DEEP IN THE RAINFOREST of northeast Guatemala's Petén state, within earshot of El Mirador—one of the largest of the ancient Mayan ruins—UCLA archaeologist Richard Hansen believes he's found the perfect spot for a tourist attraction. “I envision a high-end eco-lodge,” says Hansen, an internationally respected scientist who since 1978 has excavated sites in the Petén's sprawling Maya Biosphere Reserve. “There would be hot water for showers, clean sheets on the beds, and ice for your drink.”

Hansen isn't kidding, and his plans are notable both for their grandiosity and his professed motives, which are to protect El Mirador and other sites from looters, who cart off an estimated $50 million in Mayan artifacts from Guatemala every year, and to safeguard one of the biggest remaining tracts of intact forest in the country. After decades of watching the plunder, Hansen is convinced that the only long-term hope for preservation is to make El Mirador a paying concern and secure its borders with armed Guatemalan park guards trained by the U.S. Park Service.

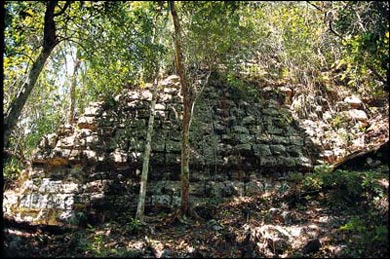

The development would be the centerpiece of a proposed Mirador Basin National Monument, an 820-square-mile plot of jungle that Hansen hopes to model on Tikal National Park, another Mayan site and Guatemala's top tourist attraction since the 1950s. He pictures a lavish wilderness lodge, complete with gourmet dining and an airstrip—enough infrastructure to accommodate 80,000 visitors a year. Though it all sounds far-fetched, in the past 16 months Hansen has nailed down the support of Guatemala's president, Alfonso Portillo, and other key government officials, rounded up close to a million dollars to dig major ruins out from under tons of dirt and get them ready for tourists, and kicked off a campaign to court international investment. It's far from a done deal, but he's made surprising inroads, and he's not letting up. “This is the pivotal year,” says Hansen, a bullish 50-year-old who made his name by proving that the Mirador Basin yielded Central America's earliest societies. “If I fail, the forest is gone and the sites will be destroyed.”

Hansen's plans put him at odds with local loggers and powerful green groups, who have their own ideas about preserving the region. For the past 12 years, the Petén has been the setting for a sustainable-forestry program launched with investment dollars from the United States Agency for International Development, a federal office that funds economic growth in developing nations. The goal was to give rural communities a stake in long-term forest health by granting them logging concessions. A number of U.S. environmental groups pitched in, among them the Nature Conservancy and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), spending some $40 million to teach locals about responsible forestry and promote their certified green timber on the global market.

But Hansen argues that the program has only hastened the destruction of the Petén and that new roads have made it easier for looters to transport Mayan treasures to market. “The grave robbers used to bushwhack in and cart out the artifacts on their backs,” Hansen says. “Thanks to logging roads, they've switched to pickups.”

In April 2002, after years of getting nowhere with his own idea, Hansen invited Portillo to the Mirador Basin and convinced him to nullify logging concessions that approach the archaeological sites—a critical step toward gaining national-monument status. This spring, he drummed up $880,000 from donors like the Global Heritage Fund, a California-based preservation group, to restore four buildings in the 2,500-year-old city of Nakbé. As of June, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), Latin America's largest lender, was considering Hansen's proposal to help finance a 13-year, $35 million investment plan to refurbish and guard the rest of the Mirador Basin sites. If the IDB commits, Hansen will be positioned to convince developers to invest in a lodge.

Not surprisingly, the plan has fierce detractors who, while conceding that the forestry program may facilitate looting, counter that Hansen's scheme would destroy years of successful collaboration between Petén communities and international nonprofits. “It reeks of neocolonialism,” says Darron A. Collins, 33, the Latin American and Caribbean forest coordinator for the WWF. “The gringo comes down, wraps up large chunks of forest, and builds a fence around it without considering the lives of local people.”

“Ninety-five percent of the people here are against him,” adds Israel Giron, the 46-year-old vice-president of Gibor SA, a logging company that lost 40 percent of its concession to Portillo's decree.

As inflamed Guatemalans see it, foreign investors will fatten up on tourist dollars while locals will be stuck cleaning hotel rooms. Hansen, who says he'll take no part in the financial operation of the development, insists they're wrong, claiming that tourism would contribute up to $20 million to the economy by 2020. But his macroeconomic arguments fall flat in the lawless Petén, where locals may be ready to take control of their future by whatever means necessary. After learning of an alleged plot to assassinate him, Hansen doesn't set foot in the jungle without four heavily armed Kaibiles—the Guatemalan equivalent of Green Berets—provided by Portillo.

Whatever happens next, the melee sounds painfully familiar to Arthur Demarest, director of Vanderbilt University's Institute of Mesoamerican Archaeology. In the late 1990s, he supported an IDB-funded tourist development at Mayan sites in Guatemala's Petexbatún region, and says the whole thing was a disaster. Roads were built and sites were restored, but locals were left out of the loop. Disillusioned, many returned to logging.

“People want the wood too bad,” says Demarest. “You'd have to put a wall around the entire Mirador Basin, and that's not going to happen.”