ON THE NORTHERN COAST of the Philippine island of Jolo lies a small resort, some 30 bamboo-and-thatch huts stretching a quarter-mile along a white-sand beach overlooking the tropical Sulu Sea. People spend their days here kicking back in hammocks, spearfishing along the coral reef, or simply watching fruit bats sail between the coconut trees.

Jolo, Philippines

While most operations are civil-affaris efforts, the troops still head into Abu Sayyaf-held jungle on combat raids.

While most operations are civil-affaris efforts, the troops still head into Abu Sayyaf-held jungle on combat raids.Jolo, Philippines

Filipino Brigadier General Juancho Sabban at his headquarters near Jolo City

Filipino Brigadier General Juancho Sabban at his headquarters near Jolo CityJolo, Philippines

Ex–Abu Sayyaf, some of whom now serve as guides

Ex–Abu Sayyaf, some of whom now serve as guidesJolo, Philippines

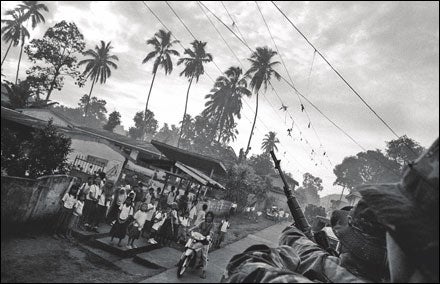

The village of Pansul

The village of PansulNobody ventures very far from the resort. It’s paradise, after all, plus there’s the fact that the whole place is ringed with concertina wire anchored by sandbagged gun emplacements, and that you might be killed if you were to go anywhere else on the island without an armed escort. The Beach Resort, as it’s called, is officially known as Buhanginan Base, home to 125 Filipino marines and 12 American Green Berets, part of a joint Philippine-American task force formed after 9/11 to take down a terrorist group called Abu Sayyaf. The troops’ mission was to contain the outfit, a onetime jihadist faction responsible for a string of Western tourist kidnappings from high-end resorts in Malaysia and the Philippines but it was much more ambitious than that. Even before the fall of the Taliban at the end of 2001, the lawless jungles of the southern Philippines had emerged as the biggest terrorist base outside Central Asia. The ultimate goal was to prevent another Afghanistan to deny that sanctuary to fleeing Al Qaeda operatives and regional groups like Indonesia’s Jemaah Islamiya, the outfit later believed to be responsible for the 2002 and 2005 Bali bombings and those of the J.W. Marriott Hotel and the Australian embassy in Jakarta in 2003 and 2004.

By 2006, after four straight years of operations, the joint troops had sustained an estimated 100 Filipino and 11 American dead. And they’d contained Abu Sayyaf predominantly to a single island, its historical stronghold of Jolo. Geographically isolated, blanketed by jungle, and run by an obscenely corrupt government, Jolo (pronounced HO-lo) is a terrorist sanctuary par excellence. Its half-million inhabitants are like many Abu Sayyaf members of the Tausug tribe: desperately poor, Muslim in a country of Roman Catholics, and linguistically separated from the rest of the Philippines. But ever since a charismatic Filipino brigadier general named Juancho Sabban took command in April 2005, the joint forces were actually succeeding in winning over the Islamic people of Jolo. Using a classic “hearts and minds” strategy of about 85 percent civil-affairs projects and 15 percent combat operations, they’d turned this 345-square-mile island into the one theater in the war on terrorism where the momentum seemed to be moving in America’s direction.

“We think there is a model here that’s worth showcasing,” Major General David Fridovich, the Hawaii-based U.S. Special Operations commander in the Pacific, told reporters last spring. “There’s another way of doing business.”

Last July, I moved into a tiny hut at the Beach Resort. Jolo was unlike any war zone I had ever been in. In many ways Buhanginan Base reminded me of a tropical frat house, albeit one with its own 81mm mortar pit and an inordinately high level of scar tissue. The Filipinos and Americans often hung out, shooting hoops or mangling eighties power ballads on their guitars. Nights were, if possible, even mellower. Dinners featured whatever creature the cook could get his hands on: wild boar, goat, bonefish, a python. After the meal, we’d gather in the officers’ wardroom, a thatched hut swathed in mosquito netting, to drink brandy cut with wild ginseng and watch a heinous Philippine soap called Majika, which chronicled the tragic love triangle between two spandex-clad witches and a swinging warlock. It was must-see TV for the Filipinos and Green Berets, who used the commercial breaks to fine-tune operational plans.

���ϳԹ��� the perimeter, the scene was a bit different. Poverty seeped into every pore and up the nose. Every few hundred yards along the coastal road (the island’s only paved thoroughfare) stood small clusters of huts on stilts, constructed of bamboo, tin, and salvage by refugees from the interior who’d fled the fighting. There was no means of private transport save a precious few bicycles and dirt bikes. Families bathed and washed their clothes in water holes the color of Yoo-hoo. Yet Jolo’s is a gun culture, and many households owned an assault rifle, if very little else. During lunar eclipses and New Year’s, the sky above the capital, Jolo City, looks like the first night of Operation Desert Storm over Baghdad as folks unload flaming rivers of phosphorous-coated ordnance into the heavens to chase off evil spirits.

I spent my first week on the island accompanying the marines and Green Berets to schools and medical clinics. The picture I got was certainly of a terrorist group on the defensive, but to what degree it was hard to know. Then, one night as we were watching Majika, a Filipino major named Jimmy Larida called me over to his table. Larida was a sweet-natured operations officer built like a floor safe; I’d been hounding him for days to take me out on something sexier than a book drop. I found him sitting alone before a large operations map.

“Here,” he said, pulling out a chair. “I want to show you something.”

It was the plan for the next morning’s mission, an innocuous-sounding operation called the Upper Tanum Water Source Site Survey. Supposedly, in a hilly patch of jungle called the Tripod, there was a 50-year-old concrete cistern that collected water from a spring that was also Abu Sayyaf’s main water source. The marines intended to construct a water system off the cistern to supply about 3,000 villagers downstream, people who had long supported the Muslim insurgents. Sabban wanted to flip their loyalties.

We were taking a spigot?

With a heaviness worthy of Staff Sergeant Barnes in Platoon, Larida described past encounters with Abu Sayyaf in the Tripod, units decimated and corpses mutilated in a jungle death trap of interlocking bunkers, booby traps, and spider holes. With well over a hundred killed or wounded out there in the past three years, the marines always went into the Tripod in large numbers, or at the very least at night. But this time, an undermanned company was going in at midmorning, lightly armed, with no artillery or air support. He handed me a black leather pouch.

“My .45,” Larida said. “Take it tomorrow.”

Was he kidding? It was hard to imagine being blown to pieces on the set of a Corona ad.

“If we get overrun by Abu Sayyaf,” he warned, only half joking, “I put two clips in there, 14 bullets. Save the last one for yourself.”

“Come on,” I said.

“You’re American,” he said gravely, all but channeling Tom Berenger. “They’ll skin you alive.”

IT SEEMED A BIT THEATRICAL, but there was no reason not to take Larida at his word. Abu Sayyaf wasn’t as strong as it had once been, but it could still muster enough fighters to overwhelm 84 lightly armed men. More apropos, if five years of recent history proved anything, it was that Abu Sayyaf and Americans made a bloody mix.

The group became notorious at the turn of the millennium, target=ing tourists in the southern Philippines and East Malaysia. In 2000, Abu Sayyaf abducted 21 tourists and employees from a dive resort on Sipadan Island, releasing 20 of them months later for up to $25 million in reported ransom. On May 27, 2001, the group struck again. Three slight, camouflaged men bearing M16s burst into the beach cabin of Martin and Gracia Burnham, an American missionary couple celebrating their anniversary at the Dos Palmas Arreceffi, an exclusive resort just off the Philippine island of Palawan. The men forced the half-dressed couple onto the deck of a 35-foot speedboat and, after nabbing another American and 17 Filipinos, vanished into the Sulu Sea. Six days later they took four hospital workers, and two weeks after that they beheaded three of the hostages: a cook from the Dos Palmas, a security guard, and the third American, 40-year-old Californian Guillermo Sobero.

The Burnham kidnapping was picked up by news outlets, thanks to its tantalizing mix of vacationing Americans, sea pirates, and island paradise, but nowhere was Abu Sayyaf portrayed even remotely as a threat to national security. When it was first formed, in 1990 by Abdurajak Janjalani, a Filipino mujahedeen veteran who’d fought the Soviets in Afghanistan, Abu Sayyaf (Arabic for “Father of the Sword”) was dedicated to fighting for a strict Islamic state in the southern Philippines. It was reportedly funded by Osama bin Laden’s brother-in-law Mohammed Jamal Khalifa and trained by such veteran Al Qaeda leaders as Ramzi Yousef, the architect of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing.

According to U.S. intelligence, Abu Sayyaf remained a serious jihadist threat throughout the late 1990s, even after the death of Janjalani in 1998. I got a different picture from seven ex Abu Sayyaf I interviewed on Jolo, including the group’s former imam. After Janjalani’s death, Abu Sayyaf had devolved into a criminal enterprise, they told me, with ransom windfalls going directly to his more secular-minded successors, Abu Sabaya and “Commander Robot.” While Sabaya and other leaders spoke of jihad in public, the imam said, in private their aims were decidedly more temporal.

In November 2001, President Bush announced that the U.S. would send troops and aid to the Philippines, opening what the media came to call the “second front” in his war on terrorism. By spring 2002, Exercise Balikatan was in full force, with 660 U.S. Marines, Green Berets, and Navy SEALs acting in an advisory role, as the Philippine constitution forbids foreign combat operations on its soil joining the CIA and FBI personnel already in the southern islands. Using bugged cell phones, spy planes, double agents, and even a takeout pizza tracked by a drone armed with an infrared camera, the CIA took upwards of four months to locate the Burnhams and the remaining hostage, a Filipina nurse the others having either been killed, freed, or ransomed. In the ensuing firefight between Abu Sabaya’s forces and the Philippine army, Gracia Burnham was rescued; her husband, Martin, and the nurse died in the crossfire.

Up until about a year before I arrived, maneuvers on Jolo consisted largely of combat raids, with the Americans remaining on base while the Filipinos conducted battalion-size search-and-destroy sweeps backed by helicopter gunships and artillery batteries. The United States supplied Special Forces advisers, signals intelligence, and logistical support via the U.S. Joint Special Operations Task Force Philippines (JSOTF-P), while the Filipinos provided the manpower and local knowledge. By mid-2003, a good number of Abu Sayyaf’s core leaders were in prison or the grave.

But it was precisely during this low ebb that Abu Sayyaf was reborn on Jolo as a true international terrorist threat. With its leadership solidified under Khadafi Janjalani, the staunchly jihadist younger brother of the deceased founder, the group formed an alliance with Jemaah Islamiya, which had been all but forced out of Indonesia after the first Bali bombings. Using Jolo as their base, the terrorist partners struck back, launching new attacks, training operatives in scuba diving, and planning raids on resorts in Malaysia. In 2004, Jemaah Islamiya and Abu Sayyaf, working with a third, Manila-based group, sank the multistory SuperFerry 14 as it left Manila Bay, killing 116 Filipinos. It was the deadliest terrorist attack in Philippine history.

THE MOOD WAS APPREHENSIVE on the morning of the Upper Tanum water mission, as 77 Filipino marines and seven U.S. Green Berets assembled at the Beach Resort. The Filipinos wore rosary beads and ‘do rags with their Vietnam-era jungle fatigues and soup-bowl helmets; many carried ancient M14 rifles or 35-year-old M60 machine guns. Decked out in Kevlar and armed with ergonomically engineered and optically enhanced weaponry, the Americans looked like a lost squad of stormtroopers from Star Wars.

The last two times the marines had ventured into the Tripod, in December 2005 and March 2006, they’d killed approximately ten Abu Sayyaf, but at the cost of two soldiers and another 13 wounded. Many of the marines gathered today were veterans of those battles, though it would be the first visit to the area for the Green Berets. Major Larida addressed the troops. “I would like to tell everyone that the creek we are now going to see the water is sometimes mixed with blood. Sometimes mixed with blood of Abu Sayyaf, sometimes marine blood,” he said, his voice quivering a bit. “So if a firefight starts, everyone down on that creek will be a sitting duck. So today security will have to be to the very highest degree.”

Weapons were locked and loaded, bullets clanking into their chambers. The marines pushed out a muted “Oooooooooorah,” then piled into the backs of their rusted old personnel carriers and Korean War era jeeps. The Americans climbed into their armored V-150s.

We lumbered down the coast road, past several jeepneys overflowing with passengers and an old man riding a water buffalo, and through two marine checkpoints to Tanum, a chain of hamlets that stretched two miles up into the foothills. A stronghold of Abu Sayyaf, Tanum had once been home to Ramzi Yousef, and, as recently as five months earlier, a 40-man marine detachment stationed here was harassed nearly every evening by snipers. Now Tanum’s leadership, many onetime collaborators themselves, had volunteered to lead the task force into the heart of Abu Sayyaf’s regional base camp.

Our convoy halted long enough to pick up ten local guides. The oldest, a fifty-something man wearing a 1963 Vermont Lacrosse Lions T-shirt and carrying a 12-inch blade, climbed into the jeep next to me. Sinewy as a suspension cable, he introduced himself in remarkably good English as the chief of the village of Tanum. His constituents, he said, had petitioned him to ask the marines for a water system after seeing the benefits accruing to other villages cooperating with Sabban’s men.

“But why is the Abu Sayyaf letting us do this?” I asked.

“I send one person up there other day to go find Abu Sayyaf,” he said. “Tell them the military is helping us with water project. I ask, ‘Please no problem?’ Then I receive message from them. It said, ‘We will go away from your municipal.’ “

“But why do they go away?”

“What can they do?”

“Attack us? Destroy the water system?”

“No,” he said, with a sly grin. “They know if they destroy water project, the people will hate them.”

We turned onto a muddy track, rumbling past a cinder-block mosque strangled by vines and an old schoolhouse pockmarked with shrapnel wounds. The convoy finally ground to a halt about three miles inland as the track funneled into a narrow footpath beneath an archway of coffee and coconut trees. It was humid, the air still. When the engines shut down, I heard parrots squawking.

A marine recon platoon of 26 men went first, led by several Tanum guides. Minutes later, the main body followed, only for Major Larida to halt it about 200 yards in. His radioman had passed him a message: Eighteen Abu Sayyaf had been seen a mile east of the cistern, heading our way.

Larida’s fear here was a pantakasi, a Tausug “cockfight derby.” Pantakasi occurs when men in a given vicinity with weaponry pretty much any male over 11 on Jolo are called out to swarm and annihilate a pinned-down enemy. Eighteen Abu Sayyaf could quickly multiply into a few hundred men firing M16s and swinging swords, as Larida had seen himself the previous November. He summoned one of the Tanum guides, a wild-looking young man in a baseball cap and black hair extensions who I later learned was an undercover Philippine intelligence officer. The marines began taking cover while the head Green Beret, a hulking captain from small-town Massachusetts, ordered his men to spread out. Larida finally made contact with his recon platoon, who’d just secured the hilltop above the cistern. All was quiet, they told him.

There were signs of Abu Sayyaf everywhere: a camouflaged observation post, empty packs of Astro cigarettes and Cloud Nine candy bars (both Abu Sayyaf favorites), a flip-flop, and fresh footprints. “Shit, they were just here,” a Green Beret whispered, as he fingered newly cut banana leaves on the observation post.

We had liberated the cistern. There it was, built into a sheer hillside: two cast-iron spigots sticking out of a cement box a little bigger than a VW bus. The guides rushed over. One said something to a marine. He shrugged. Another laughed. A Green Beret guesstimated flow rates, while another eyeballed the gradient of the slope and two more filmed the scene for the intel guys back at the Beach Resort. Despite any historical, religious, or cultural differences, it was pretty clear that the Green Berets, Filipino marines, and Tausug villagers all agreed that this was one damn good water source.

An odd war here, I thought. The allies just ran a major military operation deep into enemy-held jungle and without a shot took a lousy piece of concrete that anywhere else wouldn’t even garner graffiti. It wasn’t exactly like storming the Normandy beaches, but then again that was the whole point. It wasn’t just that the Green Berets and marines were winning the civilians’ loyalty; it was that they were forcing the enemy to collaborate in its own defeat.

WINNING THE “HEARTS AND MINDS” of a civilian populace is an age-old strategy: Chinese military philosopher Sun Tzu preached it in the fifth century b.c.; Mao mastered it; the U.S. tried it in Vietnam and is once again returning to it in Iraq and Afghanistan. But for an occupying force, as the Americans and Filipinos arguably are on Jolo, this strategy is especially tricky.

No one has a defter touch at counterinsurgency than Juancho Sabban. Now 49, the Filipino general has a quick smile and a legendary resolve hidden beneath a soft foam build. He is both a marine’s marine and a congenital maverick: a family man (his son just graduated from high school in New Jersey) and decorated combat veteran who also helped overthrow dictator Ferdinand Marcos in 1986 and tried to topple his successor, Corazon Aquino, in 1989. Sabban was arrested for rebellion and mutiny, sawed his way out of a maximum-security prison with a smuggled hacksaw, and lived in the rebel underground for two years. He was granted amnesty in 1995.

A key practitioner of what the U.S. military now calls the Basilan model, Sabban first employed his version of hearts-and-minds against Islamic separatists on Palawan in 1983 and honed it fighting Abu Sayyaf on the island of Basilan in the late 1990s and again in 2002 as part of a similar U.S.-Philippine initiative. The day he took over on Jolo, he ordered his men into a hut for a PowerPoint presentation. The first slide quoted Sun Tzu: “The acme of skill of the true warrior is to be victorious without fighting.” The second showed his standing order: “Behave!”

Under the command of Sabban and his American counterpart, Mindanao Island based JSOTF-P leader Colonel James Linder, the forces drove the remaining 500 or so Abu Sayyaf fighters into the interior highlands and set about winning over the Tausug populace along the coast. (���ϳԹ���‘s request to interview Colonel Linder was denied, and he was rotated out of Mindanao last fall, replaced by U.S. Army Colonel David Maxwell.) One of the Green Berets summed up the efforts: “They were small projects in resources but ones with a big impact on the people’s lives. That’s the key to this counterinsurgency not for us to keep going to them with solutions but to somehow get these people to come to the marines for help.”

As I learned on Jolo, the campaign was noble in principle and often hilarious in practice. Traveling with a minimum force of 20 Filipino marines and several Green Berets, we would speed back and forth on Jolo’s paved road like a platoon of armed elves, delivering chairs to cheering schoolkids and visiting adult learning centers. One particularly sweat-drenched day, we headed out to an isolated hamlet called Sitio Lavnay for the turnover of a new well, one that would bring clean drinking water to 125 desperately poor families. The heavily guarded ceremony featured local VIPs in little plastic chairs, several roaming chickens, and 100 villagers gathered in the stifling heat. It opened with an acoustic version of Dire Straits’ “Money for Nothing,” blasted into the jungle on a boom box, and only got worse.

After the Muzak overture, the speeches started. A lean, clean-shaven Green Beret admonished the villagers to “take ownership of the resource,” while the marine-battalion commander thanked the dignitaries for their hard work. Unfortunately the speeches were delivered in English and translated into Tagalog, a language the assembled Tausug couldn’t really understand. During the ribbon cutting, a mongrel dog drew the event to a close by taking a leak on the podium.

But for all the ham-fisted production value, the villagers still lined up patiently to thank the soldiers. The most important event that day went little noticed. After the ceremony, the chief, a handsome man in black jeans, slipped a Filipino officer a single sheet of paper with a carefully typed list of needs. It was exactly the kind of act Sabban’s counterinsurgency doctrine was designed to elicit.

He was winning without fighting.

SOON AFTER THE ASSAULT on the cistern, I accompanied Sabban on a civil-affairs mission to the seaside village of Pansul. We rode in his beat-up Toyota Land Cruiser, sandwiched between a six-by-six truck loaded with marines and a monstrous vehicle that looked like a steel hippo with an anti-aircraft gun bolted onto its back. There were several plainclothes security officers darting around on Japanese dirt bikes, and an advance unit had already swept the road for mines. Sabban’s was probably the most valuable head on the island.

With the truck’s air thick with pine freshener and the seats slick with Armor All, Sabban talked about the war. They’d turned the tide, he felt, but all the same the progress was tenuous at best.

“As a young lieutenant,” he told me, “I discovered you get better intelligence when you are with the people. And when I was a rebel and on the run in 1990, the authorities can’t catch me if I have supporters. Who else will get the best intelligence but the civilians themselves? If they don’t want to tell on the enemy, even if area is size of basketball court, you will not find the enemy.”

Sabban pursued graduate studies at the Naval War College, in Rhode Island, so he’s thought about this a lot. “People know you are more powerful than them,” he said. “You don’t have to rub it in, but when you go down to their level, adopt their ways, they will take you in. The more you hurt them, the more they fight back. Even if they are inferior, they will find a way to get you.”

Changing minds takes cash. The U.S. embassy in Manila estimates that, between 2002 and 2006, the American aid agency USAID spent $4 million a year in Sulu province. In the Jolo area, the embassy reports, the U.S.-Philippine forces have completed more than 50 development projects roads, classrooms, wells valued at $4.5 million since 2003. This includes projects with big PR value, like the eight-day visit of the U.S. Navy hospital ship Mercy last June, but, say some troops on the island, fewer behind-the-scenes, long-term initiatives.

“I’m sometimes afraid all this stuff about Jolo being the ‘new model to win the war on terror’ is PR bullshit,” an American soldier familiar with the operations on Jolo had told me, requesting anonymity because he was not authorized to speak with the media. “The money goes everywhere but where it’s going to do the most good.”

According to Sabban, the JSOTF-P has provided around $50,000 in in-kind donations to the projects he has personally directed in the last year. His largest donor, he maintains, is not the American government, not the Philippine government, not the World Bank, but a private citizen named Andy de Rossi, a slightly manic Italian expat engineer and businessman living in Manila. Through his personal aid group, the Promotion of Peace and Prosperity Foundation, de Rossi has to date given $600,000 worth of in-kind donations, his own little mini Marshall Plan. He has also donated $850,000 in development aid for Jolo in partnership with the U.S. government and the JSOTF-P, including shipping used ambulances from the United States via the U.S. Navy. (“Already, with basically nothing, we’ve performed miracles down there,” he told me in Manila.) After de Rossi, Sabban’s most generous supporters are a small network of relatively wealthy Tausug elites, whom he’d invited today to Pansul. As we drove along, I asked Sabban what he needed the Americans for. Although he deeply appreciated the U.S. efforts on Jolo, he said, he wasn’t exactly diplomatic, either.

“I don’t need the Americans here to train my men. I don’t need them here to fight,” he said. “I need the Americans here because I hope they can provide strategic investment. Because to keep the momentum moving in our favor, we are soon going to need to fund not just schoolbooks and chairs but large projects, expensive projects.”

“How much to do all of Jolo, get the place up and running?” I asked.

He thought for a few seconds. “Two, maybe three million,” he said. “That would do a lot.”

At midmorning we pulled into a heavily secured pasture, near an idyllic stretch of beach, where the marines and Green Berets were running a free veterinary and medical clinic. Tied to coconut trees were 30 or so malnourished cows and an equal number of hard-luck goats. A row of Tausug men squatted on their haunches and smoked butts while a Green Beret veterinarian, wielding a hypodermic needle the size of a caulk gun, wrestled a moaning cow against a fence. An American medic took a little girl’s blood pressure; another U.S. officer handed out posters of the USDA’s food pyramid in English.

The Tausug elite were gathered around a picnic table at the far end of the field. In addition to a marine colonel and the well-regarded local chief of Buhanginan, there were five others. One was a woman named Hadja Nur Ana “Lady Ann” Sahidulla, although most people call her simply the Princess, as her clan traces its lineage back to Jolo’s old royal family. Recently elected vice governor of Sulu province, the Princess is dark-haired, petite, and cosmetically pale; besides her involvement in politics, she’s also a local rock star (she was performing in a few days at a party for Sabban) and a gun enthusiast. The Princess’s entourage included a stylist, an effeminate young man bearing a parasol, and a bodyguard with a pearl-handled .45 strapped to his leg. She herself was dressed in a T-shirt and jeans: Sabban had only recently convinced her that, when intermingling with commoners, it was perhaps wise not to wear her traditional princess attire of flowing silks and jewels.

Also at the table was an old man in leather boots and tight jeans who’d ridden up on a 250cc Suzuki dirt bike. This was the sultan of Patikul, a quasi-religious figure among the Islamic Tausug. When he perspired, a young woman patted down his brow with a pink kerchief. The sultan was pursuing an ambitious plan to develop a half-mile of Sulu Sea beachfront into a first-class resort, a no-brainer but for the fact that Jolo was still a war zone. Finally, there was the sultan’s son, a twig with a ponytail and the personal warmth of a chained cobra. Like the Princess’s, his business dealings were veiled.

This was Sabban’s donor pool: a handful of extras from The Rocky Horror Picture Show. But the general, ever respectful, began his pitch. In total, the Upper Tanum diversion would cost $10,000. He explained how many villagers would benefit and how it would help push Abu Sayyaf farther into the hinterlands. He tried to convince them that they had a financial stake in its success. As he spoke, a subtle ballet began around the table. The Princess’s parasol bearer slipped a portable electric fan in front of her. Luxuriating in the artificial breeze, she acted as if she couldn’t hear a word Sabban was saying. The sultan feigned interest, but his son took offense at some undetectable slight. He pirouetted and, with his back to us, held his hand up, as if he were on Jerry Springer. In the end the only people listening were the marine and the chief of Buhanginan, the only two at the table without money.

A FEW DAYS BEFORE I left the island, I went out on a night ambush with ten Filipino recon commandos. We were to stake out a jungle path that Philippine intelligence believed might be used that night by an assassination team led by a high-level Abu Sayyaf named Abu Solaiman, who had recently been put on the FBI’s Most Wanted Terrorists list for his involvement in the Burnham kidnapping.

Armed with rifles and a single night-vision scope, our team headed out on foot a few hours after nightfall. ���ϳԹ��� the glow of the base, it was pitch dark, so I blindly followed sounds made by the commando in front of me. We trekked for about two miles, slipping into a patchwork of cassava fields, through tended coconut groves and jungle, and under a sprawling canopy of string beans before squatting for 20 minutes in what smelled like a garden of rotting cabbage. I cupped my hands over a map as our team leader, a staff sergeant from Luzon, checked, rechecked, and triple-checked it with a penlight. Around 11, we finally settled into our ambush position astride the path in thick bush, just off a stretch of the coastal road known as the Boulevard of Death, where hundreds of Philippine Army soldiers died in rebel ambushes in the 1970s.

“Now we wait for them to come to us,” the staff sergeant whispered, holding up the scope.

We sat. Even though it was a clear night and there was a sliver of moon, it was impossible to see anything. There was constant buzzing around my ears, and insects were flying up my nostrils. A lone gunshot sounded a ways off, but otherwise it was like spending eight hours in a black Hefty bag full of mosquitoes.

We returned to the base just before dawn. Sabban was in the wardroom, drinking Nescafé while Seinfeld played on TV. He was an early riser, usually enjoying a morning run with an iPod loaded with love songs. As we chatted, a man, quite tall and neatly dressed in a golf shirt and khakis, walked in. He was Erich Q. Tan, a city councilman from Jolo City, the fetid capital, where the streets are lined with sewers and hit squads of young Abu Sayyaf on dirt bikes prowl for target=s. In the weeks before I arrived, they’d killed four marines and several civilians.

Tan wanted Sabban to revamp Jolo City’s overwhelmed sewer system. This would be by far Sabban’s most expensive project to date, costing upwards of $250,000, way beyond the reach of the usual suspects. The only institution Sabban figured would cut such a check was the American JSOTF-P. After helping the councilman with a project application, he stuck in his own letter of recommendation. The process, he said, usually took months.

From the other end of the table I asked what the chances were that the project would get approved. Sabban shrugged. Tan shrugged. Neither seemed very optimistic.

“You know Richard Gere?” Sabban suddenly asked. I’d told him I’d met with the philanthropic actor once. “If I wrote him a letter, you think he’d read it?”

“Probably,” I answered.

With this the city councilman smiled and clapped his hands together, suddenly rallied.

Ever the warrior, Sabban called for a pen and paper.