����

Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea

Porters descend the treacherous slopes of Ghost Mountain.

Porters descend the treacherous slopes of Ghost Mountain.Papua New Guinea

Local guide Berua crosses the Mimani River with his hunting dog, ax, machete, and boar spear.

Local guide Berua crosses the Mimani River with his hunting dog, ax, machete, and boar spear.Papua New Guinea

Laruni village, where the author rejoined the trek via helicopter

Laruni village, where the author rejoined the trek via helicopterI’m lying in a bark hut surrounded by strange men. One sits smoking pungent tobacco rolled into a long, fat spear, a caricature of a Rastaman’s joint. Two others chew betel nut, their mouths a bright, frothy red. Curled up in the corner, my friend George Houde is sleeping the sleep of the dead while rats play at his feet.

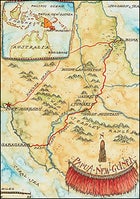

Sidelined by a steep, muddy trail and a bad fall, we’re here because I tore my ACL while attempting a 130-mile trek across Papua New Guinea. Now George, a reporter on leave from the Chicago Tribune and part of our eight-person team, and I are back in the inland village where we started our trek on foot. My goal of following in the footsteps of a group of World War II soldiers via what they called the Kapa Kapa Trail (a mispronunciation of Gabagaba, the coastal village where the route begins), which runs across Papua New Guinea from its south coast to its north, is in serious peril. It’s the first day of the trip.

In October 1942, during a march considered one of the cruelest in modern military history, 1,200 ill-equipped, untrained American troops from the 32nd Infantry Division endured more than a month of suffering on the Kapa Kapa en route to the north-coast battlefields at Buna, where the Imperial Japanese Army was waiting.At least two men died of exhaustion during the crossing, and the rest were physically shattered by the trek. Remarkably, after nine weeks of fighting in stinking, hip-deep swamps full of floating corpses bloated by the heat, the Allied troops finally dislodged the Japanese from Buna. But the victory came at a cost. According to General Robert Eichelberger, the commanding officer, fatalities “closely approached, percentage-wise, the heaviest losses in our own Civil War battles.”

The soldiers’ memories are still searing. “If I owned New Guinea and I owned Hell, I would live in Hell and rent out New Guinea,” says Buna veteran Bob Hartman.

I’m beginning to see what he means. Three years ago, while researching a book on the soldiers’ experience, I hatched the idea of repeating the WWII march. If the trek succeeds, it will be the first time in 64 years that a team from outside Papua New Guinea has hiked the trail in its entirety. I’d visited New Guinea four previous times, the last trip just ten months ago, when I came to scout the area. I was advised then by former Australian colonial patrolmen, the Papua New Guinea Defense Force, and a number of trekkers familiar with the New Guinea bush not to attempt the crossing. Even if the route had not been consumed by jungle or erased by torrential rains, I was told, it was at best nothing more than a narrow hunting-and-trading trail that traversed some of the country’s most formidable territory. One villager looked into the mountains and whistled through his teeth, “Long way too much.” A former government patrolman challenged my sanity. “You’re delusional,” he said.

The Australians had counseled General Douglas MacArthur against sending men on this route, too the mountain passes were too high, the terrain too rough, the rivers too fast, the tribes unpredictable.

But they went, and now so have I. The sun drifts below the mountains, and the evening is stifling. Dela, the hut’s owner, inexplicably refuses to prop open the thin bamboo boards that serve as windows. When I persist, he explains in a mix of English and Motu that there are sorcerers who roam the hills at night, cast deadly spells, and will try to kill me. Just then I hear soft voices outside the hut. Dela opens the door and villagers file in with bowed heads, as if in prayer. They begin to sing, in two-, three-, four-part harmony. It’s as if angels have descended.

Perhaps our luck is turning, I think. The next morning, George and I walk out of Dela’s village to a rutted road and jump in the back of a truck. After a series of bone-jostling rides we arrive back in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea’s capital city, where I buy anti-inflammatories and painkillers and plot with George about how we can continue the trek. Could we meet up with the rest of our group by plane? “Impossible,” a pilot we approach tells us. With a helicopter, though, he thinks we stand a chance.

Seventy-two hours later, as we hover in a chopper over a vast jungle canopy broken only by rivers spilling out of murky mountains, the sight of so much raw wilderness has me second-guessing my decision. I’ve never seen the likes of the Kapa Kapa Trail.

DESPITE ITS PROXIMITY to Australia, New Guinea is geologically a much younger land. Shaped by the explosive tectonic forces of the Pacific Ring of Fire and carved by near constant rain into a tangle of swamps, trackless ravines, and 12,000-foot mountains, it is one of the most rugged and mysterious places on earth.

The world’s second-largest island, New Guinea is divided between two countries. The western half, originally colonized by the Dutch, has been part of Indonesia since 1969 and is called Papua (the name was changed from Irian Jaya in 2002). Since gaining its independence from Australia in 1975, the eastern half, roughly the size of California, has been an independent nation called Papua New Guinea (PNG). Though tourism is still in its infancy, adventurous travelers visit PNG for wreck and reef diving, sea kayaking along its incredible coastline, and the chance to see birds found nowhere else in the world. For the ultra-adventurous, New Guinea offers challenging treks, mainly on the Kokoda, a 60-mile WWII trail, 40 miles northwest of the Kapa Kapa.

Still, vast swaths of the island remain unknown, and it’s hard to imagine what WWII soldiers might have encountered here. In 1942, the Japanese landed 11,000 troops on the Papuan Peninsula’s north coast, hoping to use New Guinea as a stepping stone to invade Australia, or at least to disrupt the supply lines from the United States to the South Pacific. MacArthur, who had been spirited out of the Philippines in March 1942 to command the Allied forces in the southwest Pacific and lead the Army effort against the Japanese, sent in Australian soldiers to stop them. Two months later, with the Japanese gaining a stronger foothold on the peninsula, MacArthur ordered a battalion of the American 32nd Division to cross the treacherous Owen Stanley Range and fight them at Buna. None of the men had spent a single day in the jungle.

Nor had I, but our team contained no slouches. I had logged hundreds of miles on foot and snowshoe through Arctic Alaska while researching my first book, and had been hiking with an 80-pound pack for eight months prior to this trip. Besides George, a 58-year-old long-distance runner and biker, our expedition group consisted of Dave Musgrave, 54, a wilderness expert and professor of oceanography at the University of Alaska Fairbanks; Philipp Engelhorn, a fit 37-year-old Hong Kong based photographer; Lee Ticehurst, a 55-year-old Aussie expat living in Port Moresby and an accomplished jungle trekker who has completed the Kokoda three times; a young three-man film crew (Cal Simeon, Jack Salatiel, and Kenneth “Samu” Pasiu) from Port Moresby based POM Productions, there to shoot a documentary; and teams of porters hired in various villages along the way to carry our food and camping gear.

It took the WWII soldiers seven weeks to reach the north coast. They walked for more than half of those days; the rest of the time, they recuperated in villages and waited for food and supply drops. The Army’s decision to let the men rest seemed practical at the time, but it backfired. The soldiers were already suffering from dysentery, trenchfoot, and jungle ulcers when malaria hit them like a bomb. Eventually, 70 percent of the division would contract the disease.We decided to walk considerably faster, even if it meant putting in 10- and 11-hour days on the trail. Concerned about malaria and battery power for the film equipment, our plan was to reach the end at Buna village in two to three weeks, limiting our exposure to the jungle.

IT IS IMPOSSIBLE TO AVOID superlatives when talking about New Guinea. Four days into the trek, the team enters a rainforest whose biodiversity is nearly unmatched worldwide. Among its avian species is the bird of paradise approximately 38 of the world’s 40-odd species live here. It is also home to more than 3,000 species of orchids, the world’s largest butterfly, its largest moth, the smallest parrot, the largest pigeon, and the world’s longest crocodile. The jungles of New Guinea’s Papuan Peninsula, in particular, support such an astonishing assortment of trees, ferns, mosses, bromeliads, frogs, butterflies, and rare, night-loving marsupials that the World Wildlife Fund has submitted a proposal to UNESCO to include the entire Owen Stanley Range on its list of World Heritage sites.

��

Joining our team to guide us over the mountains is Berua, a bone-thin, jungle-wise man whose parents served as carriers for the GIs on the Kapa Kapa. Only seven years old at the time, Berua struggled with them across the spine of the Owen Stanleys en route to the remote community of Jaure. Berua’s tattooed 65-year-old wife, Bima, and his hunting dog also join us.

With Berua at the front, we follow the rushing Mimani River into the sodden heart of the rainforest, where sunlight dimmed by a dense mesh of trees, leaves, vines, and fronds has turned the jungle into an immense boiler room. If I was worried about Berua and Bima keeping pace, I shouldn’t have been. Papua New Guineans spend their lives walking. For most, it is their only mode of transportation.

We bivouac at the river’s edge. Our bush camp consists of a large, blue plastic tarp thrown over a ridgepole, supported by two more poles and tied down to ground pegs. We clear the area of sticks, rocks, and roots and then lay large leaves over the moist ground. I can see George, who is playing the role of expedition skeptic, eyeing the shelter, wondering what is going to keep the snakes out. Twenty-foot pythons and “one-cigarette” snakes like the taipan whose bite will kill you before you have time to finish a smoke lurk on the Papuan Peninsula.

Soon darkness presses in, tight and coal black. As if to underscore our vulnerability, the forest becomes an opera house as millions of crickets, cicadas, frogs, “singing” worms, and other strange, boisterous insects and animals wake from their afternoon slumber. As we place our sleeping bags under the tarp, Dave stumbles out of the bushes. He’s spent the past 25 years exploring Alaska’s remote wilderness areas, but he’s never seen a night like this. It is so dark, he says with a laugh, that he couldn’t find his pecker to piss with.

Concerned about my knee, I begin walking early the next morning while the team breaks camp. We face a grueling hike to the 9,500-foot summit of what the locals call Mount Ororo. As I climb, a maze of spiderwebs tickles my hands and face. Massive trees, with trunks the size of silos, adorned with lianas and wrapped in a swarm of vines resembling large pythons, reach for the clouds. Less than an hour into the hike, though, I am incapable of admiration. I’m on all fours, pushing through the mud, grabbing at roots, trees, ferns, bushes, leaves, anything I can clasp with outstretched fingers to keep from falling backwards down the steep, slippery mountain. In a cruel twist, everything I reach for is equipped with spurs, thorns, tiny sharp bristles, or swarms of red ants, and my hands sting and bleed.

The porters approach behind me, calling to one another in excited, high-pitched voices, and skip by as if their 40-pound loads weigh nothing. They are off-trail, jumping over downed trees while trying to locate Berua’s dog. They do all this without shoes, on broad, thick-skinned feet that make a mockery of my new jungle boots.

Entering the cloudforest, I encounter a scene that inspired the spooked American soldiers to dub Mount Ororo “Ghost Mountain.” In the heavy fog, the huge, moss-draped beech trees look like apparitions. Ghost Mountain is soggy, sunless, and silent, suspended in perpetual twilight. The team has caught up with me, and we crest the mountain together. At the top, George quickly notices that the trail catapults down the mountain alongside a steep cliff. “That’s comforting,” he says. “We might as well throw ourselves off right now.”

Cal, one of the young cameramen, apparently takes this as a cue. He grabs a vine as thick as my arm, lets out a deep-woods yodel, and swings out over the cliff and back. He beams. I decide he’s been driven mad by the jungle.

To lessen the punishment of the descent, I ride the stream of mud on my backside. Tiny leeches attach themselves to any bare skin they can find and gorge on my blood. Even the porters are tired when we make camp late that afternoon on the slopes of Ghost Mountain, but it’s clear they don’t want to stop here for the night. It’s cold, the wood is wet, fires are hard to start. What’s more, they believe that high mountain regions are populated by masalai, or evil spirits. Through the night I wake periodically to find the porters smoking tobacco out of flute-like bamboo pipes, unwilling to sleep.

BY DAY TEN WE’RE NEARING SUWARI, the most remote mountain village we will encounter. Our 1:100,000 scale topographic map shows a dense jumble of contour lines and three large white patches that read OBSCURED BY CLOUD. The map was compiled by the Royal Australian Survey Corps more than three decades ago and has not been updated.

��

As we walk through fields of sweet potato, corn, and banana trees, a sentry spots us and blows on a conch horn to announce our arrival. Drums boom, rattles cackle, and in a small dirt opening a group of people begin to dance. The men are decorated in elaborate bird-of-paradise headdresses and necklaces of pigs’ tusks, their bodies rubbed with black oil; they lunge at us with wooden spears, their tongues shooting serpentlike from their mouths. The women dance bare-breasted in woven grass skirts, shrieking as they swing axes over our heads. The soldiers never got to see such a display. In fact, American WWII maps list Suwari as deserted. When the villagers saw the soldiers coming, they fled to nearby caves.

One of the dancers approaches and introduces himself as Giblin. In broken English he explains that the village had learned that a group of taubada, or white men, was on its way, and they had organized the ceremony in our honor. At one time, he says, the dance was performed as a celebration after a successful raid. Having captured or killed their enemies, warriors would return to dance and to feast on human flesh. Smiling, he assures me that his people have no intention of eating us.

That night, crowded into the open-sided “house of wind,” Giblin lights the village’s only lamp, a sure sign that we are honored guests kerosene is a four-day walk away. We are, he says, the first outsiders to visit Suwari since 1975, when Papua New Guinea gained its independence. Prior to ’75, Australian colonial patrols used to make infrequent visits, imposing on the distant mountain villages a Western economic structure and the British system of law. The patrolmen occasionally doled out harsh justice, but they also brought medicine, tools, and contact with the outside world. Now the village is suffering no school for the children, no employment opportunities, and a high incidence of malaria, tuberculosis, skin diseases, and infant mortality. Had Suwari been more accessible, Giblin’s people might have sold their pristine forests to logging operations. Because of its location, though, Suwari is putting its hope in the Kapa Kapa Trail. Perhaps it will bring taubada with money.

After years of promotion, the Kokoda Trail, on which the Australians fought the Japanese, now draws 2,000 trekkers a year to Papua New Guinea. The World Wildlife Fund and the Kokoda Track Authority have joined forces to begin turning the trail into a model of sustainable ecotourism. Though there have been problems erosion, siltation, the clearing of forests for firewood and though the track authority worries about the loss of cultural identity among the people of the Kokoda, the trail has been a success. A new plan calls for the training of guides in expedition skills, English, history, environmental stewardship, and the promotion of native culture, architecture, and craftsmanship.

Giblin is not aware of any of this, yet he already has a plan for the Kapa Kapa. His village will build a guesthouse, the young men will make money as carriers, the women will sell fruits and vegetables, the villagers will take trekkers on birding expeditions, they will don traditional tribal costumes and dance and sing. The question is, will the taubada come?

Giblin tries to convince us to stay an extra day. It is mating season for the bird of paradise, and soon the gaudy males will be dancing on their forest perches, courting females. Although tempted by the chance to see one of the world’s rarest birds, we press on.

GEORGE HAS-ALL OF US WORRIED. He has developed dangerous skin ulcers on both legs. Despite the pain, he insists on trying to complete the remaining three days of the trek, but we need to get him out of the jungle fast. Jack isn’t in great shape either. His feet are cracked and bleeding. Cal’s knee is giving him trouble. Lee looks pale and tired (is it the onset of malaria?). For all intents and purposes, I’m walking on one leg. Only Dave, Samu, and Philipp are holding up, but if the trail lives up to its reputation, their turn is bound to come.

The thing about the jungle is that often you can see nothing but more jungle. But on day 14, having negotiated the fierce currents of the Musa River and the crumbling, volcanic slopes of 5,512-foot Mount Lamington which erupted in 1951, killing 3,000 people we reach the Girua River. The clouds have lifted, and we look up the river valley, getting our first glimpse of the territory we’ve covered. Ahead, the flat coastal plain sprawls north under a battering tropical sun. Though the worst is behind us, from here the trail slices through fields of head-high, razor-sharp kunai grass and wanders back and forth across the river. It will not be easy, but the end is in sight.

Two days later, after 16 days in the jungle, we reach Buna.

The Kapa Kapa, which we’ve renamed the Ghost Mountain Trail, is, as Lee concludes, “the Kokoda on steroids.” For the weary soldiers and the hundreds of New Guineans who served as carriers and scouts for the Army, the end of the trail was the beginning of a long nightmare. When they arrived in Buna, they entered tangled, tea-black swamps and a battle that General MacArthur described as a “head-on collision of the bloody, grinding type.”

Papua New Guinea tourism officials told me that they hope to promote this history and, in light of our success, turn the route into something like a national historic trail. The World Wildlife Fund currently has plans to incorporate the Ghost Mountain Trail into its blueprint for conservation and tourism in the Owen Stanley Range.

For their part, the WWII veterans can’t imagine anyone ever choosing to walk across Papua New Guinea. “Are you kidding?” 32nd Division member Stanley Jastrzembski said to me. “I would have taken an enemy bullet before going back into those mountains.”

But none of us regretted a mile of it.