An Impossible Place To Be

Panama's mythic Darién Gap—a 10,000-square-mile swath of jungle on the border of Central and South America—has swallowed explorers for centuries. Today, guerrillas, drug smugglers, poachers, and jaguars rule this vast no-man's-land. Our explorer spent six weeks trying to penetrate Darién's heart of darkness, but the Gap still fiercely protects its secrets.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

In Yaviza, a town of contrabandistas, barefoot prostitutes, and drunken men fighting in the streets with machetes and broken bottles, I'm spotted by two Panamanian policemen and ordered to the cuartel (barracks). It's noon on a Saturday, and I've just arrived in this forlorn 3,200-person trading outpost in the Darién Gap.

“Pasaporte,” demands the sour-faced officer at the cuartel. Taking it from my hands, he asks, “Americano?” Then he writes my name in his registry of visitors. “Have a seat,” he says. “The comandante is coming.”

Yaviza, 30 miles from the Colombian border, is famous for lawlessness—it's a magnet for fugitives, poachers, and bootleggers. Many of the restaurants openly sell sea turtle eggs (fried or scrambled), a prized but illegal delicacy. Put out the word that you want a blue-and-yellow macaw as a pet and eventually there will be a knock on your hotel-room door. Yaviza's whorehouses have long been favored by anti-government guerrillas from Colombia—indeed, a high-ranking rebel is said to maintain a pied-à-terre here.

So there's irony in being grabbed by the police. But the humor vanishes when the balding comandante, dressed in fatigues, shows up and tells me the whole area has been shut down.

“Shut down?” I ask. “Including Darién National Park?”

The comandante nods. “For security reasons,” he says.

The national park is what I have come to see. It's December 2003, and I've traveled 145 miles southeast from Panama City by a succession of rickety buses and farm vehicles. The 2,200-square-mile park, untamed and essentially roadless, sits like a lopsided U against the Colombian border. The rarely visited area, which makes for an impassible divide between North and South America, is a mystery zone within an extraordinary, much larger wilderness—the 10,000-square-mile Darién Gap. Stretching from the sandy shores of the Caribbean south to the rocky cliffs of the Pacific, the Gap begins just beyond the suburbs of Panama City and sprawls east, thickening as it goes, until it has erased all roads, all telephone lines, all signs of civilization, turning the landscape into one solid band of unruly vegetation filled with jaguars, deadly bushmasters, and other exotic wildlife.

The mere existence of such a throwback in the modern world suggests an inviolate timelessness. But as I learned in Panama City, the park is in trouble, jeopardized by its remoteness, the very quality that in the past has ensured its survival.

Indra Candanedo, a 38-year-old biologist in the Panama branch of the Nature Conservancy, introduced me to the possibility that the Gap might be eroding. As we sat in her office overlooking the capital's gleaming skyscrapers, she described a set of disturbing satellite images she had recently seen.

“It looks bad,” she said, noting that huge swaths of the park appear to have been deforested.

Candanedo couldn't be certain about this, because satellite imaging usually doesn't give a complete picture in places like rainforests, with their heavy precipitation and cloud cover. So why not check things out on the ground?

That option isn't so easy. Neighboring Colombia, just across a porous border, is one of the bloodiest countries in the world, making the Gap an intensely dangerous place. In the mid-1990s, following a spate of kidnappings and massacres related to the endless Colombian civil war, conservation programs and scientific research were drastically scaled back—at a time when the Gap was coming under increasing strain from landless farmers making new homesteads, slashing and burning to clear agricultural plots inside the park. Even Panama's own security forces withdrew, leaving large sections of the park unmonitored.

Candanedo, who had been the park's director in the mid-1990s, knew exactly how vulnerable it was, and she had enough information to be troubled. “You should see it for yourself,” she said. “If you can.”

The next day, upon returning to the cuartel in Yaviza, I find that the police have inexplicably changed their minds. I will be allowed to continue toward Darién National Park, provided I receive permission from the police in El Real, another tiny town that serves as park headquarters.

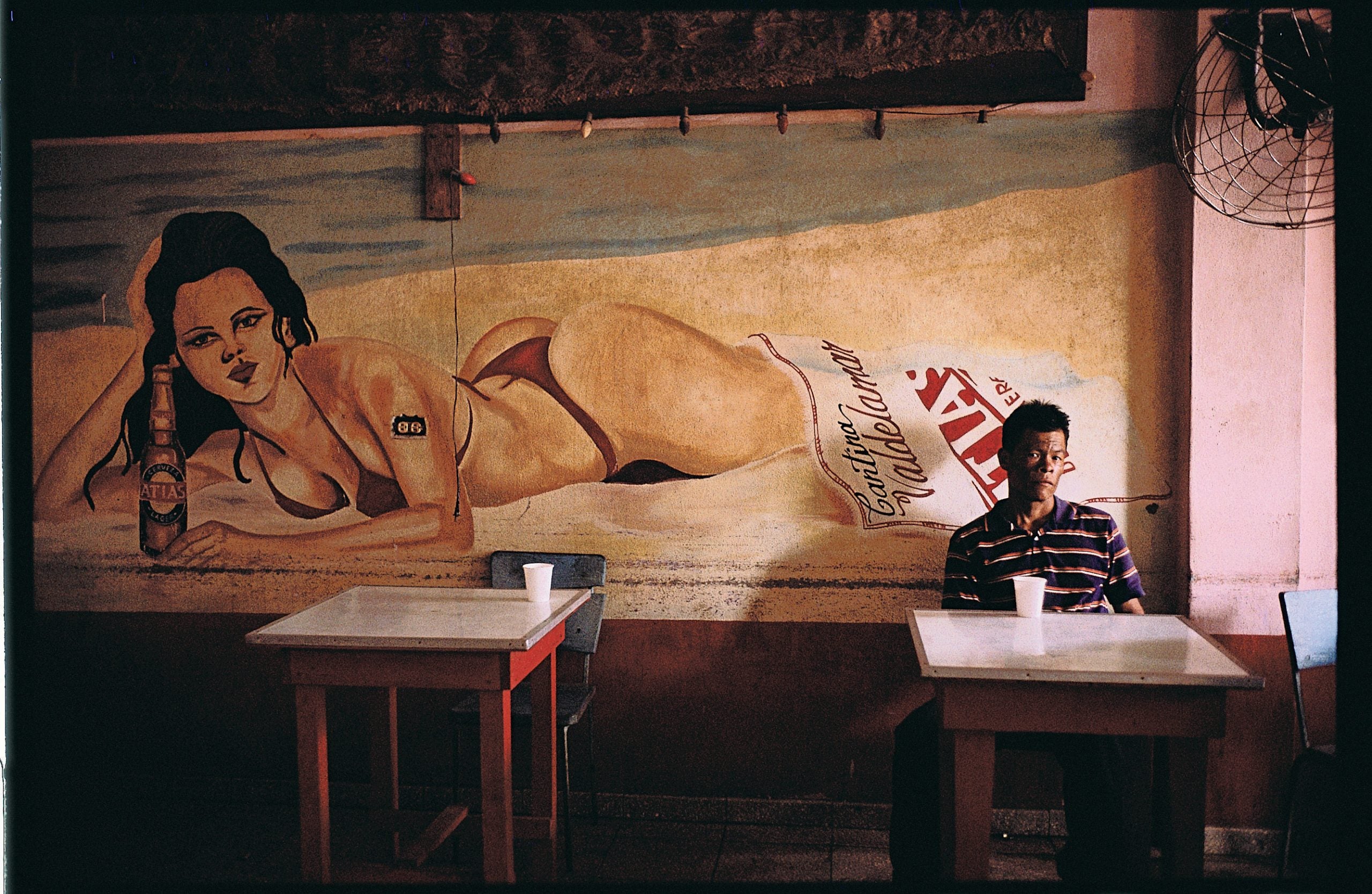

Leaving the cuartel, I walk to the Yaviza waterfront. In the shadow of La India, a raucous cantina adorned by a mural of a naked blonde, I make a deal with the owner of a dugout canoe and resume my journey, by river, into the heart of the Gap.

An “abyss and horror of mountains, rivers, and marshes,” in the words of one 16th-century traveler, the Darién Gap is Panama's Bermuda Triangle: a place where things seem to go wrong more often than everywhere else. As an old saying goes, the Spanish conquistadores defeated the Andes, the deserts, and the Amazon, but not the Gap, which foiled their advances.

The Gap is small compared with tropical wildernesses like the Amazon and the Congo. Yet it feels huge, with its slight population—roughly 100,000 people, half afro-Caribbean and half native Panamanian—mainly concentrated in isolated bush villages like Yaviza. In Panama and Colombia, it is known as El Tapón (“The Plug”), because it blocks the flow of human exploration. The Spaniards discovered it in 1502, founded their first mainland colony there, and then set the tone for centuries to come with a staggering atrocity: the murders, over an eight-year period starting in 1513, of tens of thousands of natives, many of them killed by vicious war dogs that attacked their villages.

By the late 18th century, the Spaniards, repulsed by the Gap's inhospitable environment, had left the region to rot in peace. Nourished by one of the wettest climates on earth—up to an inch of rain per day during the rainy season—Darién's jungle flourished unchecked, providing an ideal refuge for outlaws, pirates, runaway slaves, and fiercely territorial Kuna Indians. Over time the “myth of Darién” would arise from a series of spectacular tragedies, including the deaths, in 1699, of 2,000 Scottish colonists (from shipwreck, malaria, and starvation) and, in 1856, of seven explorers who became hopelessly lost on a U.S. Navy survey expedition. Canals were planned for the Gap, which is approximately 50 miles wide at its narrowest sea-to-sea point, but none were executed.

Today, having resisted five centuries of encroachment, the Gap may finally be running out of time. As environmentalists have stood by, helpless to get involved on the ground, a multitude of unseen enemies—poachers, poor farmers, refugees, small-scale timber companies—have been whittling away at its forests.

The question is, how did the situation suddenly get so precarious? Hoping to find out, and ignoring a U.S. State Department advisory emphatically discouraging travel to eastern Panama, I first visited the Gap in the summer of 2003, spent three weeks unsuccessfully trying to get inside Darién National Park, and returned twice in subsequent months. On each occasion I ran into the problem that has bedeviled outsiders from the start: access. Though not impenetrable, the Gap remains a formidable challenge to navigate. From Panama City there is only one road, the Pan-American Highway, which dead-ends in Yaviza. From there until Guapá, Colombia, some 90 miles away, there are nothing but mud tracks and footpaths.

The Gap is still a refuge for outlaws—only today, instead of pirates, there are the guerrillas and their ultra-rightist enemies, the United Self-Defense Forces, who are generally known as the paramilitaries. The guerrillas belong to the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC); they come to neighboring Panama not only for the nightlife in villages like Yaviza but to buy and stockpile weapons. (According to a recent report by the Rand Corporation, a nonpartisan California think tank, Panama has become “the single largest trans-shipment point” for the majority of small arms flowing into Colombia, “mostly across the densely forested Darién Gap.”) The paramilitaries, who are funded by Colombia's wealthiest landowners, come for the same reason, as well as to fight over a tremendously lucrative drug pipeline. The violent contest between these two groups constitutes the most urgent threat to the Gap today; the chaos they create prevents government and conservation watchdogs from doing their jobs.

Indirectly, their fight is also a threat to the United States. For decades the Gap has kept South American problems from spreading—not just illegal immigration but contraband and diseases that, while not exclusively South American, don't exist in the north.

“We let the jungle protect our border,” says Stanley Heckadon, 60, a Panamanian anthropologist and former head of INRENADE, the precursor to ANAM, the national government's top environmental authority. Since the 1989 U.S. invasion to topple General Manuel Noriega, Panama has been without an army, and until recently its police forces have had an unspoken policy of not confronting the Colombian militants.

Letting the Gap serve as a natural barrier “requires very little investment,” Heckadon adds. “And in the past, it has actually tended to work.”

A week before my trip to Yaviza, on my first foray into the park, I visited Jaqué, a village of a few thousand people where the guerrillas buy groceries and get their cavities filled. Jaqué lies 200 miles southeast of Panama City, just outside the national park, along a rocky section of Pacific coast marked by lengthy stretches of exquisite black cliffs. There are no roads nearby, and the government maps are covered with blank spots marked INSUFFICIENT DATA. As I flew in aboard the twice-weekly plane from the capital, I tried to keep track of our position, but all I saw was an endless span of green extending into the cloud-covered peaks of the local mountain range, Serranía de Jungurudó.

In the seat behind me was Julie Velásquez Runk, a 35-year-old graduate student from the Yale School of Forestry. A native of Detroit, Runk has spent much of the past seven years studying historical ecology in the Gap and living with the Wounaan, an indigenous tribe that dwells along its rivers. I'd asked her to accompany me so I could see the Gap through her eyes. Our plan was to find a guide with a boat, then ascend 20 miles up the Río Jaqué to the heart of the national park.

Our base was the Tropic Star Lodge, a strange outpost five miles west of Jaqué that was built in 1961 by Ray Smith, a Texas oil baron. The Tropic Star sits on secluded Piña Bay, circled by mountainous jungle. It's a Thunderball-style palace that offers prime access to what many consider the greatest sportfishing in the world. After Smith's death, in 1968, the property was sold to a series of gringos who converted it into a $1,000-a-night resort, popular with U.S. senators, John Wayne, and Saudi sheiks.

After settling in, Runk, with help from a Tropic Star employee, found a motorista to take us upriver. We'd been under way for anhour when we arrived at a police station. There, a double-chinned comandante told us, “No one without a permit goes upriver.”

So we turned around and found ourselves a poacher. Carlos, an acquaintance of a Tropic Star employee, is a 37-year-old refugee who fled Colombia after, he said, “the paramilitaries started cutting off people's heads” in his village. He'd been living illegally in eastern Panama for nine years, supporting himself by hunting, also illegally, in the park. He wore a cobalt-blue tank top that read STALLION in big letters; at his waist hung a machete.

Carlos took us an hour west by speedboat to Punta Caracoles, a peninsula jutting out from the national park that teems with bush dogs, tapirs, and other tenacious wildlife. I'd been told that only the park's residents could hunt inside it, but Carlos, who lives in Jaqué, told me, “If I don't hunt here, someone else will.” He grinned. “Besides, I only take a little.”

Environmentalists consider poachers like Carlos, who are wiping out entire populations of peccaries, howler monkeys, and tapirs, a serious problem. “The greatest threat to the park is not some big entity like a multinational conglomerate or a development project,” says Líder Sucre, the thirty-something executive director of the Asociación Nacional Para la Conservación de la Naturaleza (ANCON), Panama's largest nongovernmental conservation group. “It's the fact that the park is huge, its staff is small, and there are hundreds and hundreds of little guys whittling away at it.”

After landing on a stretch of white beach, we plunged into the forest along a well-cleared path, which made me wonder how many hunters use this area. “It's not necessarily people who keep the paths clear,” Runk said. “It could be white-lipped peccaries,” a two-foot-tall species of wild boar weighing as much as 60 pounds.

I looked at Carlos, who was sniffing the air. “Do you hear them gnashing their tusks?” he asked. All I heard were the waves crashing on Punta Caracoles.

“It's quiet,” I said.

“That's because the other animalitos are hiding,” said Carlos.

“Watch out if the peccaries come our way,” said Runk. “Climb a tree, do whatever you have to do. You don't want to be gored.” As much as the peccaries scared her, Runk was hoping we'd see them, because, she explained, “a large herd of white-lipped peccaries is an excellent indicator of healthy forest.”

“What's a 'large' herd?” I asked.

“Oh, 200 animals. You'll definitely know they're coming.”

Suddenly Carlos hissed for us to be quiet. We heard a grunt from the undergrowth, then a rustle of leaves, then something pawing impatiently at the ground. Carlos yelled, “Run!” Which he and Runk did, but my legs had turned to jelly. A streak of brown fur tore out of the bush and hit me squarely on the calf.

“What was it?” I yelled, looking down and expecting to see blood. But there was no wound. The animal, which must have weighed about ten pounds, wobbled dizzily back to the bush.

“I think it was a ñeque,” said Runk.

“A what?”

“A ñeque. A little mammal. Sort of like a big rat.”

I looked into the forest and saw the dazed ñeque, gearing up for another charge. Then I noticed Carlos, who was laughing so hard he'd almost fallen on his machete. “I should have cut off his head,” he said, gasping for air. An hour later, we came across a poacher's campsite, an empty lean-to made of palm fronds, with the hunter's underwear hanging from the roof. Next to it, a campfire smoldered, and Carlos found two burlap sacks stuffed with smoked peccary meat. “This is too much,” he frowned, taking out a fist-size chunk of the meat, which he tore into strips and passed out to us.

That afternoon, as we hiked eight miles farther into the park, we saw more signs of a healthy forest: the footprints of a jaguar, one of the five species of cat that lives in the Gap; an ancient palm called a cycad; and, back on the beach, a clutch of sea turtle eggs buried arm-deep in the sand. Runk decided that the forest in and around Caracoles was “doing more than OK.”

“I've seen forest that's in worse shape,” she said. “A lot worse.”

War can be good for the environment—sometimes. In Poland during World War II, the wolf population increased substantially, and the Vietnam War gave the Vietnamese tiger an opportunity to rebound. One obvious benefit of armed conflict is that it scares people away from forest they might otherwise destroy.

Because of its proximity to the equator and its location between the continents, the Gap features an unusual mix of creatures, such as crab-eating foxes, brocket deer, and pumas, as well as an extraordinary level of biodiversity that includes at least 2,400 plant species and more than 900 species of mammals and birds. “There's nothing like it,” says Líder Sucre, of ANCON. “No other rainforest in Central America is as well-preserved.”

The trade-off is that Panama lacks access to South America and has no control over its own eastern border. Thirty years ago, the U.S. government decided this was an unacceptable situation. It provided more than $100 million to build a section of the Pan-American Highway connecting Panama to Colombia. The rest of the highway was already complete, stretching from Alaska to the southern tip of Chile.

The physical obstacles were daunting, including swamps deep enough to sink a ten-story building. Nevertheless, it wasn't the terrain but a virus, foot-and-mouth disease (FMD), that kept the project from going forward.

FMD is the doomsday plague of the livestock industry, an illness whose outbreak can shake global stock markets. Most recently, an epidemic of FMD ravaged England in 2001, causing more than $7 billion in economic losses. No cases of the disease have been reported in Panama, and the last U.S. outbreak occurred in 1929. But in Colombia, FMD was endemic during the 1970s and remains present today.

“If FMD were to invade Central America, it could have very rapid access to the United States,” says Harold Hofmann, 61, associate regional director of the U.S. Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), an agency within the Department of Agriculture that's charged with protecting the U.S. food supply from pests and diseases. “Therefore, the government's plan is to keep it as far away as we can.”

Because of concerns about FMD, in 1975 the highway plan was challenged in court by groups including the Sierra Club. The project was eventually scrapped. Meanwhile, yielding to pressure from the U.S., the Panamanian government established Darién National Park, in 1981, as a way to carve out a cattle-free zone in the jungle. Today, APHIS's $4.5 million regional budget covers the salaries of 90 Panamanian livestock inspectors who patrol the country looking for sick cattle. It also funds the battle against another potentially catastrophic South American scourge, the screwworm, whose larvae consume the flesh of live cattle, which can lead to fatal secondary infections. To control the insect, the agency drops a sterile male version of it from airplanes, in batches of 40 million, over the region every week.

“If screwworm got loose in the U.S., the effect on producers would be about $800 million lost per year,” says Hofmann. “Foot-and-mouth would far exceed that. It's a very dangerous disease—something we all fear.”

The good news is that Panama remains free of FMD and appears close to eliminating the screwworm; the bad news is that over the past 15 years the jungle on the Colombian side has shrunk.

“There's nothing left but cattle ranches,” says ANCON's Sucre.

Meanwhile, the forest on Panama's side is dwindling, too, thanks to an influx of Panamanian farmers drawn by the opening of the Pan-American Highway from Panama City to Yaviza, in 1988. Since then, eastern Panama's population has doubled, and essentially every acre of forest not on a mountainside is in danger of being cut down or burned—which is what makes protecting the park so vital.

Twelve miles up the Chucunaque River from Yaviza, continuing my December 2003 journey from there by dugout, the owner of the boat drops me in El Real, a weirdly inert village where a smiling pig's head, bobbing in the river, greets me as I step on dry land. Eight miles west of the park boundary, El Real is the headquarters for 14 dedicated but pathetically underequipped guards charged with patrolling an area the size of Puerto Rico.

At the ranger office—a wooden building with several basketball-size holes in the floor and a network of old PCs, none of them working—I meet Jorge Vásquez, 38, a Kuna Indian and senior park ranger. Vásquez is sinewy like a high school wrestler, and endearingly oblivious to how odd it may seem that one's desk sits next to a hole in the floor. Initially he tries to be upbeat about the park's troubles. “We're doing great!” he tells me, though some of the rangers have gone months without paychecks, and their gasless speedboat sits on blocks outside the station.

Later, though, after a few beers at a cantina in El Real, Vásquez confesses his frustration. “We can't do our jobs,” he says. “We don't have the resources or the security. You can't protect a park if you can't get around in it.”

I tell him about the satellite images, and he says he has a pretty good idea where the deforestation is happening. Back at headquarters, he shows me a faded wall map. “See here?” he says, waving his hand over virtually the entire border. “This belongs to the guerrillas. It's too dangerous to patrol.” He points at a different region. “This belongs to drug traffickers. We can't go here, either.”

Sometimes war isn't so good for the environment. Before the guerrillas invaded the park, the rangers maintained three monitoring stations; now they have only one, a mountain retreat called Rancho Frío. The others, abandoned to poachers and contrabandistas, “haven't been visited in almost a decade,” says Vásquez.

Meanwhile, refugees from Colombia have been pouring across the border. According to the Vicariato Apostólico del Darién, a local charitable affiliate of the Catholic Church, about 5,000 Colombians have immigrated to Panama over the past seven years, more than 300 of whom currently live inside or near Darién National Park. Those inside form clandestine communities that the church has tried to protect, because there's a high risk that they'll be killed if the Panamanian authorities send them back to Colombia. Manuel Acevedo, a human-rights activist at the vicariato, concedes that the refugees are among those burning forest, and that during the dry season “the amount of smoke coming from the park is tremendous.”

Vásquez and I decide to hike into the park; miraculously, the El Real police give us permission. “I'm going to show you what an amazing place this is,” Vásquez promises.

We leave El Real on a dirt road that cuts through farmland and rows of spiny cedar, take a shortcut beneath some barbed wire enclosing a herd of cattle, and walk through several miles of scrubby undergrowth. Then we enter the park, and suddenly, dramatically, everything changes. The trees are bigger, of course: We see several specimens of roble, a prized hardwood, that might be a few centuries old. The atmosphere is dark, wet, even chilly; Vásquez points out the footprint of a puma. It's like walking into a dark room and realizing, when the lights come on, that you've stumbled into a cathedral. There's practically no need for trails, because the ground appears to have been swept clean. We are in one of the rarest of all jungle settings, a true triple-tiered canopy. “What do you think?” Vásquez asks.

“It looks like God's greenhouse,” I say.

An hour after sunset we finally reach Rancho Frío. We'll have to camp here, because the police at a local checkpoint have threatened to arrest us if we keep hiking. “How much farther to where the deforestation shows up in the satellite images?” I ask Vásquez.

“A lot,” he says. Vásquez is dour, and at first I think it's because of the station, which is dirty and abandoned. But, as I soon find out, he has something much worse on his mind. Last year, just a day's walk away from here, the paramilitaries invaded Púcuro, a hamlet on the park's boundary, where he grew up. During that raid they brutally killed his father, Gilberto Vásquez, 58, a village chief.

The incident began on January 26, 2003, during a coming-of-age ceremony in Paya, a Kuna village inside the park. The paramilitaries, disguised as guerrillas, entered the village and requested a meeting with the chiefs. At the meeting they turned their guns on the hosts and said they were going to punish the Kuna for helping the FARC. Two chiefs and an unarmed Kuna policeman were executed. Afterwards, the paramilitaries stole the village's livestock, killed its dogs, and mined its paths so nobody could get in or out. Then they started marching toward Púcuro, forcing Gilberto Vásquez to serve as their guide. Someone had already alerted Púcuro, however, and the village was empty. So the paramilitaries shot Vasquéz in the head inside his own house.

No Panamanian police officers were in Púcuro or Paya the weekend of the massacre. Since then, however, security has greatly improved—in Púcuro and Paya alone, the police have added 100 officers—a development that Vásquez calls “the one good thing to come out of the killings.”

Yet many find the changes disturbing. “Panama used to be neutral regarding Colombia,” says Eric Jackson, the 51-year-old publisher of a muckraking paper called The Panama News, in Panama City. “Now it seems it is starting to take sides with the paramilitaries.” Villages thought to be guerrilla resting and staging areas have been ransacked and burned—not only by the paramilitaries but also by the Panamanian police.

“The government doesn't want people to know what's going on,” says Manuel Acevedo. “And so no one does.”

Vásquez and I leave Rancho Frío and return to El Real. Along the way, we pass through a few hamlets and chat with the remaining residents. “Most people got scared and left,” says one resident. In one community, the only inhabitant is a toothless old woman tending chickens.

Soon, though, we come across an abandoned village that is starting to fill up again. “Who are these people?” I ask Vásquez.

“Colombians,” he says. “Refugees.” One of the residents waves at us. He's wearing rubber boots and holding a Stihl chain saw. In his backyard, a little pile of brush is already burning.

Several months after my Yaviza visit, in March 2004, I return for another look. As soon as I arrive, I call the police and request permission to fly over the park to investigate the deforestation. Four days later I'm told that the national director of police, Carlos Bares, is personally “indisposed” to my request, because of the security situation along the border.

So I phone a tour operator, ANCON Expeditions. Loosely affiliated with the environmental group ANCON, the outfit flies ecotourists to an abandoned gold mine as far inside the Darién Gap as you can get, just five miles from the Colombian border. The mine, known as Cana, is halfway up a 4,000-foot mountain and 30 miles from the nearest town. It's so isolated that the police consider it too much of a hike for the guerrillas, and therefore safe for foreigners. The only way to get there is by plane.

A few days after my call, I squeeze aboard a charter carrying 14 American birdwatchers to Cana. During the flight over the park, all I can see are clouds, mountains, and a lush lowland rainforest.

At the mine, a path leads into cloudforest, and along the way I can see over waves of razor-sharp ridges into South America. Nothing but a horizon-spanning canopy and layers of dark rain clouds fill the view. From here, crossing the Darién Gap looks as formidable as a trek across the Sahara.

During my first night at the Cana Field Station, a converted mining camp, I wake up at 1 A.M., having soaked the bed in sweat. The next day my temperature is all over the place, and a worker at the lodge discovers me shivering in bed. “Uh-oh,” he says. “Looks like malaria.” I later find out it's hepatitis A combined with amoebic dysentery. The Darién Gap has started taking a toll on my body—I've lost ten pounds—so I'm extremely happy when a plane shows up the next day to take me back to Panama City.

I've been expecting its arrival: I chartered it before I left Panama City. Shortly before takeoff, I beg the pilots to let the ten-seat Islander “drift off course” by a few miles, and fly at a lower altitude.

Once in the air, the Islander starts its usual route west before banking sharply to the north. Instead of climbing, it remains wafting above the treetops, buffeted by columns of warm air rising out of the jungle. A low ridge signals our entrance to the Tuira Valley, and suddenly below us lies the landscape that the police so determinedly tried to shield from our eyes—the area revealed by the satellite images as a minuscule yet potentially catastrophic fracture in the otherwise perfect seal of the Gap.

To be fair, it hasn't been turned into a wasteland. More than a few trees remain. Here and there, in fact, it appears that the ecosystem is already on its way to recovery. But one would never describe this landscape as “forested.” On the contrary, it appears indiscriminately and brutally cut, and in many places burned. Moreover, much of the destruction looks fresh—new fires burn below as we fly over.

Going back to at least the 1880s, when the U.S. Congress passed legislation calling for a hemispheric system of railroads, the end of the Darién Gap has been confidently and even gleefully predicted. But, like the oceans, the Gap's resilience seems endless—and yet, as with the oceans, we know it is not. Sometime during this decade or the next—without fanfare, almost certainly—a milestone will be reached. The last trees will go down and the first breach between North and South America will open.

“How far to the border?” I ask the pilots. One of them unfolds a map and measures the distance with his fingers.

“About 20 kilometers,” he yells over the roar of the engines. Roughly 13 miles. Thirteen miles of dwindling Gap dividing the hemisphere in two.