The news out of Nepal these past few days has been bleak. Avalanches and blizzards in a northern mountainous region of the country have claimed the lives of at least 26 people. According to some reports, as many as 100 people still may be missing. Most of the trekkers killed or currently unaccounted for were caught in a blizzard on Tuesday while walking the Annapurna Circuit, a popular trekking route roughly a hundred miles northwest of Kathmandu. October is prime trekking season in Nepal, when more than 100,000 international trekkers head into the country’s Himalayan foothills, hiking well-worn interconnected trails and eating and sleeping at the small hotels known locally as teahouses.

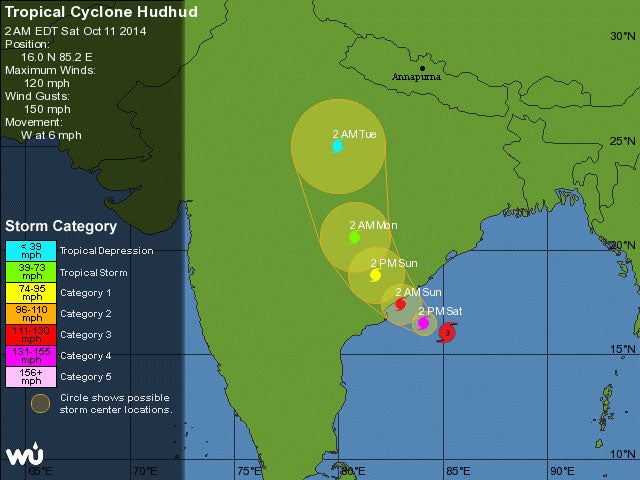

Normally, weather in the region is clear and calm this time of year. Earlier this week, however, an unusually strong storm system, the remnants of Cyclone Hudhud, which wreaked havoc on southeastern India a few days earlier, sent a powerful snowstorm rolling across the Himalayas. How so many people ended up in the middle of such a serious and well-documented storm isn’t entirely clear.

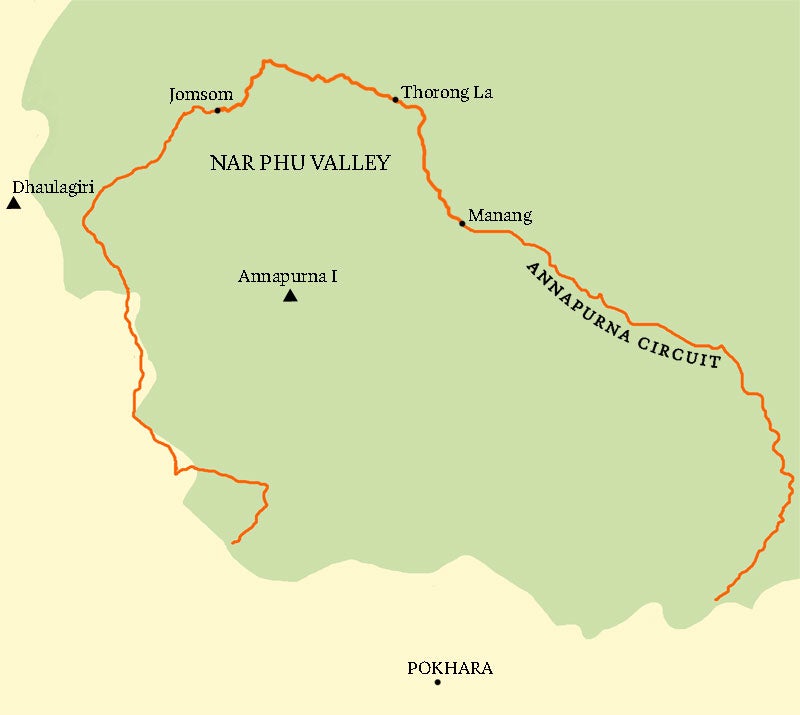

The bulk of casualties came in the area around Thorong La or Thorong Pass, the gateway to the Mustang region of Nepal and the high point of the Annapurna Circuit. At 17,769 feet, it’s 300 feet higher than Mount Everest Base Camp but still the lowest place to cross the mountains between the 8,000-meter Annapurna chain to the south and 6,000-meter Damodar group to the north. Thorong La connects the villages of Manang and Jomsom.

The entire Annapurna Circuit, the country’s classic destination trek, generally takes two to three weeks to complete. While a few trekkers were being guided by international outfitters, including , a travel agency based in Montreal, which on Wednesday confirmed that three women—two trekkers and one of its guides—were among those killed, most people prefer to travel more independently. It’s more common for trekkers to hire local help for the duration of the trip. Some hire full-service guides, while others opt to simply hire a porter, sometimes as young as 12 or 13, whose sole job it is to help carry gear. Generally, a porter will set off at a faster pace, leaving his clients to explore and navigate the mountainous trails on their own.

By the time trekkers reach the foot of the pass, Thorong Phedi, a tiny outpost with a few bare-bones lodges at 14,600 feet, most have been hiking for more than a week but haven’t been higher than 12,000 feet, the elevation of the Rocky Mountains. Many people head straight over the pass from Thorong Phedi, hoping to beat altitude sickness by getting over the pass and descending before symptoms set in. Others spend the night at Thorong Phedi High Camp, at 16,240 feet, to give their bodies an extra night to adapt to altitude before making the final push over the pass. But even with that extra night, trekkers are ascending Thorong La far quicker than they typically hike up to Everest Base Camp. The general rule of acclimatization above 10,000 feet is that you’re supposed to sleep only 1,000 feet higher than you slept the night before. Regardless of where trekkers start, heading up and over Thorong Pass in a day or two puts them at serious risk for altitude sickness. At a minimum, movements and judgement are impaired.

From Thorong Phedi High Camp, it’s still 1,500 vertical feet to the top of the pass. A small stone teashop marks the high point, but it’s little more than a rock hut where people can get out of the wind. The trail and surrounding hillsides are barren rock and scree with few landmarks even in fair weather. The other side of the pass is just as rugged. The closest village, home to the sacred holy site of Muktinath, is some seven miles and 5,000 vertical feet beyond the pass.

Even for someone in good shape, humping it over the pass is a big day, with most opting to start their hike well before dawn. On well-established routes like this, trekkers will typically send their overnight gear with porters, who go ahead of the group, walk fast, and arrive early at the next night’s lodge. Trekkers generally carry only food and water for the day plus a few extra layers and rain gear.

According to Michael Fagin, a popular meteorologist and lead forecaster at , “The brunt of the storm hit Annapurna Tuesday morning at around noon. When I see those storms heading toward the Himalayas, I tell my clients to go low. When you get those storms coming out of the Bay of Bengal and you get the orographic lift from the mountains, it’s something else.”

That “something else” would have hit the majority of trekkers just as they were reaching the higher slopes of the pass in an area where the trail is defined by lines of jumbled scree that’s packed and trampled by yaks. The route is clear and visible in fair weather, but with blowing snow accumulating by the foot, the trail disappears and the landscape offers few hints at the direction to go.

“A lot of it is cairned, but it would be pretty easy to lose your way if you didn’t have the long view of the trail,” says , a veteran Everest climber and regular visitor to the area. “It’s a big, expansive place with very few distinctive visual features if you’re in a whiteout.”

According to Fagin, radar data for the storm showed that the equivalent of seven inches of rain fell in some parts of the Himalayas. “You do the math for the snow,” he says. As a rough index, one inch of water is about 10 inches of snow. That means as much as six feet of snow likely fell in some places, though it would no doubt have been distributed unevenly by drifting.

[quote]Despite all the confusion about how many people may have been killed and how many are still missing, one thing that is clear is that even though many news reports have called the weather event a “freak snowstorm,” it was anything but.[/quote]

That kind of snowfall would reduce visibility to nearly zero. And on the steeper beginning and end sections of the trail, powdery spindrift avalanches would have begun shortly into the storm. Spindrift avalanches are the least threatening sort, except they can still sweep you off your feet and over whatever terrain or cliffs happen to be below you. They can also bury the trail, making forward progress like postholing through oatmeal.

For casual trekkers who thought they were heading to Nepal during the dry season, all of this would have presented itself very quickly with only bad options to choose from. Hunkering down near the top of the pass and waiting out the storm would have created a severe risk of hypothermia and altitude sickness. Descending is the best option, but only if you know where you’re going. Given the weather and visibility, many of the dead likely wandered off the trail or descended blindly and got lost, bogged down, and exhausted by drifting snow and froze to death that way.

One group of trekkers that included three Israelis was stranded with many others in the herders’ hut at the top of the pass. As they told a crowded room of reporters after being rescued, many of the other trekkers believed their lack of acclimatization gave them no option but to descend. As Israeli medical student Yakov Megreli , a dozen people stayed huddled in the shack above 17,000 feet, taking their chances with altitude sickness, while 40 to 50 others followed the proprietor of the teashop into the storm in an attempt to descend to Muktinath. Their whereabouts remain unclear.

After the storm, cellphone reception was knocked out in much of the region, making it difficult to confirm who made it out and who didn’t, although rescue teams have managed to reach many of the trekkers pinned down by the bad weather. The Trekking Agencies’ Association of Nepal (TAAN) has reported that it rescued 77 trekkers from different parts of Manang District on Thursday, including 29 Nepalis, 17 Israelis, five Indonesians, 10 Germans, five Spaniards, four Indians, three Canadians, two Russians, and two Poles. A complete list of the individuals rescued can be found on TAAN’s . Another Facebook page, the , has been set up for friends and relatives to share information with one another.

In addition to the deaths on the Annapurna Circuit, several yak herders perished in the area, and many locals are among the missing. More Nepalis than usual were out on the trails ahead of several local festivals. At least two avalanches in the region have also claimed lives. A slide on Wednesday killed eight people in the Nar Phu Valley, to the north, and another avalanche reportedly killed five climbers who were hunkered down at the base camp of Dhaulagiri, farther to the west. According to Gyanedra Shrestha, of Nepal’s mountaineering department, two Slovaks and three Nepalese guides were killed while preparing to climb the 26,800-foot peak, the world’s seventh tallest.

Despite all the confusion about how many people may have been killed and how many are still missing, one thing that is clear is that even though many news reports, including the Times, have called the weather event a “freak snowstorm,” it was anything but. Cyclone Hudhud was a Category 4 hurricane with a storm track that was predicted by multiple weather services, including NOAA.

“I had several clients doing climbs, and I notified them a week to 10 days ago,” says Fagin. “People were saying that the storm was unusual, but it’s not out of the ordinary.”

“They’re calling it freakish, but it’s not uncommon, and its not unheralded,” says Athans, noting that he’s seen the monsoon last later and later into the fall over the past decade. “We still see these monsoonal burps coming up the valley in October now.”

That a hurricane in the Bay of Bengal would produce a blizzard over much of the Himalayas was a certainty at least two days in advance. And as crazy as it sounds, the Nepalese Himalayas have surprisingly good cell service and Internet. Most of the young trekkers traversing the circuit still find time to check their email and update their Facebook pages. That so many of them blundered into a Category 4 hurricane–spawned blizzard means that either the information didn’t reach them or nobody heeded the warnings. Unlike this spring’s Everest avalanche that killed 16 Sherpas, this was a major meteorological event with plenty of lead time.

There’s no excuse for so many trekkers getting caught by surprise. Maybe they didn’t get the information they needed. Or maybe strong warnings went unheeded. Either way, 26 lives should not have been lost.