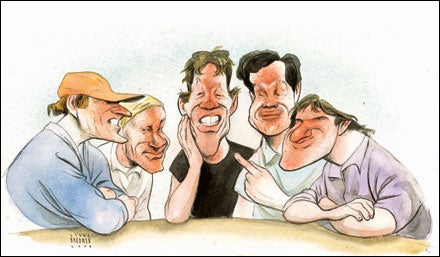

The panel:

Mount

Mount Everest, the world's highest peak.

Mount Everest, the world's highest peak.NEAL BIEDLEMAN, 46, Aspen Colorado. One Everest summit. Beidleman worked as a guide on Scott Fischer's 1996 Mountain Madness expedition on Everest.

GUY COTTER, 43, Lake Wanaka, New Zealand. Three Everest summits. Owner of ���ϳԹ��� Consultants, the New Zealand-based guiding company formerly owned by his friend Rob Hall.

DAVE HAHN, 44, Taos, New Mexico. Seven Everest summits. A longtime Everest guide who has been on 14 expeditions to 8,000-meter peaks.

ED VIESTURS, 47, Seattle, Washington. Six Everest summits. The only American to climb all 14 of the world's 8,000-meter peaks without supplemental oxygen, Viesturs helped carry out rescues during the '96 season.

JENKINS Ok, first of all, welcome to all you guys. I've spoken to each of you before, and I really appreciate what you're doing. This roundtable thing will probably provide some kind of a foundation for future discussions about what Everest is like right now, and what it will be like in the future that's what I'm hoping for. For this roundtable, what I'd like you to do is first go around the roundtable, doesn't really matter who starts, Ed you were the first guy on, maybe we can start with you. Go Ed, Guy, Dave, Neil, give your name, age, your occupation and the number of times you've been on Everest. Alright, let's just start. Ed, you can start and we'll get going.

VIESTURS: My name's Ed Viesturs, I live just outside Seattle, Washington. I'm 46 years old. I've been on ten Everest expeditions and I've been six times on the summit.

JENKINS: Great, ok Guy, go ahead.

COTTER: My name's Guy Cotter, I live in New Zealand (As the transcriber will be able to get by my accent) I'm 43 years old, I've been on Everest four times mountaineering, five times total….summitted three.

JENKINS: Alright, Dave, lay it on us.

HAHN: My name's Dave Hahn, I'm from Taos, New Mexico. I'm 44 years old, I've been on Everest 11 times, and got up seven times.

JENKINS: Neil, Your turn.

BIEDLEMAN: My name's Neil Beidleman, I'm from Aspen Colorado. I guess I'm the rookie here, I've been to Everest once and summitted once.

JENKINS: Ha ha, nice clean record. Well, we're all of very similar ages, which is kind of neat. We've all spent an enormous time over the last 25 years in the mountains, so this should be fun.

What I'm hoping is that everybody will feel free to just throw out thoughts and ideas as I ask questions and I'll probably direct some questions to specific individuals since I've spoken to all of you and know some of you have specific thoughts, but ideally I wanted to have all of this in one room after about a six-pack each, and really talk about this stuff but that's not happening so it can be as informal as we can make it just by being on the phone.

I'm just gonna dive in here and this doesn't have to follow the protocol that I created, these are just questions I've come up with after talking with you guys and also talking with folks at ���ϳԹ��� .

So, what we're doing, why we're all together is to talk more specifically about kind of the commercialization of Everest, what that means, and at the end I hope we can move forward and talk not about the past or even the present but about what Everest could look like or perhaps even should look like in the next five, ten, 20 years.

Alright, first question. Dave, I'd like you to give a crack at this, just to get started. What does the commercialization of Everest really mean on the mountain? If you could give us a picture of what's happening on the two commercial routes on the mountain, the north col and the south col, just for starters what does it look like?

HAHN: Well, I think that the commercialization has actually had a stabilizing effect with things on the south side. It is normally the same operators working year in and year out, with a little bit of variation here and there, but we've got pretty good at working with each other on the south side, we generally know each other and there's pretty good cooperation between our Sherpa teams.

A benefit of commercialization is that our sirdars and serdars Sherpas have all found steady employment as teams rather than being a random sampling every year, and that's been positive. On the north side, that stabilizing hasn't really happened so much yet. There are plenty of commercial outfits working on the north side, but less steadily. There are a couple of players who've been coming back consistently to the north side but there's been a lot more start-up commercial teams or one-time-only commercial teams that venture to the north side. I see it in terms of stability, and there's some pretty stable outfits out there but there's a lot that, yeah, that are lot “less stable” let's put it that way.

JENKINS: Guy, why don't you jump in here? Guy and David both just returned from Everest, so why don't you give us maybe a picture. How crowded is it on these routes, Guy? How's the climbing? What's the fixed-line situation? The camp situation? I'm just trying to give a picture to our readers of what's actually there.

COTTER: Fair enough. I would say from a crowded perspective I can't comment on the north side because I haven't been over there but I would say, in terms of the south side, we saw our biggest crowding, I think it was around '93, and that was when the Nepalese government decided to increase the peak fees from around $10,000 US for a permit to around $70,000 US the following year, so it seems around '93 it was a very, very busy time.

Since then, I don't think we've seen as many people on the mountain. It's hard to speak to, but you might be looking, in a year like this year, at 17 different teams with seven to-12 people on each permit. That could correspond to at least 300 people in base camp. And I don't know what the final stats were, but I think somewhere over 400 people summitting from both sides, and up to half of those coming from the south side this year.

But how crowded that really seems on the mountain is kind of dependent on certain factors, such as the weather throughout the season. If you've got good weather, people kind of spread out on the mountain. If you've got a limited number of summit days, (there are only a couple of days that people are able to summit) then it obviously does feel very crowded when all the teams are trying to summit through a short window period.

Overall on the mountain, it can seem relatively busy on certain days, but years like this one with a reasonable amount of good weather, people spread out on the mountain and it does not seem that crowded.

How it all works on the mountain with fixed-ropes, camps, and everything like that, is that as Dave alluded to is that with teams coming back year after year things seem very well organized. Everyone has a good system of doing things. We've all worked together before, we all communicate about how things are going to be gotten done, and therefore the whole process of putting in ropes and campsites seems to flow quite well.

JENKINS: Ed, how does this sound to you? Neil, as well? Neil, you were there in '96, we all know that. Ed, you've been there many times. How has it all changed since '96. What are the changes you see?

VIESTURS: Well, I think Dave is correct that a lot of the consistent players tend to be on the south side and there are a few that hang out on the north side, but the north side is getting more and more popular simply because, I think, that the fees are less on the Chinese side so people are going to take advantage of that.

But also, on the south side, other than the (what I think) legitimate players, and guide service and outfitters, there are a few people that trickle in with the label of “organized expedition” or “guide service” and really kind of get away with things that we scratch our heads at. And I don't know if that happened this year, if you've seen some of that, but two years ago, we saw a few of those people up there and, um .

JENKINS: What are you talking about Ed, getting with things that you look at askance at, or think might not be safe? Give me an example.

VIESTURS: The way they're guiding, and the types, and level of ability that their clients have. And the level and ability of the person that is actually guiding and leading. That person often has no right to be there themselves, let alone leading a person or a group of people. If something goes wrong, he can't handle it, or they can't handle it. So here we go with a people that Guy said as well they got their act together, they're acting cohesively with other groups that communicate and then there's these other groups that kind of “squeeze up, squeeze down.”

JENKINS: This might be a good opportunity for anyone to jump in and kind of start outlining the spectrum of guiding on Everest. I've spoken to all of you about this, and everyone wanted to say something because it seems as if, Ed you said something like that you kind of get what you pay for in terms of guiding, .And I think everyone knows that climbing Everest costs money, this is nothing new, and that camp costs a lot of money, but what I don't think people don't understand is what that money is about: what that money provides for you, what kind of services are happening. I was hoping that someone would jump in and kind of differentiate what a guided trip means, according to the money you spend. .20K, 40K or 60K, what's really happening? I think that many of our readers have no idea.

HAHN: Well, you know one of the things I think happened with the '96 publicity on the mountain, was that people started to be aware of the amounts of money that are involved in Everest climbing. But I think that they only got part of the story. The story back then seemed to focus on the fact that people were paying $65,000 and the implication was that they were buying their way up Everest with that kind of money.

But, that's an impression in a lot of people's heads that that money went straight into somebody's bank account and it doesn't for an Everest expedition. No, Everest climbing is very expensive, by being on the other side of the planet and all the logistics involved, a responsible trip to Everest can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. To employ good Sherpas, a strong team for the length of the trip, to get oxygen in place, to have some kind of back-up, maybe some access to medical care, etc. etc.

So it is a very expensive enterprise, and when people look to do it on the cheap we all know of advertisements, and people taking them up on it for $6,000, $10,000, $20,000 per person, and that's ok if all you need is the permit and the barest framework. If you're an experienced climber maybe that's all you need.

The worry for all of us is to see somebody less able to take advantage of that cheapest trip, yeah, and actually going for the absolute cheapest trip then sure enough, there are no resources.

As an upward-end, people are still citing $20,000-$60,000, but you can tailor a trip to your needs and perhaps it can be more expensive than that. If you have less experience, and want to stack the deck in your favor, have more safety, it can go higher than that.

JENKINS: Guy, do you also want to pitch it here? Because I remember our conversations two years ago were fairly lengthy about this issue, and I think it's important for people to understand kind of what they're getting in the range of services on Everest.

COTTER: Yup, for sure. It's obviously something that all of us involved in the discussion of sourcing the different levels of service available, and interestingly enough, the guided expeditions the more expensive ones are more expensive because you're bringing in western guides Y you're paying them western guide fees. It is very difficult to fill expeditions like that. there are only a certain number of us who can operate guided trips and they're the ones obviously with all the services in place.

You can have a guided trip, which can be a ratio of one guide to three people. Tthe likes of what we offer and I think what Alpine Ascents offers is similar compared to what can be offered as a guided trip, that is one person who calls himself a guide whose in a permit on the north side with up to 29 people on one permit.

So therefore, the definition of “guided” is a little bit blurry, but the real definition of guided is a good guide-to-climber ratio, and therefore they are gonna be more expensive expeditions.

Then you've got different levels, you've got a commercially-led expedition, or a commercially-organized expedition, which is one which has a guide perhaps running the expeditions, but all the members are independent climbers. There's a lot of expeditions offering that level of service, and they are sort of in the $40,000 range. And then you've got the bottom level the bottom-feeders that are out there that are offering the real cheap-o trip, which really has not much to offer at all, and what has really been of concern. I believe, in the last few years is that there's been some Nepales trekking agencies that have seen that this can really be a cash cow, so what they're doing is offering trips at the bottom-end, which is services-only, so people get a permit.

They get perhaps a tent and often they can get some additional services on top of that, such as oxygen, maybe some food even, and get to go on these trips. And it's interesting to see the proliferation of these types of bottom-rung trips because there's a lot more of these than there are guided groups at the more expensive end.

And these are the likes of the trips that David Sharpe was on, for instance. And as Dave mentioned, they don't have any back-ups or services, these are just selling seats, and they're selling them often to anyone who's prepared to come along and throw some money down.

JENKINS: Let's talk about back-up, and anyone can jump in here. This is something you've all brought up quite a bit: if something goes wrong, you need back-up. What does this really mean? Probably, what you're saying is that it's costly; its costly to have guides that are capable, it's costly to have Sherpas that are ready to go. Is that what back-up is?

COTTER: Who are you asking?

JENKINS: I'm asking…you! Haha…why not?

COTTER: Ok, alright. Yeah, all that stuff costs money, and every additional person you put on the expedition, it all costs a whole lot more, and to be “responsible” (as Dave used that word earlier on) means paying for a lot of services that you probably aren't going to use, so you have switches in place. You have extra oxygen, you have medical supplies, you might have a doctor. And so on and so on.

COTTER: Yup, radios, Sat phones, the whole bit. And this can actually only be accumulated over time, so those operators that have been around, offering services for a long time have built up a good system for dealing with it. And each year we tend to spend more and more and more on tweaking things and making them better, and this is one area where the commercialization, the fact that we're returning, has actually helped a lot.

I think that we who do this want to be able to sleep at night or some of us do not that I'm sleeping now, (laughs) but, we want to be able to sleep at night. We want to be able to know so that our expeditions can run and if something goes wrong we can do whatever we can to make it right. And this is often happening, we're actually working with other teams that don't have the back-up to help them, because we often find ourselves in the situation where we are getting involved in helping people on the cheap expeditions out, fixing up their problems.

JENKINS: Ed, I want you to jump in here. Having guided there yourself a lot, because of the money involved, is there a certain amount of pressure from the clients on the guides to get them to the top, and does this influence your decision-making as a guide? And Neil, I want you to jump in here at a point too, because I know on the '96 trip, there's been a lot of questions about whether money influenced decisions.

VIESTURS: Well, I would say in general, “perhaps” but for me, I would say that the fact these folks are paying a lot of money doesn't come into play.

I think I figured it out that as Dave said, it does cost a lot of money to run an Everest expedition and I think the perception as well, since '96, people read about “hey you buy a ticket to the top.” And for that expensive ticket, “you better damn well sure get me to the top” That's the perception from the client's point of view fairly often.

But I think most of the guides at least the ones that are thinking straight and running legitimate operations know better than that. They say “listen, we know that this costs a lot, but the rules on Everest are going to be the same as on any other mountain that I guide on, if not more stringent.”

But you can see that perhaps there is a little bit of added pressure to perform, and for that investment of time and money to maybe help these people get to the summit, maybe nurture them high onto the mountain when in other cases you might be saying, “listen, I don't think you're capable of going further.”

So I think there might be a little bit of that pressure that's going on. And also the fact that if you succeed this year, with that team and that company name, that could be your calling card to sign up people for the next season.

Then there are all these teams up there and maybe one is pushing ahead, and then another one maybe is deliberating on whether or not to go up or what to do, and maybe they're getting pulled along as well, while when they're on their own they may be making different decisions. So there's a lot of things coming into play when people are making decisions up there when on the mountain.

BIEDLEMAN: Yeah, I'll jump in there as well.

JENKINS: Please

BIEDLEMAN: Yeah, I think that's sorry, go ahead Mark.

JENKINS: No, I was going to say “go for it, Neil.”

BIEDLEMAN: Yeah, I think that's well said and a very good perception. Certainly back in '96 I think, there was some background pressure on Scott to perform well. I'm not so sure you could call it “direct competition” with Rob Hall, but certainly there is pressure in Scott's mind to provide good services, to make good decisions, to try to get people up the mountain.

I think that Scott clearly knew that if Rob succeeded in a fabulous way and we were sitting at base camp waiting for something else, that might be the end of his guiding up at Everest.

So I think it's in the back of people's minds. Maybe not as much now, just because of what happened in '96, but prior to that time, there really hadn't been any major tragedies or episodes with guided trips at least not publicized so, yeah, I think Scott felt the pressure.

JENKINS: I want to throw something out here: I've always seen it as the responsibility of a guide, part of what you're paying your guide for, is to make the very difficult decisions, kind of like a general has to make very difficult decisions about the life and deaths of his troops, same thing with a guide. And that, in fact, a guide is there to make a decision about whether you are capable of continuing on. Is that not one of the toughest parts of being a guide?

HAHN: You bet, you bet. But I think it's easy for the public to have a simplified view of that as if it all happens on summit day. And, of course in the real Everest situation, you're climbing together for a month and a half, two months before that day, and so that kind of decision-making and helping someone know whether they're ready for the thing or not, can or probably should come long before that summit day.

That's not to say there wouldn't be pressures on you that, against your better judgment, somebody ends up on a summit day that shouldn't be there, and maybe you have that tough decision to make, 100, 200 feet from the top, that really sets everything up to the boiling point.

But you know, to add a little to what we were just saying, these pressures aren't just on Everest, they're on all of the mountains we work on. It costs a heck of a lot for get people down to Antarctica. They want summits. But if you're in this for the long run, it comes down to your own fingers and toes, and yeah there is financial pressure, but to my knowledge, nobody I know is getting rich off of this business.

If you take a billionaire up, it's not like he's going to give you a couple of million for getting him up! [Laughs]. Not to me at least.

HAHN: (Laughing), It's still just making a living. And yeah, that pressure can be immense, but maybe not the way people seem to think it is.

VIESTURS: If I could make one comment. A lot of the people especially in the higher-end expeditions where the people are paying a lot, and paying for the quality services, and the organization of those more expensive trips as Guy said, there's not that many people who can really afford those, and the ones that have enough money to afford it are quite often very successful, very influential in whatever field of business that they're in.

Quite often, they're used to getting they're way. That can be difficult for them when someone else, rather than them, is calling the shots. And yes, even though they do sign up for a trip and at the beginning understand that they're going to get leadership from someone else, when it comes to being on the mountain and someone's telling them “no,” they're often not used to hearing that word.

They're like “what do you mean no? This is what I want, and this is what I paid for.” So sometimes, as a guide, when you have to make those tough decisions, you have not only be a guide, you have to almost be a psychologist and help these people slowly understand that they may not be capable.

So you don't come up and blindside them and say “listen, that's the end of the trip.” The whole idea is to slowly let them know along the way, so hopefully they convince themselves before you have to come up and tell them. And of course there are some people that don't quite get it and you've got to then come up to them and literally just say “that's it.” Hopefully for the most part, they'll agree, but then there are a few that are just like, “what do you mean? I don't understand.”

So part of the thing that a guide needs to do is help these people understand their capabilities when they're climbing.

JENKINS: Dave, Guy, and Ed and Neil as well too, have you all had to be in this situation and tell people to turn around?

VIESTURS: I've done it. And I've always had the attitude that, you know, I don't want to be taking somebody up high on the mountain that is a liability not only to themselves, but to me.

When it gets really tough up there, you could risk your life having to bring somebody down, so if there's any indication lower on the mountain that these people aren't performing I mean, that's the whole idea of going to the mountains with these people, it's not like it's a guarantee that they're going to go to the top. It's a chance to try to see how they perform. And they should understand that climbing is not just going to the top, but it's the whole process and the whole journey, and to just experience and maybe learn along the way as well.

And if things go well, then maybe yeah, we get to go to the summit.

HAHN: . I'd say it's a constant part of guiding. I've turned guided folks 200, 250 feet from the top of Everest. And luckily the weather turned awful and you know, it looked like the right thing to do, but the weather might have turned for the better and we had still turned around short at the top.

It's got to be a huge part of the job, and on any mountain you're always trying to keep track of just that level of what's right for this person to be pushing in this dangerous environment, and when have we gone too far.

One of the reasons that none of us that you're speaking to this morning likes to point fingers too much (like after a '96 or something like that) is that we all know we could be in similar situations and be just a little bit on the wrong side of the right thing to do.

The same tragedies could happen to us if we keep working in that dangerous environment and working up near that limit. I mean, Rob Hall certainly knew the game, Scott Fisher knew the game, but yeah, those pressures are real, they're always there, and they can catch us.

JENKINS: Well, here's a question that came from one of ���ϳԹ���'s editors: What is the guide's responsibility to this client and to himself in extreme situations? I think we're probably talking here in the death zone, above 8,000 meters, in a difficult situation. What are the guide's responsibilities to his client and to himself? Anybody can answer that.

COTTER: Well, I might jump in the air and say that obviously our responsibilities are to try and get ourselves and the people we're with back safely from an attempt. And whether the summit is involved or not, is kind of irrelevant.

For those of us who are here talking today, the reason we're talking is because we are capable of making that call, of being able to say “ok, this is the place to turn around, we want to get you back down first and foremost.”

I think that to be in this game and to be a successful mountain guide, that's got to be your first priority. And it's quite simple really. We all know that standing on top of a mountain is really just reaching a geographical high point, nothing more. But we've made it seem a lot more to us, and it means a lot to our clients and people in general, especially Mount Everest.

But at the end of the day, we all want to go back and tell people about our experiences, so our motivation is to get back down. And this brings us back to the question we were just discussing. In my view, a big part of what our role on the mountain is instead of just being there to turn people around to coach people to succeed which is a process that often happens throughout an expedition.

So we are with people for a long time, and a lot of what we can provide to our clients is our skills and experience and help a lot of our people get through struggles they might have acclimatizing and just working at how to get up this huge mountain. And again, that is part of what defines the difference between the $65,000 expedition and the $20,000 or the $15,000 expedition is having guides with the experience, with the will to see the clients succeed, work through a lot of their issues, so that they can succeed on the mountain and not give themselves trouble on summit day when they find themselves strung out, in the middle of nowhere, running out of gas and not knowing how to deal with things.

I think for all successful guides, one of the personal traits we have to have is our own will to succeed. We don't get clients up these mountains by being blasé about it. We really have to want to succeed ourselves, and the decision-making processes we go through are definitely driven by our own will.

We all want to get up the mountain when we're there and this personal drive pulls as well. But we also want to get back down, and those of us who have been around for a few years have proved that we can most of the time make that decision pretty well, whereas some of the teams that will go to Everest, some of these first-timers or one-time-only guided trips, you know, their decision-making is kind of blurred because of personal ambition that hasn't been tempered by time.

JENKINS: This kind of moves us on to the next question and that's kind of the biggest question of all in some ways, and that is, can Everest be guided? Now, I think now we're seeing some differentiation between different types of commercial trips, and clearly when the weather is good and you have a good system involved, Everest can go fairly well. Guy, I think you told me you just came back and your team put 28 people on the summit, no frostbite, no death, no nothing isn't that what you said?

COTTER: Yup, that's what I said. And that was over two summit days. Yes, it did go well for us and it went well for a lot of people. It is certainly a lot easier when you do get good weather; that means that there is less to have to deal with. Not only for our own team, but dealing with other people and their issues that we often get caught up in.

You know, this palaver over what happened on the north side this year, this sort of stuff does happen every year all the time, it's just that for some reason this time the media has gotten a hold of it and is running with it.

JENKINS: Well let me ask all of you something here: if weather's good, if you have a system in place that's operating, if you've got as you, Ed, point out a lot the cohesiveness of a team, it seems guiding on Everest works. But what if things break down somewhere along the way? And, being a climber myself, I know how easily this can happen. The weather can move in quickly, somebody can suddenly trip on a crampon strap you have any number of incidences that are just common in mountaineering. What if they happen up high? Is it really possible for guides to rescue in the death zone, above 8,000 meters? Anybody can jump in here.

VIESTURS: I think that it is possible. Guy and I know it can be done, we've done it before. But this is with a cohesive team-where you have a team that can communicate, whether its radio or verbally. And where the guides and the leaders have the training and the experience and the strength at those altitudes to start not only initiating something like a rescue, but also to perform it.

Where you trickle down to the expeditions or the services where maybe they've thrown together a team of guides, and they've not been to those altitudes, when something goes wrong up there, those people are barely able to do what they're supposed to do for themselves, let alone initiating a rescue. So it comes to the point where it's up to the experience and the strength as well of whoever is leading these trips when something goes wrong up high, because it gets more difficult to think about what to do, and then also to perform.

When you have these commercially-guided, loose organization-type trips when people are kind of just up there on their own, quite often sadly, it's the Sherpa that have been assigned to be the quote-un-quote “guides.” There's no one else other than the Sherpa from that team to watch over the people who are climbing, even though they think they don't need assistance when trouble comes, the Sherpa then have to take the brunt of the responsibility. And quite often, they don't have the training or the knowledge to do that. But quite often as well, they perform heroically but get very little recognition for that.

HAHN: I agree. I think that a huge burden of rescues these days goes on the Serpas, and the mainstream media stuff that I was seeing after getting off the mountain this year talked about this team rescuing that team, but we all know that the people doing the real rescue work, the work people doing the work are the Sherpas. And yeah, the scariest situation as Ed was pointing out there is the lone Sherpa on a team where the western climbers have cut corners all the way and it comes down to that Sherpa working all by himself up there with somebody who has pushed a little too far.

And yeah, you hate to see that burden come on that guy who is a farmer the rest of the year and is trying to support a family. One of the reasons I'd choose to guide on the south side rather than the north side, is that having tried to drag people down the upper north ridge and having tried to drag people down the upper south side, you can drag somebody easier on the south side!

You get to the south summit, and you can haul somebody down-and that's verrry difficult. I'm not saying it can't be done-we've had some success with rushing people off the northeast ridge but I think you can get rid of altitude a lot quicker on the south side, and once you hit the south summit with the balcony, I think that makes a big difference.But yeah, I feel pretty strongly that Everest can be guided. Just as the Matterhorn can be guided. But there will always be accidents, there will always be deaths. It's dangerous.Everest can be guided, but not easily, not casually, and there are always going to be hazards to it.

JENKINS: Neil, I'd like you to say something here if you would, because you were intimately involved in the '96 tragedy as a rescuer. And I think what I'm hearing, it seems to me that if you can affect a rescue on a mountain then there's some legitimacy to guiding it. If you can't ever affect a rescue in a mountaineering situation, then the question of guiding comes up, because that's when the shit hits the fan. Neil, give me your perspective here.

BIEDLEMAN: Well, in our situation as you know, and these guys…Dave, I don't think you were there but certainly Ed and Guy were there we had more than just a single person that got in trouble. It was more problematic for the whole group, so the focus wasn't at least during the summit bit, trying to get just one person off the mountain, it was the rescue of the expedition in a lot ways.

I was able to help some people down from the south summit actually a little bit above there as well, to the south summit, but I wasn't put in the position where I had to grab somebody who was absolutely motionless and incapable of doing anything and get them the entire way down myself.

Once I was able to get some people stood up or dragging a little bit, and then moving, they were able to help themselves slightly. But it was just myself at that time pretty much, doing that. And I think if you can catch the people early then you can certainly do a tremendous amount to help them and get their motivation and their confidence going so they know that they can proceed and that they don't give up.

Later in our expedition, as people we're not able to get off the mountain up higher and things became more dire, then you're more in a situation where you're talking about where you have to evacuate or rescue somebody who is completely incapable of doing anything, and that becomes much, much harder for us.

COTTER: As he alluded to earlier on, we affected a rescue in 1995 of a practically unconscious person from the south summit. And essentially it is almost easier, as Dave says, on the south side to drag someone down when you're south summit or below.

It's possibly something prospective clients should ask guides, rather than how many times they've been to the summit, is “how high have you dragged somebody off the mountain from before?” (Laughing)

It's only when things go wrong that you see what you're paying for on the expedition. The response that people have, the way that the guides and the Sherpas as a team deal with an issue, is what defines the difference between one team and another, quite often.

And to rely just on Sherpas-and especially in the situation that's been discussed, of one sherpa, often with two or three clients when things go wrong it puts a lot of the onus on them to have to do the rescue. But traditionally, Sherpas aren't trained in rescue techniques and also from the point of view that often the Sherpas are reticent to have anything to do with sick people or dying people. Their natural tendency for a lot of them is to run away as quickly as possible and that's partly a cultural thing and that's changing over time but that's one of the things that you do see when things start to go very wrong, is that often they don't want to be there at all. That's where that western leadership working with Sherpas often does make for better rescues, and you've actually got the combination of skills to put things back together. You can only see that side, (of the strength of the team) when things do go wrong and when people are prepared.

JENKINS: Ed, I'd like you to say just a couple words on cohesiveness. We had a lengthy discussion on it, and you seemed to think that that was at the core of a functioning team. I think that readers would like to know about it.

VIESTURS: Well yeah, I mean traditionally, when you go on an expedition to a mountain, the very altruistic way that people did it was we'd join together, whether it was ten or 12 or 15 of us. We work together, we know each other, we like each other, and ultimately the goal was to maybe get two of those people to the summit.

I mean that was the way I started reading about the history of these large-scale expeditions. Now, there is less cohesiveness because when people sign up for an organized expedition, when they show up in Kathmandu, they really haven't met each other and then all of a sudden they're together on one of these climbs.

I know that when I try to run one of these trips, I try to get the people involved with each other and to help each other and to start working as a team. But as you get higher and get closer and closer to the summit, people tend to think a little bit more selfishly.

They've gotten themselves into that position, they kind of want to take care of themselves, they've paid a lot of money and then here we are getting close to the summit so their extra energy, rather than being spread out through the team, kind of gets contained within themselves because they want to get themselves to the top.

Then, if something were to go wrong not only within their team but perhaps with somebody that's not even part of their team, then they really have to start thinking hard, really “what do I have to do to help that other person? Because ultimately it is going to compromise what I'm trying to do.” So there's a bit of a difference now in the way the term “team” is put together, and how these people are interacting and how they're thinking about the group as a whole.

BIEDLEMAN: Yeah, it's so true Ed. When you get a group together

My thought was and I certainly saw this on our trip, and have seen it in other guided trips to other places that from a client's perspective, they don't necessarily have the reasons to care so much about other people's problems. They have just met these people, there's not this cohesiveness there. And if they're good people, and good-natured human beings and all that, they care because there are other people there, but there's not a longstanding friendship or a relationship that goes back, as a lot of climbers have who have been climbing together have, and again as Ed alluded to.

But the other perspective, looking down, from a guide's perspective, it's his or her responsibility to look after all the needs of not only himself and his team but of the clients.

So there's not a complete reciprocity there that used to be there when teams were formed months or years before a trip took off and everybody really knew each other and even trained together and went out and did some climbs together beforehand. So it's a different kind of thing, and the burden on guides now, and certainly these other guides can talk to it really is well, is that it's really hard to form a team where the team members know and quickly learn that their responsibilities are more than just for themselves. It's hard to do.

HAHN: I'd agree with that and certainly with what Ed and Guy we're saying about cohesiveness, and the lack of it being a problem. The way I would address that is, you know, make a more manageable situation. Have fewer climbers on the trip, fewer novice climbers, fewer customers, and add resources add stronger Sherpas, more Sherpas, more experienced. Add more western guides. Add to the cost!

JENKINS: Basically Dave, what you're saying is you can increase cohesiveness which, according to Ed and Guy, increases safety and perhaps success. But that means reducing client-to-guide ratio, which means increasing the cost. Is that an accurate perception?

HAHN: Yeah, but I don't own a guide service, and I don't have to convince clients to come on the telephone, so I can say that! And certainly there is a limit there, but that is my response to a lot of that stuff make it cost more. Personally, I don't have much sympathy for somebody that wants to be there on the cheap, somebody that wants to save a little money on their boots, their gloves, their guide. I don't really want to be there with those folks.

JENKINS: Why is that David? Are you saying that because they want to go on the cheap, they're putting themselves at greater risk and therefore putting you at greater risk? What do you mean by “you don't really have sympathy” or “you don't want to be with them necessarily?”

HAHN: I guess it comes down to that after 11 Everest expeditions, I'm still pretty scared of Everest. I think it's guidable, I like working on the mountain, but looking up a the thing at the beginning of a trip still scares me, and worrying about what can go wrong well that's a constant part of these trips for me.

So I guess I want to be with people that are a little worried as well and have either made up for that worry by getting themselves in incredibly good shape or gathering up a ton of good experience, or at very least having devoted the financial resources to put together a trip that has a fighting chance. And yeah, we're talking about lack of cohesiveness, well, with ten or 15 clients, yeah there's more chance of that lack of cohesiveness when people don't know each other.

If you can reduce those numbers a little bit, perhaps there's a better chance of achieving that cohesiveness, and getting a real “team feel” and an obligation to each other. I don't know, it's a possibility.

JENKINS: I think this is a perfect segway into my next question. I know we're not moving fast and I hope that that's okay with you guys but it's great stuff, and I'm hoping the magazine uses it all! Ok, I think you guys have done a fairly good job of saying why you believe that Everest can be guided. Now the question is, should the guiding services and the guides be regulated?

Dave, you brought up the issue of the Matterhorn. Yeah, there have been over 500 deaths on the Matterhorn and it's still guided but it's regulated. Same with Rainier. Same with Denali. You guys are all familiar with this. Most of those mountains many of the big, famous mountains you have to be a concessionaire, and that concessionaire has to have passed a skill test and safety and rescue tests, and they are very, very competent. I just came back from Alaska and was involved in the search for Sue Nott , and that team up there is unbelievable that ranger team and the concessionaires who work that mountain are also unbelievable. And that's not the case necessarily I think is what you're saying, on Everest. Now should there be some sort of guide licensing for Everest? And if there should be, could it be implemented?

COTTER: Well, I might jump in there, and say that I personally think it would be very difficult to regulate guiding on Everest, the reason being that the Nepalese rely heavily on the income from Everest especially for part of their GDP.

I mean, we do bring in a lot of money to that country on expeditions and they're not going to do anything to reduce that. I think that some of the expeditions that are occurring over there especially the cheap commercial expeditions that are popping up are, actually Nepalese trekking agencies running a lot of these expeditions. So therefore, these trekking agencies have a lot of political clout and support and it's going to be very difficult for the Nepalese government to turn around to these people and say “oh no, you've got to be regulated by some Western standards.”

They're not going to like that at all. It'd be like us imposing our standards on them. Last time this sort of discussion came up, Sir Edmund Hilary mentioned that he thought the mountain should be closed, and at that stage the price for going to the mountain went up 700 percent.

JENKINS: What's this the peak fee? Guy, the peak fee jumped from $10,000 to what it currently is at $70,000? And you're indicating that that this is because people started talking about regulating guiding on Everest?

COTTER: Yes, and so therefore, often the response to these calls for regulation lead to something we don't really want. You brought up Denali, which is one of the most highly-regulated mountains in the world, you know, because the park service only gives a certain number of concessions and is very much involved in how all that works. I think that from the outside looking in, Denali doesn't really work as well as it could because it's over-regulated by a government body that isn't involved in the actual guiding itself.

So I think that that, applied to Asia and Everest would not work at all well. I think, again, it's a matter of potential customers having a greater amount of knowledge about what the different options are, and unfortunately there's just not a lot of information out there apart from the promotional information that each company has. So it's very good to see this sort of forum occurring, where people are actually given a bit more information about what teams go on.

JENKINS: Perhaps Ed, Neil, or Dave you guys could also speak to this issue of whether there should be concessionaires, or whether it's even possible.

VIESTURS: I would agree with Guy. To go into another country and tell them they need to start regulating would be very difficult first of all, and then to figure out who would be sitting on a committee and what their knowledge is of what's actually going on would be very hard as well.

We couldn't send our own committee over there and then start picking and choosing, you know, who gets to go and who doesn't get to go. I would agree as well that it's going to be up to the people to choose and also hopefully that more legitimate people are actually operating trips on the mountain. And maybe, eventually, it'll just sort itself out.

People will see that if this kind of thing continues on year after year, people are going to hopefully get it that ultimately, you do get what you pay for. And if you do have a problem on the mountain, “if I'm paying extra, I will have people with me that can help me not only to get up but to get down safely.”

It's just gonna have to be a kind of “Buyer Beware” kind of a thing. And if that doesn't happen, this kind of stuff is going to keep repeating itself, and it has repeated itself year after year. But, as Guy said, this year for some reason the media has kind of woken up and said: “Hey, what's going on on Everest?” And we've seen this kind of stuff going on repeatedly.

BIEDLEMAN: Ed, I have to disagree with one thing that you say there. And that is that people are going to figure this out. I think that's true that some people will figure this out, and those are the people that you're going to want on your trip and they're gonna be successful in the terms that we've talked about here. But, there's always going to be people who come on these trips who think they know better, think they can do it cheaper, think that they can get involved and figure it out themselves the first time, and I just think that that element is never going to go away.

VIESTURS: Right, that's what I meant. I meant to say that I would hope that people would figure it out, but like I said, I don't think they will because things like this are going to repeat themselves and we can't really-other than educating them help figure it out for them. We've gotta let them know, “here's what you're getting for what you paid for,” but I agree with you that some people won't get it.

BIEDLEMAN: Right but the problem-in addition, not a contradiction, but in addition to that [is that ] as the guiding services, you guys get better and better and understand the mountain more and make it safer for your customers and provide more margin and good services. As the guides get better and guide services get better and you guys figure it out so it's safer, more margin and you understand the mountain more that's fantastic, and that's good for your customers and you guys. But on the mountain as you know, the higher you go, eventually everyone condenses and there's this confluence where all the other people who are more strung out and don't have the margins, intersect paths and that's always going to be there when you have such diversity of abilities and competence on the mountain, And that puts everyone at risk.

HAHN: I would just point out that you can treat crowds and inexperienced climbers in somewhat the way you treat poor weather and poor route conditions and rockfall and icefall potential you know, you can have your radar up, and if crowding conditions are looming, that's a good enough reason to call off a summit bid or postpone one.

BIEDLEMAN: Absolutely Dave, but as Ed and Guy know, during our situation in '96, those guys went back up on the mountain. thTy weren't even there in that place Ed's radar was up and Ed put himself along with some other folks in a very dangerous position to help members out that were up there,. I know you've done the same and would do the same so you could be safe and sound back in your basecamp tent. Something unfolds and the call to action comes, you're gonna go for it. And that's again putting yourself in harm's way there.

HAHN: You bet, and as with you I don't have a lot of faith in climbers and would-be climbers to always sort that out ahead of time, but I guess I have even less faith in a government entity to

BIEDLEMAN: Oh yeah, I totally agree and I'm not saying these things thinking that they could be regulated. Maybe in a perfect world, if it were all of a sudden regulated, maybe there would be some benefit to that. But ten years ago maybe it's changed but ten years ago just going into the Ministry of Tourism and trying to get your permit was an unbelievable process-browning papers stacked up the ceiling, being blown around by ceiling fans. I can't even imagine how they would tackle regulation responsibly and effectively. And then in the end, somehow westernerss would get what they needed or what they wanted there and the people of Nepal would probably feel that their mountain had been hijacked by someone else. So I think that the regulation process they don't even have a government right now, so I can't imagine how they would regulate something like this.

JENKINS: Well how about this then, guys? Question five is: does it seem to be possible at least the way you guys are describing it should clients, prospective clients, prospective Everest climbers, have some kind of competency test? Now this would probably come down to the individual guiding services, would it not?

COTTER: Absolutely, and I mean it was proved again this year that anybody who doesn't get on one of the guided expeditions just goes shopping. And what ends up happening is they end up getting on one of these expeditions being run by a Nepalese trekking agency that has no requirement apart from the ability to pay. And no back-up once they get these people people who are quite often not going to make it onto a commercial team because of a lack of experience they're going to find themselves on Everest. And then what happens is that these commercial teams that have turned these people down often have to rescue them these same people who they've turned down from joining their team. So they get rescued without paying anything to the guiding company that's doing the rescuing.

JENKINS: Not to mention the danger that they put the guides and Sherpas in, correct?

COTTER: Absolutely. So therefore, we don't like to see it, but you're going to have that same thing of the people who really need to do a competency test for their clients are the ones who are least likely to.

HAHN: And we talked again about who it would be-like the possibilities, do you invite the UIAGM in? (The International Federation of Mountain Guides Associations, the regulating body for guides in much of the rest of the world) and I'd say well, no, I'd rather that not happen.

The UIAGM doesn't have particular experience in guiding the highest mountains, so I wouldn't really want to see a body like that trying to tell us what to up there. And yeah, as somebody who works in heavily-regulated parks like Mt. McKinley, yeah that's a whole lot of government presence on the mountain, it's bad enough in the ministry of tourism! [Laughs] But on the mountain, you know, ON the mountain, that's a lot of government in those parks.

JENKINS: So you guys are saying in effect, that in the better guiding services on Everest, they are already doing these competency screening for clients?

GROUP: “You bet.” “Very much so”

COTTER: And it's personality testing as well. Obviously we want to try and avoid wingnuts as much as possible. So we are always screening people and a big part of what we do as a responsible guiding company is actually help people achieve a standard they need to get to before going to Everest. So often, our clients we've known for years before they've even come to the mountain. We've taken them on other expeditions, we've trained them up and gotten them ready.

Actually, a reasonable proportion of our business is preparation for people to get to Everest. Because we want people to succeed, we want people to come on expeditions and be successful as much as possible. We've alluded to it a little bit before, but what we'd like to see is staking the odds in the favor of the client and in the expedition as a whole to succeed, so therefore the whole process of getting people to the mountain is a long one for us.

JENKINS: Is that true guys, with you and Ed and Dave? That you find that many of your clients kind of do work their way up, at least partly through this mountaineering apprenticeship before they come to Everest?

VIESTURS: Oh for sure. The people that we believe take on Everest for the most part (whatever company that they go with) they quite often have been on other trips with that same company. They know the guides, and the guides know them.

As Guy said, these people kind of come up through the ranks they don't just get up off the couch and say: “I'm going to go to Everest.” That's not the kind of people that Guy would accept on one of his trips.

The client pool is quite small and once they attach themselves and work with a certain guide organization and if things go well, they'll continue to work with that same organization and with that same guide. So everyone kind of gets to know each other and by the time they do have the qualifications and do sign up to go to Everest, quite often there is some cohesiveness within that team. And here again, you're going to get a better outcome. It's going to be safer, it's going to be more enjoyable and the people within that organization and within that team are probably going to help each other more than the cheaper teams.

So again, you get what you pay for. You're paying more, but the quality and the safety and the chances of success, of walking away and getting home, like Guy said, is what you're gonna get out of that. And that's what you have to try to convey to people when they're shopping around. And the ones that don't get it won't ever get it.

JENKINS: Let's go straight to Sherpas, because this seems to be intimately connected to what you're talking about-some of the Nepalese trekking agencies on Everest and perhaps not having the skills. Right now we're seeing that Sherpas are being trained to become guides, and I'd like to know what's happening on that front. Do we have at this present time wholly-owned and operated Sherpa guiding services for Everest? And are they capable and competent at this stage? I'm sure at some point they will be. Where does that stand right now?

COTTER: Go Dave

HAHN: No, I was actually going to suggest that you tackle that. (laughter)

COTTER: Ok, well I think that there are actually two questions here. One is the Sherpas being guides, the other is the Sherpa companies. I'll address the Sherpas becoming guides because this is something that's moving along. The Nepalese mountaineering association is certainly trying to push for Sherpas to get more training and for them to be more involved on their own as guides, which I think is fantastic.

All this takes time. It takes [time in] any country to become involved in the International Federation of Mountain Guides (or UAIGM) and for the Nepalese it takes even longer for the difficulties of language and culture, etc.

But Sherpas are naturally fantastic guides. They're great at looking after people, they're very attentive to people's needs, they're wonderful people in general and so that will make them great guides in the future once they get their training. However, there's a lot to be done with them from a technical standpoint, and now there is some training being undertaken in Nepal, just for Sherpas to learn proper technique, which is great to see and I think that's having a positive effect.

As far as them learning first aid, avalanche awareness skills, rescue skills, I think it's still a long way off before the majority of them are going to be capable of anything technical in those areas. But there are a few who have actually become internationally qualified mountain guides by traveling to Europe and such places. So it's actually starting to happen, and that's a great thing.

But there's also the Sherpa companies which are running some of these expeditions and which are owned by Sherpas, and I think that they are really interested in profit, first and foremost. What's surprised me with everything that's gone down on Everest this year is how some of these Nepalese trekking agencies that have been running these expeditions a lot of the stuff has been going wrong for several years haven't been getting any flak whatsoever. If it was one of us guiding, one of us western guiding companies, we'd be taken to the ring of by the media, but for some reason they don't want to go there with these Nepalese trekking agencies. But I think that some of it will probably game more scrutiny over time.

JENKINS: Let me ask you quickly, one of these companies is Asian Trekking, and I certainly want Dave or Ed or Neil to jump in as well, but it does seem as if some of these companies are operating on the cheap, and I'm wondering whether there is some at least anecdotal correlation between companies that have inexperienced or no guides, or simply Sherpas who are untrained in search and rescue and the correlation between that and risk and subsequently (or inevitably) death on the mountain.

VIESTURS: You know, I think the reasons that some of these services are actually able to operate is that there are people that are looking for that level of service. Or they think that that's the only level of service that they need. A lot of these people think that they have enough experience that they don't need a guide to climb Everest. They just want someone to organize and run the trip so they can go off and climb the mountain.

A lot of those people that do sign up have definitely overestimate their abilities and in the end they underestimate what the mountain can do. A lot of those people and a lot of those groups, they get in trouble. And then it's the people running the higher-end trips with the experience and the strength that have to come to their rescue.

So it's supply and demand. These people are operating companies because there are people who are looking for that level of service. And it's hard to get rid of that.

HAHN: And getting back to what has to happen before Sherpas can be fully or responsibly involved in guiding over there, is the build-up of skills that we're seeing. But there's also what I see as two main obstacles.

Economics, I think, become more of a factor for Sherpas. We talked about the pressure on western guides that guiding rich clients brings out, but it's amplified, really amplified when you're combining that with Sherpas who are economically (as far as Nepal goes) doing very well, but there's still a huge gap between them and a wealthy westerner. That can create extra pressure, so I think that's one big obstacle.

The other obstacle that I worry about is that somebody might use the help of a Sherpa, might hire a Sherpa and use everything that that Sherpa has to offer until that Sherpa says, “hey, I don't feel good about this. I don't trust the weather anymore, we're not doing well enough, time to go down.” Then I have this fear that then it reverts to “you're just kinda carrying my stuff, and I'm making the big decisions here, so I'm going on to the top.” That they'll take what the Sherpa has to offer in terms of strength and everything, but then they don't quite have the stature yet well, as we all like to think we have the ability to turn somebody around by having ultimate authority up there.

BIEDLEMAN: Yup, that's a very good point Dave. And even in '96, I felt that a little bit as a western third guide myself. It's hard to get to the point where you can command that authority and use it appropriately, because the consequences on either end are big at times.

I think that we're talking a lot about clients, or customers that definitely need guiding. I think there's another group of people who deserve some place or some means to get onto the mountain and maybe get some help with permitting and things like that and those are people who are experienced climbers who maybe want to go and try Everest on their own and maybe the only thing they don't want to deal with is getting the permit. Maybe some of these types of expeditions are right for them. Usually they will take care of themselves very well and will understand what it is what they're getting from these services, and then not get their expectations above that and then take care of themselves very well.

But I think it's important that we keep in mind that there are lots of other people, and some who are very competent and capable of climbing Everest and making good decisions, and we need to make sure they have a place and a means to get there and do it themselves.

HAHN: You don't usually hear about them so much afterwards.

BIEDLEMAN: No, you don't because they do it right, whether they're successful or not, they usually keep themselves out of trouble pretty well and manage their teams well, but that's sort of the nature that comes to that sort of team knowing themselves and each other kind of early on.

JENKINS: Neil, I'm glad you brought that up because that was one of my questions, and you've kind of answered it. And that is, that the model that you're describing is the model that I went to Everest on, on the North Face in '86. And that is a group of climbers who know each other, who have climbed together that was a group of us, Carlos Bueller and Todd Bibler and Annie Whitehouse, and we put together a team and we had a guy.Basically, we were a climbing team.

We didn't succeed, but we all came home and we were still friends and we all had our fingers and toes. And it seems like there is still room for that, by going with one of these cheaper outfits, although from what I've heard and I know from people who have tried this that the north col route and the south col route are so crowded during the spring season that it can be difficult. There is a fixed line. Do you want to use that the whole time? And also many of the tent platforms are used can anybody address that?

VIESTURS: I think you're correct, when you go as a team that you just described. Unfortunately you're just going to be confronted by all these other groups that's just the nature of Everest today there's so many people there, it's not the “wilderness experience” that you might've expected 15 years ago where you were the only expedition there.

So, if you do choose to go there, on one of the more popular routes, whether it's the north col or the south col, that's what you're going to be deal with. There's going to be a lot of people and there's going to be fixed ropes and whether you choose to use those or not or walk ten feet to one side to say that you were more “independent,” well, that's something that you're going to have to figure out.

Certainly the other options are to climb one of the other routes that aren't popular obviously they're going to be more difficult. Or, sadly to say, just go somewhere else.

JENKINS: Or climb in a different season I suppose.

VIESTURS: Well yeah, but then you're chances of success are reduced and the margins of safety are reduced. If you're going to pick and choose to go to Everest, you're going to want to maximize your chances and typically that means going in the spring. We've seen a lot of teams that go in the autumn, and now they have permits for the monsoon, but your chances are pretty slim of succeeding.

JENKINS: Thanks guys. Let's move on, I don't you to feel like your on the phone forever. As mountaineering has matured it's also, like all other sports, become more litigious, particularly here in the U.S. as well as in England.

We have cases now where people come back from Everest expeditions and they're suing their guide, for whatever reason. I'm wondering if this becomes particularly poignant when someone may have died or somebody who may not have been rescued who should have been rescued.

We have several scenarios that have happened this year and last year that I'm sure you're all aware of. So, I'm wondering, should Everest climbers be signing documents that say, “Look it, when it's between you summiting, and the team trying to save someone someone's life, as part of the team or someone else, that takes precedent.” Would that make any sense and would it even be effective at high altitude?

HAHN: I think that is already a part of any reputable trip over there. Those discussions happen, and that's already going on. But this is may be the other half to what we were saying earlier. You were asking whether we thought we could responsibly guide on Everest and whether we could rescue people, and I think we said that we did feel we could. But, there are certainly situations where we all know that we can't save people above the south summit or in some places on the north ridge if they can't walk then no, they also can't be carried on some of that terrain.

The reason I bring that up now is that that's another very obvious discussion that has to be had on responsible expeditions before you go up there, before you sign on. The limits of guiding, and sometimes the guiding relationships that I've entered into over there, it's not just having the person's whose signing up, the one who is doing the climbing, read and sign off on all the paperwork. It's also his or her spouse to do the same so that they understand. We all know plenty of situations where the climber knew firmly in his mind what the risks were and what he was undertaking, but yeah it's the people who are left behind that may have the vast misunderstanding.

JENKINS: So, once again the onus kind of falls upon the guiding services to help your client through an earlier apprenticeship to understand the very mortal risks of mountaineering at any level, and then explain what it really means to be on Everest and how dangerous it can be. Does that sound right?

Ok, we're doing great here guys. I'm sure you are all familiar with this among mountaineers and alpinists and certainly the hard-core, Everest has sort of lost its cache. Because of so much negative media attention, it's become as much an icon for greed, ambition and incompetency. I mean these are antithetical to the mountaineering ethic I think they are for you guys as well. I want to first ask, if this sentiment (that Everest has nothing to do with mountaineering anymore, or climbing) is this sentiment actually accurate to what you guys have actually seen on Everest?

COTTER: I would like to say that, to a point, it is accurate. High-altitude mountaineering, to be good at it, you have to be an expert in the art of selfishness. And mountaineering, when you're climbing with a partner, the two of you, you just deal with your own issues. You help each other out when you need to but you do your bit as best you can, your partner does their bit as best they can, that's mountaineering and that's part of the beauty of mountaineering.

But that's very different up on Everest for a whole bunch of reasons, but part of it is that you're running into all these other teams and having to deal with other groups in addition to your own. It's all well and good having this ethos of mountaineering that people think about, but it's a bit different when you come across a team of people with a completely different culture that are part of some big national group and you don't like the way they do things anyway, and then you find out you've got to rescue them, they're idiots then you've got to confront a few things that you might not have to in any other form of mountaineering.

I also think that the opposite is coming out of it, we're just not hearing it. One of the things I took away from '96 was how amazing it was that all these teams who all had the ambition to get to the summit all dropped everything and went to try and rescue climbers who were lost and out there and frostbitten and need help. It was amazing watching that happen.

JENKINS: Guy, is that still happening? I mean, all you guys give me a sense hear. We generally hear about Everest when things go wrong. But there are many many expeditions there every year and I'm assuming many things go right with many of them. I know with my climbing personally, you don't say much. You do your trip and come home. You may actually have done rescues on your trip, and again, if that works out, you don't say much about it. Is that what's happening on Everest?

COTTER: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, it's happening all the time. There's a lot of very positive things going on.

I think that as far as all of us commercial operators, the communication is way better than what it used to be. We're doing a lot to actually avoid accidents, we're all getting together to work on the mountain and all these little teams who never did anything to help anyone in past, they're still not, and were not even asking them to.

We're just making up for it, because we want things done right. I think there's a lot of good stuff going on that we haven't been very good about telling everybody about as an industry, if you like, because we want to get on with our own thing, we don't want to comment on what other people are doing or how we've helped other people out too much. We just get on with it.

HAHN: Yeah I would agree. I see lots of good things going on. I see people helping each other all the time. A specific case this year, when a Czech climber fell on the Lhotse face and was near death before anybody even knew he'd had an accident. They discovered him the next morning. I saw great stuff a Chilean team going out of their way, putting themselves at risk to get to this climber, get him back on the route. It was clear to almost everybody that he was going to die, but they took the time and effort I think it was right up by the yellow band on the Lhotse face right by 25,000 feet, getting close to that, and again, this man had suffered some very serious injuries and had been out all night, unbeknownst to anybody, so everybody witnessing this knew he was going to die.

It was sad, but this Chilean team that hoped to summit Lhotse the next day,When you get the kinda thing hanging over your head you don't want to waste energy, you don't want to use up energy. You want to get into your high camp early and prepare. But no, these guys the leader of the team, their doctor they changed their plan. They enlisted the help of all the Sherpas that were up there to move this climber. The Chilean doctor stayed with him until he died and put his own summit plans back a day. He decided to stay down at camp 3 for that day.

JENKINS: Dave, Ed, all you guys, is this a common occurrence? The kind of thing we don't hear about that we should be?

HAHN: Yeah, people do the right thing up there they often do. It seems to be the popular media story that people are kooks, and in my experience, yeah there are some kooks out there, but by and large there are some pretty good folks and they do help each other and I'd say that's the norm. And yeah there are going to be some cases where people are unable or do not help each other for whatever reason, but I'd say more often, it's one of the reasons I like being there. There are good people and good things happening.

VIESTURS: I agree with Dave. And it's the good things that happen that the media really isn't interested in. They want controversy, they want conflict. They want to talk about the things that are going wrong.

It's quite often the things that are going well. The people that do the right thing don't go around and toot their horn and say “here, look at what we just did.” They just feel that that's their moral obligation, that's the right thing to do and if something happens they go and do it. And quite often as well it's the people that get rescued or barely, barely get away with something they don't want to admit it either so it very rarely comes out.

I think there's a lot of (more often than not) close calls on the mountain but you never hear about it. People don't want to admit the problems that they had: “Hey I got to the summit, but by the way I'm not gonna tell you that somebody dragged me on the way down.” I'm not gonna want to admit that, and you never really hear about that.

JENKINS: Guy, I think that you had similar sentiments to what Dave said, about the fact that you are frequently involved in rescues and they often work out successfully, but there's nothing ever written about them.

COTTER: Umm, no, absolutely. I mean I can't really elaborate on that much. What these guys are saying is absolutely right. And part of it is that we haven't been very good at promoting that side of things. We do dispatches from the mountain, we send out a little bit of information but yeah, we certainly don't jump up and down about it.

What was interesting this year on the mountain was that we did a couple of dispatches about a dog that came up on the mountain, up to the bottom of the Lhotse face. And we actually got more feedback from people about that, and more concerned people writing about the dog than anything else that we've ever had.

JENKINS: A man's best friend is not a man![Laughter]

JENKINS: If some of the negative aspects about Everest particularly it seems you guys are talking about people who are inexperienced and also inexperienced enough to believe that they can go cheap and then get themselves in trouble are there ways to change the Everest experience for the positive? One thing that we've already brought up that I thought deserves a little more attention is the possibility of limiting numbers on Everest. This happens of course throughout the U.S. in backcountry areas. Could this happen on Everest, and would it make a positive difference?

HAHN: I'll take a stab: Yeah, definitely limit the numbers as long as you let me in. [Laughs]

JENKINS: And that's what everyone's thinking, right?

HAHN: Exactly. And that's when you love it in an American part, when you're one of the few that are let in to one of these areas. But I don't think it's gonna happen. I don't think it's realistic. Again, we're talking about the Chinese/Tibetan government and we're talking about the Nepal government and yeah, personally I don't believe it's a practical idea because I don't think either of them are going to limit that.

VIESTURS: For them, selling permits is a commodity and for us to come in and say listen, we want you to sell less of those, who are we to go in and tell them how to do that. And as Dave said as well, yes as soon as you start regulating, yeah the people who happened to get permits, they're the lucky dogs, and then you have all the other people and other operators that are kind of banking on the fact that they can get a permit. And when they don't, they're going to run out of business and that's the way it used to be in the past. We were all stomping and screaming and like, “Hey give more permits! We really really want to go.” And now the floodgates are opening and open and everybody is happy but we're also suffering some of the consequences of all the people that are going on the mountain.

BIEDLEMAN: Then the supply and demand issue comes in. If you were to regulate it somehow, the cost goes up because it's such demand, and going to Everest becomes something only a few people can afford and you cut out all the folks that are just everyday, normal climbers as well. I guess if there was some kind of regulation that allowed different types of groups in, I guess that would work, but I don't know how that would be regulated or how you could even possibly write something like that.

JENKINS: I think what you're all saying-and it's also what I've experienced with many trips to Asia-is that the complications with regulation, whether it's numbers or whether it's peak fees, is very very difficult, and probably not feasible. Is that what I'm hearing?

VIESTURS: Yeah, I would tend to agree with that. Especially in a foreign country. Here in the U.S., where things are very well-organized, we're able to set up committees and regulations but to go somewhere else and ask other governments to do what we think is true and what we think is right is kind of hard to do and hard to assume that we have the right to go and do that.

HAHN: I think we've hit on a little bit of an irony here. In '96 it seemed like what was part of the public surprise was that Everest had, in their eyes become a domain of the wealthy. And maybe in reaction to that, here we are ten years later, and no, you don't have to be wealthy to go to Everest. People can go for less than the cost of a car. There are plenty of not-wealthy people on Everest, and I was saying before

COTTER: The guides

HAHN: What? Ohhh yeah! [Laughs] Plenty! But I was saying before, I didn't want to be around someone who wanted to save money on Everest, I meant that as far as someone who wanted to save money and save time and not put in the years but there are plenty doing it on the cheap that I respect, that are doing it well. Yeah, I wouldn't want to see something get in the way of that. I wouldn't want to see the bar put so high financially by a permit system that it was out of reach.