“I saw the old jalopy,” said a bony stranger sitting across the table from me in a coffee shop in our ancient Southwestern city. He was sporting an armadillo-shaped bolo tie and a cowboy hat, and he squinted like a B-movie gunslinger about to draw his Colt .45. “I placed my fingers in the bullet holes.”

Between tugs on a grande latte, the old compadre described a black 1922 Dodge convertible with four on the floor and wood spokes. The owner had been none other than Francisco “Pancho” Villa, the Mexican outlaw-turned-revolutionary who championed the poor by helping to topple the brutal despot Porfirio D├şaz in the Mexican Revolution of 1910, and evaded U.S. troops after a murderous cross-border foray. In fact, he allowed, this was the very set of wheels Villa had been driving when he was assassinated in 1923 by seven mystery gunmen. According to the coffee-shop cowboy, who’d set eyes on the vehicle in the late 1970s, the old beater was sitting up on blocks in the backyard of a house that belonged to Villa’s widow on the outskirts of the city of Chihuahua, Mexico.

I’ve always been intrigued by this mythical, sombreroed hero. And northern Mexico, the desolate land where Villa lived, has been the scene of several harebrained “expeditions of discovery” of mine over the last ten years. Now Pancho’s car was all the excuse I needed to head south again for some desert mountain biking in the depths of nearby Copper Canyon. I packed my pickup and before long I was crossing the Rio Grande at El Paso and rolling down Mexico Highway 45, headed into a roiling sea of dust devils in the blistering mesquite desert in search of an old metal hunk of history.

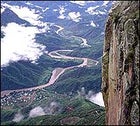

The state of Chihuahua is Mexico’s Texas: The skies are big, and the people are proud. But there is one significant difference between these neighboring landsÔÇötopography. Chihuahua’s flat, notoriously dusty deserts and high plains, dotted with sprigs of pi├▒on, are bisected by the 9,000-foot peaks of the Sierra Madre Occidental, which starts at the U.S. border and runs south, parallel to Mexico’s Pacific coast, and ends near Mexico City. I planned to follow the spine of the range south to an isolated area called Barrancas del Cobre, Copper Canyon to English speakers. The name refers not to one particular gorge, but to a 25,000-square-mile region that includes seven river-carved canyonsÔÇöthe Batopilas, Candamena, Chinipas, Septentrion, Taraecua, Urique, and Verdes. Four of these are more than 5,900 feet deepÔÇödeeper than Arizona’s Grand Canyon. Besides being the largest canyon system on the continent, Copper Canyon also happens to be riddled, as I’d discovered on previous trips to the region, with amazing singletrack, created by the Tarahumara Indians who live there.

Even more than Americans, Mexicans have long been enamored with outlaws like Villa. Born Doroteo Arango in San Juan del R├şo in the northern state of Durango in 1878, Villa committed his first recorded crime when he was still in his teens, killing a ranch owner who had assaulted his sister. Afterward he fled to the Sierra Madre, became a bandit, and grew famous for his ability to elude the law. Americans probably know Villa best for his brutal raid on Columbus, New Mexico, in 1916ÔÇöa response to the U.S. government’s support of one of Villa’s political opponentsÔÇöin which 18 Americans were killed. The U.S. Army chased Villa deep into Mexico, but never caught him.

My first brush with the ghost of Villa occurred 300 miles south of the border in a tequila bar in Creel, a logging town of about 4,000 in the Sierra foothills where Villa hid during the 1910s. Here, a burly truck driver told me that Villa still lives on in the rugged individualism of the people of el norte├▒o, northern Mexico. Here, you still see bumper stickers that read “Viva Villa! Viva Mexico.”

Creel is the northern gateway to Copper Canyon; Batopilas, 85 miles south, is the region’s southernmost town. Today the canyons are mostly inhabited by the Tarahumara, who are known for having maintained their ancient traditions of dwelling in caves, growing corn, and weaving pine-needle baskets, as well as for their ability to run amazingly long distances.Over the centuries, the Tarahumara have fended off the invasions of Spanish conquerors, Mexican colonizers, miners, pot growers (parts of the area are now home to a bounty of marijuana fields and cranky Mexican drug lords), and logging companies. The Mexican government now wants a finger in the Copper Canyon land-exploitation pie, too. A $385 million federal project, dubbed the Copper Canyon Master Plan, is already in the works to build enough roads, lodges, and cultural centers to transform the area into a mass-market vacation spot by 2006. (Currently, Copper Canyon draws about 370,000 tourists each year, most of whom merely pass through Creel on the Chihuahua al Pac├şfico Railway.)

Itching for new trails to explore, I rented a mountain bike from one of Creel’s two bike shops. Then i introduced myself to a skinny local kid named Alex Antwan, who was spinning wheelies up and down the main street, and talked him into going for a ride. We criss-crossed mesas, darted into narrow canyons, and rode through some of the largest old-growth stands in the Americas, which are home to wolves, black bears, pumas, and even grizzleis. We drank water from springs and rested inside abandoned Tarahumara caves. When we returned to Creel a few hours later, we sat beside the train tracks and guzzled Mountain Dew. That night, over burritos at Case de Margarita, a packpackers’ hostel, I plotted out my next moveÔÇöa descent by rickety bus to the bottom of Batopilas Canyon.

The town of Batopilas (population 1,200) is an oasis at the bottom of the 20-foot-wide gorge, with shimmery, coppery-colored walls shooting straight up over it. Mango, lime, and papaya trees grow along the river and on the town’s main street. Saguaros stand at attention on the hillsides. The chirps and squaqk of birdsÔÇöparakeets and rare military macaws, among othersÔÇöpierce the humid, sleepy afternoon air. From here you can hike to adjacent Urique Canyons, but claustrophobes beware: Urique feels like the bottom of a deep wellÔÇöalbeit one with fig trees, orchids, palm trees, cubby brown trout, and VW Beetle-sized rocks. After a few days hiking the steep, white-dirt trails, swimming in the cool eddies of the river, and exploring abandoned gold mines by mule, I started getting antsy to find Poncho Villa’s car, and Chihuahua was a full day’s drive east from Creel. It was time to hit the road.

When I pulled into Chihuahua, a city of about 615,000, the sun was pounding down like a heavy fist. Chihuahua was Villa’s command center when he served as general of the northern army in the 1910s. Today it’s a beehive of speeding clunkers, honking horns, and people rushing off to ranching, mining, factory, and timber-industry jobs. I dumped my gear at a motel and hopped a cab for the outskirts of town, looking for the car. When my cowboy friend visited all those years ago, Villa’s widow had been alive. He had stood gazing at the old Dodge while she told the story from Villa’s fateful final day. It was a clear morning in 1923, and Villa was driving from the bank in Parral, 112 miles south of Chihuahua, to his ranch about an hour away. As he rounded a corner, seven gunmen opened fire, pumping the car and driver full of bullet holes. To this day, nobody knows who the gunmen were.

My cabbie knew exactly where to go. “Pancho Villa’s car,” he said. “Viva Villa! No?” As he dropped me off on the southeast side of town, I realized that the old house couldn’t be the well-kept secret it had been 20 years earlier. The widow was long dead, and the government had renovated the house and turned it into a museum, complete with a gift shop full of cheap-looking Villa memorabilia. I paid my 50 pesos and headed for the backyard, where the car sat, gathering dust. But something troubled me about the way it looked. Despite the well-worn (and non-bloodstained) upholstery, the paint sparkled like new and the wooden spokes were polished to a shine. More telling, there were only a handful of bullet holes in the side of the car, not 150, as the museum’s history books touted. I had driven 500 miles across deserts and over mountains to get a peek at this car, but now I wasn’t even sure if it was the real thing. Then it struck me: The late great Pancho Villa had been Elvis-ized.

Whether you plan to follow in the footsteps of famous outlaws or make new tracks in Copper Canyon’s unspoiled wilderness, here are a few things you’ll want to know.

WHEN TO GO

The rims of the canyons experience seasonal weather changesÔÇöfrom around 70 degrees Fahrenheit in the summer to freezing temperatures and snow in the winterÔÇöbut the canyon floors are almost always hot. They’re at their coolest, about 65 degrees, from October to May.

GETTING THERE

El Paso and Tucson are the two stateside jumping-off points for Copper Canyon road trips. If you drive your own car, you’ll need insurance from a U.S. company that specializes in car insurance for Mexico, such as Sanborn’s Mexico Insurance (about $80 per week; 210-828-3587), based in San Antonio, or San Diego&150;based Anserv Insurance Services ($35 per week; 800-654-7504).

STAYING THERE

In Creel, I stayed at Casa de Margarita (011-52-1586-0045), a backpackers’ haven. A bunk in a shared room costs $5 per person, including dinner and breakfast; a private room costs about $20. In Batopilas, try the rustic adobe Hotel Mary for about $10 per person.

OUTFITTERS

Columbus Travel (800-843-1060), based in Columbus, Texas, operates multiday hiking excursions into the canyons with prices ranging from $1,050 to $2,190 per person. California Native International ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°s (800-926-1140) runs hiking trips for $590 to $2,060