There's only one real rule to remember when skiing down the face of an active volcano in Nicaragua: Don't fall.

nicaragua

Flippers away: Reef-bound off Little Corn Island, in the Caribbean east of mainland Nicaragua

Flippers away: Reef-bound off Little Corn Island, in the Caribbean east of mainland Nicaraguanicaragua

With a couple of feet of snow, it'd be four turns down the 40-degree slope near the summit of Volcán Cerro Negro, a 2,215-foot smoldering mound that last erupted in 1999. On lava rocks, well, that's another story. Outfitter Pierre Gedeon, who lured me here, has would-be schussers sign a release in case the volcano blows them into space, but I was more leery of sharp little black rocks standing in for powder.

I launched from the top, soon picking up speed, and that's when I violated the rule. Because rock resists in a way snow doesn't, the proper turning technique involves planting and jumping. Instead, I tried to slide, caught my edges, and skidded down the volcano on my arms and chest. When I stopped, my forearms resembled carpaccio. I didn't need to look at my chest; the dozen red matchstick points on my shirt told that story.

Once I started turning correctly, though, the run was a blast. Gedeon, 37, a Frenchman who grew up skiing at Chamonix and carved his first turns on Cerro Negro in August 2001, did the last stretch in a straight line, lying back on his tails. Halfway down, I paused to look around. I could see four active volcanoes of the Cordillera Los Maribios stretching to the north, whitecaps on the ocean 20 miles west, and intensely green countryside rolling south to the horizon. Central America's largest country—49,579 square miles—has heaping helpings of what its neighbors offer: Caribbean islands to rival those in Honduras, cloudforests and fauna to equal Costa Rica's, impressively preserved Spanish colonial cities to match the ones in Guatemala, and enough secret surf spots along its 230-mile Pacific coast to put Panama to shame. It has 19 active volcanoes and dozens more that sit dormant. All this in a nation that hasn't felt the commercial scythe of Cancún-style development.

When we reached Cerro Negro's base, six armed men on horseback appeared. Twenty years ago, during the contra war, when U.S.-backed forces were fighting the leftist Sandinistas for control of the country, this might have been worrisome. Even today, many Americans think of Nicaragua as a war-torn nation. But political and criminal violence is rare now, after more than a decade of peace and with a stable government in place. And if the tourist infrastructure remains thin, it just means that visitors spend more time getting to know real Nicaraguans—and the expats who have gravitated to a country where their dollar goes further than anyplace between Mexico and Colombia.

The riders, it turned out, were deer hunters. We joked that we wanted to trade our skis for a horse. They laughed in a way that indulgent parents might, as if to say, “Yes, gringos are crazy. Some are dangerously crazy. But most, like these two carrying skis around a smoking volcano, are just harmless lunatics.”

During my two-week ramble last November—from the Cordillera Los Maribios to adventure base camps in colonial Granada and León, from San Juan del Sur on the Pacific to Little Corn Island in the Caribbean—I found the best things to do in Nicaragua. And not all of them are crazy.

Cycling and Skiing Among the Volcanoes

nicaragua

A San Juan surfer

A San Juan surfernicaragua

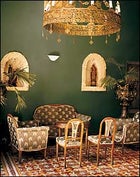

Hotel Colonial Grenada

Hotel Colonial Grenadanicaragua

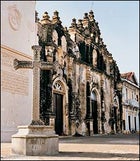

Grenada's La Merced Church

Grenada's La Merced ChurchCORDILLERA LOS MARIBIOS

Cycling and Skiing Among the Volcanoes

GEDEON TYPIFIES THE NEW CROP of outfitters that are setting up shop in Nicaragua. He migrated here from Costa Rica, where he had gone in 1996 hoping to carve a niche in ecotourism. “I was too late,” he says. “It was all developed.”

While visiting Nicaragua in late 1999, however, he found a fledgling tourism industry that had almost no sense of the country's adventure-sport potential. Gedeon relocated, launching conventional tours and spending his spare time scouting the Cordillera Los Maribios, a range that parallels the Pacific from the country's northwesternmost point down to the shores of Lago Xolotlan. After inaugurating Cerro Negro skiing, he worked out a mountain-bike route with help from a French expat volcanologist who has studied the Maribios for 30 years.

In 2002, Gedeon imported 30 French riders to participate in the first La Ruta des Volcáns, an eight-day jaunt that took them over six volcanoes on more than 100 miles of back roads and singletrack, with an optional ski run on Cerro Negro. They experienced everything from baking, barren lava fields to cool, tree-shrouded lanes that could have been plucked from the Tuscan countryside. At the end of each day, Gedeon took his weary mountain bikers to an overnight spot: a coffee plantation, a private beach, the capital city of Managua, or the colonial city of León, a former capital moved to its present site (20 miles west of Cerro Negro) in 1610 after the original was wiped out by a volcano.

After pedaling, skiing, or hiking on a day outing with Gedeon's Nicaragua ���ϳԹ���s—or replicating the whole La Ruta des Volcáns—the best way to rest tired muscles (and skinned elbows) is to take an outside table at El Sesteo, across from León's magnificent cathedral, constructed in 1747 and the largest in Central America. Order a Nica highball: a shot of 12-year-old Flor de Cana rum, a splash each of cola and soda water, and a squeeze of lime.

Gedeon and I ended our ski day there, and I asked him if a multi-day hike along the Ruta would be possible. He thought for a moment. “The problem is water, of course, but that could be cached. Yes, of course! It would be fantastic. That's the great thing about Nicaragua right now. It's all possible. You just have to imagine it.”

SEASON: July to August, November to April.

OUTFITTER: Managua-based Nicaragua ���ϳԹ���s (011-505-276-1125, ) leads custom mountain-biking, hiking, or skiing day trips. The eight-day La Ruta des Volcáns costs about $900, including lodging, food, and transportation. Gedeon supplies skis and boots for Cerro Negro; cyclists should bring their own supplies, including tools and tubes.

WHERE TO STAY: Hotel El Convento in León (doubles, $87, including breakfast; 011-505-311-7053, ) is a beautifully restored 300-year-old convent with gardens, colonial antiques, and monastic rooms.

WHERE TO EAT: León's best eatery is Taquezal, across from the theater, serving typical Nica dishes such as the strange-sounding but delicious cabbage-and-pork salad.

��

Wet ���ϳԹ���s with a Colonial Twist

nicaragua

A canopy tour outside the city

A canopy tour outside the citynicaragua

Colonial pleasures: Hotel Colonial Grenada's pool, the city's sweetest

Colonial pleasures: Hotel Colonial Grenada's pool, the city's sweetestGRANADA

Wet ���ϳԹ���s with a Colonial Twist

LED BY ANDY SNINSKY, a 55-year-old former California whitewater guide who works for the outfitter Mombotour, I kayaked past jungle through narrow channels in the Isletas de Granada, dozens of isles that range in size from a half-submerged boulder to an acre-plus. According to popular theory, rocks from the cone of Volcán Mombacho, which blew in the 1300s, formed the chain in Lago Cocibolca, also known as Lago Nicaragua. Sninsky shared this theory along with an impressive knowledge of birds (in two hours he spotted 40 species) and Granada nightclubs. He also freely dispensed good gossip about the ricos (rich people) who own some of the islands. That's what I call guiding.

Granada is among the oldest continuously inhabited colonial cities in the Western Hemisphere, founded in 1523. Another former capital of Nicaragua (Managua now claims that designation), Granada is the nexus for adventure tourism in much the same way Cuzco is in Peru. Within an hour of this southwestern city, you can kayak or fish for giant rainbow bass on Cocibolca, Central America's largest lake; take a canopy tour in the cloudforest of Volcán Mombacho; or hike the Puma Trail around Mombacho or the rim of the frighteningly active Volcán Masaya.

The best part of these pursuits is knowing that each night you'll return to a vibrant, architecturally rich city. You'll find a perfect perch overlooking Granada's plaza, such as the veranda of the Hotel Alhambra, and watch the easy rhythm of a city whose heart hasn't changed much in 400 years.

SEASON: Year-round, though April and May are brutally hot.

OUTFITTER: Granada-based Mombotour (011-505-552-4548, mombotur@ibw.com.ni) leads day trips of kayaking, Puma Trail hiking, the canopy course, or horseback riding ($15–$35). Bring a waterproof jacket in the rainy season, June to November.

WHERE TO STAY: Gigantic rooms surround a beautiful courtyard at Posada Don Alfredo ($27 per person, $6–$8 for breakfast; 011-505-552-4455, alfredpaulbaganz@hotmail.com). The breakfast is the biggest and best I've ever had—after six courses, owner Don Alfredo asks if you're ready for pancakes. Next to the plaza is the gracious Hotel Colonial Granada (doubles, $65; 011-505-552-7581, ), a two-story Euro-colonial favorite whose secluded pool is the city's best.

WHERE TO EAT: El Zaquan, behind the cathedral, is the place to go, with excellent grilled meat and fish starting at $6 a plate. Ask for guaote, the rainbow bass.

Surfing Capital of Nicaragua

nicaragua

Granada's Central Park

Granada's Central Parknicaragua

Isleta de de Granada

Isleta de de GranadaSAN JUAN DEL SUR

Surfing Capital of Nicaragua

IT HAD BEEN A REALLY TOUGH DAY. Dale Dagger, an ex–Maui soul surfer who has been scoping out Central American breaks since 1972, was piloting his 25-foot canopied lancha, the Veronica, north from the southwestern village of San Juan del Sur along the Pacific coast. During ten years in San Juan, Dagger has scouted and named nine excellent breaks within 90 minutes of the village by boat. Unfortunately, this particular morning, he was uttering words that reduce a grown surfer to tears. “It's strange,” he said. “It was great a couple days ago.”

So November isn't prime time for surf. As Dagger pointed out such favorite spots as Cowadunga (named after the sizable gifts cattle leave on the beach), with three separate peaks and rights and lefts that are consistently head-high, I was feeling like a chained-up mutt at a T-bone packing plant. It got worse when we cruised past his 32-foot surfing flagship, Masayita, which had dropped off eight surfers from New Hampshire at a place he calls Beach Break. Not to crowd them, we anchored a couple hundred yards south and dove in to bodysurf their leftovers.

Afterward, we headed a mile south to Dagger's favorite village, Gigante, a collection of palapas and concrete. At La Gaviota, one of two restaurants, the owner brought us each a pound of garlicky lobster tails, as well as rice, beans, salad, and beer. We gorged.

“Surfing in Nicaragua is all about access,” Dagger said between tails. “There isn't any. The beaches are public, but the land in back of them is all private, so it's extremely difficult to get to the best breaks. That's why going by boat is the answer—and if one place isn't going off, you can move on to the next.”

Dagger makes a practice of keeping spots secret and uses his own monikers: Cowadunga, the Left, the Reef Break, the Other Reef Break. “I think the majority of surfers would prefer not having places named,” he said as we finished, while Blanca, our hostess, prepared two large cots for siesta. “Because they want to discover a place before the hordes get there. And the hordes haven't reached Nicaragua. Yet.”

Our siesta ended when Blanca blasted the volume of her telenovela. We waddled out to the water and did our best to bodysurf off lunch. At sunset, we caught up with the New Englanders, sprawled on the deck of the Masayita, almost too trashed from seven hours of surfing to lift a beer. Almost.

SEASON: March to October (when the southern swells hit)

OUTFITTER: An eight-day tour aboard Dagger's Masayita, with hotel lodging, airport transfers, and breakfast, lunch, and beer daily, costs $960 per person. Dagger (011-505-458-2429, ddagger@ibw.com.ni) rents boards; bring your own stick and wax.

WHERE TO STAY: Most surfers stay three blocks from the ocean in San Juan at the 17-room Hotel Villa Isabella (singles or doubles, $65 per night; suites, $75, with breakfast; 011-505-458-2568, villaisabella@aol.com). A pool was set to open in March.

WHERE TO EAT: Piedras y Olas in San Juan would be three-star dining anywhere; go at lunch and swim in the café-side pool. In Gigante, La Gaviota—a.k.a. the Lobster Lounge—sells a one-pound lobster tail with two beers and a siesta for $6.

Diving the Old Caribbean

nicaragua

A kayak tour

A kayak tournicaragua

The countryside north of San Juan

The countryside north of San JuanLITTLE CORN ISLAND

Diving the Old Caribbean

WHEN I NOTICED THE STRANGE brown shapes rolling a few feet offshore, I was sitting outside the Dive Little Corn shop talking with its managers, Waz Meredith and Elle Schneider, about the scuba diving around this 1.2-square-mile jewel 50 miles due east of the mainland. Little Corn is the Caribbean of a half-century ago. Everything is simple, distilled so you can look around and know you're in paradise. Meredith, a big, friendly Aussie, described how he and Schneider, his soft-spoken Israeli wife, had scouted the reefs for the best dive spots when they arrived two years earlier—she drove the boat and towed him on a glorified piece of wood. “It works just like an airplane; lean on the edge to angle down into the water and—zoom!—down you go.”

With its incredible underwater wildlife, remote Little Corn Island (a 30-minute panga ride from Big Corn Island) has emerged as a diving hot spot. Undamaged reefs harbor giant groupers, eagle rays, nurse sharks, and sea turtles. The diving is relatively shallow, around 30 feet, so divers have a lot of bottom time to explore the reef passageways and get their minds blown by the sheer volume of fish.

Personally, the only fish I wanted to see were the ones hooked to the business end of my fly rod. Another Aussie had described huge schools of bonefish that come from the north and end up in a little lagoon below some cliffs on the windward side of the island. He said they circled around in such a mass that when you dropped your fly in, you weren't sure whether you'd hooked one or the crush of fish was simply taking it away. I was contemplating this when I saw the boil.

“Oh, that,” said Waz. “They're tarpon. Right in front of the hotel, just like clockwork.”

Excusing myself none too gracefully, I ran to grab my rod. I got a few clumsy casts in before they disappeared. Still, it was a hell of an exciting 15 minutes.

I retired to the balcony of a hotel nearby to see whether the tarpon would return. An island man—whose ancestry, like that of a good number of the 900 or so other Little Corn Islanders, is English and African by way of the Caymans—approached and asked if he and his uncle could help me net some tarpon the next day.

“But I warn you,” he said, “tarpon are no good to eat.”

“I wasn't planning on eating one. I was going to catch and release one.”

“Then why you want to bother that fish for?” he asked, genuinely puzzled as to why anyone would waste their energy and the fish's time in such a pointless pursuit.

It was a good question. An indication I was in paradise—or damn close to it.

SEASON: January to May, September and October

OUTFITTER: Dive Little Corn () offers two dives for $78, a four-day PADI course for $315, and a seven-day Dive Master course for $675, all with gear. Bring your own rod and tackle, plus flies for tarpon, bonefish, and yellowtail.

WHERE TO STAY: The 11 guest rooms at Casa Iguana () are situated in breezy pastel casitas and priced from $25 per night, for an efficiency with shared bath, to $85, for the secluded Grand Casita. Casa Iguana has its own beach and an outdoor rainwater shower.

WHERE TO EAT: It takes 30 minutes to hike from town to Farm Peace and Love (farmpeacelove@hotmail.com), Paola Carminiani's home and restaurant (take a guide), but her three-course meal of fresh seafood pastas, thin-crust pizza, and dessert ($10) is worth the schlepp. A reservation is required.