangervidda Plateau, wandering in blizzards and bivouacking repeatedly, they were thin and weak. Their stove was inoperable, and they hadn’t had food for two days.

During the night, blankets of snow piled up on them, at first muffling the sound of the roaring wind, eventually extinguishing it. The moisture from the brothers’ slow breathing iced the interiors of their snow holes. The snow’s weight nearly cemented their bodies in place. They were almost buried alive.

The next day, when 23-year-old Roald woke up, he found himself encased in ice, unable to move. But Leon, 25, having kicked off the snow through the night with berserk exertion, was able to escape. Only the tips of his brother’s boots were still visible. Leon dug frantically for more than an hour, pulling Roald out just before he asphyxiated.

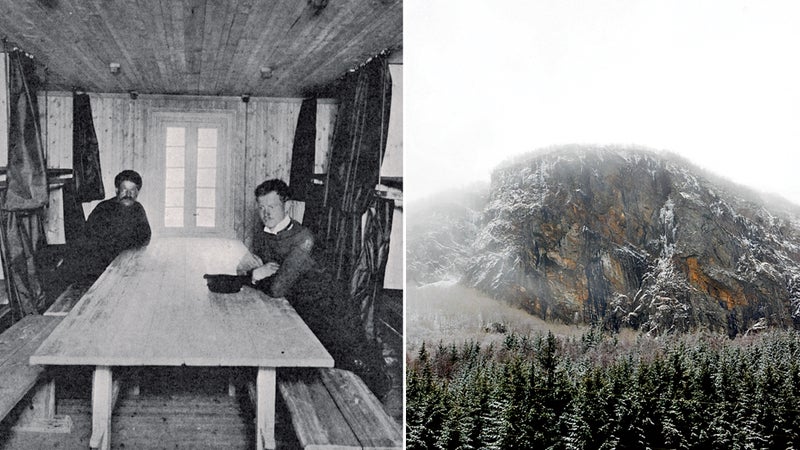

Later that day, the brothers skied south off the Hardangervidda. Frozen and hungry, they found their way to Mogen, a cluster of log cabins on the northern edge of a body of water called Vinjefjorden.

“They were saved by a farmer just over there,” says Kjersti Wøllo, sliding homemade reindeer sausages onto my plate and pointing through a steamed window at the spot. Wøllo and her partner, Petter Martinsen, operate the cross-country ski hut at Mogen, which they’ve opened early, in March, just for us. My brother Steve and I have come to Norway to retrace the Amundsen brothers’ journey across the Hardangervidda, partly as a tribute to our heritage (our mother’s side of the family is Norwegian) and partly to better understand the courage and drive that made Amundsen unquestionably the greatest polar explorer of all time. Mogen is halfway along our ski route. For four days straight, we’ve been grinding into 60-mile-per-hour headwinds.

“Amundsen gave the farmer a compass for saving their lives,” says Wøllo, a classic Norwegian beauty in her thirties, whose hair is pulled back in a thick ponytail. “His great-grandson still has it.”

The attempt was Amundsen’s second at crossing the largest mountain plateau in Northern Europe; the first, in 1893, ended after a 40-below open bivouac in which he nearly froze to death. The Hardangervidda had turned out to be almost unconquerably cold and storm-whipped: the perfect polar prep school. Amundsen would later wryly recall that his ski traverse “was as strenuous and dangerous as any of my following trips.… [T]he training proved severer than the experience for which it was preparation, and it well-nigh ended the career before it began.”

It is often the close calls of a man’s youth that set the course for his life. Ill equipped and ignorant, flush with youthful hubris, Amundsen would never again make such mistakes.

“���ϳԹ��� is just bad planning,” he would famously say. And yet it was by getting slammed in his own backyard that Amundsen found the direction of his life.

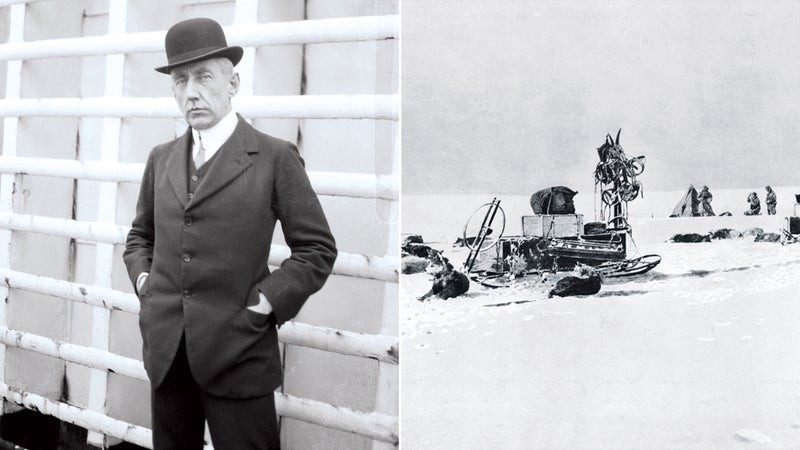

One hundred years ago, in the fall of 1911, a team of five Norwegians led by the 39-year-old Amundsen began skiing south across Antarctica, the harshest continent on earth. They looked like Inuits, clothed entirely in furs, mushing 52 Greenland dogs pulling four sleds. Some 500 miles west, a team of 15, led by 43-year-old Robert Falcon Scott, a British naval captain, began setting out for precisely the same absurd location: the South Pole.

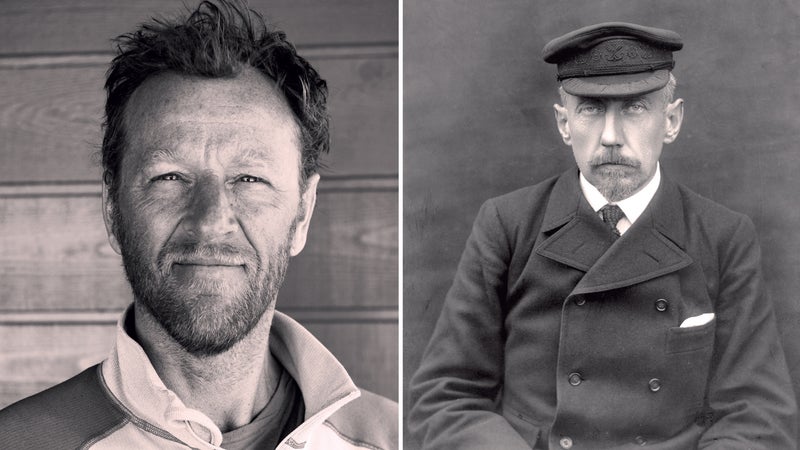

Scott’s team consisted of four men driving two motorized sledges, ten plodding behind sled-pulling ponies, and two on skis. As British author Roland Huntford recounted in his extraordinary 1979 double biography, Scott and Amundsen, this was the start of one of history’s last great adventure epics: a contest not simply between two men or two nations but between two philosophies.

Huntford was scathing in his critique of Scott, describing him variously as contradictory, confused, deluded, dramatic, irritable, and morose. Amundsen, on the other hand, drew his highest praise. “In the way an artist may be obsessed with his art,” Huntford concluded, “Amundsen was obsessed with exploration to the exclusion of all else.”

We all know how the contest ended. Amundsen got to the pole first and made it back safely with all his men. Scott also got to the pole—34 days after Amundsen—but didn’t make it back alive, dying of starvation with two other men in a forlorn tent 130 miles from base camp.

Having studied and experienced polar exploration throughout my adult life, I’m convinced that Huntford’s tough, controversial take on Scott got it right, but that doesn’t mean I don’t have respect for the Brit. Scott and Amundsen were both courageous men, equally committed to their cause. Both had larger-than-life egos that could lead other men to sublime achievements or bring them unimaginable suffering. But their styles couldn’t have been more different. Amundsen was a brilliant tactician and an exhaustive strategist, Scott a rigid officer and obdurate romantic who failed to understand that the strategies of travel and survival developed by the Inuit were the keys to success.

Both men served long apprenticeships en route to their destinies. Amundsen was born into a wealthy family of ship captains, the youngest of four brothers. He spent half his wild childhood skiing in the rugged fjords and deep forests around Christiania (now Oslo), the other half in shipyards and on the ocean. His father, a ship captain, died at sea when Amundsen was only 14. Amundsen attended university to appease his mother, but he had an intensely pragmatic, rational mind that was well suited to a life outdoors and incompatible with the classroom.

Scott was born into a wealthy family of naval officers, with four sisters and a brother. He was a sickly child, gently teased by his sisters, and at 13 he entered the Royal Navy as a cadet. An exceptional student, especially in mathematics, Scott went to sea for four years, returned to naval college, then went to sea again, sailing around Cape Horn.

Amundsen’s heroes included a fellow Norwegian, Fridtjof Nansen, a fabled explorer and the first man to ski across Greenland. Nansen was an ethnologist before the word existed and learned how to survive on the ice from the Inuit, almost reaching the North Pole in 1895.

Scott cast himself in the mold of the tragic British hero Sir John Franklin, a dogmatic, siege-style explorer who perished in the Arctic in 1848 with all 128 of his men, starving after his two ships became hopelessly trapped in ice. When Scott was made an officer, the Royal Navy had ruled the world’s seas for more than a century, but it had been gradually weakened by bureaucracy and nepotism. Scott wanted to be the man who restored that glory: he was known for his sly ambition, academic ability, and deep desire for promotion.

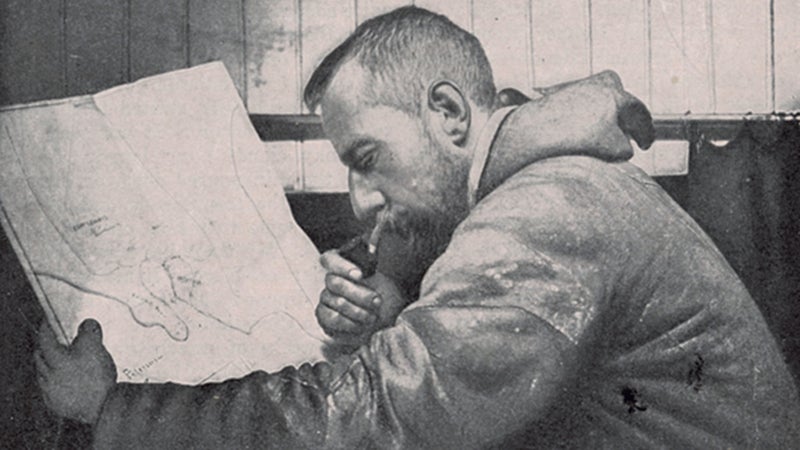

Amundsen decided as a teenager that he would become a polar explorer and never wavered, preparing himself in every way and signing on to a polar seal-hunting mission in 1894. He subsequently spent two years exploring the edges of Antarctica, then another three years, 1903–06, in the Arctic on a quest to become the first to sail from the Atlantic to the Pacific through the ice-choked Northwest Passage. He not only completed this harrowing mission but became the second explorer to reach the magnetic North Pole.

It was during this expedition that Amundsen learned about dogsledding and igloo building from the Netsilik Inuits. What he saw impressed upon him the hard facts of polar travel: fresh meat could prevent scurvy (a disease caused by a lack of vitamin C), dogs and sleds were perfect for the poles, skis were fast and efficient over great distances.

In 1907, Amundsen published The North-West Passage, two unheralded volumes of straight, unadorned prose in which he underplays risk, takes struggle in stride, and heralds the primitive winter survival skills of the Inuit as supreme. Like Nansen before him, Amundsen was far ahead of his time, having the genius and openness to master the indigenous culture’s ancient survival skills—an ability not simply ignored but often disdained by other explorers of the day.

Scott also spent three years, from 1901 to 1904, probing the edges of the Antarctic. Afterward, he wrote an adventure classic, The Voyage of the Discovery, a man-against-nature tale that became a critical and financial success. And yet, regarding polar travel, Scott’s national prejudices led him to conclude just the opposite of Amundsen: he insisted on the nobility of man-hauling sledges versus the efficiency of dogsledding, was convinced postholing on foot worked better than gliding on skis, and refused to believe that fresh meat prevented scurvy.

At the time, the South Pole was the last great prize for explorers. English captain James Cook had been the first to sail across the Antarctic Circle, in 1773; his countryman Edward Bransfield the first to set foot on the continent in 1820; and another English captain, James Ross, the first to chart some of its coast. Ernest Shackleton, who had been with Scott in the Antarctic on board the Discovery in 1901–04, led his own ill-fated expedition to the South Pole, getting within 97 miles in January 1909 before turning back and almost dying of starvation during his retreat.

Later, in the summer of 1909, the American Frederick Cook, thought to be dead, suddenly emerged from the Arctic, claiming to have reached the North Pole in April 1908. Two weeks after that, American Robert Peary claimed to have done the same in April 1909. Newspapers were abuzz for months.

Today it’s generally accepted that both Peary and Cook were lying, but at the time their claims changed the game completely. Scott and Amundsen, archrivals, immediately set their sights on the South Pole. The race was on.

At 845,595 acres, Hardangervidda National Park is the second-largest wilderness area in Europe. When the Amundsens tried to traverse it, they winter camped, spending only one night in a hut called Sandhaug. Today, thanks to the Norwegian Trekking Association, there are two dozen huts on the treeless, wind-scoured plateau.

Using Amundsen’s description of his ski trek and a topo of the Hardangervidda, Steve and I plotted a roughly 100-mile route from southeast to northwest, passing by eight huts. Two were staffed and served meals; the other six were self-service dwellings stocked with food, fuel, and blankets. Which meant that we could conceivably do a very light ski tour—no tent, no sleeping bags, no stove, no cookware, no food.

“But what if we get lost in a whiteout?” Steve asked. “Or get hurt, or move slow, or for whatever reason don’t make it to the next hut? We’ll freeze to death.”

He wasn’t exaggerating. Three weeks before we left, four Germans skiing hut to hut on another trail in Norway were found dead. Swallowed by a snowstorm, they froze within a mile of shelter. Four years earlier, two Scottish skiers attempting to cross the Hardangervidda hut to hut had been caught in a storm and died of exposure right on the marked ski track.

In the end, we each brought a foam pad and a paper-thin bivy sack, plus one shovel—just enough to dig in and survive a night out if necessary. Throughout the winter leading up to our trip, Steve, a headhunter in Denver and a former high school cross-country ski racer, hit the NordicTrack each morning at four; I skate-skied every day in Wyoming. Knowing that we had to be swift and smooth—or else—we toured together some weekends, through the worst conditions we could find, continuously testing and refining our gear choices.

Steve was expecting calamity and prepared for it. The Hardangervidda traverse didn’t strike me as any more difficult or dangerous than some of my other trips—skiing across the heart of Greenland with a Norwegian and Swedish expedition, circumnavigating Yellowstone for a month on skis—so I arrogantly expected an easy eight-day tour.

The first five minutes on the Hardangervidda disabused me of this. The wind was so fierce, it had stripped much of the snow off the tundra. What snow remained was ice, and we were obliged to immediately stretch on our skins to avoid being blown straight backward.

“What’d I tell you!” Steve screamed, grinning ear to ear.

Amundsen had the genius and openness to master the Inuit’s ancient survival skills—an ability often disdained by other explorers of the day.

The first hut, Helberghytta, was empty and cold when we arrived. The cabin is named after Norway’s most famous World War II resistance fighter, Claus Helberg, and its walls are lined with photographs from the secret mission he’d been part of to destroy a Nazi plant near Telemark that produced heavy water, an essential ingredient in the production of nuclear weapons. We fired up the woodstove, boiled canned reindeer meatballs we’d found in the pantry, burrowed under five layers of woolen blankets like kids in a fort, and felt deeply grateful not to be camping.

The next day, the headwind was preposterous. We were repeatedly knocked off our feet, as if we were being slugged by an invisible boxer. At lunch we had to sit on our packs, backs hunched against the wind, lest they be blown away.

“Can’t imagine having more fun,” Steve shouted through his hood.

It took us more than eight hours to cover 14 miles to the Kalhovd hut. There we found 16 Norwegians huddled around the woodstove, drinking tea and waiting out the storm. When our faces thawed enough for us to speak, they were shocked.

“Americans! Why woot you come here to Norvay?”

I mentioned my obsession with Amundsen, and Steve explained that our mother’s maiden name was Smebakken—“smith on a hill.” They nodded but still looked confused, clearly wondering why two people from the land of obesity would choose to ski through a storm in long, lean Norway.

The next day, the wind remained ridiculous. The Norwegians altered their plans and ended their trip, going downhill with the wind. Steve and I did the opposite, skiing due west across Kalhovdfjorden, directly into the gale, not speaking and stopping only once to wolf sandwiches and energy bars while hiding behind a boulder.

It took us seven hours to go 14 miles. Without skins, despite the fact that the terrain was flat, it would have been hard to reach the next hut, Stordalsbu.

“Amundsen would be proud,” Steve shouted as we arrived at the snug, clean, well-built Norwegian cottage. I made a fire while he cooked. My brother was lighthearted and talkative, unfazed by the unbelievable weather; I was both exhilarated and exhausted.

The next morning, we crossed a pass in the first couple hours and began sliding downhill into a roaring opaqueness. When the terrain leveled out, we guessed we were somewhere near Lake Vråsjåen but needed bearings. As I was holding the orienteering compass over the topo and trying to triangulate, the wind ripped both map and compass from my hands. They disappeared in the maelstrom. Only partially unnerved, Steve pulled out an extra compass and spare maps and we huddled together.

“We’re off course!” I yelled.

He looked worried. He knew that if we were really lost, we probably wouldn’t survive a night out.

Following a hunch, we made a 90-degree turn to the south. We’d skied half a mile when the clouds cleared just long enough for us to get our bearings, locate the trail again, and identify our next pass. I laughed with relief, and Steve spanked his ski poles over his head.

We ascended the pass slowly, cowering behind rock outcrops where we could. Dropping down the other side was lovely at first. We telemarked over icy meadows and along a wiggling creek. But soon the topography tipped and we found ourselves in a steep defile. For hours we carefully downclimbed frozen waterfalls, zigzagged through birch trees, plowed into snow up to our waists, and cursed the Norse gods.

We reached the Mogen hut deeply grateful not to have broken a leg but well aware that the remaining trip would be both dangerous and challenging. Though there was a trail on the map, there wasn’t one on the landscape: almost every day we were out, we had to navigate with map and compass through a howling white wilderness.

Amundsen and Scott arrived in the Antarctic in January of 1911, and each team knew that a historic contest was under way. Hundreds of miles apart, both teams built elaborate base camps on the Ross Ice Shelf and prepared to winter over. A single push to the South Pole—1,400-plus miles round-trip, with a dangerous haul over high passes through the Transantarctic Mountain—was impossible, so each team spent the Southern Hemisphere’s autumn ferrying supplies to depots along their respective routes. When winter set in—June through August—darkness descended, and temperatures dropped to 50 below.

Amundsen’s men, working in well-crafted snow caves, were urgently industrious through the dark season. They tested and altered their ski boots three times, each man cobbling his own boots to conform precisely to his feet to prevent frostbite and blisters. Their fur clothing was repeatedly evaluated on trial runs and then retailored by each member to fit perfectly, eliminating chafing. The men used a lightweight wind cloth to make tents that were nearly half the weight of canvas ones, then dyed them black with shoe polish and ink powder, for three reasons: to make it easier to find the tents in a whiteout; to provide rest for weary, snow-seared eyes; and to soak up warmth from solar radiation. In the snow-walled woodshop, the team’s craftsman, Olav Bjaaland, redesigned their dog sleds, cutting the weight from 150 pounds each to 50. Bjaaland, a champion skier, fashioned custom skis for each team member.

Scott was satisfied with his wool-and-cotton clothing and confident in his ponies’ ability to plow through snow pulling heavy sleds. The English expedition did not refine its systems. Scott believed courage trumped adversity and that character, not craft, would carry the day. In their base camp at McMurdo Sound, he and his men squandered the winter on esoteric academic lectures, amateur theater, soccer, and letter writing.

For Amundsen, nothing had been left to chance. Pemmican was weighed down to the gram, biscuits (more than 40,000) were counted individually, seal meat was laid in depot larders, sled compasses calibrated, dogs fattened. He had learned from the Inuit that deliberately courting danger was immature, if not immoral.

Scott was a big-picture man with visions of grandeur, and he left the details to others. Besides, for the first 400 miles he would literally be following in Shackleton’s footsteps. To set his farthest-south record, Shackleton and three companions had plodded on foot, man-hauling massive sleds. Scott intended to do the same after using ponies and dogs for part of the route.

From the start, Amundsen moved quickly and smoothly. He could barely control the exuberance of his dogs, and the men could sometimes ride on the sleds rather than ski. His teams typically covered 12 miles in five or six hours, then set up camp, devoting the rest of the day to rest and recuperation. If the weather was nasty they built igloos. In the fall, they had marked their depots with wide lines of flags in case they veered off course, so that even in storms they easily found their resupplies of food and fuel. For the Norwegians, all of whom were excellent cross-country skiers, it was a grand jaunt. A big ski tour.

Scott’s two prototype snowmobiles (a third fell through the ice while unloading) had not been properly tested during the winter, and few spare parts had been cached, so they broke down and were abandoned after five days. The ponies, sweating all over their bodies, suffered grotesquely, Huntford wrote, their backs and flanks often plated in ice. Naturally, their sharp hooves punched holes in the snow. They were often wading up to their trembling knees, sometimes up to their freezing, huffing chests. Halfway to the pole, their fodder gone, the ponies were shot. From that point on, man-hauling began.

It was a given on both expeditions that some of the draft animals would be killed en route. Amundsen put down any of the sled dogs that came into heat, wouldn’t pull, or became too belligerent, feeding them to the remaining dogs, his team, and himself. At one point, after slogging over the Transantarctic Mountains—a massive east-west chain with peaks of up to 15,000 feet—Amundsen slaughtered half his remaining dogs to supply both men and animals with enough meat to survive the final push to the pole and the return trip. The journey back, when men and beasts were mentally, physically, and spiritually fatigued, was even more crucial than the push out.

Having determined on previous polar journeys the precise daily nutritional needs of both man and dog, Amundsen had ten times the reserves of food at each depot as Scott. By skiing only half a day, Amundsen’s team retained strength, vigor, and morale. Scott drove his team like he drove the ponies, his men pulling in harnesses 12 hours a day. They inevitably became weak, emaciated, and demoralized.

At Mogen, Wøllo and Martinsen fed us so well—and regaled us with so many remarkable stories about the pleasures of Norwegian life—that we might have given up our traverse right there. Thanks to a wealth of oil and natural gas, the government has accumulated the second-largest rainy-day fund on earth, more than $500 billion. Every citizen has guaranteed government health care for life and a full pension. Unemployment is low, and there’s essentially no poverty.

“I think I could live here,” Steve said dreamily as we were falling asleep in our bunks. Alas, the next day we had to ski away.

The wind had at last abated, replaced by below-zero temperatures. We pushed back up onto the central plateau, stopping only for lunch and swigs of hot cloudberry tea. The snow was brittle and the landscape bewilderingly featureless—in all directions, there were snow-clad hills of identical height and shape. We set a map bearing and followed it precisely, deviating only to avoid steep ascents or descents.

When we reached the Lågaros hut, in midafternoon, it was so buried we had to dig it out to get in the door. We assumed we would have it to ourselves, but soon we heard shouting. Peeking out the frosted windows, we couldn’t believe what we saw: three kite-skiers literally sailing in from nowhere. They dropped their packs beside the hut and then continued to kite-ski just for the fun of it, jumping and carving, sweeping in vast loops across the landscape.

When they finally came inside, they were jubilant. They were Norwegian, of course: two brothers and a woman. They’d skied 28 miles that day and still had energy enough to play. We’d come just 11 miles and were whipped. One was a soldier who had just returned from a year in Afghanistan; the other two were medical students. This was their third attempt to cross the Hardangervidda.

“The other times, the wind didn’t cooperate and we had to trudge along on skis,” one said with a knowing grin.

They’d spent three years testing different skis and kites and knew exactly what they were doing. They were also going with the prevailing winds rather than against them, as we were.

“Total traverse of the Hardangervidda will take us about three days,” the woman offered, almost ashamed to admit the efficiency of their trip to a couple of cross-country masochists who would ski for eight days to cover the same distance.

They slept in the next morning, knowing they could fly another 20 to 25 miles in a matter of hours. Meanwhile, Steve and I slogged on.

The snow was rough and the landscape burning white. It was like skiing across a desert of sand dunes. With the wind down and navigation unnecessary, we knocked off the 16 miles to Sandhaug, the next hut, in a few hours.

One hundred and fifteen years ago, the Amundsen brothers had spent a night in this very hut. Arriving early in the afternoon, we had time to catch up on our journals, sketch out our route on the maps, hoover an extra meal or two, and toast our toes over the stove.

“I’m not sure life gets much better than this,” Steve said before dozing off.

The headwind on the Hardangervidda was preposterous. we were repeatedly knocked off our feet, as if slugged by an invisible boxer.

That night another storm blew in, and it began building drifts around the cabin. Just as we were turning in, five middle-aged, not particularly fit Norwegians burst through the door.

“Vat are you doing here?” one of them asked snootily. But they were more than happy to suck down all the snow we had melted and dry their soaked socks over the well-stoked stove.

The next day we were gone before they got up. It was snowing and blowing miserably. Within the first hour of skiing, visibility dropped until the sky and the earth fused into a single miasmic substance. At one point, looking down, I spotted two black dots far below me. Staring through depthlessness, I couldn’t tell how far away they were. Five yards? Five hundred? I backed away from the gaping abyss only to realize that the distant dots were the tips of my skis.

Without depth perception, it became difficult to balance and impossible to move in a straight line. We were blindfolded by the whiteout ten miles from our next hut. We had to stop.

“Have gone completely blind all day,” Amundsen recorded in his journal on December 5, 1911. “[T]hick snowfall more like home.” He and his team still skied 12.5 miles. The next day was no different, but Amundsen’s team made their standard distance no matter what.

Scott, materially and mentally unprepared for such conditions, either didn’t move on bad days or trudged moderate distances that required unconscionable suffering, his men straining to man-haul their monstrous sledges.

As Amundsen closed in on the pole, Scott was hundreds of miles behind. Neither knew of the other’s position, which caused Scott enormous anxiety. He pushed himself and his men sadistically. There were days when both Scott and Amundsen made the same mileage but Amundsen did it in half the time, economizing on effort and riding the sleds when possible. Scott all but killed himself and his men.

On December 14, 1911, Amundsen and his four teammates made it to the South Pole. “And so at last we reached our destination and planted our flag on the geographical South Pole … Thank God!” he wrote in his journal. His focus on his men, he stated that his teammates displayed the qualities he most admired: “courage and dauntlessness, without boasting or big words.” He and his skiers had been in the Antarctic almost a year and had been skiing toward the pole for more than 50 days, covering some 700 miles. Aware of the need for proof, the Norwegians spent three days mapping 24 sextant readings to make absolutely certain they were precisely at the bottom of the earth. They left a sled, a tent, and a cheeky note of welcome to Scott, then headed home.

Scott and four men (all the others having been sent back along the way, fortuitously) arrived at the South Pole more than a month later, cadaverous, malnourished, tired, and weak. They found Amundsen’s tent and his note. Wrote Scott: “Great God! This is an awful place and terrible enough for us to have laboured to it without the reward of priority.”

“Do you have any idea where we are?” Steve yelled.

“No! But I know where we’re going,” I screamed back.

The evening before Steve and I got caught in this latest whiteout, at Sandhaug, I’d been listening to the snow beating against the windowpanes like the wings of a frightened bird. Concerned about the next day’s travel, I’d calculated four consecutive bearings in the warmth of the hut. There were three empty cabins between us and our next destination; the bearings shot like arrows from one to the next.

Abandoning any pretense of seeing where we were going, Steve and I set off in the direction of the first bearing. After skiing blind for five minutes, we stopped, held the compass directly over our skis, and found that we were ten degrees off course. The wind was too strong to ski without both poles, so we resorted to rechecking our bearing every 50 paces. It was tediously slow going, but we hit the first intermediary cabin dead-on. A drink, an energy bar, and onward.

We made the next hut by lunch. It was half buried, so we dug out a hole under the eaves, laid down our foam pads, ate deliberately, and ignored the swirling snow. On the map we were halfway to our goal, although we had been trapped in clouds all morning and had seen nothing but white on white.

We never found our third landmark cabin—it must have been entirely buried. At one point, the clouds cleared and Steve pointed out a ridgeline.

“Maybe a click away?” he shouted. But the landscape was still playing tricks on us; it was three times that far.

At the end of the day, we were traveling along a steep hillside, beginning to question ourselves, when our destination—the Hadlaskard hut—appeared out of nowhere to our left.

It was our last hut on the Hardangervidda. We feasted on reindeer stew, crackers heaped with Nutella and cheese, and thick squares of Norwegian chocolate. Since we were the only people in the hut, we dragged blankets from the cold bunk rooms, lay down on the couches next to the woodstove, and slept so well we snored.

As if the Norse gods were finally convinced that we were worthy of our little dream, the wind stopped blowing the next day—our last—the sun came out, and Steve and I slid effortlessly along. We glided atop the snow-covered Veig River, dropping into pockets of birch trees with summer cabins sprinkled among them. As we marched up over our last pass, it started snowing lightly. Warm, big flakes and no wind. We slid north off the Hardangervidda hardly poling, completing the traverse in Garen.

But now it didn’t feel right to stop. After more than a week of abysmal weather, the conditions were suddenly straight out of a fairy tale, twinkling snow falling like goose down. We decided to do a big victory loop. Striding in rhythm, brothers in silent unison, we skied through the forest into the twilight.

As Roland Huntford clearly laid out in Scott and Amundsen, Scott was transformed into a hero by the English press when he should have been pilloried. On his expedition’s ignoble struggle from the South Pole back to camp, petty officer Edgar Evans was the first to die, pulling to the last, collapsing in his harness. Cavalry captain Lawrence Oates was next, his feet so frostbitten they were gangrenous. On the morning of his 32nd birthday, Oates crawled from the tent and limped into oblivion. Scott was still keeping his journal, writing for posterity, penning vainglorious letters of farewell. Marine lieutenant Henry Bowers, chief expedition scientist Edward Wilson, and captain Robert Falcon Scott, all skeletal and badly frostbitten, died in their tent in Antarctica sometime after March 21, 1911.

After reaching the South Pole, Amundsen and his team easily cruised back to base camp, covering 700 miles in just six weeks. In all, they had skied 1,400 miles in 99 days. No one had died; hardly anyone had been sick. There was some frostbite, but no one lost fingers or toes. Amundsen had done everything possible to remove drama and danger from his expeditions, and for that he was, in a strange but tangible way, punished. Despite the fact that his South Pole expedition was the apotheosis of elegance and efficiency, arguably the finest expedition ever accomplished by man, he would be all but forgotten outside of Norway in the decades after his death, which came in 1928, when he perished in a plane crash, probably over the Barents Sea.

Huntford, who did as much as anyone to restore Amundsen to the adventure pantheon, thought his death was both a waste and a fitting end. Amundsen had been on his way to help rescue an Italian polar explorer, Umberto Nobile, who had disappeared during an airship flight to the North Pole. Nobile was rescued by someone else, so Amundsen could have stayed home. But for Huntford, it was a strangely appropriate exit.

“His end was worthy of the old Norse sea kings who sought immolation when they knew their time had come,” he wrote. “It was the exit he would have chosen for himself.”