CYCLING THE AEGEAN

Access and Resources

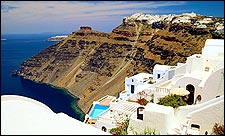

After a full day of biking, you’ll need little more than good conversation and a soft bed to make you happy. Three places that provide both: Pelikan Pansiyon, Kapikiri, Turkey (doubles, per night; 011-90-252-543-5158); Hotel Samos, Samos, Greece (doubles, per nigt; 011-30-273-028-377, ); and Hotel Adriani, Naxos, Greece (doubles, per night; 011-30-285-023-079, ). When island hopping in the Aegean, always double-check routes and schedules in port. For Greek ferry schedules and information, call 011-30-810-721-742 or visit . The whitewash wonders of Greece

The whitewash wonders of Greece ISLAND HOPPING IN GREECE AND TURKEY—ON TWO WHEELS

After 30 miles of biking along the jagged shores of the Aegean Sea, my seven companions and I rolled into Güllük, a sleepy port on the southwest coast of Turkey, about 600 road miles south of Istanbul. We walked into a bar, where a grizzly fisherman put down his glass of raki, an aniseed-flavored Turkish alcohol, and swaggered up to us, laughing. “Good!” he roared, gold teeth flashing, while plucking at my spandex tights. “�ձ������ü��!“—thank you—I yelled back, striking my best superhero pose. The bar erupted, raki spilling everywhere.

Güllük was our second stop on a trip that began at an ancient mausoleum in the Turkish town of Bodrum and ended ten days and 350 miles later at a nude beach on the Greek island of Naxos. A bike route that begins with crypts and ends with public nudity might seem odd, but in Greece and Turkey the ghosts of the past and the pleasures of the present happily coexist. Combining small portions allowed us to explore two cultures, and our criteria were simple: ocean views and ancient ruins.

After an olive-and-tomato breakfast in Güllük, we continued north and soon hit the Laba Dagi Mountains. We’d creep uphill, negotiating a steady slalom of sheep dung, and then race down the other side at 40 mph before hitting the next hill. At the end of our second 40-mile day we turned off the main road at a rotting wooden sign that indicated the village of Kapikiri. Instantly, trucks gave way to donkey carts, tinkling cowbells replaced blaring horns, and pantaloon-wearing women harvested vegetables in boulder-strewn fields. Dead tired, we checked into the Pelikan Pansiyon, a rustic inn just beyond the village’s medieval walls, and slept until we had to pedal off early the next morning. Over the next two days we worked our way 50 miles north through mountains and along ragged coast to the port town of Kusadasi, our launching point for Greece.

Greek ferries were made for bike touring. On a bike, you’re always the first on and the first off, blowing past waiting cars. On deck, you’re treated to an intimate view of Greek life: grandmothers unwrap tin foiled family feasts while teenage lovers neck behind the snack bar. After two hours, we stepped onto the sultry island of Samos, famous for its orchids and sweet wine. We ditched our panniers at the Hotel Samos, near the ferry terminal in the main town of Vathí, and set off to explore.

Ten miles over the island’s hilly spine we arrived in Pythagorio, where Pythagoras, the man who tormented generations of students with a2+b2=c2, was born 2,500 years ago. From Pythagorio we headed west, winding through olive groves and hill towns on one of the best 20-mile rides of our lives.

After sampling Samos, we jumped a ferry west to the Cyclades Islands and disembarked five hours later on Naxos, a windswept island that supplied the ancient world with marble. Checking into the Hotel Adriani was like dropping in on friends. The cheerful owners, father and son, welcomed us with a toast of kitron, a lemony elixir distilled only on the island.

The next morning, four of us biked 20 grueling mountain miles to Apollonas, on the island’s lonely northern tip, only to find that all the residents had left to attend a funeral. We headed back, parched and slightly delirious, stopping at a nude beach. With the cove to ourselves, we stretched out on the hot pebbles and soaked up the fading warmth of dusk. In that sublime moment I felt—like the bohemian writer Lawrence Durrell before me—”rocked and cherished by the present and past alike.”

Hiking the Dingle Peninsula

Getting lost—and found—on Ireland’s ancient tangle of trails

Rock on: a coastal vista along the trail

Rock on: a coastal vista along the trailThe path cut through undulating hillsides of green gorse and purple heather. Sheep danced away as we neared. We had walked alone for hours—lost—when two hikers appeared ahead. We prayed that they were shepherds who could guide us back to civilization, but instead we met two schoolteachers from New Hampshire, also lost. Our lyrical guidebook, The Dingle Way Companion, read, “Cross the field diagonally, clear a stile set in a stone wall and drop down through boughs of fuchsia, entwined as if in prayer. . . .”

Recreational hiking is still an emerging sport in Ireland, where working the fields once left little time for constitutionals. Nobody knows that better than Joss Lynam, the 78-year-old author and patriarch of Irish hiking, who led the push to expand the National Waymarked Ways (just Ways, for short), which link about 1,910 miles of ancient bog paths, goat spoors, and fisherman’s trails. “If you’re chasing sheep over the hills five days a week, you don’t want to do it on the weekend,” said Lynam. That’s changing. In 1991 there were only 12 Ways. Today there are 33. But Lyman was no help to us now, and in a late-afternoon routine that we repeated daily, we hitchhiked, wet, hungry, and happy back to our hotel.

There are no huts along the Ways, but farmers allow camping, and trails often pass through or near towns with hotels, hostels, and B&Bs. On this trip last fall, my wife and I fell for the village of Dingle and its cobblestone streets; blue, green, and orange row houses; and dark pubs. So instead of hiking the entire 95-mile Dingle Way, which hugs the perimeter of southwest Ireland’s Dingle Peninsula, we stayed for three days on the outskirts of town at spacious, modern Greenmount House, an inn with ocean views. We took daily hikes averaging 14 miles, crossing green fields and stark beaches. Mornings began with a buffet of smoked salmon and homemade breads and jams before we headed west from the inn through intermittent rain. We would survey Dingle’s harbor, looking for the wild but fish-begging dolphin named Fungi, then pick a direction and go.

On the flanks of 1,693-foot Mount Eagle, about five miles west of Dingle, we stood among the cattle and wildflowers, watching the morning mist rise to reveal craggy islands to the west and 3,000-foot Brandon Mountain to the north. We stopped to pluck blackberries. We stopped at the medieval ruins of Menard Castle and Celtic stone huts called clochain. We stopped to watch gannets dive from their cliffs into the water below, and we stopped to check the “guidebook.” Eventually we found a road and stuck out our thumbs.

On our final day, we walked through spongy, shoe-sucking peat bogs to the tip of Dingle Peninsula. Atop sandstone cliffs we looked down 500 feet to islets and caves. Later, when we were lost—again—we stumbled onto Kruger’s pub. After an hour of listening to the Gaelic tongue of farmers, we forged on, content to let the landscape lead the way. Finding our inn was a bit less important after the pub’s cool Guinness and hot whiskey.

Mountain Biking in Provence

Meet the Moab of France—sweet singletrack enhanced by olive groves and better wine

Access and Resources

The hiking guidebook Circuits Pédestres et VTT includes mountain-biking routes in southern Provence, from Mont Ventoux to the Mediterranean Sea. Gassou Shop is at 422 Avenue Victor Hugo (011-33-490-74-63-64). Another shop, closer to downtown Apt, is VTT Lubéron, 2b rue Amphitheatre (011-33-490-74-54-25). The outfitter Egobike (011-33-490-67-05-58) offers one- or two-day mountain-bike courses. Hôtel L’Aptois is at 289 Cours Lauze de Perret (011-33-490-74-02-02)., and Au Petit Saint Martin is at 24 Rue Saint-Martin (011-33-490-74-10-13). For general information, call the Provence Tourist Board in New York (212-745-0980). C’Est magnifique: the vineyards of Provence

C’Est magnifique: the vineyards of ProvenceAt some point along a meandering ridge trail called the Grande Randonnée 9, the thought took hold: The region around Apt, in southern France, is a kissing cousin to that mountain-biking mother lode, Moab. Both areas are sun-drenched convergences of startling geology, sudden inclines, and long vistas, crisscrossed with technical trails. Apt even shares Moab’s Mars-colored riding surfaces—the powdery, ocher-infused dirt of Provence glows as lustrous as Utah’s sandstone. It just hurts a lot less when you biff on it.

But I had to set my revelation aside when the GR 9 turned abruptly to the right, sauntered among the stone ruins of a castle, plunged down an ivy-laced ravine, and skirted olive groves. When the ride finished in a town with cobblestone streets so narrow my bike could barely pull a U-turn, Moab’s fast-food franchises and prefab motels seemed, well, an ocean and a continent away.

Like the Impressionist painters who moved to Provence for the astonishing intensity of its light, mountain bikers also find much to their liking here. With more than 300 days of sunshine a year and frost-free winters, Provence’s riding season is long and hassle-free. The widely spaced trees—cedar, oak, juniper, and eucalyptus—keep trail duff and deadfall clutter to a minimum.

I first rode Provence three years ago. Near Nostradamus’s hometown of Salon-de-Provence, I snuffled down singletrack brimming with rosemary and thyme. On my second trip, I ventured farther inland to the Parc Naturel Régional du Lubôron, 637 square miles encompassing the 11,500-person village of Apt, as well as winemaking estates, lavender fields, rugged slopes as high as 3,690 feet, and startlingly phallic ocher formations.

A stop at Gassou Shop, on the west side of town, got me pointed to Apt’s trademark playground, Le Colorado Provençal, a canyon six miles to the northeast. The Colorado Provençal ride is one of many possibilities; hundreds of miles of riding trails surround Apt. Ridable chemins (roads) and sentiers (trails) spider up, down, and over the 31-mile-wide Lubéron range.

Once at the canyon, I followed the yellow markings that denote mountain-bike-friendly trails, spinning up a gentle grade to the rim. Birdsong and golden light made the preserve’s wind-eroded dirt pillars appear celestial, but still damn weird. As in Arches National Park, cyclists are banned from pedaling sensitive formations; unlike in Utah, the sights loom yards, not miles, away. The seven-mile loop concludes with a rollicking descent.

Each evening, I returned to the affordable (about $40 per night) Hôtel L’Aptois, on Apt’s eastern edge, to prepare for French post-ride refueling. Among several unpretentiously good restaurants, Au Petit Saint Martin stands out: a romantic room inside the chef’s house, tucked into a labyrinth of backstreets that a certain automobile-obsessed nation would have bulldozed long ago. On Saturdays, Apt hosts a bustling outdoor market where your euros buy fresh cherries and criminally good $4 bottles of Côtes du Lubéron wine.

Eight days in Apt coated my bike with grit the same hue that Provence native Paul Cézanne used in his palette. Too bad that when I flew home, U.S. customs officials washed the bike to keep our shores free of hoof-and-mouth disease—I wanted to spread ocher dust all over home.

Paddling the Tromsø Archipelago

The search for an Arctic Eden beneath Norway’s midnight sun

The arctic landscape of Norway

The arctic landscape of NorwayCatch a break from the North Wind, paddle 24 miles, and trust the advice of a modern-day Viking named Bent, and we just might make it to Eden. That’s the plan as Tim Conlan, the leader of our sea-kayaking expedition, spreads his nautical charts out on the dune grass inside our lavvu, an indigenous Scandinavian tepee. Twig in hand, he sketches the route to a long, sandy beach on the island of Rebbenesøya. There, in a crescent-shaped bay, awaits Eden, or at least that’s what Conlan’s sailing buddy Bent indicated on the chart. And as we were besieged at our first campsite by voracious sheep, thwarted the next day by a headwind so fierce it took us an hour to paddle a mile, and kept off the water by heavy gusts on our third day, this idyllic campsite—beachfront property, with freshwater streams and majestic ridges—sounds like Valhalla. We agree to an early start (4:30 a.m.) and pray that the wind abates.

We’re four days into a ten-day kayak tour through the thousands of mountainous islands west of Tromsø, well above the Arctic Circle and about 1,100 miles north of Oslo. The Tromsø archipelago covers about 450 square miles, and the rugged coast reminds me of the High Sierra, only with the valleys flooded by the sea. The region’s wide fetches and channels leave us exposed to the wind, and our progress has been slow. In fact, by the end of the trip we’ll have managed only 64 miles of a planned 100. Fortunately, the hilarity of tackling language barriers and debates about everything from polar bears to taxes to Zimbabwe strongman Robert Mugabe will have gelled our international team during the wind-enforced downtime.

Ten of us—four Americans, three Swedes, a German, a Brit, and an Afrikaner-Canadian—signed on for this Nordic ramble with Crossing Latitudes, Conlan’s Bozeman, Montana-based guide service. For seven years, Tim and his Swedish business partner and wife, Lena, have led kayak trips south of Tromsø, threading the granite towers of Lofoten and island-hopping the skerries of Vester&3229;len. The Conlans wanted to know what’s around the next fjord, so they arranged this exploratory, as outfitters call trips they have yet to complete themselves and run with experienced clients to gauge feasibility.

Aside from paddling, we’ve played spirited matches of the Viking game kubb (think horseshoes with rocks) and hiked to the top of Haaja, a 1,600-foot peak with a dead-drop to the breakers below. Aside from the sheep incident, our campsites have been untracked, snug in the curve of dunes or perched on low bluffs, and we’ve taken full advantage of the midnight sun. Last night, sensing a lull after dinner, we hit the water and covered 18 miles between 9 p.m. and 1 a.m., all the while reveling in the strange, affecting glow. It may cause insomnia, but the midnight sun sustains you, too, as if you were a plant in bloom. The one thing you don’t want to do here is flip your kayak: The water is a frigid 50 degrees Fahrenheit.

It takes about seven hours of paddling over two days to get there, and then, finally, we surf a two-foot break into the deserted beach on Rebbenesøya, and Bent’s Eden is, well . . . fallen, but beautiful. Several detonated mines from World War II lie half buried in the dunes. We beachcomb and scramble up the ravines behind camp and drink from snowmelt streams that trickle through mountain birch. Scores of bright forget-me-nots, carnivorous sundews, and budding multe (cloudberries) crowd our feet. Above us, a sea eagle soars.

Conlan concedes he won’t rush to add Tromsø to his outfitted trips. Nevertheless, he’s considering a second Troms” exploratory trip for 2003, farther north, where the archipelago hides more-secluded coves of glacier-smoothed rock and sun.

Access and Resources:

Crossing Latitudes (800-572-8747, ). Offers guided kayak trips in Sweden and Norway. Wilderness Center (011-47-77-69-60-02, ) and the Vesterålen Padleklubb (011-47-776-12-40-73) in Troms” rent kayaks and/or provide transport for put-in and take-out. For relatively inexpensive lodging in Troms”, try Ami Hotel bed and Breakfast (doubles, $81-$93 per night; 011-47-77-68-22-08, ). For information, contact the Norwegian Tourist Bureau (212-885-9700, ). For backcountry planning, contact the Oslo offices of Den Norske Turistforening, the Norwegian equivalent of the Sierra Club (011-47-22-82-28-00, ).

The Power to Move You

More self-propelled adventures

(SKATING)

THE ELFSTEDENTOCHT // THE NETHERLANDS

The Elfstedentocht (meaning “11 cities tour” and pronounced however you see fit) ice-skating race covers a stupefying 124 miles over the frozen canals, lakes, and streams of the northern Dutch province of Friesland. Of course, to have a 124-mile race, you need 124 miles of ice—a winter-weather miracle that has happened only 15 times since 1906 (the last time in 1997). To guarantee your go at the course, forget the ice skates and try in-line instead. The race route is a clockwise loop from Leeuwarden, Friesland’s capital, past flower-filled meadows, pristine lakes, and quaint villages—particularly Hindeloopen, a conglomeration of windmills and clock towers. You’ll skate mainly on perfectly paved, wide-berth bike paths, and when you do have to mix with traffic, Dutch drivers will always brake for you. Nonetheless, if your plan is to tick off all 124 miles, sign up with Amsterdam-based Skate-A-Round (011-31-20-4-681-682, ), which offers self-guided tours of four or five days for about $123 and $237 respectively, including hotels and some meals (the five-day tour stops at more-expensive hotels and includes more meals per day). You roll solo but get the convenience of luggage transport, maps, and an information guide on what to see en route.

(TREKKING)

THE GR 20 // CORSICA

One look at Corsica’s coastline, its time-forgotten villages, and its mountainous middle and you just might join the local separatist movement to boot French rule so you can keep the Mediterranean isle for yourself. Yes, politicos do get shot here, but the 26-year-old insurgence involves mainly nuisance attacks: wee-hour, low-power bombings that target government outposts—never tourism, the island’s bread and butter. The best spot for your tour of duty is the GR 20, a 125-mile Grande Randonnée (really big walk) that cuts a diagonal path from Calenzana, in the northwest, to Conca, in the southeast. This is one of the most stunning—and challenging—mountain hikes in Europe. It’s segmented into 15 stages of six to seven hours each, loaded with dense pine forests, moonscape plateaus, glacial lakes, and flowery valleys. The route is meticulously marked and well traveled, especially in July and August, but beware: By trail’s end, your total altitude gain will be nearly 35,000 feet, much of it over rocky and exposed terrain. There are bare-bones hostels and campgrounds at the end of each stage, but no provisions—and very little water—in between. For help planning your route, visit the tourism office of the Parc Naturel Régional de Corse (011-33-4-95-51-79-00, () in Ajaccio, the island’s capital. French travel agency Nouvelles Frontières () offers eight- or 15-day guided trips for $700-$1,250.

The Power to Move You

More self-propelled adventures

(CANOEING)

THE GAUJA RIVER // LATVIA

Sandwiched between Estonia and Lithuania on the Baltic coast, Latvia is a growing blip on the ecotourism radar. And for good reason: More than half the country, which is slightly larger than West Virginia, is unadulterated nature. Much of the terrain is languid and low-lying—sprawling pastures, wooded groves, marshlands crowded with cranes and peregrines—but things turn dramatic at the town of Sigulda, 31 miles northeast of Riga, Latvia’s vibrant capital. This is your gateway to 227,000-acre Gauya National Park, and particularly to the Gauja River, which cuts a choice 56-mile path through dolomite cliffs and sandstone ravines. Makars Tourist Agency in Sigulda (011-371-924-4948, ) arranges three-day self-guided canoe trips for $62 per boat, including transportation to and from the river, gear, and camping fees. The trip starts in the northern bounds of the park, at the village of Valmiera, and you float back to Sigulda along the Gauja’s broad, rapids-free waters. Certain sections practically boil with trout and salmon, and the banks are thick with beavers, otters, and the occasional lynx. You’ll stop at riverside campsites, some of which have hiking trails that meander into the park’s deep forests and valleys.

(CAVING)

THE TATRAS MOUNTAINS // POLAND

Straddling Poland and Slovakia, the Tatras Mountains are an irresistible draw for European tourists. They come for the alpine summits (the highest is Mount Rysy, 8,198 feet) and world-class skiing. But if you want to get off the beaten path, go under it—into one of the range’s stalactite-studded caves, the patient result of carbonic acid eating away at the mountains’ limestone base over the millennia. Try the handful of easy-access caverns open to the public on the Polish side, notably the Mrozna cave, a horizontal jut 1,676 feet long. A one-hour underground tour follows a high-ceilinged path amid startling stalactites and trickling streams. The tourist office at the gateway town of Zakopane (011-48-18-201-22-11, ) is central intelligence for cave information and tour outfits. Tatras Mountain Rescue Team (011-48-18-206-34-44) is your ticket to serious spelunking if you have a modicum of fitness and don’t mind a tight squeeze. In addition to conducting searches, these mountaineers lead trips into hard-to-access or otherwise off-limits areas, particularly the Wielka Sniezna cave, the biggest specimen in the Tatras at 2,670 feet deep and 11 miles long. Guide services cost $100-$200 per day, by reservation only.