WE ARRIVED AT NEW DELHI'S Shanti Home hotel late at night, en route to Nepal, six men and a manager with almost zero experience about to belly-flop right into the 27th World Elephant Polo Championships. Thrilled to learn that he had America's elephant-polo team in his midst, and of course having no idea how important this actually was, Rajat, the Shanti's charming and mustachioed proprietor, gathered his staff in front of a statue of Sarasvati, the Hindu goddess of learning and the arts.

World Elephant Polo Championships

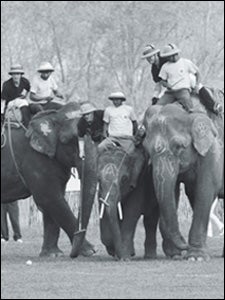

The author's team, the New York Blue, in a “muddle” for the ball against the British Gurkhas

The author's team, the New York Blue, in a “muddle” for the ball against the British Gurkhas╠ř

“I think there is a 100 percent chance that you will win, and to help your chances we will say a prayer,” he said. Then a bell was rung, a conch shell blown, and Rajat announced┬Świthout bothering to ask if indeed there was a trophy or what form it might take┬Ś”The cup is yours.”

He uncorked a bottle of champagne and continued, “In India, we have a saying that if you believe in your mind that you have already won, and you celebrate in advance, that you will win.” He smiled, his white teeth sparkling in the moonlight. “It's like count your chickens before they hatch,” he said, adding, “Whatever you do, you must do it with great aplomb.” Then he finished his flute of bubbly, downed a few more drinks with us, and went to bed.

Now, this much should be told: Prior to our arrival in Nepal the following day, only one member of our squad had played elephant polo, in a brief exhibition. The rest of us had neither sat atop an elephant nor played horse polo nor spent much time atop a horse. We had “practiced” twice at a windswept parking lot along the beach in Queens, New York, in bitter cold, using mallets fashioned from PVC pipe and riding on top of SUVs in place of elephants. It was funny but not entirely helpful.

And so, last November 30, two days after Rajat declared our success imminent, we┬Śthe New York Blue, representing New York City and, without its knowing, the United States┬Śbegan our long-shot campaign at the Tiger Tops Jungle Lodge, the oldest safari camp in Nepal. Our first opponent was the world's perennial number-one-ranked team, Chivas Regal of Scotland. That Scotland is best in the world at a sport that involves elephants is of course ridiculous, but it makes a little sense when you consider that Chivas Regal, a whisky, is the tournament's longtime sponsor and that one of the sport's two founders, James Manclark, is Scottish.

Our starting four were: me; Bill Keith, the deputy editor of Out magazine; Rob Forster, an investment-banking lawyer; and Chip Frazier, a recently unemployed hedge-fund trader. (On our bench: Bryan Abrams, a Playboy researcher, and Jeff Bollerman, an investment banker with Citibank.) The Chivas team was: the 13th Duke of Argyll, who has 29 honorifics and, if you are British and abide by such puffery, is to be called, upon first reference in a text, His Grace the Duke of Argyll, Torquhil Ian Campbell; Raj “the Silver Fox” Kalaan, a former star of the Indian national polo team and a colonel in the world's last mounted regiment; Peter “Powerhouse” Prentice, Chivas Brothers' vice president for Asia, a 20-plus-year veteran of the sport and a man whose business card bears, in letters the size of his name, W.E.P.A., for World Elephant Polo Association; and Indra Muggar, a Nepalese ringer who could easily play without the services of his mahout, as the driver-operators of the elephants are known.

Kristjan Edwards, 39, captain of the Tiger Tops team, son of the sport's overlord, A.V. Jim Edwards, and a Peter O'Toole lookalike who smokes like a chimney, shook his head the first morning when he heard that we'd drawn Chivas. “Baptism by fire,” he said.

ELEPHANT POLO is believed to have been played for many years on the subcontinent, but it wasn't formalized as a “sport,” if you can call it that, until 1982, in a bar in St. Moritz. There, A.V. Jim Edwards, owner of Tiger Tops, was having cocktails with Manclark, a bon vivant who competed in luge at the 1968 Olympics and once tried to circumnavigate the planet in a hot-air balloon. Manclark loved polo. Edwards owned elephants. You can connect the dots.

The two men founded WEPA, concocted the rules, and presided over three annual tournaments, held in Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Nepal. The Sri Lankan event no longer exists, so these days it's just a two-tournament season, with the Nepal event, held in late November and early December on the Tiger Tops airstrip, serving as the capstone.

Teams need to meet only two criteria to play in the championships: (1) A.V. Jim Edwards must decide you're worthy, and (2) you must be able to pay the $9,200 entry fee, which so far as I can tell is pretty much the key to number one. Ten teams had been expected for the 2008 event, but only eight showed up as the ripple effect of the global economic meltdown worked its way out to elephant polo. There was one other team of first-timers, the Pukka Chukkas, Brits and Aussies who were every bit our match at the Tiger Tops bar. Another squad, the Air Tuskers, had pulled out after its sponsor hit the skids but was rescued from the embers by Robert Mackenzie, a wealthy Englishman who sold his company to Warren Buffet in the late nineties and has been having a helluva time ever since, flying around in helicopters and trying to qualify for the Seniors Tour in golf.

Play is similar to that of horse polo, with four riders per side, but there are some major differences. The field is shorter┬Ś100 meters long, compared with a 300-yard horse polo pitch┬Śand games are brief, just two ten-minute chukkers (a.k.a. chukka, which is polo for “period”). The elephants are organized into four groups of four┬Śknown as A, B, C, and D┬Śand during the 15-minute break between chukkers, teams switch ends and elephants, to eliminate advantages both meteorological and zoological.

There are some key rules: No more than three elephants per team can be in a particular half of the field at one time, and only one elephant per team may enter the 20-meter-deep semicircle zone around each goal, known as the D. If the offense violates this, the defense gets possession. If the defense is the culprit, the offensive team gets a free shot from the spot nearest the violation on the D. It's also illegal for an elephant to lie down in front of the goal.

The elephants are “driven” by local mahouts, with competitors riding behind them barking directions. On the smaller elephants, the popular way to mount is a Lone Ranger┬ľstyle run-and-jump. The elephants kneel for this process, which is adorable, and to scale the bigger ones you must step on the tail, then the leg, and clamber awkwardly up its back until the mahout lashes you to the burlap saddle with a thick rope. The elephant stands up almost immediately, so this procedure can be terrifying until you get it down.

To lessen the strain on the animals, the tournament takes place over five mornings. No elephant may play consecutive games, and matches must be completed by noon, when the heat begins to set in. To keep the animals fueled, and to offer some incentive, an official rule states that “sugar cane or rice balls packed with vitamins (molasses and rock salt) shall be given to the elephants at the end of each match.” The mahouts are to be given soft drinks.

The Nepalese National Parks provided half of the 16 elephants (the lodge is inside Royal Chitwan National Park), while the other half were selected from the fleet of safari animals owned and operated by Tiger Tops. Of course, it seems absurd, if not cruel, to force elephants to play polo, but I was happy to see that they are very well treated, almost doted upon, by their mahouts, who care for an elephant for life in teams of three. Also, a chunk of the money raised by the steep tournament fees goes to elephant welfare in Nepal, which has roughly 100 to 125 wild elephants remaining after years of poaching and habitat loss.

In a nice bit of unintentional symmetry, the New York Blue was founded in the same manner as the sport┬Śover cocktails. It was the winter of 2007, and my friend Bill Keith, then a freelance writer, was sitting on a barstool in Anguilla regaling Melanie Brandman, the owner of a New York┬ľbased luxury-travel PR firm, with an account of the 2005 World Elephant Polo Championships, which he'd attended on a junket. He told her that, one afternoon on the pitch, he'd expressed disappointment to the wife of the then U.S. ambassador to Nepal that his home country wasn't represented. “You should start a team,” the ambassador's wife had responded. In the ensuing two years Bill had talked of this mythical journey with some regularity, telling the eventual members of Team Blue that we were going to enter. (We were fully on board but skeptical it would ever happen.)

As it turns out, Brandman is a spiritual lady, and her psychic had recently predicted that “elephants would play an important role” in her life. When Bill told her his story, it clicked.

“I can find sponsors to make this happen,” she said, and the two clinked martini glasses.

I got a text from the Caribbean: “Elephant polo is on.”

WE STARTED with a 5┬ľ0 lead over the Scots, thanks to a handicapping system intended to level the field. From where I sat, ten feet in the air atop a gentle, lumbering elephant and clenching a wobbly cane mallet almost six feet long, it hardly seemed enough. It's difficult to overstate how awkward and unnatural it is to work from such a walking, breathing precipice. I thanked God I wasn't driving.

I looked around at the remainder of our starting four┬ŚBill, Chip, and Rob. They looked ridiculous if nattily attired in our improvised uniform of navy-blue polo shirts, white button-fly Levi's and navy-blue Converse Chuck Taylors.

Since the New York Blue had no skill, our only chance was to pack three of our elephants into the defensive half and engage in “muddles,” as the scrums for the ball are known. As you might imagine, six elephants carrying 12 humans┬Śhalf of whom are flailing with sticks at a softball-size ball ponging around 24 elephant legs┬Ścan create a bit of a clusterfuck. Eventually the referee, sitting on a platform erected on his own massive elephant, would whistle the play dead and order a restart.

It took us a good chukker to realize that the elephants made as much difference as the skill of the players. They came in all speeds and sizes and seemed to apply effort in fits and starts. Some even refused to play with others. There were also disparities between the four elephant groups. The A and B elephants were roughly equal, but C and D were hugely different. Elephant for elephant, C was faster and more agile, seemed more motivated, and tired less easily. D featured one star elephant, a tiny little guy who zipped around like a sports car, but he fatigued quickly and by the second half was a shell of his former self.

Against Chivas, we started out on D, with them on C, and they scored five times to tie the match before the break. But after switching animals, we shut them down late into the second chukker. We didn't muster much offense, but it hardly mattered. Our elephants were faster to loose balls, and Chip, our unemployed trader, was a monster on defense, using his smaller, speedy new elephant to clear challenges from our goal area before the Duke or the Colonel or the Powerhouse could get off decent shots.

With just a minute left in the match, the Powerhouse cracked one into the goal from well outside the D, raised his arm, and howled. Chivas prevailed, 6┬ľ5.

Afterwards, A.V. Jim Edwards summoned the teams to his double-wide tent, complete with a cushioned wooden armchair, cot, and changing room and festooned with a giant yellow banner reading WEPA HEADQUARTERS I/C JIM EDWARDS. Son of a potato farmer from the Isle of Jersey, he took over Tiger Tops in 1971. By 2008, he chaired a group that oversaw four lodges and employed some 700 Nepalese. Until a stroke three years ago, he played alongside his son. The event was obviously the highlight of his year.

“You guys have about 200 hours of elephant-polo experience,” Edwards said to team Chivas. “These guys, seven minutes.”

“It just goes to show the handicap works pretty well,” said the Duke of Argyll, clutching a Carlsberg in his non-mallet hand. (For a good hour after each match, one's mallet arm is shaky and weak and essentially useless.)

Edwards corrected His Grace: “I'd say it's perfect.”

“THIS IS NOT an easy game,” warned Colonel Raj Kalaan, the former stud of the Indian national horse-polo team, moments before our second match. “There are three minds┬Śyours, the mahout's, and the elephant's.”

As newbies, our disadvantage in negotiating this mental triangle was never clearer than against our next opponents, the National Parks team. A collection of local players, some who work with elephants daily, they spoke Nepali and could give their mahouts directions (“Turn left,” say, or “The ball is under us,” a common problem) instead of using the tourist method, which is to scream loudly in English and pound the poor guy on the back. The mahouts in turn communicated with the elephants, which understand between 50 and 100 words of the regional Assamese language and move based on which ear its driver presses on with his bare feet. For the most part, the elephants seem to know what's going on anyway; they naturally chase the ball and, in the case of a few of the cheekier animals, even kick or push it on occasion with their trunks. (If you drop your stick, they'll also pick that up and hand it back to you.)

We played well, but the National Parks guys were on another level, passing the ball and hitting it nearly the length of the field. Our chances of upsetting them were sharply decreased when, early in the first chukka, with the Blue nursing a 5┬ľ3 lead (thanks to another five-goal handicap), Chip took a mallet to the temple. The match paused and he was untied from his elephant. When he hit the ground, his legs buckled and he looked to be on the verge of losing consciousness. He refused to leave the game, though, and played ferocious defense for the remainder of the match. We lost 6┬ľ5 but felt proud, despite not scoring for the second game in a row.

As we wobbled to the sideline, a tremendous lump poked out just to the left of Chip's eye socket. Jeff Bollerman, one of the New York Blue's bankers and the resident team wiseass, cracked, “You look like a Picasso.”

The Powerhouse came over to congratulate us. “I'm impressed,” he said. He'd taken a particular shine to Chip, proclaiming he “had a bright future in this sport.”

“Now,” he told us in the shadows of our resting elephants, “you need to score.”

In match three, we faced the British Gurkhas, representatives of the famous army regiment, who'd upset Chivas. If we could beat them, we'd end up in a three-team shootout with Chivas and the Gurkhas to see which squad would advance to the championship quaich (polo for “bracket”). The losers would go to the lower Olympic quaich, which has its own medal round.

The Gurkhas' star was Sarah Marshall, an intimidating and emphatic brunette in her early thirties. Marshall had two years of elephant polo under her belt and, being a woman, was allowed to use two hands on her mallet. Nonetheless, thanks to an unnecessary one-goal handicap, a couple of goals from Chip, and a nice strike from Bryan, probably the first Jew from Philly ever to wear a pith helmet, we won easily, 5┬ľ1.

The shootout was pathetic. His Grace the Duke had told us that it “will be one of the most nerve-racking moments of your year,” and he proved to be right. You get one chance to strike a ball from the top of the D; if you touch the ball at all, it counts. Prentice and Raj scored easily, and I got lucky, nicking the ball on my backswing but finishing the stroke quickly enough that the refs ignored it. It was our only point. Not a single Gurkha scored.

In the Olympic quaich semis, we drew the Indian Tigers, led by Jim Edwards's attractive thirty-something Indian girlfriend, Tia. My elephant, a smaller, more nimble fellow from group B, flat-out refused to play defense. “He's afraid of the children,” said the ref, translating for my mahout. Each day hundreds of uniformed children are bused in to watch, many of them from a school supported in part by the proceeds of the tournament, and they assemble on one end, which today happened to hold our goal.

It was a fortunate act of cowardice. I moved to forward and scored three times in front of a small contingent of Americans, including a batch of drunken, scraggly-bearded backpackers being led by wiseass Bollerman┬Śalso drunk┬Śin chants of “Yes, we can!”

At mid-match, A.V. Edwards, perhaps trying to motivate the Tigers, yelled, “Take your top off, Tia!” with a shake of his cane.

It didn't work. Chip added a pair of goals, and with the one-goal handicap we'd been awarded at the start, team Blue prevailed, 6┬ľ1. We were to face Kristjan Edwards's Tiger Tops team in the Olympic finals.

“NO SWEARING,” Stine Edwards said to her husband as we shared a ride to the pitch for the finals in the back of a Land Rover.

“No swearing, no swearing, no swearing,” said Kristjan, who tends to howl and holler and swear in abundance while playing, often at his wife/teammate, who in turn swears back. He fired up a cigarette and smiled as he rewrapped himself in a yellow pashmina. “No pressure┬Śthis is a practice for next year.” Dramatic pause. “But we've got to absolutely pummel the Blues.”

At the pitch, the Duke advised us to “put the fastest elephant on Kristjan.” Due to a unilateral rules change made the night before, after the better teams lobbied that the combination of overly generous handicaps and the clumping of elephants in the defense had made the situation untenable, we could now have only two elephants in either half of the field at a time. We'd start out with five goals, which seemed fair except that Kristjan had been playing like a man possessed since two opening losses and scored 14 times┬Ś14!┬Śin a blowout win over the Gurkhas in the semis.

We drew C elephants, the good group, and D proved to be even more sluggish than normal. Kristjan chose a little guy, who seemed scared of the bigger elephants and was painfully slow. Chip shut him down, and I had three full-field charges and nearly scored twice. At halftime we were still up 5┬ľ0. Then we switched elephants. Kristjan warned us not to trust the little one, but Chip, who had been playing exclusively on small animals, took it anyway. It was a bad choice. Kristjan poked holes in the defense and scored twice early. We buckled down, but a mistake led to a penalty shot, which Kristjan blasted between the poles: 5┬ľ3. His brother Tim, otherwise a non-factor, then hit what Kristjan would later call “the shot of a lifetime” and it was 5┬ľ4, a score that held into the final minute.

Maybe the most peculiar rule of elephant polo is that time cannot expire while the ball is in the D. Play continues until it is cleared or someone scores. As the time wound down, Kristjan dribbled the ball into our zone and I knocked it away, while Chip poked at him from just outside the D. The ball rattled around, and as the clock struck zero I relaxed, temporarily thinking the game over. But then I heard everyone on the sidelines screaming at me and scrambled to knock it away again, gaining just enough free space to wind up for a good backhand strike. It felt great, but it ricocheted off my elephant's foot and rolled right in front of Kristjan, who ripped one over the line to tie the game, 5┬ľ5.

In the sudden-death overtime, we threatened twice, but the Tiger Tops' Nepali defender, Ishwor Rana, burst from his position in the defense, dribbled the ball the length of the field, and scored. When Kristjan asked what had gotten into him, he responded, “I got tired of watching you guys not score.”

And so the upstart New York Blue lost in the finals, in heartbreaking fashion. The fact that we'd come in as the Jamaican bobsled team of elephant polo, and that five days prior we'd have been thrilled just to know we wouldn't embarrass ourselves, was lost on us.

A BBC reporter put a camera in front of Bill, who said, “Coming in, I thought the only thing going for us was grit. It turns out by the second game we had skill and strategy.”

He wiped sweat from his brow and smiled.

“We almost won.”