I CALLED THEM SLIME NUGGETS, though I should have been more gracious, as they were one of the few things keeping me alive. I discovered the mollusks on my second day stranded on a desert island called Pargo, in Panama's Gulf of Chiriquí. I carried little more than a knife, a dive mask, and the clothes on my back and hadn't yet taken down a mastodon, so I embraced the variety they offered my coconut-and-termite diet.

Commonly known as limpets, the slime nuggets lived in the intertidal zone. They'd be better cooked, certainly, but I'd been unable to make fire and was lucky to find something I could eat raw. They tasted like soft rubber slathered in gelatin it took 60 solid seconds to chew each quarter-size chunk of flesh into an ingestible pulp but their consistency allowed me to savor the fact that I wouldn't die of starvation anytime soon. My brain successfully spun each disgusting bite into a victory until my fifth day on Pargo, when my body finally revolted.

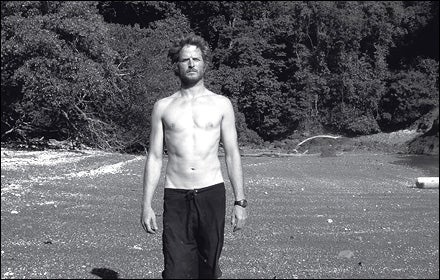

��

It started with the scum sack, the thin mucous membrane holding in the slime nugget's viscera (also known as guts and shit). Before I could eat a slime nugget, I had to pry it out of its shell and cut out the scum sack. I had grown accustomed to the rainbow of repugnance that erupted, but after three days of choking down the mollusks I discovered that, in all probability, I'd been eating something else, too. With a handful of nuggets in my mouth, and another handful waiting to be cleaned, I watched a phalanx of small, brown flatworms emerge from one of the scum sacks. They had a Hydra-like response to being cut in half: Two heads are better than one. I puked.

My entire caloric intake for the day lay partially digested at my feet, and there was just one way to replace it. I threw the worm-infested mollusk away, sat down defeated, and began cleaning another round.

Before I arrived on Pargo, I'd joked that I, a novice in wilderness survival, was stranding myself because I wanted to update the adage “Will work for food” to “Will starve for work.” As fresh slime mixed with the puke's acidic residue, I remembered the joke. “Who's laughing now?” I cursed.

Still, I was confident. One friend predicted I'd last only four days on the island, but I figured on somewhere between 12 and a month. Forty had a nice biblical ring to it. I'd be Tarzan in no time. How hard could it be?

IT HAD SEEMED like a good idea, on a full stomach: a true test of survival, a concept that has captivated our collective psyche from the Israelites' passage through the desert all the way up to the 14th season of Survivor. Most everyone has wondered how they would do in such circumstances. I intended to find out by dropping myself on a desert island.

The key was finding the perfect place. The island needed to be uninhabited, but close to help. It had to have fresh water, a food source, and a tropical climate, because I didn't fancy reliving the Shackleton expedition. After two weeks of searching, my focus narrowed to Islas Secas, a 16-island archipelago 12 miles off Panama's Pacific coast.

The Islas Secas resort sits on the only inhabited part of the chain, and Michael Klein, the hotel's owner, told me about its desert neighbor, Isla Pargo, two miles away: a 480-acre island with fresh water, coconuts, and an abundance of sea life. There are no mammals, but plenty of birds and iguanas, if, he added, I could catch them. Help was about ten minutes away by speedboat, and there was even an airstrip near the resort in case of an emergency.

Since the idea was to survive, not to die, there were some ground rules. First, I wanted to bring along as little as possible. At the suggestion of every survival expert I spoke with, I brought a knife, in this case a foot-long Ka-Bar Heavy Bowie. For entertainment purposes I brought a dive mask, with the added bonus that it might help me catch dinner. A basic first aid kit was necessary to clean wounds. Media equipment notebooks, pens, cameras (both still and video), and a Brunton solar panel to power them was needed to record this story. In case of an emergency, my Big Red Button was an Iridium satellite phone. Every three days I'd call my editor, Mary Turner, when I knew she wouldn't be in the office, and leave a “still alive” voice mail. If she didn't hear from me, she'd call the Islas Secas resort and the staff would search for my body. As a backup I had an ACR personal locator beacon to alert the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration about my location. But what I really needed was survival skills.

I am not a survival expert. The last time I killed anything was with my truck. When asked to assess my skills, Bob Berman, my mother's steady of 12 years, suggested that I'd do “better at local bars than alone on an island.” I grew up in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury district, a city kid to the sneakers. As a healthy, adventurous 28-year-old I spend a lot of time outdoors, mostly in the water surfing, kayaking, kiteboarding and I'm a Scuba dive master. But these are finite activities bookended by coffee in the morning and a frosty Boddingtons at night.

“It's tough,” warned Les Stroud, creator and star of the Science Channel's Survivorman, when I asked for advice. Stroud has been practicing survival skills for 20 years, and still calls a week in the wild a long haul. “It's really easy to say, 'I'm going to be able to get some fish, I'm going to get some iguanas,'” he told me. “Then you go put it into practice and it's a whole other ball game.”

Fortunately, I had signed up for a crash survival course with Stroud's former teacher, John “Prairie Wolf” McPherson. Prairie Wolf and his wife, Geri, authors of the Naked into the Wilderness books, teach survival skills to, among others, Green Berets. They live off the grid in a three-story log cabin they built themselves, in eastern Kansas. Prairie Wolf, 62, earned a Purple Heart in Vietnam and makes Rambo look soft. Geri, a 64-year-old great-grandmother, specializes in tanning animal skins in their own brain juice.

Green Berets typically spend two weeks mastering skills with Prairie Wolf and Geri, but I had to cram everything into five days. They showed me how to make traps, fire, shelter, and rope, but first they had to teach me how to whittle. None of the materials we used would be available in Panama, Prairie Wolf explained, but the tropics, with all its biodiversity, should have plenty of good wood.

On the first afternoon, while Prairie Wolf ran errands and Geri skinned a deer, I made a fire with a bow drill. I used materials Prairie Wolf had made from softwood (ideal for fire making), with tinder he had helped me collect, but that hardly mattered. When he returned to find me standing victoriously in front of my roaring inferno, I told him to call me the Human Torch.

“Good job,” he said. “But don't get too cocky. Fire is always most difficult when it's most important.”

It took me two more days to spark another flame. Geri urged me not to get discouraged and explained that it had taken her months to make fire routinely. I didn't have that luxury. I made fire a few more times before leaving, but I couldn't shake the feeling that spending five days in Kansas a month before my departure was a lot like cracking a few law books the night before the bar exam. When I left, Prairie Wolf wished me luck. I could tell he meant it.

CAPTAIN MANUEL GARCIA sped the boat around the point, dropped anchor in the W-shaped bay, and cut the engine. Two beaches lay before us, divided by a rocky point. I named the eastern one, which would become my home, Two-Liter Beach, for the bounty of flotsam mainly plastic bottles that had washed up. hese were abrasive beaches, covered in small rocks and broken coral, not the soft, relaxing kinds usually paired with paradise.

The interior was no friendlier. Nispero trees, some centuries-old and over 100 feet tall, crowned the landscape, and below them ran a tangle of vines, branches, and other hardwood. Deadfall covered the ground, and a thin stand of palms buffered the shoreline. “The big problem on Isla Pargo is the chitras,” Garcia said, referring to the island's sand flies. He and other locals had warned me to bring bug spray, counsel I had flouted. “All the time it's chitras, chitras,” Garcia said. As he spoke I realized this was the last conversation I'd be having for a long time. I jumped off the boat and waded to shore. Garcia fired up the engine and disappeared.

Then I cut down a tree.

This served no immediate utilitarian purpose; it just felt good and I wanted to begin with a triumph, no matter how small and meaningless. It was 9:30 in the morning, and for the first time in my life I had to consider where I'd find my next sip of water.

The day before, while scouting Pargo with Garcia, I'd discovered there was no running water a surprise, given that he'd seen running water two weeks earlier. The Panamanian summer was quickly sucking the island dry, leaving just a large swamp on the north side and two small and stagnant pools on the south. The water had to be coming from somewhere, so I'd shoveled a two-foot-deep well. Brown water had seeped in. It didn't look like anything I'd want to drink, but it came straight from the ground, so I figured it was pure. I'd filled the hole in before I left and reexcavated it with a digging stick during my first hours on the island.

The rest of the day was spent working on fire. Aside from fuel, there are five elements necessary for a bow-drill fire: bow, string, drill, fireboard, and bearing block. I found my bow immediately, and it was perfect: dead but not brittle, and two and a half feet of the most beautiful arc this side of the Roman aqueducts. My shoelace took care of the string. Two branches served as drill and fireboard. For the bearing block, which holds the drill in place, I used a broken coconut shell. The bowstring wraps around the drill with the whittled point pressed into the fireboard. As the drill spins, the friction creates smoke and, theoretically, an ember. But six hours of fruitless toil later all I had was six blisters.

It would be dark soon, so I gathered logs of bamboo drift to make a raised bed frame, and then covered it with palm fronds. I had worked hard all day and felt good. A twinge of loneliness hit, and I thought of my last human contact. Garcia. Shit. The chitras.

In the sand fly, God has created a creature that doesn't sleep. During the day I couldn't sit still for 30 seconds without being swarmed. This made meals challenging, and in an exasperating piece of consumptive symmetry, they bit my face while I chewed. But the nights were truly horrific. The sand flies flew up my nose and into my mouth; they launched repeated expeditions down my ear canal.

On day three, when I left my first scheduled message for Mary, I sheepishly asked her to have my resort support team drop some bug spray on the other side of the island for me to pick up. Later, my pregnant sister would call me a sissy. But she wasn't there, man. She wasn't there.

This wasn't the first time the island had tormented me. Though Panama was in its four-month dry season, the night before I'd awakened to the deceptively pleasant pitter-patter of rain. Stumbling through the black jungle in search of cover, soon I could no longer see my bed. I was lost within 200 feet of my wet nest. Jogging along the beach to keep warm, all I could do was laugh and wait for dawn.

I decided to devote a day to building a lean-to, chopping down small trees for the frame and covering the slanted roof with a heap of coconut fronds. It wouldn't have been out of place in a garbage dump. I called her Monticello. With water, food, and shelter, I needed just one more thing: fire.

MOST DAYS BEGAN with exercise, though not of the conventional sort. I'd roll off the logs by 7 A.M. and, just as I do back home, start my day with fruit in this case, coconut. Hacking through the tough fibrous shell of a brown coconut takes considerable effort, but this I anticipated. The curveball was the meat; I didn't realize how stubborn the flesh actually is. Only once did I eat an entire coconut in a sitting, and it took me 40 minutes of committed mastication.

Coconuts were followed by a course of live termites, or, if the tide was low, 20 or so slime nuggets. Sometimes both. Every few days I filled a stockpile of plastic water bottles from the well and drank copiously, both to stay hydrated and to trick my stomach into thinking it was full. The rest of the day was dedicated to projects. Somewhere in there, I filmed and took pictures, and around 3:30 P.M. came the highlight of my day: an hourlong snorkel with beautiful and delicious-looking reef fish. Then I wrote in my notebook, and before nightfall I took a shower with a flotsam bucket in a grimy ankle-deep pool downstream of the well. Darkness fell at 7 P.M. and lasted 11 and a half hours, then the merry-go-round started anew at sunrise. I was lucky if I stole six hours of sleep.

��

On day six, somewhere between termites and snorkeling, some local fishermen dropped anchor in the bay. The Secas is an isolated archipelago, but not a forgotten one, and fishermen sometimes stop there for food and water. I hid behind a tree, undetected, until one of them headed straight for my camp.

I forced myself out of the bush and said hello. It had been nearly a week since I had seen anyone, and my initial disappointment turned to elation. The fisherman was salty, scruffy, and had the friendliest, most beautiful face I'd ever seen. He explained that they were searching for land crabs for dinner. They're delicious when cooked not so much raw. I know because I tried. In halting Spanish, I explained why I was there.

“Whoa,” the captain said. “How long have you been here?”

“Six days,” I told him. The other four fishermen gathered around. They were ten days into a two-week trip.

“And how long will you stay?” another asked.

“I don't know,” I replied. “A few weeks. A month.”

They looked at each other. “You're crazy,” the captain said.

“But you're spending two weeks on your boat, away from home,” I countered.

“Yes,” said the captain, “but we have each other. And fish!” I laughed enviously. With that they left, but not before the youngest one he looked like a teenager brought me two coconuts. I could have gotten them myself, but still it was a nice gesture, a random act of kindness. I had almost forgotten such things.

TWO MORNINGS LATER, a raptor perched on the branch of a large dead tree, near the breakfast log where I'd chew my daily cud of coconut. He seemed unconcerned when I crept within ten feet of him; he stood there for 30 minutes staring at the ocean, trying to figure out what the hell to do with his day. We had a lot in common.

I wasn't sure what kind of bird of prey he was, but he was handsome, well-groomed, and slightly aloof, so I named him after the guy I thought starred in the 1980s TV show Falcon Crest: Pierce Brosnan. (Only later would I realize it was Lorenzo Lamas and the bird was a hawk.)

Pierce went fishing soon after the christening, and I followed suit. There was a stocked tide pool just up the point that looked like a great sushi bar. It was 8:30 A.M. and I was hungry, so I made a fish trap. I hadn't eaten in 20 hours. I cut the top off a two-liter plastic bottle, then jury-rigged it with some branches inside. With any luck, fish would swim into the bottle for the slime-nugget guts laid as bait, but wouldn't be able to swim back out like a lobster trap.

After setting the trap, I scarfed down 18 nuggets. I was weak, tired, and lonely. In eight days, I'd made no progress with fire. Part of the problem (besides the lack of a lighter) was that I was sitting in the middle of a hardwood forest, and I needed softwood to make fire. I spent all my nights in darkness and ate every meal raw. That wasn't my only failure. I spent three days tying a fishing net that wouldn't have caught a basketball. It took me a day and a half to carve bone spearpoints, which were too short. I launched a sophisticated operation called Bait and Bash, lining a shallow pool with slime nuggets to attract fish that, in theory, I would then pound with a rock. I missed every time. I was failing, critically, and sometimes hourly, and I had no one to turn to.

Exhausted, I cracked a coconut and lay under a tree that seeped caustic sap. “I am the world's most pathetic human,” I muttered. “I can't make fire, I don't have any fish. I should have gone into real estate.” It degenerated. “Tomorrow will be harder than today, and today is the hardest it has ever been.” It was only 11:30 in the morning.

Stroud had advised me that staying busy was the best way to stave off depression. There's just one problem with that: Staying busy hurt. Filling water bottles exhausted me. Opening coconuts left me drained.

And then, as quickly as it hit, the despair retreated, driven away by stubborn pragmatism. I checked my fish trap. No sushi tonight. I untangled part of a fishing-line heap that had washed up on shore and began tying a net. I went for a long swim, saw a three-foot moray eel, and navigated a tight swim-through. Back on shore I ate 15 more nuggets, got cleaned up, and began clearing a path from the beach to Monticello. As the sun set, I thought, Tomorrow may be harder than today, but today wasn't too bad.

IN ROBINSON CRUSOE, Daniel Defoe's title character describes himself as a “prisoner lock'd up … in an uninhabited wilderness.” But with time Crusoe's outlook changes and he perceives himself not as inmate of his desert island, but as king. “I was lord of the whole manor …” he later proclaims. “I had no competitor, none to dispute sovereignty or command with me.”

I too would be king, and day 12 would be my coronation. So at 9 A.M., with the tide dropping in my favor, I struck out to survey the kingdom and claim it as my own.

Though Pargo is smaller than one square mile, it's difficult to explore; dense jungle cloaks the interior, and moving around the jagged volcanic-rock coastline often requires steep climbs or challenging swims. After an hour or so, I came to a large bay, several football fields wide. At the far end stood two rock spires, each roughly 100 feet tall, with a prominent saddle between. It was a steep climb to the saddle, 60 feet up crumbling rock and loose dirt, above a rock platform that would soon be covered by water. Plants with long ribbons of leaves sprouting from the ground like a Muppet wig offered my only handholds. I put my foot on one and it gave way and plummeted to the rocky shore. To catch my fall I grabbed another plant, only to find it was the sea urchin's flora relative.

For the first time in nearly two weeks, I said to myself, “You know, Thayer, you probably shouldn't be doing this.” While descending the other side, every move was difficult and dangerous. But 30 minutes later, my reward appeared.

It was a beautiful empty beach. I rolled around in the hot, powder-white sand and, even though I was exhausted from all the hiking, strolled along the waterline how often does a person have his own beach?

On my way back to camp, I came to a small clearing containing ten tall stalks of sugarcane. Out came my knife, and down went a stalk. I peeled back the husk and chomped into sweet, juicy, 100 percent unadulterated sugar. My taste buds, hiding for almost two weeks, exploded in celebration. I sat in the clearing the Sugar Factory, I called it for an hour, a little pink gorilla chomping on stalks of sugarcane, high on sucrose and the most concentrated shot of happiness I've ever had.

After chopping down a large piece of cane, I made for camp. At a viewpoint overlooking turquoise waters, I held the three-foot stalk of sugar like a scepter and proclaimed, “My name is THAYER, and ye shall know me as KING!”

“I'M DONE SURVIVING,” I wrote in my journal. “Today I begin to live.” After 15 days of foraging for food and drinking murky water, I had plateaued. I wasn't dying or going crazy, but I wasn't thriving, either.

There was one skill I was convinced would haul me up the evolutionary ladder from surviving to living: basket weaving. I spent more than a day weaving hacked-up saplings and vines into a basket and lid, both cone-shaped. It worked perfectly. I slung it over my shoulder to collect slime nuggets, and it held twice as many as the empty coconut shell I had been using. It didn't look half bad, either. Making that first basket was my proudest moment on the island.

A basket, you see, has multiple uses. Flip the lid upside down, insert it into the bottom, and the whole thing becomes a fish trap: They could swim in but might not swim out. I filled the basket with rocks and slime nuggets and stuffed it into a crevice where fish gathered. I tied one end of the fishing line to the basket and the other to an empty bleach bottle that floated like a buoy. I could leave it out all night secured like this and the next morning it was sure to hold something. Just one small success would change everything. On the afternoon of day 17, I set my first trap and headed into the jungle for a celebratory run to the Sugar Factory.

Slogging through a creekbed covered in thigh-deep leaf litter, I saw, 18 inches away, an iguana. I had seen a million iguanas on this island and hadn't gotten within 20 feet, and here was one sitting a foot and a half away. It didn't matter that I didn't have fire hell, if I caught an iguana, I'd piss fire. Or I'd dry the meat and make iguana jerky. I'd swat flies away all night it's not like I was sleeping anyway.

I picked a large branch off the ground, summoned all my savagery, and bashed the lizard on the neck a direct hit. The branch snapped in my hand; the iguana didn't move. Just as the words “Maybe it's dead” raced through my mind, the iguana tore into the bush. It had practically crawled onto my dinner plate, and still I blew it.

After a quick stop at the Sugar Factory, I returned to camp. The basket trap was gone, swept away by the outgoing tide. “If ever there was a sign …” I told myself. I spent the day's last minutes getting hopped up on sugar, then stayed awake half the night wondering what iguana meat tastes like.

By day 19, I came to a few realizations: If survival depended on making fire and catching fish, I'd be in trouble. If survival depended on eating slime nuggets and drinking water from a muddy hole, I could do it indefinitely. I had been delusional to think that I would master primitive survival in a few weeks, after we humans spent millions of years learning these skills and then millennia forgetting them. Though I'd lost 14 pounds, I'd gained one ton of humility. Pierce Brosnan flew over and I shouted, “I want a turkey sandwich!” Entirely disinterested, he flew back to his nest.

The next morning, I did, too.

I HIT CIVILIZATION like a swarm of locusts. On the pickup boat, I inhaled the fastest and most memorable meal of my life an egg-and-sausage sandwich, two moist and delicious banana-nut muffins, a fruit medley, and a Coke. At the Islas Secas hotel, I vacuumed up a truckload of chicken veggie pasta, chugged a beer, and waited for my walnut-size stomach to protest.

When I saw Deborah Bunting, a matronly former schoolteacher who manages the resort with her husband, Guy, and whom I barely knew, I threw my arms around her as if she were my mother. She patted my back awkwardly, then tried to extricate herself. “Wait, wait,” I said, and squeezed tighter.

Later that day, I traveled to the mountain town of Boquete, about as far from the ocean as possible in Panama, to stay with my friends Dee and Rich Lipner. On the second day I plowed through six meals and three desserts, unconcerned that each gluttonous bite would have a consequence. I squirmed in pain throughout the night and discovered why when I weighed myself the next afternoon: I had gained six pounds in three days.

��

Some things quickly returned to normal: Traffic resumed its place as an annoyance rather than a novelty, and I didn't feel the need to make eye contact with every stranger I passed. Other things won't ever be the same. Spending three weeks getting bitch-slapped by nature has an odd way of humbling a person. What did it matter that I could craft a sentence if I couldn't produce fire? Never again will I ask for a light with the same nonchalance.

I called Les Stroud when I returned and told him about my experience. He didn't sound surprised. “The reality of making a tool or a hunting or fishing implement, and then matching that with an efficacy it's a big chasm,” he said. “They hardly ever work.”

“I didn't even make a spark,” I said.

“That's the toughest thing,” he explained. “I'm sure that some of us could have done better than you, because of our skills, but not that much better. Survival is grueling and ugly. Twenty days is a long time. I wouldn't want to do it.”

A few days after leaving Pargo, I found myself at a restaurant with the Lipners talking through my successes and failures. I ordered a piña colada at the waitress's suggestion. I smiled and said, “It's nice to have choices like these.” When the drinks arrived, I sipped the piña colada and got my first hit of coconut since leaving Pargo. I didn't even taste the alcohol. Just the island. I slid the drink across the table to Dee.

“You can have it,” I told her.