“HE SAYS HE’S NOT SURE we should do this,” said my translator. “That maybe it’s too dangerous.”

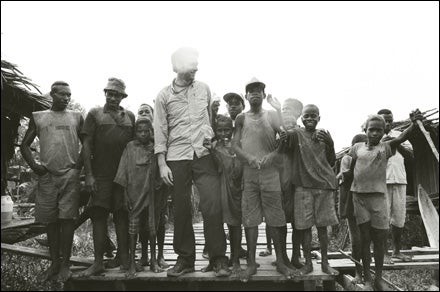

Per villagers talk to Tim Sohn in an unfinished yeu house.

Per villagers talk to Tim Sohn in an unfinished yeu house.

Per villagers talk to Tim Sohn in an unfinished yeu house.Arafura Sea

A storm moves over the Arafura Sea.

A storm moves over the Arafura Sea.Villagers at Momogu raise their paddles.

Villagers at Momogu raise their paddles.

Villagers at Momogu raise their paddles.These were unwelcome words, even more so because they were coming from Mr. Alex, a knowledgeable local we were relying on in this remote place thousands of miles from home.

I was a week into a trip through the Asmat region of the Indonesian province of Papua, on the southwest coast of New Guinea. There with a television crew, I was acting as a first-time host for a Travel Channel show called Gone Missing: Vanished in Papua, in which I planned to retrace the final journey of 23-year-old oil heir Michael Rockefeller, who disappeared there in 1961. Rockefeller had gone to collect intricate wood carvings by local artists for the Museum of Primitive Art, in New York, but as he was traveling along the coast with Dutch anthropologist Rene Wassing and two local guides in a catamaran fashioned from two 40-foot dugout canoes, a large wave knocked out the motor, and the craft eventually capsized. They drifted all night, at the mercy of the currents. The next morning, with a sliver of land visible, Rockefeller, in spite of Wassing’s protestations, decided to swim for it, using two empty fuel cans as floats. What happened to him next remains one of the 20th century’s great unsolved mysteries. Did he drown battling the powerful Arafura Sea’s tidal currents, or succumb to the sharks and crocs that inhabit the coastal waters? If he did make it to shore, was he then eaten by cannibals? Our goal was to re-create his final moments; if Rockefeller swam, so would I.

But first I needed to gather a little information. We were in Agats, population 1,100 and the regional hub of the Asmat, in the living room of Mr. Alex, a local merchant whose wife had prepared a delicious dinner for me and the other members of the crew, all from Los Angeles. There was Jeff Jenkins, 34, our longhaired and bearded executive producer; Nathanial Havholm, 38, a bespectacled and upbeat cameraman; and Dean Lee, 39, a fastidious and food-obsessed sound guy. Guiding us through it all, and translating Mr. Alex’s concerns, was Rufus Boropka, a Papuan from the Mayu region, a couple hundred miles southeast of Agats. We were discussing the details of the swim when Mr. Alex spoke up.

“He says we need to be careful of what’s the word?” said Rufus. “Sharps? Is it sharps?“

“You mean sharks?” I asked him.

“Yes, that’s it, sharks,” he responded. “The fishes that is always eating people, right?”

Fantastic.

But in the middle of my swim the next day, any fear of sharks was supplanted by a more pragmatic concern: Could I actually make it to land? I had my doubts: The green target= I’d hoped was solid ground turned out to be the ragged fringe of a mangrove swamp. I was plodding through thigh-deep water and tidal mud when the poisonous sea snakes showed up, as if on cue. The first one scared out from behind a tree to my left, behind Nat, the cameraman. Then, to the right, there was another one, ten feet in front of us.

Some long-dormant primate instinct kicked in: We took to the trees.

“I think this swim is officially over,” I said.

“Agreed,” said Nat. “Let’s get the ‘out’ ” the scene-capping bit of narration “and get back to the canoe.”

“I’ve made it to what I thought was the shore,” I was saying into the camera, swatting at mosquitoes, “but we’ve just encountered two water snakes, which is why I’m up in this tree.” Just then, I heard a branch breaking, a man’s stifled shout, and the sound of a splash.

Jeff, our producer, had fallen out of his tree.

Ahem. Take two.

MUCH OF THE TRIP, the bungled takes were a result of my own inexperience. I had never been on camera and wasn’t sure I was suited to it my whole career as a writer and reporter, after all, is about being an observer and blending into the background. My only real qualification to be a host was having written the October 2003 ���ϳԹ��� article on which the show was based. That had me even more worried, because I knew enough about the area to know that filming there would be difficult on its own merits, without the additional complications presented by a rookie host.

��

Traveling to the Asmat is like journeying back in time. First glimpsed in the 16th century by Portuguese explorers, New Guinea, and especially the Asmat region not seen by Europeans for another hundred years remained isolated by virtue of its inaccessibility, difficult topography, and notably unfriendly locals, gaining a reputation as a backwater populated by headhunters and cannibals. When Rockefeller arrived in 1961, the Asmat was home to one of the most primitive and least visited societies on earth. Today, any modern influences there coexist uneasily with older habits a man using a golf umbrella to shield a torch from the rain, a woman opening a can with a machete, a three-year-old toddler smoking, really smoking, a cigarette.

By the time I arrived, clean-shaven and stripped of my glasses, per network orders, I hardly even felt like myself. The plan was for me to ad-lib everything based on the research I’d done there was no real script, just a bullet-pointed outline that Jeff and I had put together. But on our first full day of shooting, I kept including irrelevant details and forgetting important ones. I mispronounced “avoid” as “aroid,” twice. I cursed, laughed nervously, reread my notes, punched the side of the canoe, and apologized to the crew.

Television required the unfamiliar skills of working with a group and processing everything in real time. Our first morning, we had set out to begin retracing Michael’s last river trip, but before we could leave Agats, the team wanted to record a piece recounting the town’s history and describing the journey. The idea was for the canoe to be moving action! while Nat kept the town in-frame over my left shoulder. Only, after every dozen or so failed takes, Agats would no longer be visible in the background and we’d have to circle back and start again. Television cannot be this hard, I thought to myself, can it?

“That one was good,” said Jeff finally. “Now I just need a little more out of you about how it’s the hottest you’ve ever been out here, something like that.”

“But it’s not the hottest I’ve ever been,” I countered, as combative as I was clueless. In truth, the heat was bad, and between it and the heavy humidity, we existed in a state of constant, sluggish dampness.

“Dude, come on,” said Jeff, “it’s pretty hot.” When we finally got it done, I looked over at Nat and Dean, two experienced TV hands, for their reactions. They looked worried. They had reason to be.

THE FARTHER WE GOT from Agats, the stranger things became, as the villages grew gradually more primitive and less accustomed to visitors. It didn’t take long in any village for news to spread that the aliens were coming. In one, when I asked if they often had visitors like us, the elders pondered a bit. “Yes, they say they have many visitors,” Rufus translated. “Two this year.”

Jeff held a particular fascination for the locals owing to the ministrations of missionaries, his long hair and bushy beard made him a ringer for the one white man that most of them knew by name. They enjoyed practicing a few words of English on him: “Hello, Jesus Christ! Nice to meet you.”

As we grew more comfortable, I grew more competent, and things began to click. By day three I’d begun to enjoy myself as I dug into the reporting and, more surprisingly, discovered an inner TV persona I didn’t know I possessed. We found people whose parents had sold skulls to Rockefeller and men who remembered the bespectacled foreigner. We interviewed one of the two “boat boys” who had been with the heir on his catamaran just before he disappeared. The process wasn’t flawless: During that interview, as I was sitting on his hut floor on the riverbank in the village of Sjuru, I looked away from his ancient face, shrouded in the smoke of his cigarette, to see Nat wiping the camera’s lens with his T-shirt. The humidity, exacerbated by a dozen people jammed into a 12-foot-by-12-foot hut, had gotten to the camera, and there was condensation inside the lens. We paused the interview and switched to our backup camera.

“This one’s all fogged up, too,” Nat said, 20 minutes later. “Nothing I can do. But I got plenty of good stuff before it went.”

Having a routine helped maintain some normalcy. At each new village, Rufus would disembark first and explain what we were doing. We’d usually shoot one piece outside and then go into the village’s yeu (pronounced like “joe”), the traditional, male-dominated longhouse that sits at the physical and cultural center of every Asmat village and serves as kitchen, community center, house of worship, hostel, and overall nexus of life.

While filming in a yeu was difficult, sleeping in one was nearly impossible. The Asmat sleep little, believing that their spirits leave their slumbering bodies and commingle with the spirits of the dead. Every night was a chorus of mosquitoes, dogs yelping, pigs rooting around under the floor, babies crying, old men coughing and laughing, and fires being stoked. Yeus have no chimneys; keeping the smoke in helps keep bugs out and preserves food but contributed to mornings of coughing “yeu lung,” we called it.

But the welcome and the warmth of the people (most of the time) more than made up for any discomfort. All the locals asked for in return was answers about our own culture.

“He wants to know where you are from, and how you got here,” said Rufus, translating a question from one village elder. I didn’t know where to begin, so I let Rufus take over.

“I telled them that where you come from, it is so far away that when the sun is going down here, it is coming up there,” he said, explaining the distance between us. “I said that you are from the other half of the world.”

I KNEW I HAD ACHIEVED a sort of Asmat state of grace when I found myself actually enjoying the periodic downpours.

“It’s like turning the showerhead to the massage setting,” said Jeff as we motored into a storm one afternoon. “It actually hurts.” Jeff was in a particularly good mood, since earlier in the day we’d bagged one of the shots on his “must-have” list: a crocodile sliding into the water. He had mentioned it so much that we were all on the lookout, but Rufus was the only one eagle-eyed enough to spot it. We were headed upriver when he pointed to a muddy spot on the riverbank and whispered, “Crocodile.” Such serendipity began to seem normal.

Just as that afternoon’s storm let up, I heard a rhythmic chanting coming toward us over the water “Huhh, huhh, huhh, huhh, ah-uhh” accompanied by the sound of wood slapping wood. Looking toward the noise, we saw a dozen dugout canoes, each with six to eight men, coming across the misty water. The men paddled standing up and were decked out in the garb of a war party: headbands of cuscus fur and cassowary feathers, boar-tusk pendants, and a smattering of cassowary-bone daggers tucked into the woven-palm armbands that they wore on their biceps.

“They’re coming out to meet us,” said Rufus. This explained little, and I had a moment of genuine fear. A flotilla of Asmat canoes is an intimidating sight, but as they closed in I recognized many of the men from the village we had stayed at the night before.

“Nat, can you shoot?” Jeff asked.

“Yep, good to go.”

“There’s no way we can get sound, can we?” Jeff asked, looking to Dean.

“I think so. Tim, you still on?” Dean asked, referring to my microphone pack. I nodded. “Yeah, let’s do it.”

As I began narrating, the rain let up and a half-dozen canoes fell in on either side of us. On our left, a couple of wily elders held on to our gunwale and let our outboard do the work for them. When I was done narrating, I found myself banging my hand against the side of our canoe in time to the chanting.

“I feel like I’m vibrating right now,” said Nat, exhaling deeply, a big smile on his face.

Jeff turned to me and held up his hand for a high five. “Print that!”